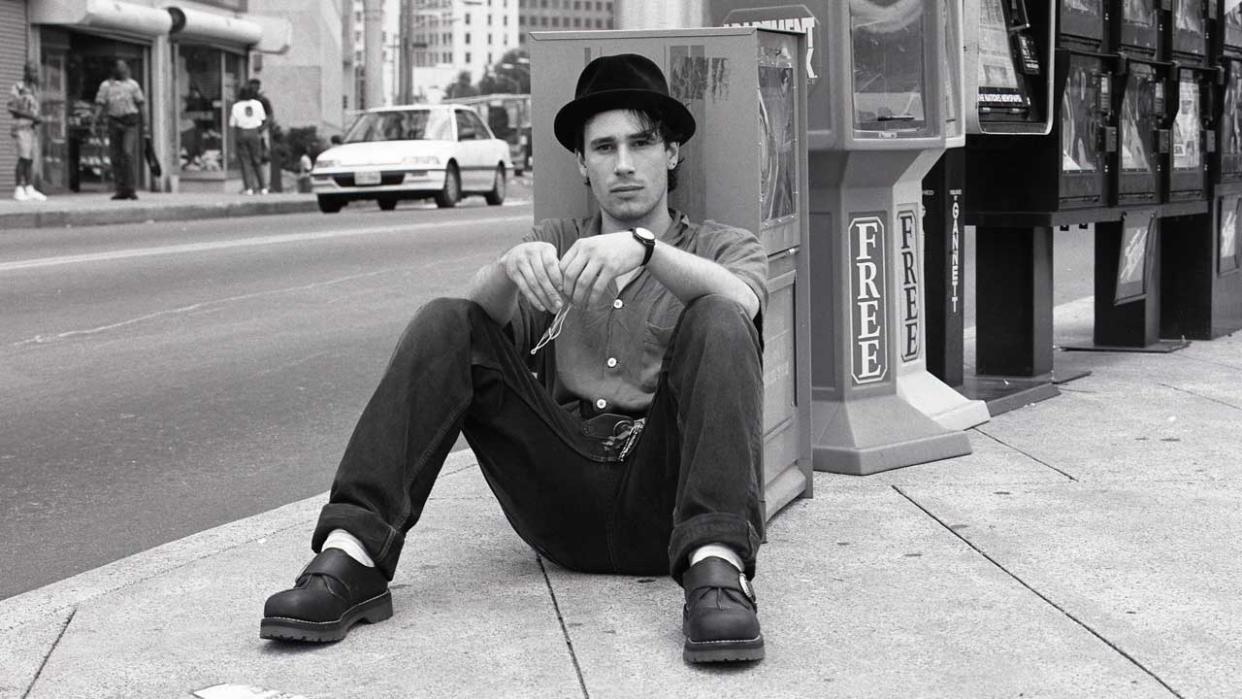

Amazing Grace: how Jeff Buckley got started on the album that defined his genius

Gary Lucas still tingles at the memory. It was the spring of 1991, and at St Ann’s Church in New York, the former Captain Beefheart guitarist was packing up his gear when a stranger approached.

“He was vibrating,” Lucas remembers. “He looked on fire. His eyes were flashing and he was jumping out of his skin. And I knew right away this was Jeff Buckley. He looked just like his dad.”

Sixteen years after heroin took Jeff’s father Tim Buckley, the celebrated folkie still seemed to cast a long shadow, not least over his son’s stuttering career on the West Coast.

“Jeff hadn’t had much encouragement in Los Angeles,” Lucas explains of the young singer-songwriter. “They kinda put him down, from what he told me. They’d say: ‘Hey man, the only reason anybody is listening to you is because of your dad.’ Nothing had quite gelled for him. Coming to New York was a fresh start. He right away clicked with the musicians and vibe.”

Twenty-four-year-old Buckley was already familiar with Lucas’s visionary guitar playing with Captain Beefheart. But it wasn’t until the day after that meeting at St Ann’s, when Lucas invited Buckley to his apartment, that he grasped the dizzying scope of the newcomer’s talent. “I’d prepared a guitar arrangement, and when Jeff started singing, my jaw literally dropped. I was staggered. He was producing an unearthly wailing that went far beyond his years. I said: ‘Man, you’re a fucking star.’”

Even after that epiphany, it took a sting of fate to make the partnership official. While Buckley returned to LA, Lucas was crushed to come off tour and discover that his record label had dropped the axe on his acclaimed solo project. “They put the junior A&R guy on the phone and he goes: ‘You can’t afford to sue us.’ So I was distraught. But then I was like, ‘Wait a second, I’m gonna call Jeff…’”

With the two men on opposite coasts, this would be no eyeball-to-eyeball songwriting partnership. Instead, Lucas initiated “solo guitar instrumentals, with all the riffs and harmonic structure”, then posted cassettes to Buckley. He remembers rising each morning at 3am to channel what would become two defining songs from Buckley’s debut album, Grace.

“I composed the music in one week,” he recalls. “I just started passing my fingers over the strings. It’s an approach where you turn your mind off and float downstream, until you hit some magic notes.”

Lucas had scribbled two titles for this music: one was called And You Will, the other was Rise Up To Be.

“A few weeks later, Jeff rolled into New York. He was playing in a show band, promoting The Commitments with one of the guys from the film. He came over to my apartment and says: ‘You know that one called Rise Up To Be? Now it’s called Grace.’ So I started the riff, and he comes in with that lyric: ‘There’s the moon asking to stay…’ He was the best co-writer I ever had. I can’t tell you how wonderful it was to work with this guy.”

With And You Will also retitled, to Mojo Pin, the pair had two standout songs that would be recorded during album sessions at Bearsville Studios in Woodstock. In their finished form, each was swooping, hypnotic and passionate, with the mood darting from jubilation to despair.

“If you look at Mojo Pin and Grace,” says Lucas, “they’re bittersweet songs, instrumentally and lyrically. I wrote them instinctively. But thinking about it years later, they go from major to minor, with verses of ecstatic joy then dark passages. I think that’s why our songs are enduring and touch people. Because no one’s life is happy all the time. Everybody has their moments, and it’s easy to slide into despondency and depression. But hopefully live to fight another day.”

Buckley’s own days were running out. Released on August 23, 1994, into a rock landscape shifting gears between grunge and Britrock, the Grace album limped to No.149 in the US. But it was one of rock’s great slow-burners, cited by artists from Steve Vai (“I was walking around in tears”) to Jimmy Page (“I played Grace constantly”).

Tragically, by the time it went gold, led into the mainstream by Buckley’s angel-voiced cover of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, Buckley was gone. Lucas prefers not to dwell on the darkness in Buckley’s character, or the events of June 1997, when his dead body was dredged from the Mississippi River.

“Jeff had different sides,” he sighs. “He had a real fun-loving side, but he did get heavy when he had things on his mind. In the book that his mother wrote, Jeff told [Television mainman] Tom Verlaine he was bipolar. That was something I didn’t know, but I thought, okay, well, that sorta makes sense. Because that would explain some of his mood swings. But I prefer to remember the fun times. I like to remember the happy Jeff.”