‘It’s in my DNA’: How the godfather of indie music became a rock ‘n’ roll snowbird in Miami

On a lazy South Florida spring afternoon, Thurston Moore, the way-out guitarist and inveterate noisemaker who co-founded the radically innovative indie-rock band Sonic Youth, is lounging in the shade of a poolside cabana at the Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, a favorite spot in the town of his birth.

As a TV plays scenes of the solar eclipse from around the continent, the gangly Moore, who is 6’6’’, slouches on a sofa in jeans and a short-sleeve shirt while his wife, Eva Prinz, and 12-year-old stepson Jules swim in the vast Biltmore pool, which today they have all to themselves.

Flocks of sparrows and parrots chirp and squawk in the palms overhead. Lizards peek out of the underbrush. The South Florida sun beams apparently unimpeded through a slight halo of.... clouds? Humidity? The eclipse? Hard to tell.

“Look at that,” Moore deadpans gleefully, glancing at the TV screen at eclipse-hunters standing in deep New England white stuff. “We would be up in the snow in Vermont right now. Instead, we’re down in Dade County.”

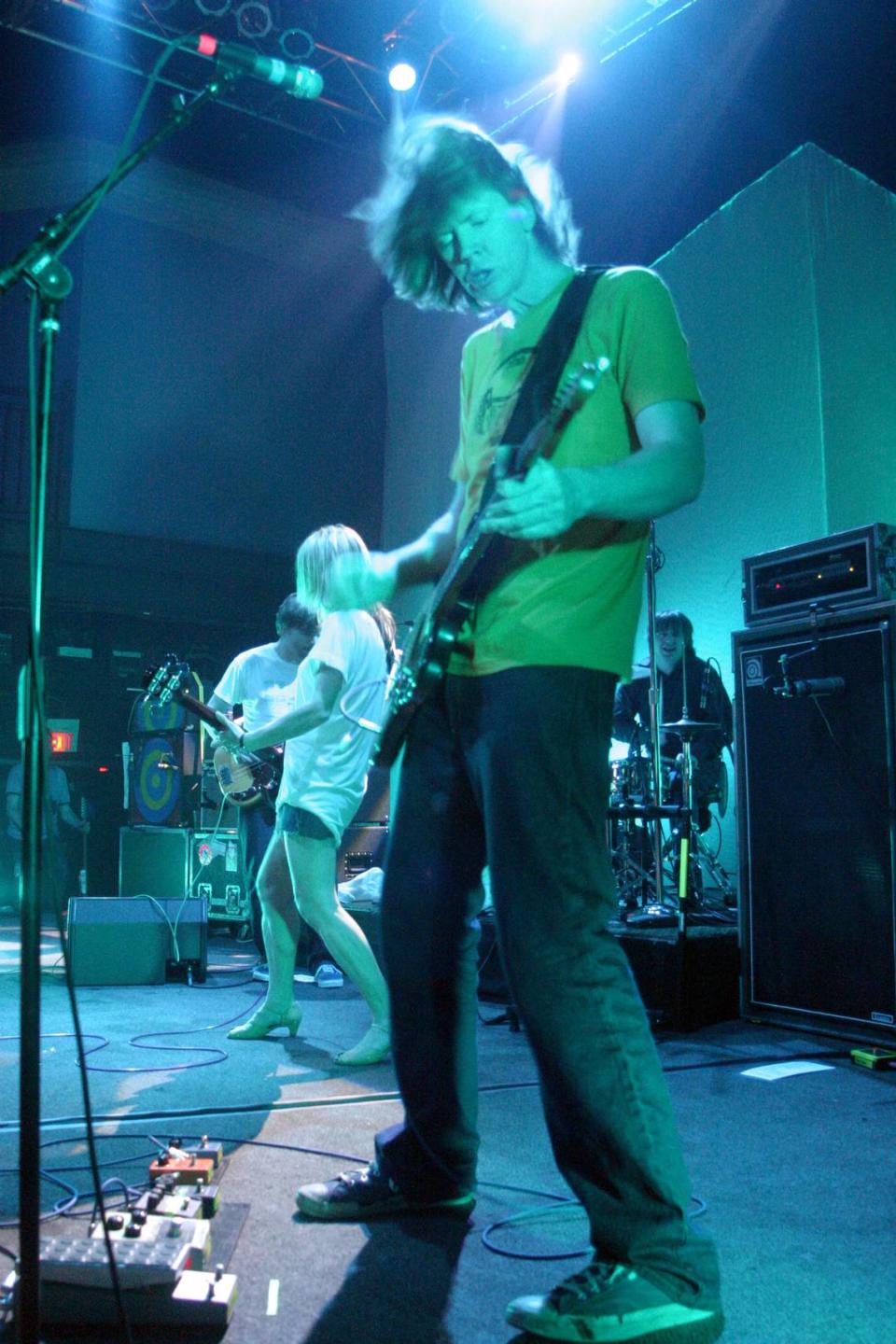

The posh Biltmore may seem an unlikely milieu for Moore, who emerged from grimy downtown Manhattan’s arty post-punk noise-music scene in the late 1970s and early 1980s with the raucous, boundary-busting Sonic Youth, which he started with artist Kim Gordon, who played bass, in 1981. Moore and Gordon, who alternated on vocals, were married for 27 years, until their 2011 breakup broke up the band.

Resolutely experimental and countercultural, and characterized by clamorous guitars in unconventional tunings, squalls of dissonance tempered by an edgy melodic appeal and lyrics that ranged from snide to declamatory, and sordid to poetic, Sonic Youth sounded like nothing else, then and now. One critic approvingly likened their sound at its most cacophonous to a New York subway train screeching to a stop at a station.

In a prolific 30 years of performance across the globe and 16 studio albums, their unflagging devotion to that discordant aesthetic turned Moore and Gordon into the revered godparents of alternative and indie rock. They helped lay the foundations for grunge and its leading exemplar Nirvana, which Sonic Youth took on tour when the Seattle band was all but unknown. To return the favor, Nirvana wore Sonic Youth t-shirts onstage at the peak of their fiery, brief life.

Sonic Youth’s 1988 album “Daydream Nation” is today preserved in the Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry.

