How Bob Evans became to Ohio what Colonel Sanders was to Kentucky

On a recent Wednesday morning, a waitress named Erin leads me to a booth at the Bob Evans location in Blue Ash. Before I even sit down to ask, she offers me a cup of coffee and it arrives hot and fast, tasting of good diner coffee, but better. The lighting here is softer and more welcoming than you would expect from a national chain, and the country music that’s playing is set just above a whisper.

Erin and the rest of the waitstaff seem to know most of the customers here on Pfieffer Road. They ask many of them if they want “the usual.” While those who’ve returned after a notable absence are greeted with an “I haven’t seen you in a while.”

After decades of family ownership, Bob Evans Farms was sold to a San Francisco-based private equity company called Golden Gate Capital six years ago. Golden Gate also owns such beloved restaurant brands as California Pizza Kitchen and Red Lobster. But unlike those places, I think Bob Evans still holds on to its identity. At least to a point.

I know a lot of people who have turned on Bob Evans since they sold to Golden Gate. “(Expletive) Bob Evans!” said a friend of mine, who grew up in Bob Evans’ hometown of Gallipolis, Ohio. He wasn’t referring to the man, of course, but the restaurants that, to many, feel like the disembodied souls of what they once were. But like an automaton that sometimes exhibits signs of real human emotion, I think Bob Evans can still surprise you with its charms.

– ?? Sign up for Keith's At the Table newsletter ??–

It’s still a place where a group of widows meets weekly to discuss their respective losses.

It’s still a place where old men tell the same bad jokes over and over (and over) to their eye-rolling waitresses.

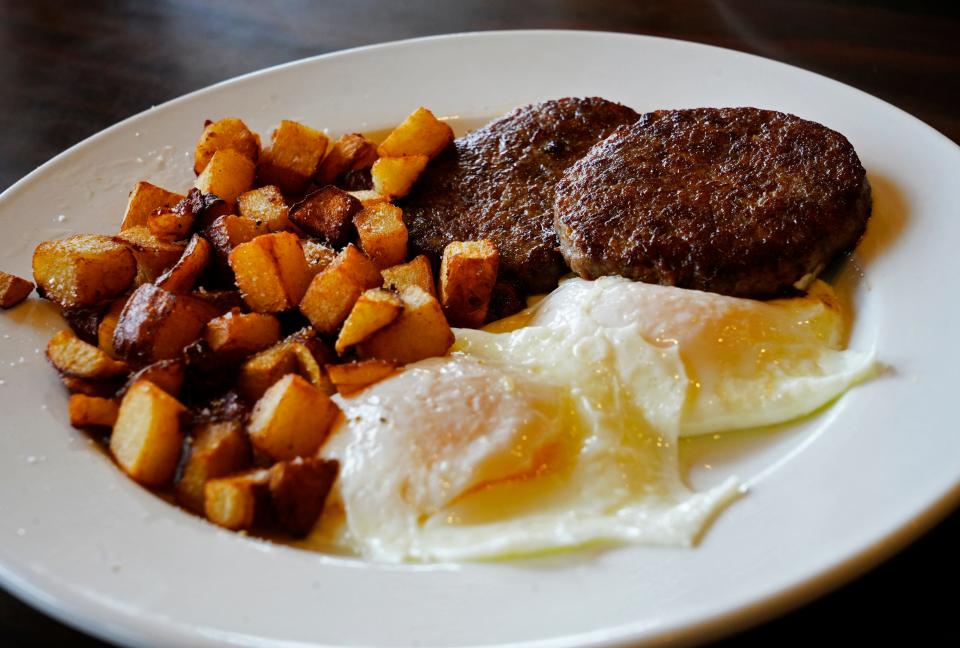

It is still a place where you can get a good biscuit and sausage for breakfast and pot roast sandwich for lunch.

Here and there you can still see traces of the restaurant’s Appalachian roots. There is a photo of the Rio Grande farmhouse where Bob Evans and his wife, Jewell, raised their children. There are photos of the rolling hills of Southeast Ohio he grew up with and never left behind.

On Pfeiffer Road, the booths are still nicely upholstered, tucked away just enough for private conversations over hot cups of coffee with biscuits and gravy. I listen to a grandmother talking to her grandson about the troubles he’s facing at work. And I listen to an older couple as they discuss a recent CIA leak they’d heard about on cable news. Several older men are scrolling on their phones or just looking around and taking everything in. I jot down in my notebook that this is a restaurant that lets you be alone without feeling that way.

Not everyone is happy, though. At one point, a businessman leaves in a huff because his food is taking too long. Erin handles it like a pro, apologizing to him as he storms out with what seems like affected rage. I swear I arrived around the same time he did and his food wasn’t taking too long at all.

“Maybe he should’ve gone to McDonald’s,” I joke to Erin.

