The curious story of Free's debut album

At the time when the sunshine 60s were about to give way to the uncertain 70s, the Island Records label was seen by rock fans as a trademark of quality. The record company once synonymous with reggae had seemingly cornered the market in home-grown progressive artistes: bands like King Crimson, Traffic, Spooky Tooth, Mott The Hoople. The ‘softer’ side of rock, from Fairport Convention, Nick Drake and even Cat Stevens, also enjoyed a certain credibility by association with the stark yet stylish pink label.

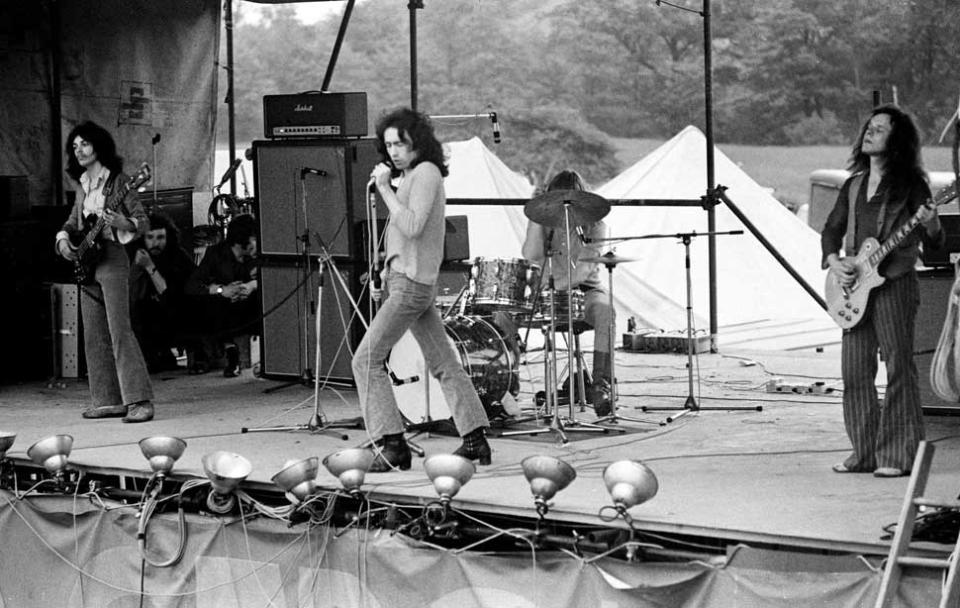

Free were part of the Island stable, yet they were also a breed apart. Younger than most – bassist Andy Fraser was a precocious 16 – they sported wild leonine manes of hair and a couldn’t-care-less attitude honed on the rough-and-ready UK circuit of blues clubs and ballrooms. Any promoter trying to pay a penny less than the fee the band’s contract stipulated would face a four-square, eight-fist protest. That togetherness also came across in Free’s music.

Many people’s introduction to Free was when they heard I’m A Mover while listening to the Island sampler You Can All Join In. The compilation album (which, unexpectedly and remarkably, made the Top 20 in June 69) was a favourite among impecunious ‘heads’ who wanted a blast of rock at a bargain price.

But Tons Of Sobs, Free’s debut album released in 1968, was well worth saving up for. No UK single was released from it, and that was hardly a surprise – I’m A Mover, performed at a slow, steady yet relentless pace, exuded a menace that had no place on Top Of The Pops. Not until All Right Now in summer 1970 would Free be recognised by the fickle chart audience. With Led Zeppelin’s career also taking off, this period was developing into a prime-time one for album bands.

Most first albums represent their performers’ stage act, and …Sobs was no exception. But the stage-hardened Free (they had played five or six nights a week in their short, six-month existence) found the atmosphere of Morgan Studios in Willesden, north-west London, not conducive to producing their best work.

Even though blues-rock supergroup Humble Pie would knock off their first two albums there a matter of months later, Free singer Paul Rodgers couldn’t settle to the task.

“They put vocalists in little, airless cupboards in those days,” he recalled. “I’d turn the lights down, close my eyes and imagine I was on stage. It was the only way I could get a feel for it.”

