‘A Badass With a Gentle Side’: The Complex Life of Dickey Betts

AT A DOWN-HOME EATERY near his waterfront home on Florida’s west coast in 2017, Dickey Betts, stout and white-haired but still evoking his youthful intensity, was asked about his imposing reputation. “People are a little bit standoffish because they think if they say something wrong, I’ll be aggressive or something with them,” he told Rolling Stone, adding with his drawl, “But I’m not like that at all. Unless you start saying shit that’s really demeaning, and then I won’t hesitate to …” Betts didn’t finish the sentence, but you had a sense of what he meant. “I guess I have a face and attitude that kinda scares people.”

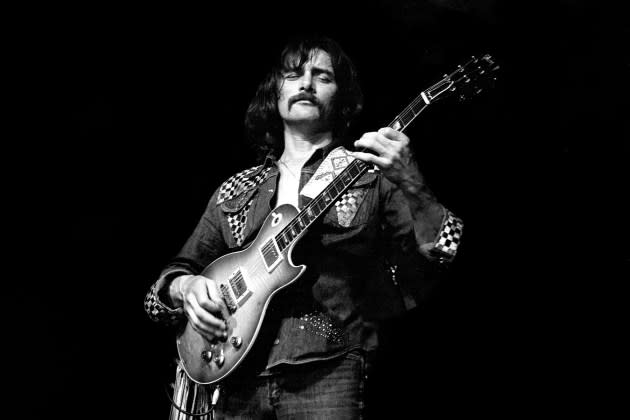

Betts, who died on April 18 at age 80 of complications from cancer and pulmonary disorder, was one of Southern rock’s — or any rock’s — most daunting characters. During his years leading and powering the Allman Brothers Band, he was so iconic — that handlebar mustache, the tight-lipped moodiness, those Western-sheriff jackets — that Cameron Crowe based the Almost Famous character Russell Hammond on him. “Gregg [Allman] had the rock-star thing dripping off him — he was a walking myth,” says Derek Trucks, who briefly played alongside Betts in the Allmans and remained a friend. “But it wasn’t intimidating in the same way Dickey was with that cowboy hat. Sometimes he tucked that hat down, you couldn’t even see his face.”

More from Rolling Stone

Where to Buy the Bestselling 'Brothers and Sisters: The Allman Brothers Band' Book Online

Allman Brothers Band Pay Tribute to Dickey Betts: 'The Signature Sound of Southern Rock'

Watch Dickey Betts Play 'Ramblin' Man' at Final Live Appearance in 2018

“It’s quite a blow for me,” says Warren Haynes, who played in one of Betts’ solo bands in the Eighties before joining the Allmans afterward. “We played a lot of music together and logged a lot of miles. He’s the one who gave me my biggest break when he brought me into the Allman Brothers, and a lot of doors opened due to that. I’ll forever be grateful.”

Everybody has their “good Dickey and bad Dickey” stories, says Richard Brent, who runs the Allmans’ Big House Museum in Macon, Georgia, with a fond chuckle. Trucks heard about the time one of Betts’ solo-band members walked out of his hotel room to find Betts, an avid hunter, shooting arrows down the hallway. (“But I’m not a nut, like Ted Nugent,” Betts later told RS.) Betts’ legend includes a jacket with “Eat Shit” emblazoned on its back, and chopping up the furniture in his house during a dispute with one of his five wives, according to Scott Freeman’s Allmans bio Midnight Riders. “He was very gentle inside,” recalls the Marshall Tucker Band’s Doug Gray, who toured and partied with Betts in the Seventies, “but don’t rile him up. Don’t give him a reason.”

Gregg Allman’s son Devon said he was “scared shitless” when he first met Betts in the late Eighties, when he joined his father and the reunited Allman Brothers Band on tour. Betts seemed to be giving him the cold shoulder during early gigs, until one aftershow party, when Devon got up to sing. “This dude with a hat, out in the middle of the room, stood up and it was Dickey,” Allman says. “He ran over to me, after being pretty chilly on the tour so far, and extended his hand and said, ‘Man, I didn’t know you could sing like that.’ He was still a badass, but I got to see a sweet, kinder, gentler side.”

