She Was Raped for Working at an Abortion Clinic

The guy wanted to know if she worked at an abortion clinic.

On their first date, a day or two earlier, she’d told him she worked in “women’s health.” Now, he was texting her about specifics. She answered yes and asked if that was a problem. He said no.

But from the start of their second date, she knew something was wrong.

“He acted really weird the whole time,” Calla Hales said. “Really standoffish. Closed off. Downright rude at times.”

About halfway through the meal, when he got up to go to the bathroom, Hales asked for the check. Her date got angry but still asked her to go home with him. When she declined, he walked her to her parking spot, and as she was getting into her car, she says, he came up behind her, pulled her into the backseat, and raped her.

“He had me in between the seats, wrapped the seat belt around my neck, and at some point, bit me on my chest,” Hales said. “He said things like I should have expected this and that I deserved it. He asked how I could live with myself and said I should repent. That I was a jezebel. That I was a murderer. That he was doing no worse to me than I had done to women. He said he would make me remember him.”

After about 15 minutes, a noise spooked her attacker and he left. Terrified and stunned, Hales drove to her friends’ house and showed them the bruises. They wanted to call the police, but Hales said no, she wanted to get herself together and go home. She went back to work the next day.

“I worked all weekend and didn’t say anything to anybody,” Hales said. “But the whole time I was bleeding.”

Hales is the director of A Preferred Women’s Health Center (APWHC), which operates four abortion clinics across North Carolina and Georgia. At 27, she oversees a staff of 60 and the administration of the clinics, which collectively provide care for more than 20,000 patients a year. Her mother and stepfather opened the first APWHC in Raleigh in 1998, when Hales was 8. Her mother was the director of the clinics and her stepfather was the doctor. Like her three older sisters, Hales began working in the Raleigh clinic as soon as she was old enough to be helpful. After getting a bachelor’s degree and MBA at Hofstra University in New York, she moved back and became the communication and budget coordinator before taking over the director role in January 2017.

“What my parents did has always been in the air, and we never thought it was weird or frowned upon,” Hales said. “But growing up, my parents were always telling us to be careful who we talked to and mindful of what we said.”

Hales was schooled on how to answer the phone and what to say when asked what their parents did. Both parents own bulletproof vests, as does Hales, and have a license to carry.

“I’m a gun-toting Democrat,” her mother said from her perch on the desk in the clinic’s front office, her 40-caliber handgun tucked away in her purse. “It’s always scary because you never know what’s going to happen and, oh my god, I have always worried about my daughters’ safety. We are always a target.”

Ever since the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade in 1973 that women have a constitutional right to an abortion, extreme opponents of abortion have subjected providers and patients to disruption, harassment, and violence, including murder, arson, and bombings. Clinics have had acid poured through their mail slots and received anthrax through the mail. In its 2016 report, the National Abortion Federation (NAF), which monitors clinic harassment and violence, found that picketing, vandalism, obstruction, invasion, trespassing, burglary, stalking, assault and battery, and bomb threats are all on the rise. Clinics reported 60,000 incidents of picketing that year, an all-time high since the NAF began tracking these statistics in 1977. The report also documented a five-fold increase in hate speech and internet harassment, which escalated after the election. The 2016 National Clinic Violence Survey, published by the Feminist Majority Foundation, found that the percentage of clinics reporting the most severe types of anti-abortion violence and threats of violence has dramatically increased from the first six months of 2014 to the first six months of 2016 - from 19.7 percent to 34.2 percent. Hales was raped in November 2015.

Now abortion rights advocates fear the violence and harassment may get even worse. The Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act, passed in 1994, made it a federal crime to use force, threat of force, or physical obstruction to interfere with a person’s right to obtain or provide reproductive health services, but it’s only effective if enforced.