At least an air of informality was encouraged by maverick producer Guy Stevens who, in an attempt to capture Free’s live élan, took away the soundproof baffles so the band could see each other. The Tons Of Sobs sessions was one of the first jobs for young engineer Andy Johns (younger brother of famed producer Glyn, and of a similar young age to Free), who did his best to ensure smooth running on the technical side.

Talking exclusively to Classic Rock, drummer Simon Kirke confirms Stevens’ pivotal role: “Guy was this nutty catalyst, seemingly full of enthusiasm for everything – which, I eventually found out, masked his underlying depression. He was instrumental in getting our first album together. ‘Just go in there and do your normal set.’ Those were his exact words. The whole album was cut in two days, with a couple more to mix. He was very endearing… when he wasn’t hurling himself around the studio spilling wine everywhere!”

The longest track by far, at a shade over eight minutes, was a cover of Howlin’ Wolf’s Goin’ Down Slow. And the best compliment that can be paid to it is that it doesn’t outstay its welcome. Research by Free biographer David Clayton has ascertained that the song, along with Wild Indian Woman, was attempted once and once only, on October 22, 1968. An eight-minute first take is very impressive.

“We were a blues band, plain and simple,” Kirke says, noting that Goin’ Down Slow “gave the two Pauls [Rodgers and guitarist Kossoff] acres of ground and time to stretch themselves”.

(The tracks done at Morgan Studios were not actually Free’s first professional recordings; those had been made three months earlier, when the BBC – in the shape of Radio One DJ John Peel – invited them to record four songs. Three of those tracks recorded by the BBC were among the eight bonus tracks included on the CD remaster of Tons Of Sobs in 2000.)

Guy Stevens’ decision to book-end Tons Of Sobs with Rodgers’s acoustic Over The Green Hills by cutting it in half – ‘part one’ opening the album and ‘part two’ closing it – didn’t appear to upset its writer. (Stevens would use a similar ploy on Mott The Hoople’s debut album.) It also somehow set the tone for the album by contrasting the soulful, introverted side of Free’s music that would emerge over time with the electric blues they were playing then. (Over The Green Hills has its missing middle verse reinstated on the box set Songs Of Yesterday – a must for any Free fan.)

The swaggering likes of Wild Indian Woman, Sweet Tooth and especially Walk In My Shadow formed the template that David Coverdale would use extensively and successfully almost a decade later – interestingly, with the assistance of Micky Moody, an early bandmate of Rodgers’ in a band called The Roadrunners. New Musical Express described the effect Free obtained as ‘a heavy, penetrating sound so thick you could cut it with a knife’. And on this evidence few would argue.

Although Rodgers would later play piano while with Bad Company, Free’s main keyboardists were Andy Fraser and then John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick. For Tons Of Sobs, though, outside assistance on keyboards came in the shape of Steve Miller (from the band British Delivery, and not to be confused with the American bluesman of the same name). He ran a blues club in Bishop’s Stortford, Essex, and was invited to attend the session by Rodgers, who rated him “an exceptional player, we were good mates”. Miller merrily bashed the ivories as if in a bar band (his album credit reads ‘piano thumping’), and also contributed occasional organ.

It’s the interplay between Rodgers’ vocals and Kossoff’s guitar that makes Tons Of Sobs so special. Though Free may have recorded superior material on subsequent albums, it would never be played more passionately. It’s truly amazing to think, given the emotion in their performances, that both of them were aged just 18 at the time.

Originally scheduled to be released in November 1968 (a date perpetuated by many discographies) Tons Of Sobs finally appeared in mid-March 1969. The delay was due to the late addition of what is now recognised as one of the album’s standout tracks. Curiously, The Hunter was not a last-minute composition, but a cover version of a song that was fast becoming a highlight of Free’s live set. Written by Booker T. Jones, it had been recorded by bluesman Albert King.

Free’s version , recorded at a specially convened session a week before Christmas 1968, was included at Guy Stevens’ insistence. Visions Of Hell was the track it replaced, due to the restrictions of vinyl albums to 20 minutes per side. As ever, Stevens’ ears did not deceive him. Free’s cover of The Hunter strutted and preened like no other song on the album, with Rodgers delivering the (now regarded as somewhat sexist) lyric with gusto and Kossoff sparking fiery clusters of notes from his Gibson Les Paul guitar at every opportunity.

