21 Showrunners in Three Seasons: How ‘Happy Endings’ Became a Case Study on the Value of a Traditional Writers Room

ABC’s ratings-challenged Happy Endings created a cult following thanks to its relatable stories about a group of friends in their late 20s and early 30s. While the comedy helped to launch the careers of stars Eliza Coupe (Jane), Elisha Cuthbert (Alex), Zachary Knighton (Dave), Adam Pally (Max), Damon Wayans Jr. (Brad) and Casey Wilson (Penny), behind the scenes, the Sony-produced series created by David Caspe was effectively its own showrunner training program. As Rutherford Falls creator Sierra Teller Ornelas revealed in a recent Twitter thread, Happy Endings had 23 writers over its three seasons, with an incredible 21 — including assistants — becoming showrunners.

During this week’s TV’s Top 5 podcast, hosts Lesley Goldberg and Daniel Fienberg reunite 14 of the Happy Endings writers to build off Ornelas’ thread and discuss, in light of the ongoing Writers Guild strike, the benefits of having a traditional writers rooms, why having writers on set is an invaluable on-the-job training ground and how mini-rooms are bad for television.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

Anonymous Strike Diary: The 'Well-Known Creator' Can't Get AI to Write a Decent Protest Sign

Writers Strike Collateral Damage: Janitor Layoffs at Studios Spur Demonstration

Joining TV’s Top 5 this week are Happy Endings creator-showrunner David Caspe (Black Monday), showrunner Jonathan Groff (Black-ish), showrunner Josh Bycel (Solar Opposites), Sierra Teller Ornelas (Rutherford Falls), Prentice Penny (Insecure), Lon Zimmet (Night Court), Dan Rubin (Night Court), brothers Daniel and Matthew Libman (Champaign, ILL), Jackie Clarke (Blockbuster), Amy Aniobi (Insecure), Leila Strachan (Night Court), Hilary Winston (Krapopolis) and Jason Berger (The Big Show).

What follows is an edited version of the sprawling reunion. For the full conversation, listen to this week’s TV’s Top 5 (below).

Sierra, your May 9 Twitter thread inspired this reunion. In your thread, you noted there were 17 writers on season one of the show, seven of them staff writers including you, and that it was dubbed “America’s Next Top Staff Writer.” One of the key issues the Writers Guild is striking for is minimum room size. Why is the WGA fighting for room-size guarantees and the end of the so-called mini-room?

ORNELAS Even though it was Caspe’s first job in TV, and it was my first job in TV, there were a slew of people who had [been on shows] a bunch and were excited to tell us how to do it. Through that process of doing 22 episodes, by the end of it, you knew how to produce an episode of television. As I moved up onto other shows, the staff got smaller. A lot of the people I hired on Rutherford Falls had only been in mini-rooms and didn’t have any on-set experience. What I didn’t realize until after I left Happy Endings was I had this wealth of knowledge. What’s happening now with these small orders and small rooms is you have a whole staff who has been writing, they’re moving up the ranks, they might be like co-EP level, and they’ve never been on set. They’ve never been in a production meeting. They’ve never been in an edit. So, when they have a show, they don’t have the experience to run it. It allows outside forces to be like, “Well, you don’t really know what you’re doing. So, we’re going to pair you with this powerful director or producer.” It is changing fundamentally how television is made. Television has its own workflow and it worked so well because it was people who knew what they were doing teaching people who didn’t know what they were doing so they could go on and teach other people. And that key element is missing in the past decade. We’re trying hard to fight to get that back.

BYCEL I was lucky enough to learn the good and bad when I was coming up. The white dude had a long, nice run. And it’s good to hear different voices and those people have shows, but we’re screwing them if they don’t know how to run them. Mindy Kaling, when I was working on The Mindy Project, said, “I get one chance; you guys get a million chances. If I don’t do it, right, I’m not going to get another chance.” We’re spending all this time — rightfully so — bringing up all these new voices, but if they don’t know how to run their show, or they get paired with someone who sucks, or who wants to take over their show, then all of a sudden, it’s their fault. And that seems like it’s like cutting off our nose to spite our face when we’re trying to have all these new voices.