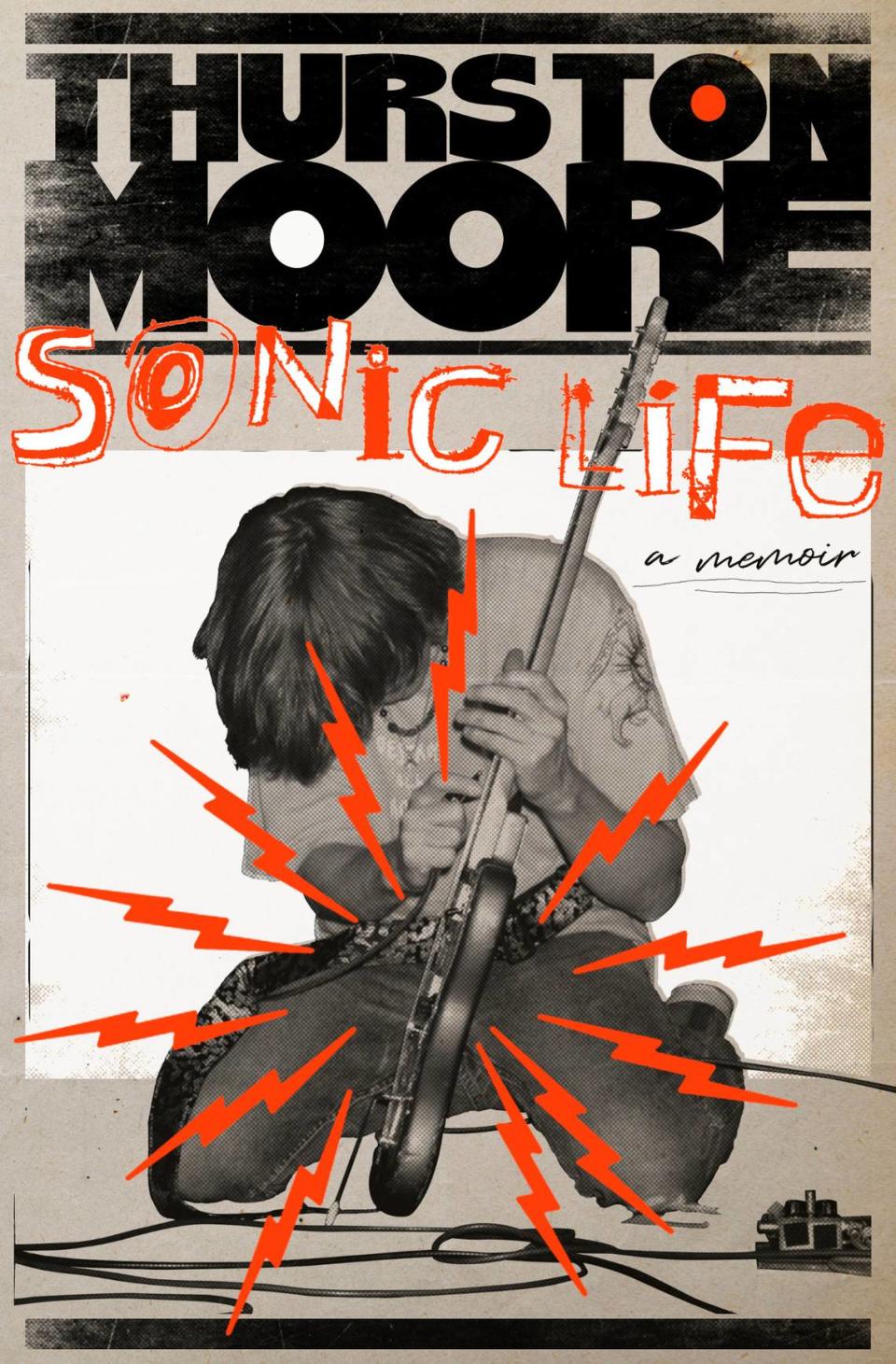

Genteel they may be, and worlds from punk’s spawning grounds in the Bowery and CBGB, but the Biltmore and Coral Gables are close to Moore’s heart. These are equally his roots, as Moore makes clear in “Sonic Life,” his recently published memoir.