The song would remain their live calling card, even after the success of All Right Now. And while most fans consider the version of The Hunter on Free Live to be the definitive one, this studio take isn’t far behind in terms of swagger.

Simon Kirke disagrees with the view that Free were four angry young men: “I don’t think I was an angry drummer so much as a passionate one… ditto Paul’s singing. True, he can be short-tempered at times, and there is a certain amount of aggression in his singing. But by the same token, playing music is a therapeutic journey.”

The Hunter contains several overdubs: “We just piled it on because we could,” Rodgers admitted, as if to confirm that Free had, at last, got the measure of the studio. Chris Blackwell must have felt that, too – or at least had more faith in Free’s potential than that of Mott The Hoople, who would remain in Guy Stevens’ thrall – and it would be the Island Records boss himself who handled the production on Free’s second, eponymous, album, with Andy Johns remaining as engineer.

In terms of other rock albums, there were plenty of yardsticks for young pretenders Free to measure themselves against – Cream’s debut Fresh Cream and the Jeff Beck Group’s Truth, for starters. Kossoff was a long-time Eric Clapton fan. But when Free played their first American tour, supporting Clapton’s post-Cream band Blind Faith, it was Eric who asked for advice, quizzing the teenager as to exactly how he got his vibrato. Tons Of Sobs was clearly what the elder player had been grooving to.

Kirke reveals what a thrill that must have been for his young bandmate, but says: “I don’t think we really tried to emulate anyone, but Koss and me were huge Cream/Clapton fans. Hendrix, too… After a while we all became fans of The Band, but we never really looked up to Zep… I became an admirer of them later, in my Bad Company days.”

With the majority of the tracks brought along by Rodgers, the Tons Of Sobs album nevertheless marked the beginning of the Fraser-Rodgers songwriting partnership that would eventually yield many future classics.

“Paul was strongest in the lyrics,” Fraser would recall. “His songs were very vocal-based… mine started with arrangements.”

Rodgers’ Sweet Tooth, the album’s final track before part two of Over The Green Hills, showed a lyrical progression that Fraser puts down to a Beatles influence. Unusually, Free never performed it outside of the studio.

The pair profited from a piece of bad luck when illness laid Rodgers low for a couple of months. Fraser’s family took the ailing vocalist in, and his period spent sleeping on the sofa allowed him and Fraser to write the likes of Mourning Sad Morning, I’ll Be Creepin’ (both of which appeared on the band’s second album) and what would be the title track of their third album, Fire And Water.

The songwriting partnership of Rodgers and Fraser certainly proved fruitful in creative and commercial terms, but it also potentially sidelined Kirke and Kossoff. Kirke’s happy-go-lucky nature enabled him ride out the storm, success undoubtedly sweetening the pill, but for Koss, whose live showmanship had done so much to build the band’s following, diminution of his role was hard to take.

“In terms of Koss’s playing, Tons Of Sobs was his most free-flowing,” Kirke agrees. “After all, it was a mirror image of our live set, so it could be said that subsequent albums required a more toned-down approach to the guitar… Quite honestly, I think he was more a blues guitarist than anything else, and when Paul and Andy started coming up with songs which weren’t in that mould Koss got a little bit uncomfortable. He wasn’t a great rhythm player, but he sure made up for it in his solos.”

The drummer and guitarist had even talked about forming their own band (which became reality as Kossoff, Kirke, Tetsu & Rabbit in 1971), and Kossoff had also auditioned for sometime Island labelmates Jethro Tull after Mick Abrahams left that band. Kossoff is also said to have tried out for the Rolling Stones following Brian Jones’ death, competing with Mick Taylor for the gig.

Given Kossoff’s subsequent debilitating drug problems, it’s tempting to see the descent starting here. But instead of following that path, why not rejoice in the playing of a man who had so much feeling that it hurt?