WINSTON I was talking to a writer on the picket line who is a supervising producer under an overall deal and she had been meeting up until the strike to go run shows — and she has never been on set one time. I said, “Ask yourself: Why do they want you to get this title of showrunner if you don’t have the experience to do the job?” That’s the real question, right? Because they want to create this fake position where the line producer is really in charge and they don’t show the showrunner the budget. They want to change what a “showrunner” is because they know they can’t do the job without everything we laid out of how you become a showrunner. They don’t want showrunners like there used to be. There’s a reason why they’re starting to restrict access of information to showrunners. This feels, sadly, like a bigger plan beyond just the staff size issue where they’ve said, “Oh, it’s a budget thing.” I was not sold on the minimum writer requirement at first. Once I heard [WGA negotiating committee member] Mike Schur talk about it, I was sold. We are fighting for something we never knew we had to fight for.

Why would the studios and streamers not want showrunners to know their budget or to have access to the information that they typically need?

WINSTON If they limit your ability to make changes in the budget, they can control exactly what happens. On my most recent show, I had to fight for the writers to go to set for their episodes. And it was one of those issues where if I had not had access to the budget — which some showrunners are reporting that they do not have access to anymore — I wouldn’t be able to say, “Let’s find this money somehow.” Or when they told me that what I wanted to shoot was not shootable, then I wouldn’t be able to say, “No, it is shootable, but we need to shoot a shorter episode.” So unfortunately, it just allows people to control things on a studio and network level where they have people that work for them versus showrunners where sometimes they feel showrunners are off doing their own thing.

GROFF The greatest shows ever have been made by showrunners with a lot of power, who know how to make their shows and work with their staff to build a voice and a specific tone. They have that control partly because the broadcast network model has become diminished and they’re able to almost go to a feature mentality. In addition to the line producer, it’s also the idea of a producing director who can be seen as the showrunner. Without the writers and the showrunner at the helm, the pipeline would not be filled. The short orders are allowing them to insert a line producer or producing director, but it works best when there’s a showrunner with an overall vision for what they’re doing. You need that tonal unity. A writer being in charge of it makes for the best TV.

PENNY You’re really seeing that in those Marvel TV shows because they don’t treat the writer like a showrunner and they talk to the director as if they’re the showrunner. And that was so bizarre to me.

BYCEL They are the showrunners on those! I know someone who’s a huge feature writer who had a Marvel show and he wasn’t even on set because they didn’t even want him there; they only wanted to talk to the director. They’re leaning on the line producer or the producer to tell them what they can and cannot do when they don’t have that history of experience of saying, “Well, we did it this way on one show and I saw a showrunner do it this way.” By putting those people in that position, they’re immediately able to take the power because that person doesn’t know what they don’t know.

ORNELAS I also think it’s trickling down to the viewer. How many times have we seen a show that doesn’t totally make sense by the time we get to the end? It’s because you didn’t have a room of people breaking that story together, writing that story together, rewriting it together. You didn’t have ambassadors for each episode following it through to production, remembering those things so that if something’s getting rewritten in episode seven, the person who wrote episode two is like, “No, that’s going to screw up a thing that we started over here.” There isn’t a lot of thought that goes into it because these aren’t little movies. It’s not the same medium. You see a lot of people complaining about television now, that it’s not how it used to be. And everyone’s wondering why that is. And I personally think this is why that is.

David, Jonathan was talking about the idea that a show could be perceived as being the product of the producing directors and that could be more likely to be the case where you have a creator who hasn’t done it before. You had not done this before. How did you focus on keeping Happy Endings as a writer-centric project?

CASPE I got super lucky. Probably 99 out of 100 times, it would have gone the other way. I originally pitched the show to [former studio chief-turned-producer] Jamie Tarses — rest in peace — and she was fiercely protective of me. I needed someone to partner with showrunner-wise because I knew nothing and Groff was the first. I was a big fan of Conan, which he ran, and we hit it off. He could have completely taken the show from me without me even realizing it. Groff, from day one, was here to help me find the show that I wanted to make.