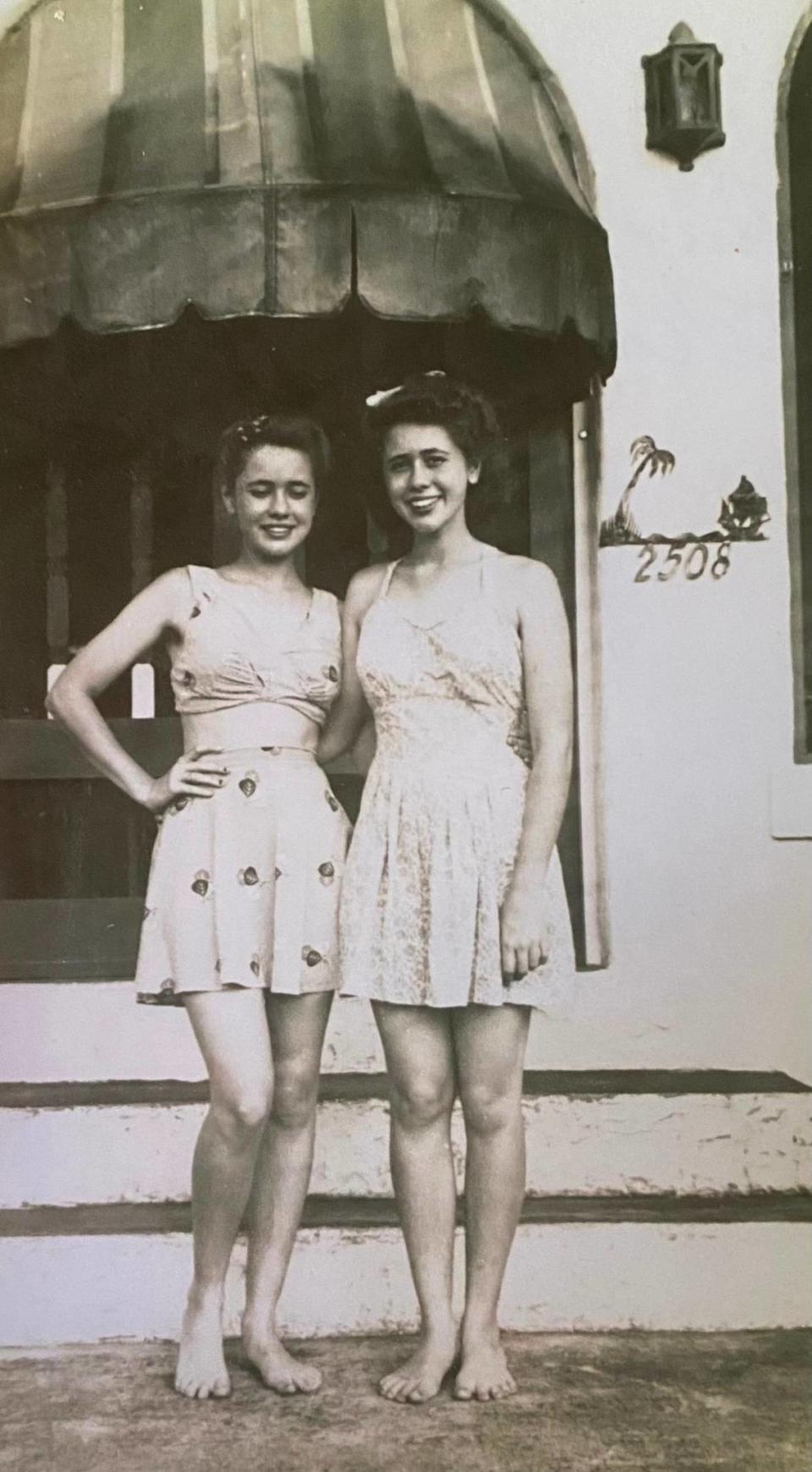

His mother, Eleanor Nann, and her twin sister Louise worked at the Biltmore as Red Cross volunteers during and after World War II, when it was a military hospital. The Nann sisters, reared in the Gables, lived a short walk away and attended Catholic school at St. Theresa and Mass at the Church of the Little Flower, where Moore’s parents were married.

Eleanor met Moore’s father, George Moore, a classical musician and professor of art and philosophy, when they were both enrolled at the University of Miami’s music school. Born at Doctor’s Hospital, Thurston attended Epiphany Catholic School, where the sisters once washed out his mouth with “holy soap,” before moving in 1967 at age 9 with his parents and two siblings from the Ponce-Davis neighborhood, wedged between the Gables and South Miami, to western Connecticut, where his father got a university teaching job.

Now, at 65 and more than a decade removed from Sonic Youth, Moore -- whose subsequent solo career has been no less sonically deviant and who has a new album coming out -- quietly returns home every winter with Prinz. For several years, they have been digging in low-key fashion into what he describes in the memoir as the “charmed and enchanted enclave” of Coral Gables and surrounding Miami. Moore says he’s looking to settle down.

The Moores haunt Books & Books, flip through bins at the city’s half-dozen eclectic and well-stocked record shops -- Moore is a zealous collector of vinyl, poetry books, fanzines and ephemera, and Prinz is an art-book editor. They attend as many Miami Heat home games as they can. They chow down at a roster of favorite ethnic and neighborhood spots, hang with friends and family, and, gradually, have become involved in the local music and cultural scenes, issuing records by Miami bands Seafoam Walls and Las Nubes on their independent label, Daydream Library Series.