“I’m not allowed to say that,” she replies.

I think Bob Evans would’ve liked Erin.

Bob Evans’ ‘come to Jesus’ moment

A long time ago, way back in 1980, Bob Evans was recovering from a heart attack at his home in Rio Grande, Ohio, when his attorney presented him with some documents to sign. If Bob Evans obliged, it would complete a $200 million merger of his Bob Evans Farms, Inc. – the Ohio-based sausage maker and restaurant chain – with Chicago-based Beatrice Foods.

After convalescing in Arizona, Evans returned to his farm in Rio Grande to rest while awaiting open heart surgery. According to news reports at the time, the documents would have handed Beatrice the company’s trade secrets as well as a non-compete agreement. The other eight Bob Evans board members had already signed off and Bob Evans had given every indication that he would go along with it, too.

But at the very last minute, something unexpected happened. Bob Evans refused to sign.

Evans, then 63, had gone from owning a 12-seat truck stop in Gallipolis to overseeing a $125 million-a-year company with 61 locations in Ohio, Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois. He and his cousin, Daniel Evans, 44, were the only Evans family members involved with the company, the latter serving as its chairman and CEO.

– ?? Why Frisch's is one of our most important restaurants ?? –

Daniel Evans, who had orchestrated the merger, wasn’t shy about his frustration with his cousin. The potential merger between Bob Evans Farms and Beatrice was a big deal, covered thoroughly in the pages of national papers such as the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times. So when Bob Evans reneged, Daniel Evans was frustrated. “I’m tired of going one way and then another,” he said in The Enquirer.

Some thought the reason for the sudden reversal might have been a “come to Jesus” moment Bob Evans experienced after his health scare.

But others, including Daniel Evans, speculated that the about-face might’ve had something to do with another famous restaurateur who sold off his restaurant chain only to regret it: Colonel Harland Sanders. None other than the face and founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken.

An unlikely friendship of sausage and chicken

Sanders and Bob Evans were good, if unlikely friends. According to Evans’ son, Steve Evans, the two met when his father was around 52 and Sanders was 72. Sanders seemed to like the young Evans, who, like the Colonel, started his restaurant empire in Appalachia. He invited him and Jewell to the Kentucky Derby and stopped by their house whenever he was in or near their Gallia County farm. Sanders even gave Evans his first string tie that would help cement the latter’s persona as the so-called “Colonel Sanders of hogs.”

“He was a very dear friend for a very long time,” Steve Evans told me on the phone recently. “And he was a real character.” On occasion, Bob Evans bore witness to Sanders’ fiery temper. When a waiter at a Portsmouth, Ohio, restaurant delivered a smart-aleck remark after the Colonel complained about getting the wrong order, Bob Evans watched in disbelief as Sanders, then in his 70s, socked him in the head without even standing up.

Like Sanders, Bob Evans – who often appeared in print and TV ads as a kind and friendly, salt-of-the-earth Ohio farmer – could also be cantankerous, thanks to what was often referred to as his “Welsh temper.” That said, I could find no documentation of him ever laying someone out over a botched order.

According to Daniel Evans, Sanders’ death just two weeks before the Beatrice deal was supposed to close was likely still looming over Bob Evans as he prepared to sign off. Which led to speculation that it might’ve been the reason he reneged.

After all, Bob Evans knew about the bitter feud Sanders had with the Heublein Corporation after the Connecticut-based packaged food company bought KFC from future Kentucky Gov. John Y. Brown and businessman Jack Massey for $285 million in 1971. Sanders just plain hated what they had done with his chicken empire and publicly berated the poor quality of the food under their stewardship.

“It’s a possibility he was thinking of the Colonel,” Daniel Evans told The New York Times after the deal went sour.

Whether or not Sanders really was the culprit is still a mystery.

According to Steve Evans, it was Beatrice that wanted out, drafting documents they knew Bob Evans would never sign since they would prevent his children from starting any competing businesses of their own.

