Gay Pride Activist, 10, Is ‘Our Future,’ Say LGBT Fans

June is Gay Pride Month, and for Desmond Napoles — a boldly out 10-year-old who became a viral sensation in 2015 after strutting for hours in a rainbow tutu as a part of New York City’s Pride March — that means a full schedule.

“We have our future,” drag queen Crystal Demure said by way of introducing the lanky blond boy to a tender-hearted crowd on June 12 in Manhattan’s West Village, where masses had gathered to mark the one-year anniversary of Orlando’s Pulse nightclub massacre. Desmond took to the stage, alongside legendary drag queen Rollerena. He was there for a task that felt heavy beyond his years: to read some of the victims’ names.

“Jerald Arthur Wright… Amanda Alva… Darryl Roman Burt II,” he read quietly, dressed in mourning drag of a beaded black crepe dress and black flowered hairnet. The crowd embraced Desmond, as the LGBT community does wherever he goes.

“For gay men of a certain age, many of us weren’t able to come out until we were at least 18… if not in our 30s or 40s,” event organizer Jay Walker, of the group Gays Against Guns (GAG), explained to Yahoo Beauty at the memorial. “So the fact that the world has changed in such a way that this child can know himself so fully, and that his parents can support him so fully that he can be fearlessly out, is a huge, huge thing to most gay people, regardless of gender.”

That was beautifully apparent just a week earlier, when Desmond (who is officially 10 as of June 23rd) brought some precocious-child realness to the NYC Legacy Ball in Brooklyn, slaying the crowd from the runway in a Keith Haring-inspired ensemble. And then there was Brooklyn Pride, just days before the Pulse memorial, when the pint-sized inspiration could not take 10 steps through the street festival in his native borough without being stopped by adoring fans.

“Desmond!” called out many gay, lesbian, and transgender grownups, a fair share of them men in tutus similar to the one that Desmond wore, along with light-up high-tops and a fuchsia sheath dress, for the occasion.

Receiving nearly as much adoration from folks in the crowd were Desmond’s parents — admired by adults who wish they’d had the same support when they were LGBT children themselves.

“For me, the most emotional part is that his father brought him to the [Legacy Ball], and to see he’s embracing his individuality in such an amazing way,” explains one middle-aged man who posed for a selfie with Desmond during the Brooklyn festival. “I wish I’d had a father like that — and family — who was not making fun of me if I started dancing… but would embrace or encourage me. It’s beautiful.”

Adds Desmond’s mom, Wendy, in between helping her son apply bright-red lipstick and encouraging him to pose for adoring photographers, “A lot of times it’s just people expressing that they wish they could’ve had a childhood like that, and could’ve been as free. They’re really inspired because things are changing, and it gives them some hope. He’s like a symbol of the future, that things are getting better.”

Both of Desmond’s parents — Wendy, a currently unemployed human resources manager who was close to a gay uncle who died of AIDS in 1994, and Andrew, who works for a software company — say they were raised in nonreligious, open-minded families and that it wasn’t such a leap for them to come to terms with their son’s emerging orientation. “He came out in kindergarten,” says Andrew. “He went into school identifying as gay.”

The more difficult parts of the family equation, they say, have been the following: managing the critical and often hurtful reactions of strangers (“People who feel that they have the right to somehow judge how we live or how I parent,” says Wendy); seeing Desmond’s reactions as he discovers the suffering of LGBT people throughout history — something he’s insisted upon learning about, mainly through intense AIDS-related documentaries such as How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger; and the further complication of dealing with the fact that Desmond has Asperger’s and ADD.

“That’s far more challenging than [his being gay],” says Andrew, who also has Asperger’s. “He was bouncing off of walls, and though we tried not do, we had to medicate him in kindergarten, because it was just too much.”

Then there’s this surprising fact: Even though it’s 2017 and they live in New York City, the family has been unable to find specific, formal support for families of gay children — only those for gay adolescents or teens, or children who identify as transgender.

“If he were a transgender child, then there would be more support,” says Wendy, who has been plugged into PFLAG and other groups, including the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, which welcomed Desmond into its Brooklyn Pride contingent for the recent march. But, his mom adds, “he was really adamant that he didn’t want to be a girl, he just wanted to dress in drag.”

And, as Andrew adds, “that was by the time he was 6 years old.”

They supported his desire and took him to drag shows and the annual Pride events, and then, after waiting a year longer than Desmond had wanted, they allowed him to join the 2015 NYC Pride March, when he was just 8 years old. While media images from that day drew plenty of harsh critics — including Rush Limbaugh — it inspired much praise, too, particularly from the LGBT world, which, Andrew said, has just “grabbed him and sucked him in.”