In addition to seemingly hundreds of stories like that, Betts also left behind a trail of arrests and rehab stints, the stuff of outlaw legend. “It’s no secret that my dad raised some hell in his life and got kicked off of a few airplanes,” says his son, Duane. “We all have demons we have to deal with, and he was no different.”

Precisely what Betts’ demons were was never quite clear. The son of a carpenter who played fiddle, Forrest Richard Betts was born and raised in Florida. He would hint at turmoil in his upbringing: “My dad came home drunk one night and broke my ukulele,” he told RS in 2017. “But you don’t want to read that shit!”

Betts channeled those troubles into some of the most exquisite moments in a genre, Southern rock, that prided itself on its Hungry Man brawniness. Listen to “Revival,” the joyful singalong he contributed to the Allmans’ second album, Idlewild South, or “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” the haunted, simmering instrumental on the same record. And, of course, “Blue Sky,” his bighearted love song that soared into the ether. He and his bandmate Duane Allman were perfect musical foils, with Allman’s lacerating slide guitar and fiery notes balanced out by Betts’ sweeter, spiraling tone, rooted in jazz and Western swing. “When you hear B.B. King do the two notes on ‘Lucille,’ that’s absolutely B.B. King,” says Brad Paisley, who played some of Betts’ songs in his youth. “And same with Dickey. You just hear a couple of notes [and recognize him].”

When Duane Allman died in 1971, Betts had little choice but to step up even further, and it would be his songs — the easy-rolling country of “Ramblin’ Man,” the instrumental “Jessica,” or the beefy rocker “Crazy Love” — that reignited the band artistically and commercially. “The fact they were able to continue and still had an identity tells you how important he was,” Paisley says. With his first post-Allmans band, Great Southern, he hit another high note with songs like “Bougainvillea,” a melancholy ballad that shook off its blues once Betts’ guitar took over. “He wasn’t an ‘I’m gonna sit around and listen to sad songs all day’ type of guy,” says Duane Betts, who watched his dad wander around their property with a guitar as he wrote songs. “He liked to be uplifted.”

Those who knew and worked with him over the years still grapple with that duality. “He wrote some of the most beautiful rock songs ever,” says Trucks. “I’d put ‘Blue Sky’ and ‘Jessica’ against anything. For me, it was an easy lesson in the dichotomy in life. How people can be a lot of different things and there’s a lot more gray area than black and white. He was severe and intense but also a beautiful character.”

As the Seventies ended, Southern rock grew homogenized, but Betts remained his own man. Talking to RS in 2017, he bristled at the memory of two pop-leaning albums the Allman Brothers recorded for Arista in the early Eighties, saying the label wanted “a disco album” and “all our good shit wound up on the cutting-room floor.” When the Allmans fell apart for the second time, he recorded and shelved a country album in Nashville. “It was an attempt to fit in,” says Haynes, who sang background on a few of its songs. “He said he didn’t feel comfortable.”

Starting in 1989, the band members put aside their differences (Betts had initially been furious after Allman testified against the band’s drug dealer in 1976), and the Allmans regrouped yet again. Per usual, Betts stepped up, especially since Allman himself was grappling with his own substance-abuse issues. Haynes, who had been hired for Betts’ solo band right before the reunion, took note of an immediate shift. “As soon as we started rehearsing, I noticed a change in his seriousness with which he was taking the music,” Haynes says. “He had a lot more reverence for the Allman Brothers music, and was more protective of it. Not demanding, but more expecting it to be a certain way or exist within certain parameters.”

