Bob Neuwirth, Folk Singer-Songwriter Who Had Profound Impact on Bob Dylan, Dead at 82

One day in 1970, a young Patti Smith was sitting in the lobby of the Chelsea Hotel in New York, working on her poetry, when a familiar-looking figure approached her. “He came up to me and asked me if I was a poet,” she tells Rolling Stone of the figure in trademark dark glasses she immediately recognized from a Bob Dylan documentary. “I knew exactly who he was. He looked like he’d stepped out of Don’t Look Back, which I’d seen about 100 times. He said, ‘Let me see what you’re writing.’ He started reading and he was one of the first people who looked at my work and took it seriously. He said, ‘You should be writing songs.’”

The figure was Bob Neuwirth, the folk singer-songwriter and painter who influenced or impacted on a wide range of artists, including Smith, Bob Dylan, and Janis Joplin. Neuwirth died Wednesday at age 82 in Santa Monica, California, according to his partner, Paula Batson, who confirmed the death to Rolling Stone.

More from Rolling Stone

“On Wednesday evening in Santa Monica, Bob Neuwirth’s big heart gave out,” Neuwirth’s family said in a statement. “Bob was an artist throughout every cell of his body and he loved to encourage others to make art themselves. He was a painter, songwriter, producer and recording artist whose body of work is loved and respected. For over 60 years, Bob was at the epicenter of cultural moments from Woodstock, to Paris, Don’t Look Back to Monterey Pop, Rolling Thunder to Nashville and Havana. He was a generous instigator who often produced and made things happen anonymously. The art is what mattered to him, not the credit. He was an artist, a mentor and a supporter to many. He will be missed by all who love him.”

Related video: Naomi Judd's cause of death revealed

Throughout his multi-decade career, Neuwirth moved back and forth between the worlds of music and art, largely and happily under the radar, although his connections with classic rock made him a legend. Dylan fans remember him for his caustic cameos in Don’t Look Back, director D.A. Pennebaker’s movie of Dylan’s 1965 U.K. tour, as well as Neuwirth’s appearances in the 1975 Rolling Thunder Revue tour. Joplin fans recognize him by way of her a cappella classic “Mercedes Benz,” which the two co-wrote with poet Michael McClure. In the private-collector art world, Neuwirth was renowned for exhibitions of his paintings, and Velvet Underground diehards recall his Nineties work with John Cale. Neuwirth also introduced Joplin to “Me and Bobby McGee,” written by his friend Kris Kristofferson; Joplin recorded the song just days before her 1970 death.

“When you’re around people like that, you’re not driven to be a musician,” Neuwirth said in 1989 of his collaborations. “I had other outlets. I was a painter, so it never occurred to me to do any of those other things.”

“He was good at everything,” says Smith. “He was a great songwriter. A moving singer. A really fine painter. He had so much magnetism; you couldn’t not be drawn to him. But it wasn’t because he was aggressive. He just wasn’t the kind of person who pushed own agenda on a situation.”

Born in Akron, Ohio, on June 20, 1939, Neuwirth first attended Ohio University before moving to Boston in 1959 to attend the School of the Museum of Fine Art on an arts scholarship. After a side trip to Paris, he returned to Boston, working in an art supply store and learning to play banjo and guitar, which led him to become part of the early Sixties Cambridge folk scene. “Painting is how I got into folk music, in a way,” he said in 1989. “I sort of put myself through art school as a folk singer. It was always my secondary art, and my part-time job.”

Neuwirth began visiting the similar scene developing in New York’s Greenwich Village (partly, he once joked, because the weed was more readily available). At one point in a club there, he met Dylan, with whom he shared a caustic, cutting sense of humor and hipster persona. “Right from the start, you could tell that Neuwirth had a taste for provocation and that nothing was going to restrict his freedom,” Dylan wrote in Chronicles Volume 1. “He was in a mad revolt against something. You had to brace yourself when you talked to him.” Dylan also referred to Neuwirth as “a bulldog.”

Eventually, Neuwirth became part of Dylan’s tight inner circle, hanging out at bars like the Kettle of Fish in the Village and trading barbs with whoever was in sight. As one singer who played with Dylan told Rolling Stone in 1972, “Neuwirth was a scene maker, a very strong cat. When he got to New York in 1964, he started hanging around Dylan. And Dylan started to change at that time. Part of it was Neuwirth, he was a real strong influence on Dylan. Neuwirth had a negative attitude, stressing pride and ego, sort of saying, ‘Hold your head high, man, don’t take shit, just take over the scene.’ He was the kind of cat who could influence others, work on their egos and support those egos. His whole negative attitude fell in perfectly with what Dylan was feeling.”

Neuwirth moved to L.A. soon after, where he remained for most of his life afterwards. In 1974, after years playing clubs, he finally released a record of his own, Bob Neuwirth, on David Geffen’s Asylum label. The album – which set Neuwirth’s craggy voice to freewheeling, sometimes boozy honky-tonk – wasn’t a commercial hit. But it was a cult favorite, and plans to reissue it were in the works when Neuwirth died. (The project is currently scheduled for release next year.)