“Sometimes I get the sense that the police officers here are just winding down the clock,” said Alixandra Taylor, who volunteers as a clinic escort at APWHC in Charlotte. “Like it’s not going to be an issue for much longer, so why uphold the law now? Clearly no one has said that to me, but when things are getting heightened and the officers are leaning up against their cars on their phones, it's a pretty clear indication.”

Attorney General Jeff Sessions has a legacy of voting against measures that would protect clinics and abortion opponents have expressed delight over his appointment. Vicki Saporta, president and CEO of NAF, says she is concerned that the current Department of Justice will not enforce laws that protect abortion clinics with the same vigor as previous administrations and this will take pressure off local law enforcement. Without that layer of accountability, threats and violence will continue to escalate.

“Trump has encouraged people to express their basest emotions and to threaten people - he has given the anti-abortion movement license to increase their vitriol, if not their criminal activities,” Saporta said. “We've seen time and time again that if anti-abortion extremists are allowed to get away with lower-level criminal activities, those escalate into [extreme violence].”

On the Monday after the rape, Hales went to a Planned Parenthood. They gave her a blood test but recommended she go to an emergency room for stitches. Hales went to a hospital where she was least likely to encounter someone who knew her or her family, but, she says, the nurses told her to come back the next day to be evaluated by an ob-gyn to determine if she needed stitches. When she returned, the hospital staff had no record of her previous visit.

“When they couldn’t find me in the system, I opened the paperwork they gave me the day before and realized it was for a 56-year-old man with angina,” Hales said. “Finally I was like, ‘Fuck it. I don’t care about anonymity anymore. I need to get seen.’”

At UNC Medical Center, Hales received a series of blood tests, took prophylactic antibiotics, and went through the process of completing a SANE (Sexual Assault Nurse Examiner) report that documented her physical injuries. She decided to file a blind, or anonymous, report with the Raleigh Police Department.

“I did not want to press charges for a few reasons,” Hales says. “The idea of retribution on my parents, my friends, my business, and my staff. I didn't know if I could survive the mental and emotional trauma of a court case at the time. There also was, and still is, a large amount of embarrassment and misplaced guilt - feeling like I should have done something to fight back, like I should have worn different clothes, that I missed a warning sign.”

The next morning, after calling her parents to tell them what happened, Hales went to the clinic where she worked.

“It was a conscious choice to not do anything different,” Hales said. “I think I thought that if everything was normal, it would be OK.”

Within weeks, though, Hales began to see her attacker’s face in the crowd of protesters outside the Raleigh clinic. At first, she thought she was being paranoid. But then, she says, the protesters began to yell things they hadn’t yelled before, echoing words said to her during the assault.

“The protesters outside started calling me a jezebel a lot more,” Hales said. “And I got letters in the mail saying that I deserved it.”

They also said things they could have known only from talking to her attacker or seeing her rape kit. Hales has a tattoo of a serotonin molecule on her left rib and one day, a protester asked what molecule her tattoo was of.

Hales received a barrage of anonymous text messages, phone calls, and voicemails. She’d pick up the phone and hear someone breathing heavily. She’d get voicemails that said, “Do you remember it?” Some days, she received hundreds of blank text messages. One night while at dinner with friends, she got a text from an unknown number that said, “That shirt looks pretty on you.”