Many of the people on this Zoom came and worked on the pilot. So many of the jokes in the pilot are not mine, and that was a big adjustment. Groff and I talked about it a lot, as I had come from a feature career, and this was a real adjustment for me to write with other people. If you have 15 of the funniest, most talented people in the world who, in their own right, you know are going to go on to make their own shows, if you have all them working on your thing, it’s better. No one can write the amount of jokes that a room like that can write. No one can come up with the amount of stories or make the stories make sense, or twists or whatever. This show was 1,000 percent written by the entire room.

For the three showrunners — David, Jonathan and Josh — was staffing a room with 17 people considered the norm in 2010? How have you seen room size change over the years?

CASPE Mine are much smaller now.

BYCEL We had a lot of staff writer teams. I was on a team, and it’s sort of a cheat in that you’re getting two [staff writers] for one [slot]. That’s why we had more, but I came from American Dad and we had over 20 writers.

GROFF The other thing that makes the headcount go a little higher is the show was produced by two studios — Sony and ABC Signature — and we were able to draw on some of the writers who were on overall deals. They would be with us for a few days a week. That’s another thing that’s going away, as they aren’t as prevalent as they used to be. But it was a way, I think, of building up experience and you would be able to get those people and they could run the numbers so that it didn’t hit your budget in the same way, which made it great. It was a big room for a live-action show. David’s show was about people in their late 20s and early 30s, and David wanted people who had recent connections to that.

BYCEL Because the show is so joke heavy, we had a joke room, and that was a great way for everybody to get to be a piece of the show early on.

DANIEL LIBMAN We were in a joke room and churning out joke, after joke, after joke. The cast was so afraid of the show not being funny and we were just like, “Well, can we put in more jokes?”

CLARKE Can there be a joke inside of a joke inside of a joke? (Laughing.)

DANIEL LIBMAN In a lot of ways, we had the resources to designate a joke room. It’s how the show took its tone eventually.

How rare it is to have that kind of breakdown or separation between a standard writers room and a “joke room”?

BYCEL We had three rooms. When you’re doing a network TV show, you have episodes being shot, scripts for others being rewritten for the next week and episodes that have to be broken. We would have a story room where people were breaking stories, then a rewrite room where people were rewriting the script that had to table read either that week or the next week. And then we had a joke room, which was happening while people were rewriting the scripts, we would say, “We need a better joke here, or we need a line from Max here.” The joke room would work on that. It was fun when it was like 6 p.m. and the rewrite room had finished and they would bring the jokes in and would read them out for everybody and perform them. All three of those things were going on.

GROFF We also stole a page from Bill Lawrence [Scrubs, Ted Lasso, Shrinking] where when an outline had been approved, before they would go off to script, we would have the joke room offer some funny stuff to take with you to the script.

DANIEL LIBMAN That’s something we’ve implemented on every show we’ve ever been on after.

RUBIN It’s a great idea. You’d have three rooms working and you’d also have somebody on script, and you’d have some writers onstage; this idea of a division of labor. If you talk to friends who have these mini-rooms, they lose the writers room as they then go into production. It just feels super daunting to be a showrunner in that capacity. All of your buddies are gone.

BYCEL You wouldn’t be able to do your show. Dan, Night Court is a multicamera show, you would never be able to do that.

RUBIN Right? In that case, your joke room is onstage.

GROFF Prentice, was HBO good about letting you have your staff through production? How did it work on a premium cable show, Insecure?

PENNY We had to have mostly all of it written before we shot because Issa Rae would be in 90 percent of the scenes. The last season we carried multiple scripts into production. There was at least one writer from the room who was always on set. It might be Amy covering episodes one, three, five and seven and the other one covering the even numbers. But they weren’t paying for anybody to hang out. So, we could have other writers come — and thank God those writers wanted to learn —

ANIOBI I honestly couldn’t imagine doing it with fewer people. It was even hard that way with one writer doing prep and one writer doing post. There were always things that you were missing. If you rewrote something, in between scenes you’d have to be like, “We just changed this, so can you have her say this line instead?” Doing it with even fewer people — how it’s done now with so many rooms, especially at Netflix — that’s fucking egregious. It feels so destructive to the creative process to not have a writer carry on through production.