The couple, who live in London in summer and fall, took over a rental home in the North Gables from the late Eleanor, who returned to the city in her later years. They ride their bikes -- the Moores don’t have a car -- or hitch rides with friends. As Moore likes to say, the city is in his DNA.

Call him a rock ’n’ roll snowbird.

“When Eva and I came down here to visit my mom when she was renting a house here, and we would stay for a bit, Eva fell in love with it,” Moore said. “This is a really diverse city. And it has...”

”The best coffee on the planet,” chimes in Prinz, who has joined Moore in the cabana.

Moore continues: “The tropics, nature, it’s just she was, ‘I love it down here.’ I was, ‘You don’t have to tell me.’ ”

Thurston and Eva Moore’s top 10 Miami restaurants

‘Sonic Life’

The Gables house is where Moore wrote his widely reviewed and well-praised memoir, “Sonic Life,” during the COVID pandemic. Not a typical look-at-me memoir, the book is in part an exhaustive, often-droll reconstruction of a vanished Bohemian downtown Manhattan and the bands, artists and performers both famous and obscure who shaped the punk and post-punk movements.

Sonic Youth doesn’t make its appearance in the 468-page tome until nearly halfway, and in the memoir’s narrative the band’s development and ascent parallel punk’s splintering across the country into subcultures like no-wave, hardcore and grunge and alternative rock.

The book opens with a key moment for young Thurston. He is a mere 5 years old when his brother Gene, 10, brings home a copy of the Kingsmen’s louty, murky garage-rock classic single “Louie Louie,” which the boys proceed to play in “constant revolution” on their parents’ record player.