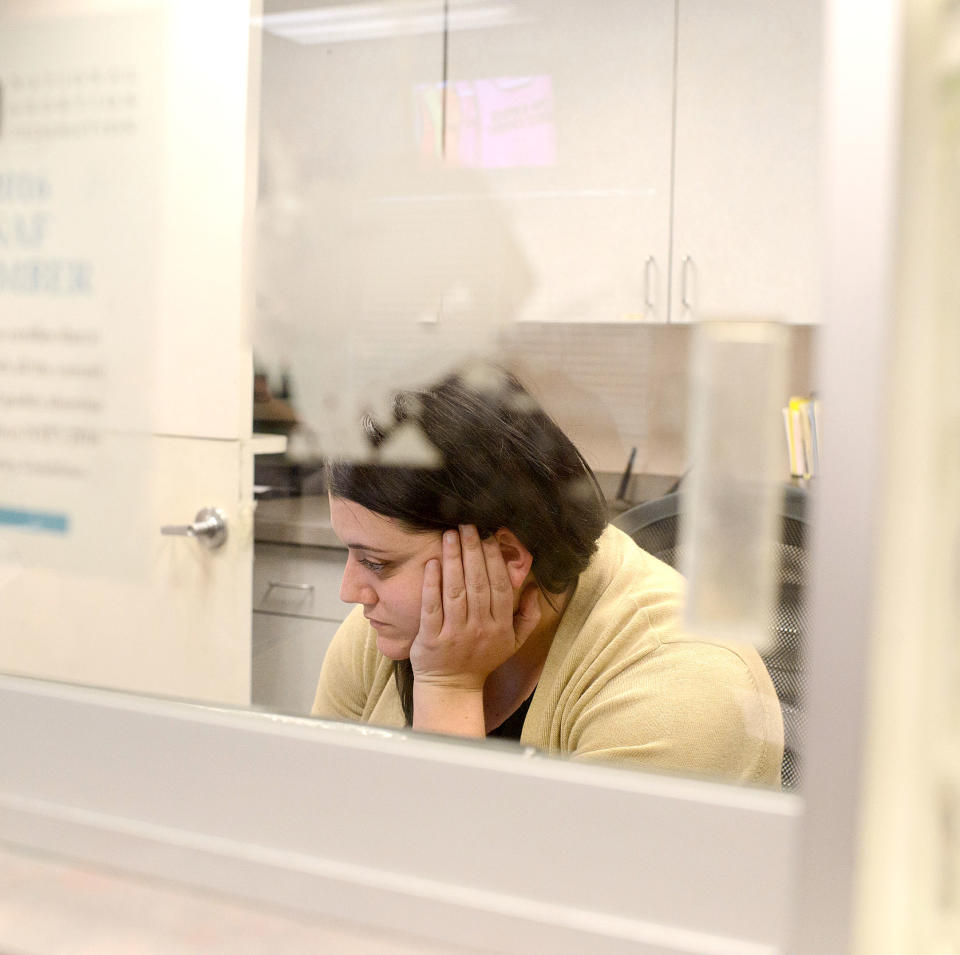

“I lost it,” Hales said. “I had a layer of panic everywhere I went. I’d get to the clinic at 6 in the morning and not leave until 4 p.m. I wouldn’t walk outside. I’d refuse to leave until I knew there were no protesters.”

In early January 2016, Hales left her own birthday party early because she thought she saw her attacker in the crowd. She was feeling increasingly fearful, paranoid, and alone, so she picked up and moved to Charlotte. It’s where the APWHC’s main office is located – and 170 miles away from the man who sexually assaulted her because she worked at an abortion clinic.

The protests at the Charlotte clinic are among the most intense in the country.

On a recent May morning, about 150 demonstrators had gathered outside by 10 a.m. A clinic volunteer had gotten into a yelling match with protesters who were leaning on her car and Hales walked past the police barricade to talk to the cops.

“They murder innocent babies in there,” a man yelled, his voice amplified by a speaker system.

On the other side of the road, a swarm of people in matching teal T-shirts raised their hands in supplication toward the sky as another man with a microphone expounded on the evil unfurling inside the brick building. A cluster of children near the front of the group clutched baby dolls. Another group waved gruesome signs that purported to show images of aborted fetuses and approached every car that drove up with pamphlets. Down the road, a group of Catholics bowed their heads in prayer.

After a short conversation with one of the officers, Hales returned to her office.

“So this is Saturday,” she said wryly. Saturdays are the biggest protest days at the clinic, and crowds, microphones, grisly signs, ultrasound buses, praying, and shouting have become the norm.