GROFF I did Freeform’s Everything’s Trash last spring in New York. They delayed picking it up and then they wanted it delivered fast. I saw how bad it can be when you have no help. The room wrapped by the time we started production. I did ask Disney if people could be extended and learned to my horror that they could, but they wouldn’t pay them any additional money, which sucked. Once those few people finished, I was completely alone running from stage to production. We wrapped last year on July 3, and we dropped our first episode on July 13. They wanted to air two episodes within 10 days. I’ve never worked that hard in my life. It almost killed me running from being the only one on set to trying to edit on location with an editor in either New York or L.A. with an internet connection that didn’t always work on location. My line producer said he’d never seen that work, where the showrunner can edit on location.

BYCEL Studios have offered to allow us to have our writers be interns on the set, and that seems like it can solve the problem …

WINSTON One intern, like it’s a contest.

CASPE I’ve done what Jonathan’s talking about for the last three things I’ve had, where I’m editing and sitting in video village between takes, like, trying to edit at the same time.

WINSTON Not only is it impossible to physically do what you guys are describing, but you can never make mistakes. It may be hard to believe looking at this murderers’ row of writers, but they came up with some absolutely terrible pitches! With that many writers, you can throw it out and have another story by the end of the week. There was freedom to go down bad roads that you ended up not doing but later can come back to because it was fun. You didn’t have somebody constantly saying, “We can’t go down that road because we don’t have the time.”

GROFF I’m sure you’ve all had this experience on a show where you rehearse it, and it doesn’t work at all, so at the very least, you need a couple of writers on the set to help the episode writer and the showrunner figure out that scene. Numerous times on Happy Endings, Black-ish and other shows, I would call the room to do a quick rewrite of the scene with the brilliant people we had in the room. That’s impossible when you’re doing a streaming show with 10 episodes and your writers are already on another show. It’s bad for the final product.

ORNELAS On these mini-rooms, all the writers go off to script and aren’t paid for the week that they’re writing. If that were me, I would not be putting in my best effort because I’d be running around trying to find another job while I’m also expected to write the script. You turn it in and you’re like, “Good luck, I hope it works out for you,” because you’re not getting paid to rewrite it. And they’re all being written at the same time, so if your show is serialized, then your showrunner is left with these eight Frankenstein scripts that they have to make sense of as you’re going into production. You’re being set up to fail. If you are a first-time writer, if you’re a writer of color, if you’re a woman, that shit is 10 times harder for you because you’re not allowed to take up space in that way, so you have to eat it and keep going, and eventually you burn out. And those writers didn’t learn anything and the showrunner is put in an unfair position. All of it is bad.

BYCEL Do you get a script fee in a mini-room?

ORNELAS Yes. But that’s your payment. So, you don’t get paid that week that you write it.

PENNY A friend of mine was running a show for Sony and they threw out her last three episodes and she had to break them all over again by herself. They had just started production on the pilot and had cut the room and weren’t allowing her to bring back any writers, all while she was on set. She was like, “This is insane.”

GROFF That happened to my friend Kristin Newman. The platform asked for a massive rewrite of the last two episodes. She’s like, “Who’s doing that?”

STRACHAN In addition to size on many rooms, some people are getting 10 weeks to write the entire show. That leads to the compartmentalization that tech companies are looking for: You do this job for a short amount of time and then it switches to these people, instead of it being this time for growth. And they try to hire you as a staff writer for as long as they can. My first year on Happy Endings, I was a story editor and because we had time and because of the senior people on set, lower-level people got opportunities. There was time to give them opportunities. My first year, Groff let me run a story room to break a “C” story. Giving people skills so they can grow is huge.

PENNY It takes a second to even figure out what the show is and to build chemistry. A lot of us worked together [before Happy Endings] on Scrubs, but we still had to find our own chemistry. Now imagine shows where nobody knows each other and you have to figure out how you’re going to work together as a room. And by the time you’ve learned how to function as a group, it’s over.