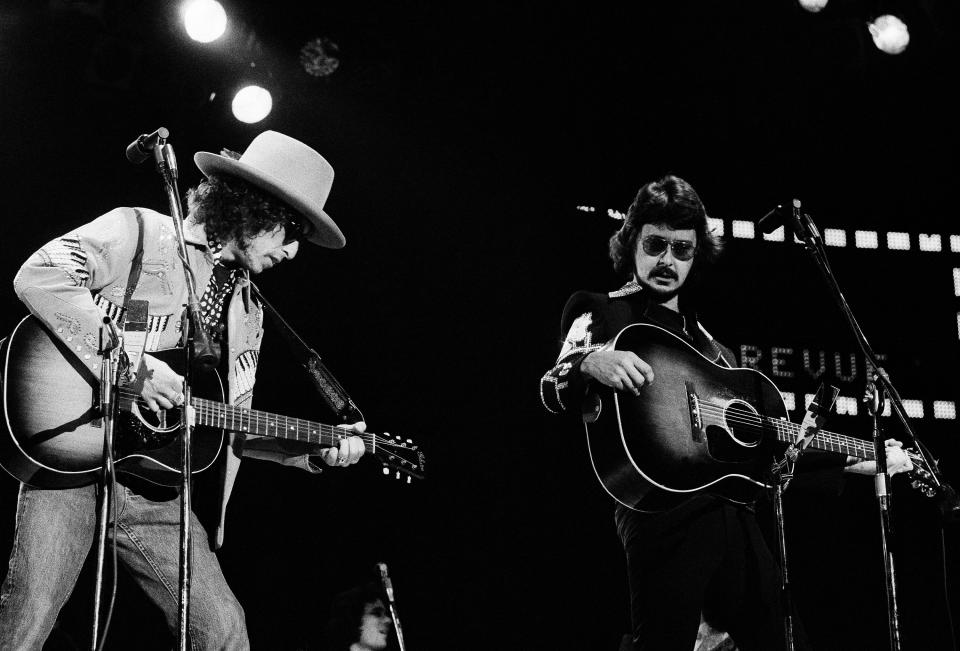

Larry Bercow

In addition to Don’t Look Back, Neuwrith also co-starred in Dylan’s experimental 1978 film Renaldo and Clara. That film also featured many of the artists in Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, an ensemble Neuwirth is credited with helping to assemble. (Neuwirth’s 1975 shows at the Other End in the Village became a gathering point for many of the participants on that tour.)

For Joan Baez, who met Neuwirth on the Cambridge folk scene, Neuwirth could be a stabilizing figure when she found herself out of sorts in Dylan’s world, starting with the tour immortalized in Don’t Look Back. “When we were on that tour, I was feeling horrible and Bob [Neuwirth] wanted me to go home,” he says. “He said, ‘It’s not going to get any better.’ And it didn’t. But Neuwirth was right.” A decade later, during the Dylan-led Rolling Thunder shows, Baez was feeling similarly out of sorts. “I felt slighted again, which is how I spent much of my time with Dylan,” she says. “I had taken to my bed in my hotel and Neuwirth came in and started acting silly and opened the window and shouted, ‘She’s going to live!’ He was just one of those people who could make you laugh.”

The painting work he had started in the early Sixties continued. Early in his career, he produced what were called “quirky hybrids of Cubism and Surrealism.” Later, he concentrated on wall works that incorporated painting and sculpture. A major exhibit of his work, Overs & Unders: Paintings by Bob Neuwirth: 1964 – 2009, took place in Los Angeles in 2011.

Although his music career was never his priority, Neuwirth dipped back into that part of his life intermittently. Starting with 1989’s beautifully spare Back to the Front, he resumed making occasional, wry and often stark country-folk records. With John Cale, whom he’d met during their time hanging out at Andy Warhol’s Factory in the Sixties, he made 1994’s Last Day on Earth, which Neuwirth described as “an abstract Prairie Home Companion.” In 1995, Mercedes Benz licensed Joplin’s song for a high-profile commercial. “I wonder what took them so long,” Neuwirth cracked at the time. (Of the song, which was quickly written between sets of a Joplin show, he said, “It was a throwaway, a fluke. I wouldn’t call it songwriting.”) Neuwirth also produced two albums for Texas singer-songwriter Vince Bell.

In 2004, Neuwirth served as emcee of Great High Mountain, a bluegrass and Americana tour inspired by the success of O Brother, Where Art Thou? and featuring Alison Krauss, Ralph Stanley and others. In recent years, he also participated in tribute concerts to Randy Newman and the late folklorist Harry Smith, as well as a 2018 New York concert recreating Dylan’s 1963 show at Town Hall. The latter was especially noteworthy since Neuwirth normally distanced himself from his Dylan associations, rarely giving interviews about that period in his life.

“Like Keruoac had immortalized Neal Cassady in On the Road, someone should have immortalized Neuwrith,” Dylan wrote. “He was that kind of character … With his tongue, he ripped and slashed and could make anybody uneasy, also could talk his way out of anything. Nobody knew what to make of him. If there was ever a renaissance man leaping in and out of things, he would have to be it.”

For Smith, the cover of Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited — which shows Neuwirth, but only as a pants-wearer standing behind Dylan — spoke to his understated but important role in the culture. “That’s him in a nutshell,” she says. “He stays in the background. But he’s there, and his presence is always strong.”

Additional reporting by Daniel Kreps

Best of Rolling Stone