More recently, on June 10, a group called Love Life Charlotte called for 1,000 men to join them at their Men for Life prayer walk at the clinic. “The truth is that this is more of a man’s issue than it is a woman’s issue,” founder Justin Reeder said in a video posted on the organization’s website.

The regular protests are nothing new. In the early 2000s, Operation Rescue, a group known for blockading entrances to clinics during the 1980s and early 1990s, moved to Concord, North Carolina, about a 40-minute drive from Charlotte. One of the leaders was the Rev. Philip L. “Flip” Benham, and when internal feuding split Operation Rescue in two, Benham became the head of his faction, Operation Save America - still one of the most extreme anti-abortion groups in the country. In 2011, Benham was found guilty of stalking after following abortion doctors to their homes and creating “WANTED” posters with their names and home addresses. A judge ordered a new trial on appeal due to a procedural error but the district attorney ultimately dropped the charges.

In 2010, Benham’s sons founded Cities4Life, a group that deploys protesters outside the Charlotte clinic six days a week. Daniel Parks, the director of Cities4Life, says he’s been there every Saturday for the past 12 years and his wife, Courtney, a registered nurse, mans one of the two “mobile ultrasound” buses outside the clinic. “We know that we can’t force anyone to do anything,” Daniel Parks says. “If a mom goes on the mobile unit and still decides to go through with an abortion, all we can do is pray for her.”

Another group, Reformation Charlotte, is not only there to protest abortion, but also to try to convert the Catholics. “There are people out here from all walks of life who we believe are dying in their sin and it's not just people that are going here to have abortions,” Jeff Maples, Reformation Charlotte’s director, told me when I visited. “There are Roman Catholics over there who are pro-life but don’t believe the gospel.”

Protesters told me their goal is to help women, but according to the office manager of the Charlotte clinic, their presence can be harrowing.

“We see it a lot on patients' surveys, about how mad the protesters are, about how they yell slurs,” she says. “We just had a patient get called a ‘filthy whore.’ The protesters say things about doctors too and that gets the patients scared.”

Hales, meanwhile, moved from Raleigh to feel safer but entered an environment that is even more virulent.

“It’s like trading one evil for another,” Hales said.

A year and a half after the attack, Hales avoids crowds when she can and changes her appearance (sweats one day, a dress another; contacts one day, glasses another), so she is not easily recognizable. She lives in a secure apartment building, but even though one of the local anti-abortion groups posted her address online, she says she’s more concerned about potential harm to her cats than to herself.

Hales said it’s hard to tell whether the protests have gotten worse since Trump was elected because the protest climate around APWHC in Charlotte was already so hostile, and city officials and law enforcement already didn’t provide much in the way of support. However, like one of the clinic volunteers, she has a sense that the people standing outside the clinic feel emboldened, as if it’s just a matter of time before legal abortion is gone for good. Hales is also concerned about how policies - like the Republican health care plan and new state abortion restrictions - could affect her patients, the clinics, and people, like her, who have been sexually assaulted.

The silver lining to the election, she says, is the clinic has seen an outpouring of support from local supporters of reproductive rights. The number of people volunteering as clinic escorts and defenders has surged since November, providing a critical support system that helps patients get into the clinic safely.

If anything, the rancor of the protesters has strengthened Hales’s resolve. “There is a certain level of therapy in doing it,” she said of her work at the clinic. “I wanted to prove that I could because it’s like an angry ‘fuck you’ to the people outside.”

That Saturday, she wore a black Planned Parenthood T-shirt with the words “Wicked Jezebel Feminist” scrawled across the front, a nod to the words used to describe her during and after the attack.

“They haven’t kept me from doing my job and from wanting to be a human,” Hales said. “The best thing I can do to prove them wrong is to continue to live and be a loudmouth. I mean, what could happen that’s worse than what’s already happened?”

Follow Rebecca on Twitter.

You Might Also Like