CLARKE When I was co-running [Netflix’s] Blockbuster with my friend Vanessa Ramos, we were the only two people in Vancouver. Seven actors got COVID-19 and we couldn’t push and had to rewrite everything ourselves. On Happy Endings, an actor dropped out right as we were going to shoot. Everyone pitched in and we fixed it together. But when it’s only one or two people doing it, it’s a herculean task that is never really going to end well for anyone.

CASPE Everyone dreams of creating a show and getting it on TV, which puts you in this weird position because when they offer to make your show — and this has happened to me on every show I’ve done — [the studios] are like, “We’ll do it for this number if you give it to us in a month.” Who can say no to that?

WINSTON We need protection from the WGA so that you don’t have to make that choice. That would help everybody if they can’t make us do that.

ZIMMET If that was me, I want to seem like a team player and be someone they want to hire again, so I’m going to make this work. And that seems unhealthy. But you do it because it is your dream and there are limited opportunities.

BYCEL It also makes no sense. If they allow us to make better shows, they’ll make more money because the shows will be better and they will have to make fewer new shows because the shows that we made are good and we had a more time, with more writers and we’ll be able to keep those shows on the air, which will also allow them to make more money.

ANIOBI But if they allow us to make better shows, AI can’t take our jobs. I feel like it’s connected: the worse our shows, get the more we’re easy to replace by machines.

STRACHAN This is where the bodies that make up the AMPTP differ. The networks versus the Netflix pump-and-dump philosophy, where they cancel you because they need new content and don’t care if it’s good or not. It’s not about building an audience; they want a new show that’s going to get new subscribers.

And the reason so few shows make it to seasons three or more is because the costs are almost double what they were in season one. The model is not set up to support artists, but rather making money.

PENNY They’re all in the business of being profitable. They’re cannibalizing themselves. But they have no problem paying Ted Sarandos and those guys $80 million in bonuses. It’s just, where do you want your things to go? That’s what it comes down to.

GROFF The predicament that we’re in is totally a self-inflicted wound. The business worked for a long time, where you made stuff and you sold ads, or you sold tickets, and you had a sense of who was watching and showing up. Then we decided to pitch it to be like a tech startup.

BYCEL Cable television was a money-printing machine. I don’t have a problem if my show has ads in it. The funny thing is they all went away from the old model. Take us back to that! It’s just so stupid that they went away with that to drop 10 episodes with no ads.

GROFF They want to blow up the norms and then go back to a revenue model that actually makes sense — but having broken our union and possibly everybody else’s union.

What are some of the things that you brought from your experience in the Happy Endings room to the other shows you’ve worked on in the years since? Did you ever face any roadblocks from the studios or the streamers?

ORNELAS One of the upper-level writers said, “Put funny people in your funny pilot.”

GROFF I worked with an executive producer named Vic Kaplan who said, “Put funny people in your show.”

ORNELAS When we were casting Rutherford Falls, Jana Schmieding — who was a staff writer on our show — auditioned to play the lead. She’d never done anything in terms of professional acting. And she was so funny. And I remember weirdly hearing Groff’s voice to “put funny people in your funny show.” I knew I had to fight for Jana. You guys had put Adam Pally in Happy Endings and he had never done anything before that. But there are outside forces that will try to put things in your head: “What about data?” Sometimes you’ll push for stuff and people are like, “How did you know you could do that?” Because I worked on network television in the early aughts.

CASPE The best way to learn is by doing it. That’s really what’s at stake here.

MATTHEW LIBMAN I’ve worked consistently since Happy Endings, and not a day goes by where I don’t think about something I either directly learned from Groff, Bycel, Gail Lerner and everyone else. We all got so lucky. On paper, you can say you need this many people, but you could have that and not get the thoughtful training we got from these people who ran the show. It was such a blessing. Episode 111 was our first episode of television we’ve ever written. Daniel and I got sent to run a production meeting. And I did not know what a production meeting was. I had no supervision at all and walked in and there were 40 people at a table and it’s: “Jane goes grocery shopping. What does she have?” I was like, “Holy shit I have no clue!” (Laughing.)

GROFF That was total malfeasance on my part and I apologize. (Laughing.)