British blues godfather Alexis Korner, the man who christened Free, got it right: “One of the things that impressed me most about him, as a very young player, was that he knew when not to play. It made him exciting.” A fledgling American guitarist called Tommy Bolin clearly agreed, and included I’m A Mover and Walk In My Shadow in the repertoire of his early group Energy.

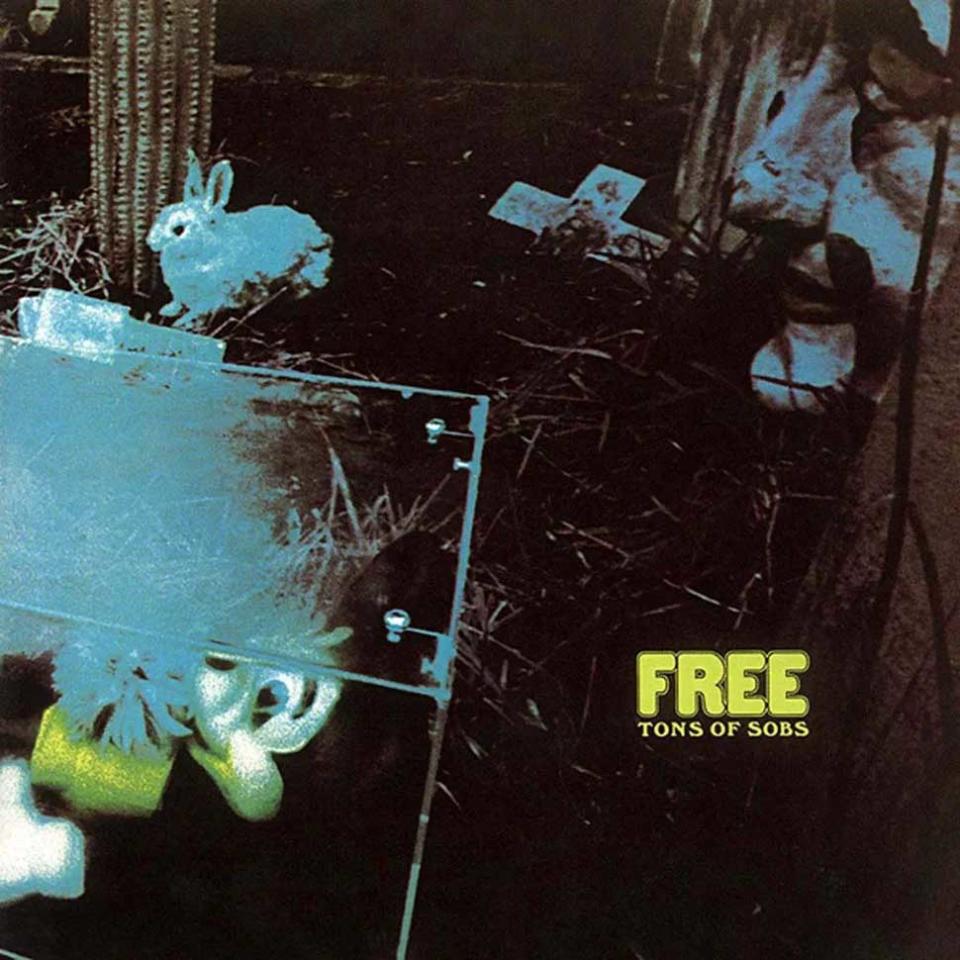

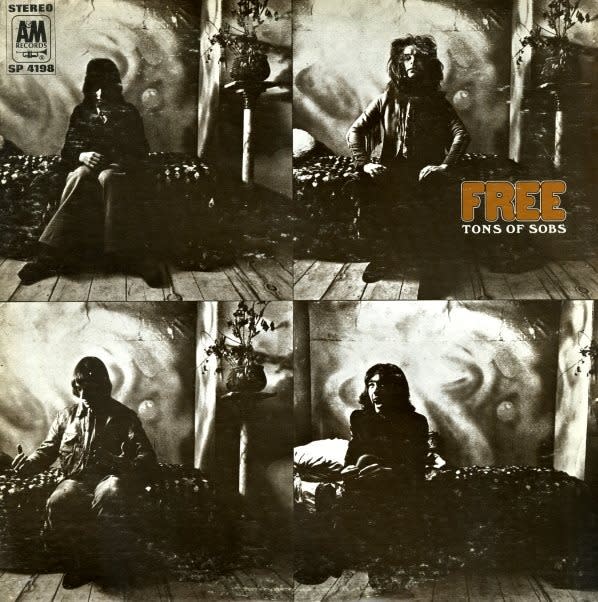

It wasn’t hard to see how a young rock fan could fall for Free. The gloomy gatefold sleeve for Tons Of Sobs, shot in a graveyard, had all the dark imagery Black Sabbath would soon try to trademark, while the gloomy Moonshine (Paul Kossoff’s first composition for the band, with lyrics by Rodgers) could have sat easily on Sabbath’s first album. The song is also said to have influenced the …Sobs cover, with its lines: ‘Sitting in a graveyard, praying for the dawn/Leaning on my tombstone ’til the night has gone.’

You can’t fully appreciate the album cover concept from the CD-sized version, but suffice to say the tinted effect underlines the ‘gothic nightmare’ idea of the lyric. The sleeve’s photographer, Mike Sida, was a friend of Guy Stevens. But since both men are no longer with us, the deeper meaning behind the image of a bendy toy in a transparent plastic coffin surrounded by broken stone crosses will have to remain conjecture.

The band were present at the photo shoot, even though they didn’t feature themselves. “This was the 60s, and anything went – all under the banner of artistic expression,” Simon Kirke laughs, amused at the memory. “I just remember this cold, damp day in Barnes cemetery, lugging this plexiglas coffin around with Mickey Mouse and other dolls and artefacts and just wondering what the fuck we were doing there, and couldn’t we just all slope off to the pub? But it is still one of the most recognisable album covers around.”

The packaging was curious enough for the band’s American label, A&M, to junk it completely in favour of shrinking it to a single sleeve, turning it outside in, and featuring individual pictures of the band members on the front and a group shot on the back. One reason for that decision could be the silhouette of the previously mentioned (and presumably deceased) Mickey Mouse at the bottom right of the front cover – a lawsuit from Disney would not have been the best way in which to kick off a young band’s US career.

