An addictively readable history of the Hollywood Renaissance, with one glaring omission

Reassuringly, the two golden ages of American film each arrived in the wake of utter chaos. The roughly simultaneous advent of talking pictures and the Great Depression ushered in the glories of the 1930s; decades later, the collapse of both the Hollywood studio system and American optimism in Vietnam helped soften the ground for such 1970s classics as “Chinatown,” “The Godfather Part II” and “The Conversation.”

And those particular gems weren’t just great movies from the ’70s. They were, amazingly, great movies from 1974. Also celebrating their golden anniversary this year are “Scenes From a Marriage,” “Swept Away,” “A Woman Under the Influence” and — at least as important to some of us — “The Parallax View,” “Blazing Saddles” and “The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3.”

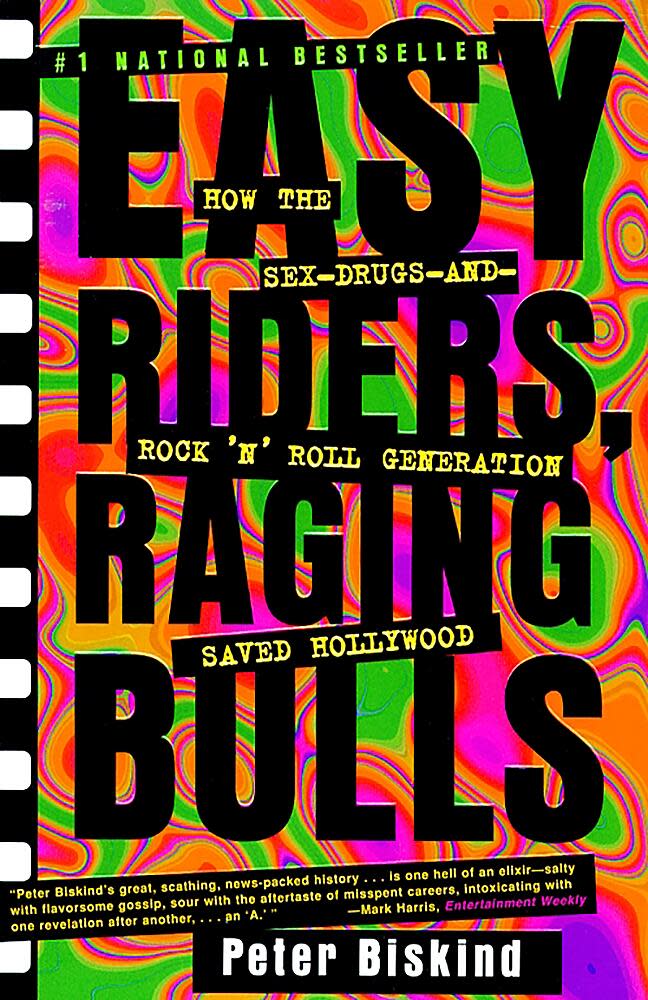

In other words, 1974 in film was, to say the least, a very good year. And among the best places to learn about the irresponsible people responsible for it remains Peter Biskind’s addictively readable "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls."

Biskind’s book does ample justice to all three pillars of its benevolent subtitle, “How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock ’n’ Roll Generation Saved Hollywood.” But he doesn’t just string together juicy anecdotes about hard-partying luminaries like Martin Scorsese and Peter Fonda. He also cares about the art of moviemaking, and at least the appearance of sound journalistic practice. (If you want to get drunk in a hurry, just drain a shot glass every time Biskind writes something along the lines of, “Dennis Hopper denies this ever happened.”)

“Easy Riders, Raging Bulls” is almost but not quite that rare thing, a terrific idea for a book that actually became a terrific book. Biskind talked to just about everybody still around and quotable in 1998 — although some, such as the great screenwriter ("Chinatown," "Shampoo") and director Robert Towne, may now regret it.

Poor Towne. "Chinatown"-style, Sam Wasson’s book “The Big Goodbye” likewise shoves a switchblade up Towne’s coke-frosted nostril too, giving overmuch credit to director Roman Polanski and studio head Robert Evans. But Towne’s own book, if he ever cares to write it, remains the one I’d line up for on opening day.

Never one to stint on gossip, Biskind re-creates the heady years at a certain A-frame on Nicholas Canyon Beach in West Malibu, where up-and-coming directors Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Brian De Palma and Paul Schrader all competed for the attentions of housemates Margot Kidder and Jennifer Salt — and for each other’s projects. (Salt’s life too, with a character arc from blacklisted screenwriter’s daughter to directors’ muse to TV writer-producer, is a memoir waiting to happen.)

But something’s amiss when even a good book keeps making you hungry for other, unwritten books instead. Like a bad director, Biskind just keeps pointing his camera in the wrong direction. He adheres to the pervasive, pernicious auteur theory, which insists that even non-writing directors are the “authors” of their movies.

One result of auteurism is books like this, which cast directors as larger-than-life characters making extraordinary art despite all the philistines around them. Responsible for such laughably reductive shorthand as “Scorsese’s 'Taxi Driver'” or “Hal Ashby’s 'Coming Home,'" auteurism is the taxonomic convenience that became a religion.

Consequently, the mostly missing pieces of Biskind’s story are the screenwriters, without whom none of these brilliant pictures would ever have seen the light of a projector bulb. The only gifted writers whom Biskind pays much attention to are Towne, Schrader (“Taxi Driver”) and John Milius (“Apocalypse Now”) — each of whom sadly treated screenwriting as a steppingstone to their own less illustrious directing careers.

It’s almost funny. We’re treated to scene after scene of Scorsese waiting around in frustration for Mardik Martin to write “Raging Bull,” or Dennis Hopper for Terry Southern to finish “Easy Rider,” or Warren Beatty for Towne to finish anything. All these filmmakers’ needy, importunate wooing of their writers — and their eventual dickering over script credit — makes their courtship of actual women such as Candice Bergen or Amy Irving look halfhearted by comparison.

Still, Biskind’s book more than deserves its place on our list of the best Hollywood books. It’s never less than well-written, and frequently more. You also have to give the man credit for keeping all his many characters and plotlines clear. And structurally — to invoke many screenwriters’ favorite byword — Biskind artfully begins his story of the 1970s’ short-lived filmmaking revolution with an earthquake (Sylmar) and ends it with a memorial service (Ashby’s, at the Directors Guild). Nice.

Ultimately, film lovers should be so lucky as to see another golden age to rival either the ’30s or the ’70s — despite the traumatic social upheaval that arguably triggered both. If only American society and the film industry were experiencing comparable chaos today …

Author of "The Schreiber Theory: A Radical Rewrite of American Film History" (Melville House, 2006), Kipen has written about film for, among others, The Times, the Atlantic and World Policy Journal. He is also the founder and co-executive director of Libros Schmibros, a bilingual nonprofit storefront lending library in Boyle Heights.

Get the latest book news, events and more in your inbox every Saturday.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.