MATTHEW LIBMAN It was amazing. Prentice was on set with us and maybe someone else came in. We asked questions if we didn’t know the answer. We took so much from it.

PENNY There’s an endless amount of things that I learned. Nobody was stars on Happy Endings, almost everyone was new. When we were casting Insecure, and typically for Black shows or Black movies, it’s like, “Let’s put Ludacris in it! And let’s just pick people that Black people will fuck with.” And that’s going to be the cast. I had just watched this work on Happy Endings, where they just cast all new people, and we wanted to do the same thing. The other thing that I definitely subscribed to was everybody on the show is so funny and talented and everybody was so specific. I didn’t feel that there was a repetitive voice in the room. That was a big thing that I took when I was staffing Insecure. I wanted everybody to be specific in terms of what they were giving me. I’ve been on other shows where we had five guys that were kind of the same guy.

CLARKE I took so much stuff into other rooms. A joke room was a nice place to put newer writers because you could make mistakes. The first script Gail and I wrote, we did the wrong formatting and the script was like 38 pages. There are other shows where you would have been axed for that. You could make mistakes.

WINSTON Not only could you make mistakes creatively, but you could be yourself. There was enough time and enough other people that you didn’t have to be good at everything and we became like a family in the way that everybody knew their flaws.

GROFF That’s a great point. The idea of these small staffs — or it’s all just top heavy with a couple of co-EPs or upper-level people and maybe you hire a staff writer — you need to have people who have strengths in different areas. Some are good storytellers but their jokes aren’t going to be as great, and that’s OK because they’re going to tell an honest story from their life and you have six other really funny people who can punch it up.

BYCEL One of my favorite moments ended up being in a script that Leila and I wrote together came from Hilary being a wedding at a Skype table —

GROFF — with Brian Austin Green dancing with Penny via Zoom.

WINSTON The next level of hell would be the Skype table. It was from me having been at a wedding and being at the rando table. It was a story about, what could be worse than that? What if it was Skype.

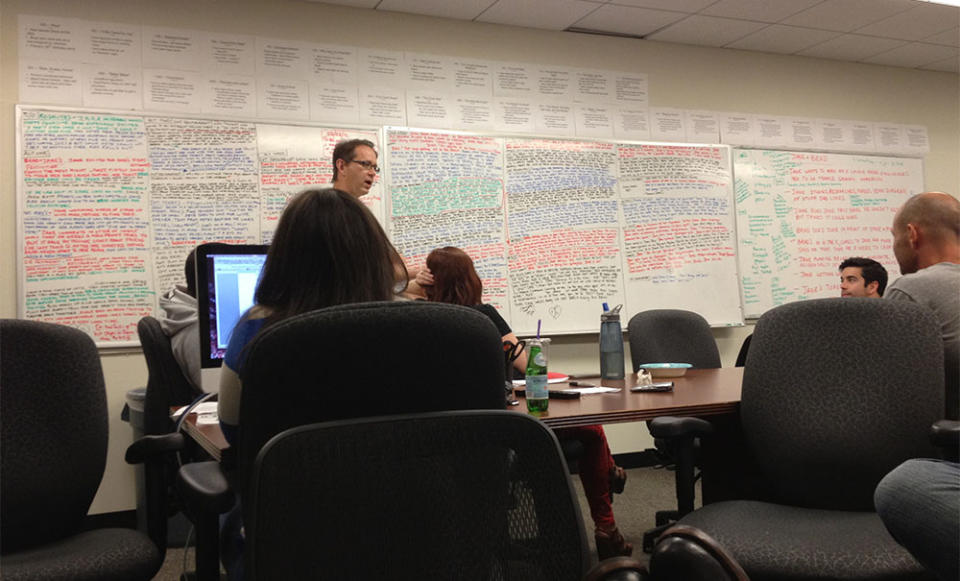

BYCEL But that’s because we had the time. That was how we broke our stories; we wouldn’t even bring Jonathan and David in until we were at that level. The board was like A Beautiful Mind.

BYCEL I never understand on shows where writers get blamed for doing things wrong that the showrunner has kept in their head the whole time. The whole idea of training other people is so they’ll take the work off your hands.