The Nineties marked a rebirth for the Allmans. With them, Betts wrote one of his standards, the philosophical country song “Seven Turns,” and 1994’s “Back Where It All Begins” demonstrated the way he could push his guitar into smoldering new heights. He took enormous pride in Bob Dylan joining him for a duet of “Ramblin’ Man” onstage during that period: “He fuckin’ sang word for word, and I told him later, ‘Those words have never meant so much in its existence!’”

But drama still followed, starting with Betts’ private offstage area, where he would sit alone while others took solos. As Betts told Allmans biographer Alan Paul in Paul’s oral history of the Allmans, One Way Out, he went on a “three-year drunk” in the mid-Nineties, and the band confronted him after Betts bailed on shows a few years later. At New York’s Beacon Theatre, where the Allmans played extended residencies, Devon Allman watched Betts storm off during a show. “He was really pissed off at his rig and his guitar, and he threw it down and split,” Allman recalls. “There wasn’t a whole bunch left in the show anyway, but it was quite the move.”

The Allmans remained a fraught band even then: “There was always drama, as far as original members not getting along and complaining, and a lot of tension at that point,” says Haynes, who left, for a time, in 1997. In 2000, Betts was out of the band after the others complained about his excesses (which he denied) and playing too loud onstage. (He would maintain that his dismissal partly stemmed from him asking for an audit of the band’s finances: “Big fuckin’ mistake on my part,” he told RS.) “To see [the band] playing all of his songs without him in it, it hurt,” says Duane Betts. “I don’t blame them for playing them. The fans wanted to hear them. But there were quite a few years there where it really hurt my heart, and I know it hurt his.”

The roughly two decades that followed brought a new set of challenges for Betts. Sitting in with the Tedeschi Trucks Band at the Beacon in 2013 and playing Allmans songs, he was greeted like a returning hero. “When he walked onstage, you could feel there was a lot of pent-up appreciation,” says Trucks. But as he soon learned, Allmans fans weren’t as eager to buy tickets to his solo shows. By the time RS spoke with Betts in 2017, he’d decided to retire from the road. “If I played new songs in my show, the audience is bored with them,” he said with a shrug. “So all of that, I said, ‘You know, I think it’s time to enjoy life.’” Betts never blamed Gregg Allman for his ousting him from the band, and shortly before Allman’s death in 2017, the two men finally reconciled by phone.

The following year, Betts put his retirement aside and played a handful of shows with a band that included his son. “I was so proud of him that he persevered and got through that tour and each show got better,” Duane says. “There were a few rough spots, but it was really triumphant and there are pictures of him raising his fist.” But any plans for more gigs were cut short when Betts suffered a minor stroke in 2018. From that point on, Betts remained offstage and out of the headlines, except for the time when his wife, Donna, was arrested for pointing a gun at a group of teens and coaches of the Sarasota Crew team rowing past their house. (“They’re high school kids, but from real rich families,” Betts groused to RS. “They’re arrogant as hell.”)

Last December, the Allman Betts Family Revival, which includes Duane Betts and Devon Allman, played a show in Sarasota, Florida, in time for Betts’ 80th birthday. The Dickey Betts who showed up was older and frailer than ever, but seemed to have reconciled with his past and demons. “We didn’t know if he wanted to get out of the house, but he came to the show and got to eat his birthday cake and got to see us play his music,” says Allman. Taking a seat by the side of the stage, Betts remained vigilant of his and the Allmans’ music and legacy as he watched the band re-create his songs, with what seemed like, at last, added serenity. “He watched every note and drank a cold beer,” says Allman, “and he said, ‘Everybody sounded so great.’”

Looking back over his life, talking with RS, Betts shook off his tribulations: “It’s complicated, but you know what? I wouldn’t have traded it for anything because I know nothing is perfect and nothing is permanent. What can I tell ya? I’m not that goddamn interesting!”

This remembrance of Allman Brothers Band guitarist Dickey Betts appears in the June issue of Rolling Stone.

Best of Rolling Stone