By the 1970s, now in Connecticut, it’s Jefferson Airplane on the turntable and Thurston is sneaking into his brother’s room and breaking into a locked case to fiddle with his treasured Fender electric guitar, until Gene presents him with one of his own. That “crazy-beautiful sunburst Fender Stratocaster” would later be stolen from Moore’s apartment in New York’s then-perilous, junkie-ridden Alphabet City.

Moore, almost entirely self-taught on the guitar, was never interested in learning to play conventionally. He experimented with alternative tunings and cheap guitars with sticks and other objects rammed into the fretboard to produce otherworldly sounds as he picked and slashed at the strings.

A few years ago, he was interviewing Iggy Pop, fellow Miami rock royalty, for a video for the U.K. music label and shop Rough Trade at the cottage on the Little River that the godfather of punk uses as a creative studio and hangout.

“We were sitting around jamming and talking about ‘Louie Louie,’ and I could only play the beginning of it, and he started laughing,” Moore said.

If the garage classic’s three chords eluded Moore, his memories of Coral Gables have remained vividly detailed. In a passage near his memoir’s opening, Moore lovingly evokes the look and feel of Coral Gables, “a paradise of huge banyan trees presiding over narrow streets.”

There was much more, Moore told Books & Books owner Mitchell Kaplan during a full-house discussion at the Gables bookstore in March, at two hours possibly the longest ever author appearance there. But the editors at Doubleday cut his 900-page manuscript by nearly half, including that anecdote where the nuns “brutalized” him by jamming a bar of soap in his mouth after he uttered an obscene word he didn’t know the meaning of, Moore said.

Those were otherwise idyllic days, Moore recalled at the Biltmore. There were frequent forays to the mangrove wilds of Matheson Hammock Park and visits to the Miami Beach home of his mother’s twin on La Gorce Drive. His mom would walk him to school at Epiphany, and he would ride his bike around the neighborhood. The house, on Southwest 52nd Court, is still there.

“We had an avocado tree and a mango tree, and my brother had a pet iguana in a cage in the garage. We grew up with all that stuff, batting away spider webs at Matheson while climbing over the mangrove roots,” Moore said. “Across Davis highway was all open, it was all woods and forest and what have you. We’d go in there and run around the banyan trees with the spiders and the snakes and the iguanas and lizards. Now it’s all McMansions built on top of that land.”

The Gables roost has been fruitful in other ways, too. Moore composed and arranged the music for his new album at the Gables house, where he has a small recording set-up. “Flow Critical Lucidity,” recorded in London with his U.K.-based band, is set for release Sept. 20 on Daydream Library, an arm of his and Prinz’s book-publishing concern, Ecstatic Peace Library.

A single from the album, “Rewilding,” out for Earth Day in April, reflects Miami influences. The percussive track features what sounds very much like bongos in the mix, described as “coconut drum beats.” The lyrics drop a reference to Miami’s Coral Morphologic, the art-meets-science producer of vividly colorful Biscayne Bay underwater reef life images that is making a video for the song.

Becoming locals again

A close Miami friend, photographer Susie J. Horgan, said Moore’s and Prinz’s immersion in local life has been genuine and unassuming. She and her husband Harry Horgan, co-founders of Coconut Grove’s Shake-A-Leg sailing program for people with disabilities, squire them around on far-ranging explorations for culture and eats.

“We have a lot of fun, we really do,” Horgan said. “They spend more and more time here. They go to the theater. They go to the bookstore. It’s not like he’s choosing to just lie in the sea here. Quite the opposite. It’s a place to come and rejuvenate and work privately. It’s a true feeling of being rooted.”

It helps that in Miami, where club, hip-hop and Latin music have long overshadowed a lively underground rock scene, Moore is not often recognized in spite of his conspicuous height and distinctive mop of reddish hair. When he is, Horgan said, Moore is gracious and down-to-earth.

One time, when the Horgans and Moores dropped in for ice cream at the Haagen-Dazs on Miracle Mile in the Gables, the young staff recognized the Sonic Youth frontman, even if they tried hard not to get too excited.

“The kids in that place just died. They were trying to be cool,” Horgan recalled. “One, the guy with the mop, was an interesting young musician and knew very detailed information about Thurston’s guitars and songs.”

Moore tried to divert their attention to Horgan, who by happenstance had worked at a Haagen-Dazs in Washington D.C. in the early 1980s with two fellow scoopers and future stars of hardcore and indie rock, Henry Rollins of Black Flag and Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi -- musicians and friends Moore has long championed.