MATTHEW LIBMAN We all felt ownership of the show so much, which made us, as the staff writers, want to work harder because we were being encouraged to learn. The culture for us after work, we’d hang out on set for hours and spend time with the actors. I’d never been on set and didn’t know what coverage was. Being around set and being encouraged to learn and being shown the ropes, by the time our episodes came around, we had a handle on it.

DANIEL LIBMAN That’s the thing that’s so interesting to me about writing all the episodes and then kicking everyone off the staff: What we learned on Happy Endings was a level of collaboration between the writers and the actors, with pitches from everyone on stage. You’re not done when you finish writing; you’re just starting. You make the show on set and in the editing room. So that idea that once you finish writing, that anyone can just make the show? This show is proof that that’s absolutely, fundamentally false.

Sierra, in her thread, quoted Prentice saying that the “showrunner is the painter and we’re the paint, figuring out your color and when they need it, be that color. Don’t try to be someone else’s color.” That’s the kind of thing where it sounds collaborative, but it could just as easily become autocratic …

PENNY When I was starting off, I was guilty of this early on, where I was pitching something and wondered why it’s not getting into scripts and watching young writers get things in and thinking, “Maybe I’ll pitch like that person.” It’s changing who you are by getting caught in the minutiae of arguing with the showrunner, when the showrunner clearly doesn’t want to go in that direction.

ORNELAS When Prentice said that to me, I had forgotten that Groff told me what he wanted me to be for this room: story, fixing problems, going to the people that I knew wanted to hear from me. Then, over time, you get better in these other areas.

ZIMMET There are people who like sitting alone and writing, and then all of a sudden, you’re in a position where you’re then running the show, managing people and figuring out how the show works. And you might not have those managerial skills just because you’re good at writing stuff down. But that’s why rooms like Happy Endings are helpful in that you’re learning how to run rooms like Leila did as a story editor. When you take it piece by piece, by the time you run a show, you know what you’re doing a bit more.

PENNY Having writers stick around is important because you need to see that part of the process. Being a showrunner is different than being the best writer in the room. Those are two different skill sets. There are people who are really great writers that are horrible [showrunners] and don’t want it because they are horrible at managing people. If you’re not around to see how those skill sets differ, then you won’t learn.

GROFF My boss/partner after Happy Endings was Kenya Barris at Black-ish, and nobody had a stronger voice and point of view than Kenya — and he’s hilariously funny. He wanted his writers to share their stories and said the show would be better if he had young people, old people, white people, women, men telling him what their experiences were. He and David are the same: “Help me do this.”

BYCEL You need those two weeks at the beginning of the season when it’s just the writers shooting the shit and figuring it out. It’s amazing what you will come back to years or months later where you don’t have to break an episode in two days and you end up having to be autocratic because you don’t have time to even realize if someone else has a good idea or not. You don’t get good TV that way.

PENNY These companies do it — they just call it a corporate retreat.

The use of AI has been wildly debated. The DGA just got some protections from the AMPTP there. The AMPTP offered the WGA an annual conversation about technology, which was obviously rejected. Have you each thought about if AI is something you’d use?

STRACHAN I keep hearing this example about one day, you’ll have a story problem and need three different ways the scene could end and you just tap into the AI machine and you get all these ideas. Isn’t that what writers are? Every example where a writer could use AI, I’d rather talk to a person and come up with something even better. There are rumors that like Paramount is building script writing software, and I’m sure they are, but I’m like, “Yeah, to make things that aren’t very good.” I know AI is a threat and we have to protect [ourselves from] it today, because one day it will actually be good.

BYCEL It is coming and it’s up to us to figure out how we can use it to our benefit. Maybe it is an outline or a story area — which everyone hates writing anyway — or helping to keep the show bible.

WINSTON I’ve been getting into ChatGPT for research and it’s just really good Google at this point. I think we need to use it as a tool. I don’t think it’s going to be writing for us or doing a good job. I certainly wouldn’t trust it to write a story area.

