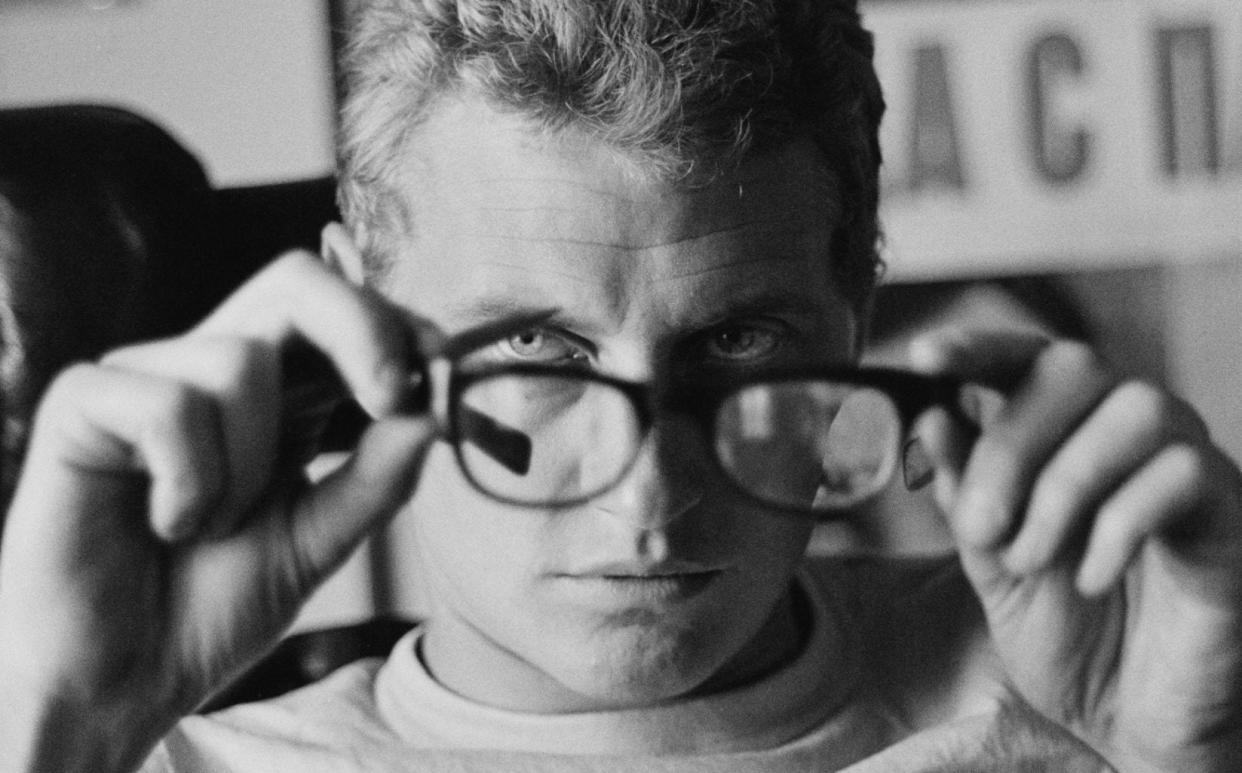

Derek Boshier, Pop artist who designed for Bowie and passed a joint to Princess Margaret

Derek Boshier, the artist, who has died aged 87, was one of the founders of British Pop Art in the 1960s, before becoming well-known for his collaborations with David Bowie and the Clash.

At the 1962 Young Contemporaries exhibition that launched British Pop Art into the public consciousness, Boshier’s work was shown alongside that of his fellow Royal College of Art students David Hockney, RB Kitaj and Allen Jones. The movement’s preoccupation with consumerism and American cultural dominance was exemplified by Boshier’s painting England’s Glory, depicting a US flag slicking over a box of England’s Glory matches.

Ken Russell’s trippy documentary Pop Goes the Easel, in the BBC’s Monitor strand, soon brought the 24-year-old Boshier to national attention. It profiled four Pop artists – the others were Peter Blake, Peter Phillips and Pauline Boty – and captured their youthful energy, showing them larking about on fairground dodgems and dancing the Twist.

The film also showed Boshier perusing cereal packets as he explained that one of his most famous paintings, Special K – one of dozens of his works that played with the Kellogg’s logo – was a commentary on “the infiltration of the American way of life”. “The Englishman… starts with America at the breakfast table, with cornflakes.”

Among his other early paintings of note were Man Playing Snooker and Thinking of Other Things, depicting the inside of a man’s head stuffed with commercial logos, and I Wonder What My Heroes Think of the Space Race, featuring Lord Nelson, Abraham Lincoln and Buddy Holly. Six decades later that painting was reported to be among those selected from the Government Art Collection by the prime minister Boris Johnson to adorn his flat in Downing Street, not an honour likely to please the perennially radical Boshier.

He held his first solo exhibition, Image in Revolt, at the Grabowski Gallery in 1962, and found himself at the centre of Swinging London: his rangy figure could often be seen dancing with Pauline Boty on the quintessentially 1960s pop music programme Ready Steady Go! He got to know Lord Snowdon, and recalled attending a Kensington Palace soirée at which a marijuana joint was handed to him; he passed it straight on to Princess Margaret, insisting: “Please, Royals first.”

Unlike Hockney or Blake, however, Boshier had no flair for self-publicity, and did not capitalise on his moment in the spotlight. Instead, he decided to live in India for a year; on his return he found himself already out of fashion. He had no regrets: “I’ve been much more interested in life than in art,” he once observed.

He became an instructor at the Central School of Art and Design, where one of his pupils was John Mellor, later to become Joe Strummer, frontman of the Clash. In 1978 Boshier was commissioned to produce the songbook that accompanied the release of the Clash’s second album, Give ’Em Enough Rope: the drawings and paintings that illustrated the lyrics included a depiction of policemen in evening gowns to accompany Julie’s Been Working for the Drug Squad.

In 1979 the photographer Brian Duffy told Boshier that he had a friend who wanted to meet him: “The way he phrased it, I thought it was a blind date.” In fact when he arrived at Duffy’s studio, it turned out to be David Bowie.

Bowie had become fascinated by the figure of a man falling through space, derived from William Blake, which had become a motif in Boshier’s oeuvre (“It’s… a symbol of liberty, of countering gravity, of freedom,” Boshier once explained). Boshier designed a cover for Bowie’s album Lodger, depicting the singer falling; the effect was achieved by artfully arranging Bowie on a trestle table.

Boshier also designed the cover for Bowie’s 1983 album Let’s Dance, which featured one of his paintings projected on to Bowie’s naked torso, and provided set designs for the Serious Moonlight tour, although as Bowie encouraged him to “forget about practicalities”, the set builders were unable to realise most of them.

Shortly before he died in 2016, Bowie wrote to Boshier to reiterate his admiration for him, telling him: “Your work cascades down the generations.”

Derek Boshier was born in Portsmouth on June 19 1937, the son of a Royal Navy rating who later became a caretaker at Sherborne School for Girls.

Derek decided to leave school at 16 when a friend’s father offered him a job in his butcher’s shop, until the art master intervened. “He said, ‘Have you ever thought of doing Art?’ I said, ‘What’s Art?’ and he said, ‘It’s what you do on Thursday afternoons.’ I said, ‘Oh, I like that.’ “

He spent three years at Yeovil School of Art in Somerset, and after National Service with the Royal Engineers enrolled at the Royal College of Art in 1959. He remained grateful that he had fallen into pursuing art at a time when “art school opened up the only possibility for working-class kids to get a further education.” In later years he felt that the working-class, non-metropolitan essence of British Pop Art had been under-emphasised by critics and historians.

He became friends with John Lennon and they would discuss art together at the Beatle’s Kensington flat: “Like me, he adored Hieronymus Bosch.” When Lennon, who had never owned a car, declared that he needed one, Boshier sold him his green Triumph Herald convertible for £100 and went home in a taxi.

In the 1970s Boshier moved away from painting for a time to embrace collage, photography and film-making. Much of his work offered jaundiced comment on the advertising and media worlds’ view of artists, including one piece depicting a chimp working at an easel.

He won much acclaim in 1979 as the curator of the Hayward Gallery’s Lives exhibition, controversially exhibiting video art and cartoonists: eliminating the boundaries between “high” and “low” art was one of his abiding concerns.

From 1980 to 1992 Boshier taught at the University of Houston in Texas, where he found himself “revitalised” as a painter and produced a series of ironic works “de-macho-ing” cowboys.

He returned to live in Somerset for a time, stating that he had missed “pavements, landscape and humour”, but found it hard to interest English galleries in his work and eventually took another teaching job at California Institute of the Arts. He was based in Los Angeles for the rest of his life.

He remained close friends with David Hockney, who covered his medical expenses when he was diagnosed with cancer of the tongue in 2006.

In his final decades, Boshier’s reputation revived, with numerous exhibitions around the world; it was a measure of the increasing value of his work that in 2018 a sketch he was working on at Tate Britain was stolen from his easel. In 2016 he was appointed an honorary fellow of his alma mater, the RCA.

Boshier’s later work remained engaged with both politics and popular culture, its inspirations ranging from debates on gun control and police brutality to football, video games and Korean pop music. His film piece I Never Knew the World Was So Beautiful was inspired by his interviews with a woman who was blind from birth before having her sight restored aged 30.

Asked by the Daily Telegraph’s Alastair Smart in 2021 if he was nostalgic for the 1960s, Boshier replied: “Not really, I’m too busy.” But he remained devoted to the memory of Pauline Boty, who had died of cancer in 1966, and paid homage to her in his 2011 painting Pauline Goes Digital.

Derek Boshier is survived by his long-term partner Thelma Gaskell, and by the two daughters of his marriage to the Colombian-American artist Patricia González.

Derek Boshier, born June 19 1937, died September 5 2024