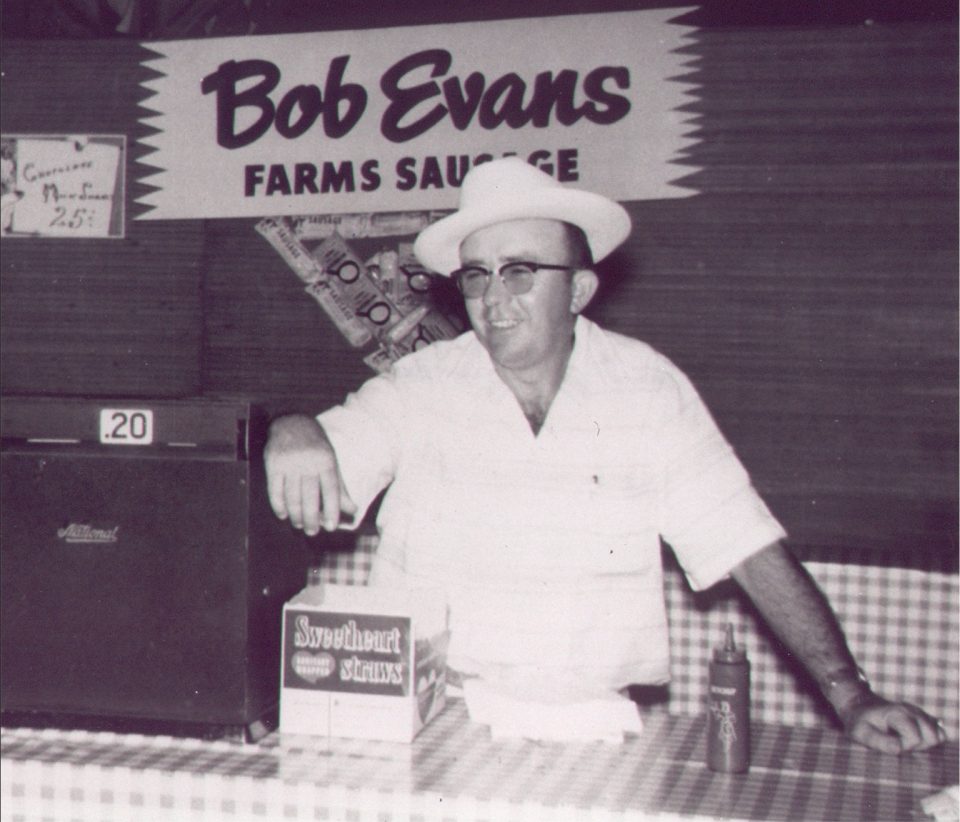

What we do know is that Bob Evans continued to be owned by Bob Evans, at least for a while. And that, with his string tie, Stetson hat and affable Appalachian demeanor, Bob Evans became to Ohio what the Colonel was to Kentucky, both of them inextricably tied to the regions that formed who they were. And while younger people might think they were fictional characters dreamed up by some Madison Avenue agency, they were very much real.

A child of Appalachia

Bob Evans was born Robert Lewis Evans on May 30, 1918, on a farm near Sugar Ridge, Ohio, to Stanley Lewis Evans – a cattleman who owned a successful chain of grocery stores – and Elizabeth Lewis Evans. His grandfather had immigrated to Ohio from Wales to work in the coal mines of Southeastern Ohio. And when Bob Evans was 5 years old, he and his family moved to Gallipolis, where he grew up working for his father, delivering feed and chickens to farmers. Bob Evans was a man of Gallia County in every way. A strong work ethic, a commitment to giving back to those less fortunate. The rolling hills and the community that surrounded him were his everything. Even when he’d made it big, he never wanted to leave it.

In the summer of 1940, Evans borrowed his grandfather’s car and drove to Covington, Virginia, to elope with Jewell Waters, whom he’d first met in high school. “When they walked out of the Methodist chapel, he gave Mom his wallet and said, ‘Here, honey. It’s all yours,’” Steve Evans told me. He estimates there was about $100 in it, his entire life’s savings.

Bob and Jewell settled on a farm in Rio Grande, where they raised their six children (three boys, three girls) in a farmhouse formerly known as the Homestead Inn, a popular stop for stagecoach passengers looking for a good meal in the early 1800s.

After returning home from his service in World War II, Bob and Jewell decided to give it a go in the restaurant business. Along with a man named Herb Bush, they opened a 12-stool diner called the Terminal Steak House, on Route 35, in 1946.

The diner was located in Gallia County, right next to a truck terminal on the Ohio-West Virginia border. It was a smart location, one that provided plenty of customers. The growth of America’s burgeoning automobile business had a lot to do with it, according to Steve Evans. “There was a law back in those days that you couldn’t double stack cars on car carriers,” he said. “So Route 35 had all these cars going south out of Detroit.”

The Terminal Steak House would eventually change its name to The Bob Evans Steak House and remain open for almost a quarter century, closing only on Christmas and Thanksgiving. And it was probably the most family-friendly truck stop in Ohio. “Back in those days, restaurants up and down the Ohio River were mostly bars that sold sandwiches and beer,” Steve Evans said. “Not family oriented. But Dad refused to sell alcohol.” A sign outside read, “No beer, just fine food.”

The sausage king of Gallia County

As the story goes, Bob Evans started making his own sausage because he couldn’t find sausage good enough to serve at his steakhouse. This might sound strange to anyone who grew up in Ohio and knows about that little city on the southwestern part of the state known as Porkopolis. But that didn’t mean the sausage was good.

“Premium country sausage didn’t exist before World War II,” Steve Evans told me. Before then, sausage was a byproduct of processing plants.