Horgan’s photos of the D.C. hardcore scene, which Moore and his Sonic Youth bandmates admired when they first met, were later published in a book that Moore and Prinz helped put together for Rizzoli, “Punk Love.”

The way the Horgans and Moore became friends underscores the incestuously tight-knit nature of the U.S. underground rock scene that Moore documents in Sonic Life. Strangely enough, their friendship was cemented through Gables links. Susie Horgan grew up with Bob Lawton, Sonic Youth’s agent, who arranged for the band to play at a Shake-A-Leg benefit in the early 1990s in Newport, Rhode Island, where the organization was first based.

“No one was prepared for Thurston’s guitar,” Horgan said. “He blew out the power, and we became friends.”

A few years later, the friendship was rekindled when Horgan, who was the house photographer at Books & Books and whose mother grew up in Coral Gables, was working at the store. In walked Moore with Gordon and their daughter, Coco Gordon Moore, in a stroller.

“That’s when we discovered the Coral Gables connection,” Horgan said.

Books and records

The books and vinyl records Moore and Prinz produce under their small imprint are, characteristically, of exacting design and quality. The books are printed in the United States, which allows close supervision of production, while the records are impeccably pressed abroad, some on translucent colored vinyl, and bear labels of exquisitely minimalist design.

Ecstatic Peace has published books on the Velvet Underground, Norwegian black metal musician Necrobutcher, a particular Moore favorite, and a limited-edition work by Yoko Ono, among others. Moore and Ono -- he calls her “the best Beatle” -- have collaborated several times, including on a mostly improvised 2012 album with Gordon that’s best suited for ears well-attuned to screeching and skronking.

Among the releases by Daydream Library, the music label, are Moore’s own work of recent years and two records by Miami bands that reflect the local rock scene’s diverse roots and influences, including an LP by Seafoam Walls, a Caribbean-inflected rock group led by Haitian-American artist and guitarist Jayan Bertrand, and a 7-inch single by Las Nubes, a female duo who sing fuzzy noise-pop tunes in both Spanish and English.

Moore and Prinz also organized a band showcase in February for Seafoam Walls and Las Nubes, along with other Daydream Library musicians, at Little Havana’s hip Bar Nancy. That the place was packed despite Miami’s reputation as a tough city for live music was proof to Moore of the appeal of the collaborative, DIY approach he’s always stuck to.

”If there is a place where something like that is happening, people will go,” he said. “Create a band, create a venue. We just promoted it online, big time. ‘Miami, this is happening, come on out!’ And people came out. It was a great night.”

Seafoam Walls’ record, “XVI,” was created after Prinz met Bertrand at the since-defunct Center for Tropical Affairs outdoor garden venue in Little Haiti. Moore and Prinz liked the band’s music so much they paid to master, press and release the recording. Moore then took Bertrand, solo with his guitar, on a tour of Europe to open for his band.

It was a gratifying and audience-expanding experience for Bertrand, whose parents ran Haitian roots-music group Koleksyon Kazak in Miami in the 1990s. He grew up listening to both the music of his homeland as well as hip-hop and indie rock, including Sonic Youth. The association with Moore gave Seafoam Walls instant cred, gleaning positive notices in national outlets like Pitchfork, Spin and Afropunk that he grew up reading, Bertrand said.

“Even him posting that they were signing us to their label gave us an overnight boost,” Bertrand said. “It got us into the circle of the artists that we admire. It got their attention. I mean, that was my first time playing to sold-out crowds. Those shows were incredible. It’s crazy enough I got to play with some of my musical heroes, but playing in front of that many people was nerve-wracking, and cool.”

“And it was a great chance to see Thurston’s personality and interact with him more. He’s always cracking jokes, always keeping the mood light. I really love that energy about him. It’s very easy to be around him.”

For Las Nubes’ Ale Campos and Emile Milgrim, the single was a way to drum up interest in their upcoming new album, “Tormentas Malsanas,” and something fans can buy at their shows, as opposed to a download, to boost their income.

“It has helped us get more write-ups and get people’s attention,” said Campos, who first met Moore while performing at the legendary, now closed Churchill’s Pub in Little Haiti, the hub of the local scene; they got reacquainted later while she was working next door at Sweat Records. “People want to have something physical. They collect vinyl, they collect tapes. Nowadays, if you’re putting out music on a streaming platform, you’re not making money.”

