"The Chair" Accurately Portrayed How Women Of Color Dress In Academia

Hi, I'm Rani, and I’ve been a professor of Asian American literature and writing for the past 18 years. I recently watched Netflix’s new show The Chair, starring the amazingly talented Sandra Oh.

Not only did all the politics of an old, white English department ring true, but I was struck by how the women in the show were dressed — particularly the BIPOC women.

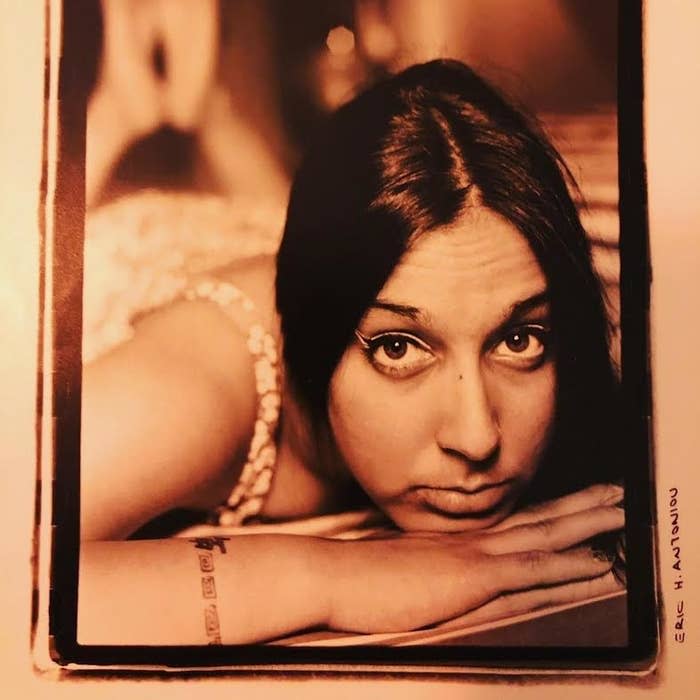

I went to grad school at UC Berkeley in the early 2000s to receive my PhD in Ethnic Studies. While I was there, I was flamboyant and unapologetically obsessed with fashion.

I wore vintage A-line dresses lined with plush petticoats and wrapped rhinestones around my wrists. My earrings were always large and loud. My makeup was bold. An array of eyeshadows in primary colors sat on my dresser waiting to be applied, and my lips were always masked with maroon, red, gold, and pink.

Five years into my program, I received a predoctoral position at a small, elite, liberal arts college in the Northeast. I carried my books, bright makeup, and my closet full of vintage clothes with me.

I was one of a few women of color in the department. One was on a tenure track line. She dressed professionally, aware of the boundaries of the English department filled with mostly men, and mostly white men, and how she dressed played into how she fit in — slacks and crew neck sweaters, skirts right above the knee. Being on a tenure track line as a woman of color is the most precarious of positions, and I didn’t yet realize how much clothing played into that narrative.

The Chair is also acutely aware of how a woman, particularly a woman of color, needs to dress in order to survive the brutal world of academia.

Sandra Oh’s character, Ji-Yoon, never wears any shirts that go below her neckline, her sweaters are buttoned all the way to her neck, and her shirts are all stand-up collars and turtlenecks.

Most of her clothing is a series of gray, brown, black, and tweed — nothing is patterned.

There is only one scene in which Oh’s clothing deviates. During a faculty party, she wears a red shirt, but even then it is smock necked and long sleeved.

Not once do I remember her showing any skin at all.

During the same party, the only Black woman in the department, Yaz, played by the superb Nana Mensah (who is tenure track, not tenured) is wearing a multi-patterned V-neck dress — only a tiny fraction of her skin is exposed.

As she sits by one of the white male faculty members who will determine whether she gets tenure or not, he remarks on her outfit, “Well that’s a very nice outfit you have on; it looks like three different dresses that you put together in a very good way.” She uncomfortably replies, “Thank you.”

As a Black woman, she is hyper-visible and always commented on — always on display for men to judge, condemn, and desire.

In another scene, the only white woman in the department, Joan (Holland Taylor), goes to the Title IX office to complain that she is the only faculty member forced to move her office into a basement with no Wi-Fi (what she calls a “subterranean shithole”), while all the other men in the department are not moved.

However, she later encounters a much younger woman of color who is wearing shorts. Joan is frustrated by the idea that a young woman who hasn’t experienced the years of sexism she has will decide whether she has a case.

Joan comments on her clothes, exclaiming, “Everyone can see your fanny!” Her comment is profoundly sexist, yes, but is it also proof that women in academia have had to hide behind layers of clothing for decades and still do?

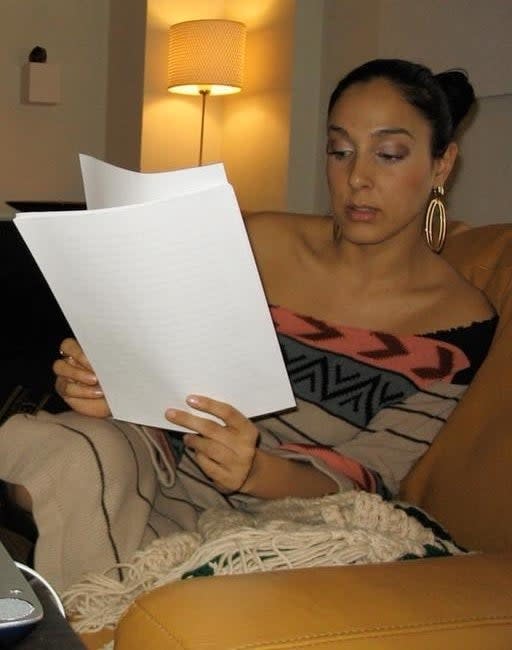

While watching the show, I recalled the ways in which I was trained to subdue my look and annihilate any sense of boldness.

When I went on the job market one year, the white male chair of the small liberal arts department wrote a letter of recommendation for me. Someone I knew was on the hiring committee for a job and told me I had what is known as a “poison letter,” in which the recommender, in a coded fashion, warns that you are problematic. In the chair’s letter, he wrote, “Despite her flamboyant clothing, she does a good job.” I wondered if men ever had their clothes commented on in recommendation letters, as if how I dressed determined if I was smart or a good teacher or capable of intelligent scholarship.

As I searched for a tenure track job for eight years, many people told me that the reason I didn’t do well in interviews was that I was too daring in my dress. If I dressed the way I wanted, people wouldn’t listen to me; they would only look at me. My sexuality and body would outshine my intellect.

I began to dress drab, didn’t show any skin, and only wore black and brown. I didn’t wear makeup and pulled my hair into a tight bun. One year, one of my mentors, who was 70 years old, told me I had to dress as she did and let me borrow one of her suits. I still didn’t get a job.

The Chair gets many things about academia right, as multiple articles have acutely noted.