Bob Evans set about trying to improve the quality of his sausage by using premium cuts of ham and tenderloins, instead of, well, the other stuff. Like his friend Colonel Sanders, he also came up with a secret recipe of spices. “People just flipped for it,” according to Steve Evans. So much so that he started selling it in tubs so customers could take several pounds of it with them on the road.

Evans soon began focusing less on the steakhouse and more on the sausage-making business, leaving Bush in charge of the steakhouse. He started selling his product to grocery stores and mom-and-pop restaurants throughout the region, eventually opening a retail outlet near his house in Rio Grande. By 1969, Bob Evans owned three sausage plants in Gallipolis, Xenia and Hillsdale, Michigan, selling to more than 4,000 grocery stores and markets.

In 1962, Bob and Jewell opened a restaurant on their farm called Bob Evans Farms Sausage Shop, a popular breakfast spot known for its sausage biscuit sandwiches. They later opened a second Sausage Shop location in Chillicothe. But it wasn’t until 1968 that Bob Evans and several family members opened the first Bob Evans Farms family restaurant in Chillicothe, Ohio. By then, the persona Bob Evans created was as popular as his sausage and even spawned some imitators.

– ??? Restaurants that opened (or closed) in April ??? –

A couple of years before Bob Evans died in 2007, Steve Evans joined him and Jewell on a drive to Nashville to visit the retired president of Jimmy Dean sausage. (“They all knew each other and were good buddies,” says Steve Evans.) On the way, they stopped off at a Bob Evans location in Bowling Green, Kentucky, for lunch. Always eager to meet his customers, Bob Evans introduced himself to some of them, one of whom grew irate, accusing him of lying.

“I know Bob Evans and you’re not him!” she screamed. Furious, Bob Evans approached a manager, who told him there was another man who came in all the time with a string tie saying he was Bob Evans.

“The whole staff thought dad was a fake,” said Steve Evans.

The Joe Burrow of his day

Despite all of his success, Bob Evans’ lifelong attempts to bring attention to Southeast Ohio made him the Joe Burrow of his day, said Cara Dingus Brook, president and CEO of the Foundation for Appalachian Ohio, whose mission is to create opportunities for Appalachian Ohio’s communities through philanthropy. Bob Evans was the first honoree of the foundation’s inaugural I’m a Child of Appalachia campaign in 2005. The campaign uses success stories like Bob Evans’ to promote investment in the region and increase access to college education.

“Bob had a real love for our region,” Dingus Brook told me. “He really prioritized education. He knew our kids had the same potential as kids everywhere, they just didn’t have the same opportunities.”

Bob Evans created scholarships, was a lifetime board member of the Ohio 4-H Foundation and campaigned heavily to bring more (and better) infrastructure to Southeast Ohio.

Bob Evans was also an eco-revolutionary in his support of wildlife and environmental conservation. In the late 1970s, worried about the fate of mustang ponies in the southwest, he led a rescue party to Utah and New Mexico to round up 25 ponies that he took back to Rio Grande. He also turned part of his farm into a wildlife refuge, planting more than 150,000 berry- and fruit-bearing trees to attract birds, animals and insects.

“He had great success and had a lot of good people helping him, all from Appalachia,” said Steve Evans. “(Bob and Jewell) were both children of the Great Depression. They saw the hard side of life early on and that formed who they were.”

What remains of the Bob Evans empire

While Bob Evans Farms took a major hit on its stock market price after the Beatrice deal fell through, it quickly recovered. By 1986, it had grown from around 61 stores to 150. The restaurant now has approximately 500 locations. When Golden Gate acquired Bob Evans in 2017, it cost them $565 million. In 2018, when the Bob Evans wholesale food division was sold to Post Holdings Inc., it went for a whopping $1.5 billion.

In the years since the sale, Steve Evans has reentered the sausage business by launching Steve Evans Sausage, a country sausage that uses a recipe his father once gave to him, written in pencil, one he says better reflects the sausage used at that little 12-stool steakhouse on Route 35. You can find it at Dorothy Lane Market, or order it online at bringthefarmtoyourkitchen.com.

The Rio Grande farm is now a museum and event center that hosts the popular Bob Evans Farm Festival, as well as many other events.

As far as Bob Evans restaurants go, it seems like things are in flux. Just last year, Bloomberg reported that Golden Gate was looking to sell it off for $600 million. Nothing’s happened so far, but it’s anyone’s guess what the future holds.

In the meantime, I think Bob Evans is a restaurant that’s worthy of our appreciation. Sure, it’s a chain, but it can feel as local as any restaurant I’ve ever visited. Lives play out here, widows weep, old men look for solace in a plate of sausage and eggs and a waitress named Erin will offer you a hot cup of coffee before you even have to ask.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: How Bob Evans became to Ohio what Colonel Sanders was to Kentucky