It’s also good for a music scene that doesn’t get the attention it deserves, she said.

“I think it’s pretty cool that someone like Thurston wants to come here and try to uplift the bands in our community instead of going to L.A. or New York,” Campos said. “There is a really good music scene here. A lot of people don’t know about it.

“I hope with Thurston doing this, it puts a spotlight on us and the Miami music scene.”

Moore said promoting Miami bands is an extension of what he and his Sonic Youth bandmates always did -- bringing exposure to the music and musicians that helped shape them or had earned their esteem, in particular those at the margins of popular culture, whether West Coast hardcore, extreme experimental noise music from Japan and Berlin, or the neo-folk fingerpicking acoustic guitar of John Fahey.

To some significant degree, Moore said, he was primed by his upbringing in a supportive household filled with music, art and books. His father was always playing piano or classical music on the record player and his mother, who took on a role as homemaker, was an enthusiastic supporter of her children’s interests. His brother collected records, which the young Moore regarded as a magical portal to other worlds he yearned to explore.

“My father, he was a philosopher,” he said. ”When we lived in South Miami, I remember him having other professors come over and they would have lawn chairs in the back, and they would be, God knows what they were discussing. But I knew there was a bit of a brain trust going on there. There was an intellectual exchange going on, and that really had an effect on me, and I think when I got involved in music, a lot had to do with wanting to be in that kind of micro-community where that exchange was happening.”

Moore is almost entirely an auto-didact. There wasn’t much going on culturally in semi-rural Connecticut, and he did poorly at school. One summer back in Miami, where the family would regularly return on vacation, a hippie in Coconut Grove sold him an underground newspaper for 50 cents, the first hint he had that something called the counterculture existed.

“I was always interested in music that was kind of more marginalized. It was more challenging. I never really felt like I wanted to make music just to be popular. At all,” Moore said, laughing.

The broad, exploratory musical taste only hints at the extensive range of Moore’s interests and activities, to which he has given increasingly free rein in recent years. He has published poetry, edited a poetry journal and recited his verses at the O, Miami festival onstage with Richard Blanco. He teaches an annual summer course on the poetry of the Beats and underground writers at the Jack Kerouac School of Disemboed Poetics, founded by Allen Ginsberg, at Naropa University, a Buddhist school in Colorado.

He has performed piercing live improvisations with local noise eminence Frank “Rat Bastard” Falestra, founder of the International Noise Conference that takes place more or less annually in Miami. In March, Moore joined Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones onstage at Tennessee’s Big Ears Music Festival for 25 minutes of free-form sound improvisation at earbleed volume that had some audience members, perhaps mistakenly expecting something with a backbeat, fleeing for the exits.

“It was really polarizing. I mean some people were just shattered by it, in good ways and bad ways. We took no prisoners, let’s put it that way. That kind of collaboration is really intense. Some people thought it was brilliant, and some people thought it was Satanic. They went running out of there like this,” Moore said, holding his hands over his ears. “But we knew going in it was going to be that kind of situation.”

‘I definitely want to settle down’

Moore says he’s done doing long tours, going through airports and getting in and out of vans. He has a heart issue that’s under control, but doctors have advised him to slow down, and he says he’s more than ready. For his new album, he and his band are doing an abbreviated series of shows in Europe.

He hopes to buy a house in Coral Gables or Miami, with a garden, and spend more time at home. His dream is to run a second-hand bookstore -- there are few here, he notes -- and to write fiction. He’s working on a novel.

But even rock stars have been dinged by real estate sticker shock in South Florida. He and Prinz have found nothing they like and can afford, Moore said. In London, they also rent.

“I definitely want to settle down. I just want to write,” Moore said. “I’ve always had a dream of being a writer who works in a bookstore with two dogs and a cat and doesn’t leave that bookstore except to go home and write his novels. That’s the lifestyle I would really want.

“I always have my eyes out for a place to buy here. So I could put my hands in the soil. But to find a place for less than a mil or two is kinda tough. Maybe the housing market will crash and I can find a house. It just blew up in the last five years. It’s impenetrable. There are all these empty houses because these people live in Europe and they come here once in a while. It’s all this parked money. It drives me crazy.”

Moore said he doesn’t need anything extravagant.

“My father was a schoolteacher. My mother was a homemaker. Baloney sandwiches for dinner,” he said, leaning back in the Biltmore cabana couch and smiling. “That to me was my favorite dinner.”