The Americans might not have got the title, either. ‘Sobs’ was actually ‘Sovs’, or sovereigns, an old-fashioned unit of currency, so Tons Of Sobs translated to ‘loads of money’. But Paul Rodgers accepted the title, which came from the same ideas book from which Stevens had pulled Heavy Metal Kids (at one time Free’s potential name) and Mott The Hoople “because it had a blues connotation… we could live with that”.

Cumulative sales figures for Tons Of Sobs over the past 35 years are impossible to find. Universal, Island’s current parent company, offer CD sales of 12,500, but no record of its vinyl-era performance. Certainly it’s unlikely to approach chart highlight albums Fire And Water (1970) and The Free Story (1974), both of which reached UK No.2, but it will long since have paid back its modest studio budget of £800 (£1,500 including artwork and other costs). Recorded in those few October days in 1968, with other bands waiting at the studio door and gigs to be fitted in, it has a primitive, enduring appeal and still sounds superb today.

Many bands have drunk deep from its well, as Simon Kirke agrees: “The Black Crowes, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Foreigner… Bono said he loved us.” Kirke recalls seeing U2 when they were a fledgling band and thinking they were “a deadringer for Free in terms of a stripped-down sound and passion”.

Kirke concludes that Tons Of Sobs, for all its faults, is “a very underrated album. And not bad for a band whose average age was 17!”

For Paul Rodgers, who, according to former north-east bandmate Micky Moody, had taken up a window-cleaner’s leather and ladder when times were tough, Tons Of Sobs was nothing less than a vindication.

“It brought it home to me when I brought an acetate [test pressing] to Middlesbrough under my arm,” Rodgers remembered. “I was coming home on the train, and then I got a perspective of it: ‘Here I am. I’ve been to London, formed a band and I’ve got the record here to prove it!’.”

This was published in Classic Rock issue 62, published in January 2004