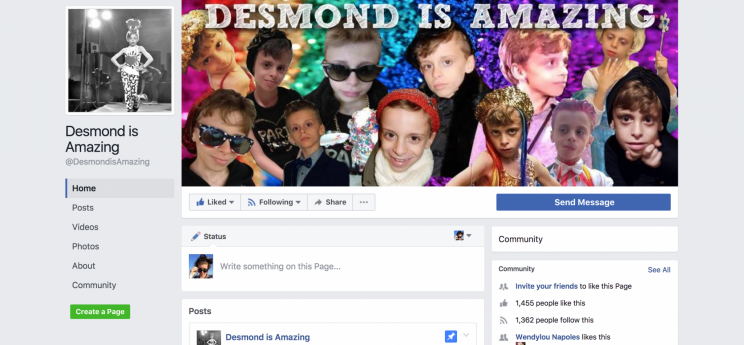

His son, whose public appearances now get catalogued by Wendy on an official “Desmond Is Amazing” Facebook page that was started by a family friend, has loved every minute of it.

“It felt good, because now everyone’s watching my videos,” he says. “[It makes me feel] very noticeable and good.” Desmond explains that he deflects any criticism he might feel coming from his peers by being funny, noting, “I just make everyone laugh at school, because I make jokes.”

Still, the lack of family support, on a larger level, has been troubling, Wendy explains. “I think it’s an old-fashioned idea, but it’s like, ‘Well, until they hit puberty,’ and ‘How do they know for sure?’ [Gay children] is kind of a taboo subject, I guess… People will say, ‘Oh, he’s been oversexualized’ or ‘He shouldn’t know about sex,’ when it has nothing to do with it. It’s his identity.”

The fact that Desmond’s parents understand that basic concept is extremely important when it comes to his well-being, explains Caitlyn Ryan, director of the Family Acceptance Project at San Francisco State University, who says that children will typically self-identify as gay as young as 6 years old and that the average age of having a first crush, gay or straight, is 10.

“In studies as early as from the 1970s, you will find adults speaking in retrospect, saying, ‘I knew when I was 5,’” Ryan tells Yahoo Beauty. But that reality has somehow not yet fully translated into modern-day awareness.

“I think people think everything’s just fine for gay youth and only an issue for adolescents,” she says. And she confirms that, in addition to there being a real lack of disseminated facts about gay youth, services for LGBT youth are surprisingly hard to find — mainly because, historically, parents were viewed as being a rejecting presence rather than a supportive one.

“From the beginning, families were not seen as part of the solution,” Ryan explains, noting that the main thrust of LGBT youth support, historically, has been protecting young people from harm, rather than a wellness approach. “And so adjusting to families being supportive is a huge task, as people are still thinking of it as a phenomenon.”

Ryan is a clinical social worker with 40 years of experience working with the LGBT community, and her research-based materials and assessment tools have focused on improving the health and well-being of LGBT children and their families since founding the project with Rafael Diaz in 2002.

She expounds on this idea in a recent piece for the Temple Political & Civil Rights Law Review, “Generating a Revolution in Prevention, Wellness & Care for LGBT Children and Youth,” noting that a sweeping change is needed when it comes to the approach to LGBT youth support. “Perceptions of family reactions drove the way that services developed and evolved within LGBT youth support programs and mainstream health and mental health services. Providers saw part of their role in rendering services and care as protecting LGBT youth from harm, which included protecting them from their parents and families.”

One way to change the perception of what LGBT kids need in the way of support, Ryan says, is to focus, through education and health services, on the fact that “sexual orientation is part of normative childhood development.” Instead, she says, it’s too often “relegated to sexual behavior. It’s not about sex, it’s about relationships and really seeing who you are and people like you. It’s about human relationships — which can be social, emotional, spiritual, as well as romantic and sexual.”

Which is, luckily, how Desmond’s parents understand his identity. “There are more children like this, but they’re not out and not in the media,” Ryan says. Although there has been a slow but steady flow of books geared toward kids like Desmond — including the newly released Sparkle Boy picture book, by LGBT children’s book pioneer Lesléa Newman, children need more. “Until we take seriously that it’s a normal part of development,” she notes, “it won’t be incorporated in services, training, or education.” There will also continue to be a lack of more informal support, such as playgroups or support groups.

Regarding Wendy’s belief that her son would have more support if he were transgender, Ryan says that’s likely the case. “A large point is that providers just discovered gender diversity in children recently, so that’s become an emerging field of practice. At the same point,” she says, “there hasn’t been an awareness among people that kids identify as gay at around 6 and up.”

Desmond and his family, for their part, are doing everything they can to help raise that awareness. And that goes for people of every age, whether they are kids looking for role models, parents looking for others going through the same thing, or gay or lesbian adults who see this 10-year-old as a beacon of hope.

“It represents a sea change in the way that LGBT kids grow up,” says activist Jay Walker. “It’s everything to us.”

Read more from Yahoo Beauty + Style:

The Boy Scouts Banned an 8-Year-Old Transgender Boy — Is This Discrimination?

Perez Hilton’s Mom Is the Best Thing on His Instagram Account

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Pinterest for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day. For Twitter updates, follow @YahooStyle and@YahooBeauty