STRACHAN Six months ago, I thought, there’s no way AI can do anything close to what we do. And I still believe that’s true. But I was terrified by the studio’s refusal to even discuss this. That’s bad. It’s like, “Oh, gosh, you are building shit.”

GROFF It’s economics. They’re going to have a shitty boilerplate AI thing and then they’re going to say, “Make this, we know we need you.”

PENNY We need you to make it better, do a rewrite.

GROFF That’s why they’re stuck on the minimum room size. They want to get it down to the minimum number of people that they can and that’s a way to do it — you’re rewriting a terrible writer’s draft.

CLARKE The network can just type in their notes to ChatGPT and rewrite it that way.

ORNELAS How are the execs not getting replaced?! I hate it all. I don’t want any of it. Everyone knows it’s easier for six people to write a draft than to get a bad draft in and have to rewrite it. It just sounds like more work for the humans. I don’t understand how it’s going to save us any time until it gets smarter. My problem with AI is that it’s a regurgitation of everything that’s come before us. So, if you’re looking at Native American representation, that’s fucking terrifying because whatever it bleep-blurbs out is not going to be anything close to something that me or all the Native writers that I’ve hired or work with can offer. When it comes to writing that’s specific, it bothers me that right when brown people get a chance to start making shit and be in charge is right when the robots come. It just it makes me so angry that everyone thinks this is innovation, when it just feels like the same thing that we always have to deal with.

STRACHAN It’s a regurgitation of people who write a lot on the internet. There are some good things on the internet and then there’s a lot of people writing really horrible stuff.

BYCEL 99.9 percent of the stuff on the internet is still terrible.

STRACHAN Would you want to get a draft where these jokes are from something else entirely?

CLARKE It’s plagiarism.

WINSTON I asked ChatGPT about a restaurant in L.A. and the results were that it was in Boston. I said the information was outdated and then it said, “Sorry, my information only is current of like, 2017.”

About half of you are also DGA members. What do you think of the proposed deal and how might you be voting?

ANIOBI I’m still undecided because the DGA has worked in silent for so long and then they’re like, “Celebrate this win.” I don’t even know where we started. It feels weird that the contract was ratified 48 hours before the SAG strike authorization vote. If they would have just waited two days for that strike authorization vote, who knows what the DGA could have gotten. It feels shrouded in mystery, which makes me feel very undecided.

PENNY I don’t like what they did at all. I’m skewing toward “no.” The DGA is notorious for not striking; the longest they have is like three hours. I think they should be more worried about AI — “Hey, can you put a camera here and just get the basic coverage?” — that’s much more concerning thing than trying to farm ideas from people’s backstories that grew up in very specific environments.

GROFF I’ve been following the lead of some people who have been outspoken about it, whose instincts and analysis of it I trust. I understand it’s going to probably be approved overwhelmingly because so many assistant directors want to work. I agree they made a mistake on AI and didn’t exert enough leverage. Some of the things are galling, like building an extra day in for directors to do a director’s cut off of producer notes. With all due respect, I love television directors, but give me your cut and let me edit it. That’s going to add money in postproduction. The fact that the studios actually took the hit on that when that day of postproduction could pay for another writer.

CASPE Everybody watches a TV show or a movie and says, “I would have written it this way. I wouldn’t have written it that way.” There’s a general feeling that writing is nothing when it really is at the core of all of this entertainment. I mean, there are restaurants based on ideas from writers in movies.

Wrapping up, we are in a world in which everything is getting rebooted, and there have definitely been rumors about more Happy Endings. How often do you think of this as a world you’d like to return to?

BYCEL Doing the Happy Endings podcast, we are doing one episode that’s going to be a special little thing.

CASPE There simply are not enough people that want to see it. It is a very vocal group, and I would not want any other group of fans in the world. But it just seems to not quite be enough people for anyone to actually put up millions of dollars.

CLARKE We’ve also done the Zoom cast reunion during the pandemic, which I think was one of the best things we’ve done.

GROFF The next time there’s a worldwide lockdown, we’ll do another thing.

This interview has been edited and condensed. The full conversation can be heard in episode 218 of TV’s Top 5. Click here to listen and subscribe on your podcast platform of choice.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter