“I didn’t have anything against guitars – I just had this idea in my head of two keyboard players using an array of instruments. Everyone said, ‘It’ll never work.’ Well, they were wrong”: The short life and lasting times of Greenslade

Greenslade’s 70s heyday might have been short, but in 2018 Prog told the story behind this “thinking man’s band” from their controversial choice to disregard guitars, through unlikely tourmates, to what the future might hold.

“I’ll tell you what is really staggering – it’s 47 years since the first Greenslade album and now they are all being re-released across the world,” says Dave Greenslade. “After all this time, we’ll be an overnight success!”

Greenslade were only around for a short time – from autumn 1972 until their last gig at Barbarella’s, Birmingham, in December 1975. The group recorded for a major label, Warner Brothers, and Spyglass Guest (1974) reached No. 34 in the UK album charts. It followed the group’s 1973 debut, Greenslade, and Bedside Manners Are Extra, also 1973, while 1975’s Time And Tide came last.

“I’m very proud of these compositions,” says Greenslade. “I’m lucky to have had a chance to form a band with those guys. We made a great combination. And it was a most unusual band at the time – no guitar and two keyboard players.”

Greenslade had played keyboards in Colosseum and, when they broke up in 1971, he was left with a number of unrecorded pieces, so looked to form a new band. Firstly he recruited Colosseum bass guitarist Tony Reeves, who got in touch with keyboard player and vocalist Dave Lawson, (he’d been in Samurai and Web). Lawson in turn contacted drummer Andy McCulloch, who’d played in Fields and King Crimson.

One can hear some similarities in the music of Greenslade, particularly their debut album, and Colosseum’s side-long Valentyne Suite, which was largely written by the keyboard player – but overall it’s quite different in feel. So had Greenslade any plans as to the sort of music he was going to make in his new group?

“It wasn’t a conscious thing, it was just a development,” he replies. “I never thought, ‘Come on, lads, let’s form a prog rock band!’ It never crossed my mind. So very quickly the four of us got together and started rehearsing and writing – I was writing a lot of stuff. We had great fun, and we got signed up to management.”

The fact that Greenslade had no guitarist and two keyboard players gave them a certain hip cachet at the time; but to some, such a line-up appeared to be ill-advised. “When I told my chums and musical colleagues that I was going to form a band without a guitar – I didn’t have anything against guitars, I just had this idea in my head of two keyboard players using an array of instruments – everyone said, ‘It’ll never work, Dave.’ Well, they were wrong.”

Clem Clempson, formerly of Colosseum and then in Humble Pie, did play guitar on two tracks on Spyglass Guest, but apart from that it was all keyboards. Dave Lawson remembers how, from the outset, their choice of instrumentation contributed to the group’s particular sound and approach.

“We didn’t give the guitars a thought at the time,” he says. “We just jammed with two keyboards and it seemed to work. With a guitar you’ve got a weapon in your hand – you wind it up and it’s very powerful. It’s extremely dynamic, whereas an electronic keyboard isn’t, really. You can wind clavinets up because they’ve got pick-ups in them, and you’ve got synthesisers which are powerful, but not in the same way as a guitar.

“It was a mixed bag because I was bringing some Samurai and Web things to the party and Dave had the music that he’d been writing when he was in Colosseum. Bar some numbers that Dave had written in their entirety, he would have chord sequences and I’d come up with a melody line and lyrics, and we’d knock it into shape from there.”

Greenslade feels that Bedside Manners Are Extra is perhaps his favourite of the band’s albums, but agrees that their self-titled debut – “Virgin Greenslade,” as he puts it – has a particular freshness about it. “There’s a very interesting selection of material on the first album; I’ve never really heard any other band play like that at all,” he says.

But although some of the music is rhythmically and melodically complex, from the outset the group’s considerable technical ability always served the material; as demonstrated on the twists and turns of the instrumental An English Western.

And while McCulloch isn’t mentioned as often as his more famous peers, his speed, deftness and impeccable timing made him one of the most gifted rock drummers of his generation. “It’s a question of having an affinity with the guys you’re working with,” Greenslade says. “And musically, we just slotted in like a jigsaw puzzle with the right pieces.

“Although we didn’t look like one, we were actually a live band,” he continues. “We enjoyed playing live more than being in the studio. We would rehearse the material, do a perfectly good recording and then we went on the road, and in six months... wow! We’d developed those pieces again.”

It must have been a nightmare for the road crew – six keyboards in a band – and they weren’t small and portable in those days. Bloody great Hammonds and Mellotrons

But was it a problem that the group didn’t have an onstage frontman? “That’s the thing: we did have someone out at the front,” Greenslade replies. “The most unlikely person – the bass player, Tony Reeves. And he was more than a bass player: if you listen to his lines they were almost like front line guitar work. We let him have his head in that direction, because he was very good at it.

“Each of us were playing at least three keyboards. It must have been a nightmare for the road crew – six keyboards in a band – and they weren’t small and portable in those days. Bloody great Hammonds and Mellotrons. I played the Hammond quite a bit, and a Fender Rhodes. Then I bought an RMI, an American electric piano and an ARP synth. Dave had a lovely ARP, and we wrote for all these voices.”

“It was a kind of thinking man’s band,” says Lawson. “We used to get quite a large following of gearheads, because synthesis was in its infancy; and I was slightly unusual because I chose an ARP. After the gig all these guys would be queuing up for autographs in loon pants and tie-dye t-shirts, with not a mini-skirted fan among them, except perhaps a Scotsman.”

But when the band strayed away from this core audience, enthusiasm was not guaranteed. Lawson recalls one time when they appeared live on a TV programme. “The audience, mainly teenage girls, had to be bribed with T-shirts and all sorts of things to even clap, because Slade were on the bill as well. So it was quite confusing.”

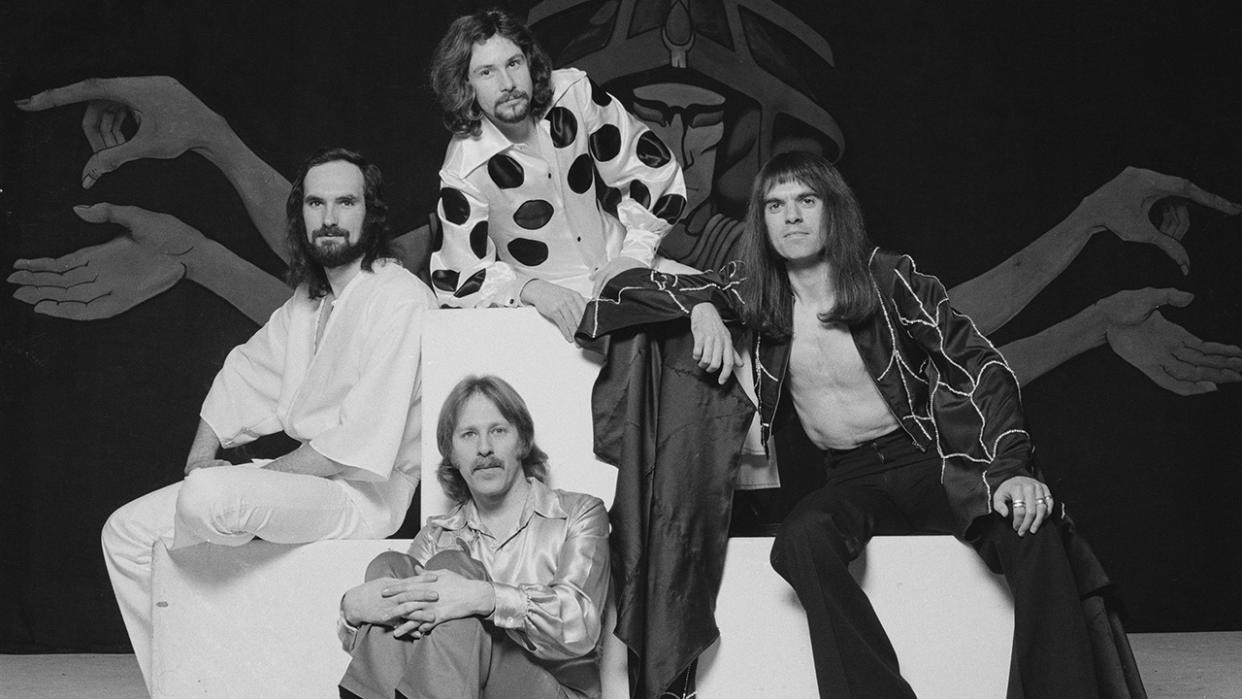

Lawson reckons that Greenslade were, image-wise, “a bit of a low-profile band.” But by 1975, Bambi (the wife of music critic Robin Denselow) made clothes for them. Lawson wore a fetching number with diamanté trim, McCulloch had lived a while in Japan and dressed with a Japanese theme, while incumbent bass player Martin Briley was kitted out in a skeleton suit. “Dave had a polka dot thing – he could have doubled in Billy Smart’s circus. It was the closest we got to Genesis,” Lawson quips.

Their keyboards attracted some unwanted attention from a particular type of gearhead, when in a typically odd 70s billing, Greenslade toured in the States with Kraftwerk. “In those days the sounds were made rather than just pressing a button,” Lawson explains. “On an ARP Odyssey, if you can imagine a surface with loads of little faders on it, all those faders are ‘in tune,’ if you like, so you’re in tune when you play the thing.

Kraftwerk barricaded themselves in the dressing room. Our reviews were great and Kraftwerk’s weren’t very special, put it that way, so we were asked to leave the tour

“When I got onstage, one of Kraftwerk’s crew – or Kraftwerk – had pulled every single fader down to zero, so the solo must have been the weirdest thing because I was trying to tune it at the same time as play. I mentioned it to our roadie, an ex-marine we called Lurch – huge, about six foot seven. Lurch wanted to have a word with Wolfgang Flür, and Kraftwerk barricaded themselves in the dressing room. Our reviews were great and Kraftwerk’s weren’t very special, put it that way, so we were asked to leave the tour.”

On Spyglass Guest it might have seemed that the two Daves were going their separate ways as they recorded some of their compositions in isolation, although they would both play on them live. But it was partly out of necessity as album deadlines were always looming, so any leisure time away from playing live would likely involve writing new material.

“I’d have my Fender Rhodes suitcase at home and a 7inches-per-second Revox tape recorder,” Lawson explains. “When I got to Doldrums, I recorded it and thought, ‘Well, there’s not a lot wrong with this recording.’ I wasn’t going to do it again in the studio. It wasn’t a cop out – I’d got it where I wanted it.”

After they released Time And Tide in 1975, the life of the band was cut rather cruelly short. They were with a management company who also looked after artists like Rod Stewart, and things weren’t working out.

“We were always treated by the management as something else because they didn’t understand our music anyway,” Lawson recalls. “It sounds arrogant but they didn’t have a clue or the faith to carry it forward.

“When I took the decision to leave the band, the van was on its last legs, we didn’t have a car to take the band around in, the infrastructure was crumbling and I couldn’t see that we had a future.”

We were always treated by the management as something else because they didn’t understand our music

Greenslade is loath to go into too much detail, but he notes that the two parties were bound together by a contract and so the only other option would have been to buy themselves out, which would have been beyond their means.

He was approached by the producers of the BBC TV series Gangsters, which ran for three years in the 70s, and he has continued writing soundtrack music, alongside an intermittent solo recording career which began in 1979 with The Pentateuch Of The Cosmogony – a kind of multimedia concept album with illustrations by fantasy artist Patrick Woodroffe.

While still in Greenslade, Lawson had been approached to do session work, initially for Stackridge’s album Mr Mick. He become “the synth guy you go to” in film music. He’s heard playing synth horn in the famous Star Wars cantina scene, and has worked on a number of other high-profile films like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and The Dark Crystal, and the BBC TV series The Blue Planet.

Greenslade and Lawson are both musically active and clearly have a great respect for each other. A version of Greenslade reformed in 2000 and made an album, Large Afternoon, but in the opinion of the man who gave the group its name, it didn’t have the magic of the original line-up. So is there any chance of more from the group, in some shape or form, live or on record?

“I wish the four of us now could go and do it all again, quite frankly,” says Greenslade. There are health issues that mitigate against them playing live, but Lawson reveals that he has some material left over from the 70s and that Greenslade played him some demos of material from the Pentateuch era that could be worked on.

“It would be nice to do something, but the practicalities of it all... it’s a possibility,” says Lawson after a pause. “It hasn’t been shelved for definite. The material’s certainly there.”