Who does Bob Dylan revere? The answers are in his puzzle of a new book, 'The Philosophy of Modern Song'

In 2004, Bob Dylan released an autobiography of sorts. “Chronicles: Volume One” methodically charted the troubadour’s trek but then took enough factual detours to make the entire literary itinerary suspect.

Now we have a new Dylan book, “The Philosophy of Modern Song” (Simon & Schuster, 352 pp., out now). An argument can be made this is actually his autobiography.

Through this enigmatic, flattering and insightful collection of essays dissecting what Dylan considers the recorded era’s greatest songs, we inch closer to understanding a towering, vexing, soulful and revered artist – born Robert Zimmerman in Hibbing, Minnesota – who has always worked hard to throw us off that trail.

We sprinkle a few gems from “Modern Song” below, revealing just who garners the king’s nod (the list ranges from The Who to Marty Robbins, from Johnny Cash to The Clash). Little of it is linear. Some of it is confounding. All of it is riveting. But let’s start with why it’s important.

The clues to Dylan lie in the songs

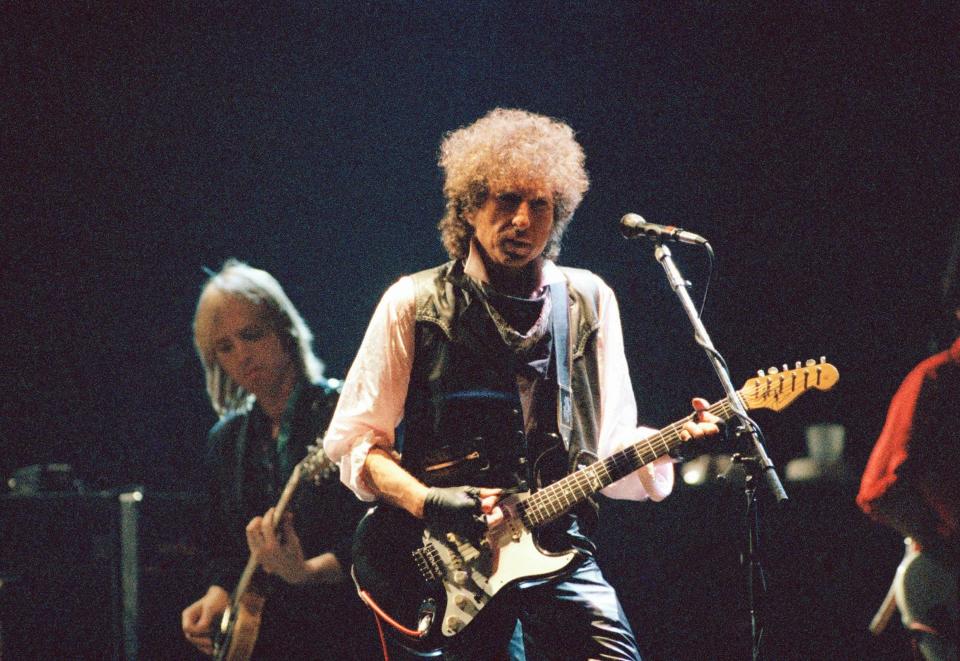

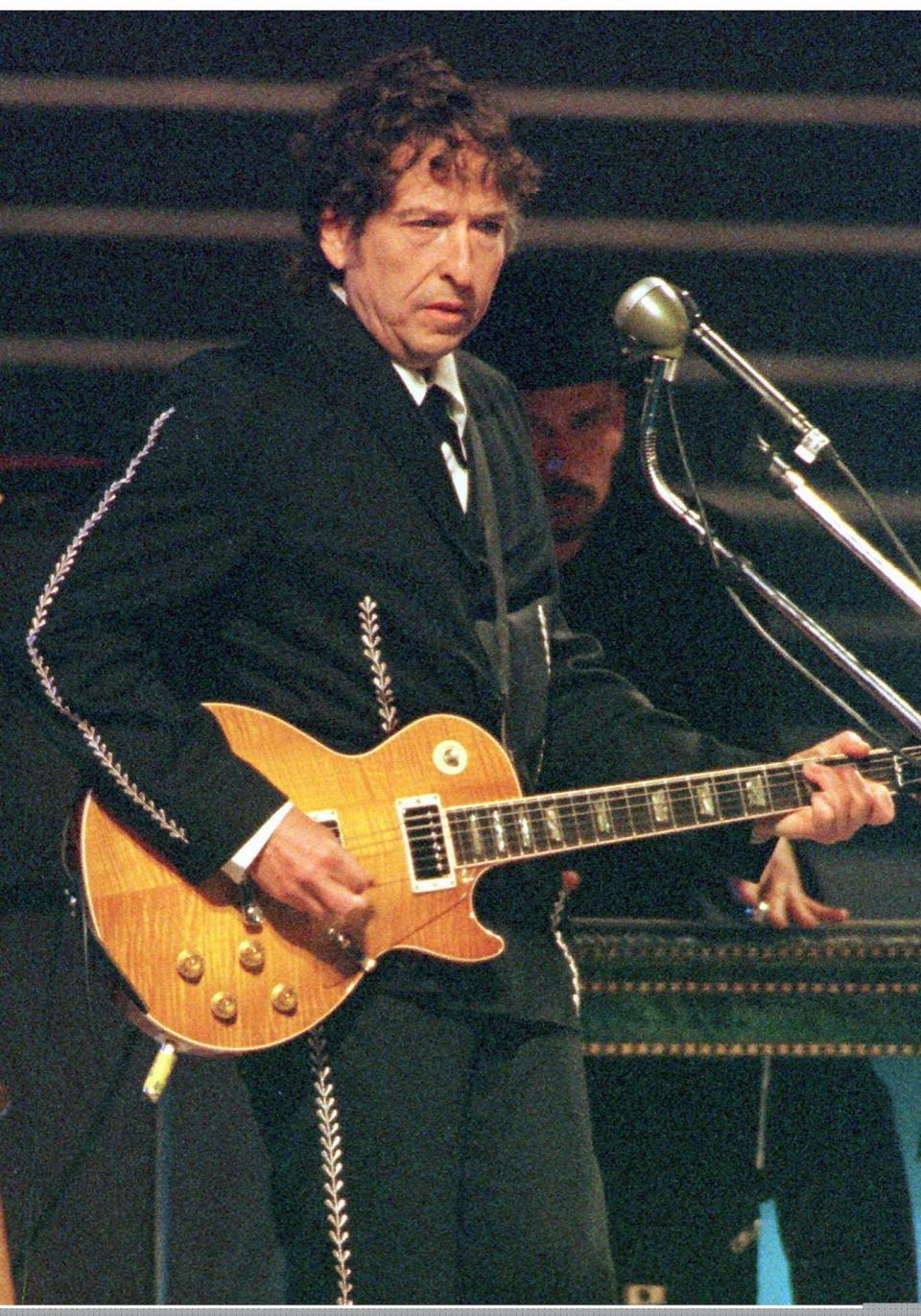

Dylan is 81. He’s been famous for about 60 of those chameleon-like years. A protest song singer who protested that mantle. A religious convert who converted back. A ’60s icon who reinvented himself in the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s and so on. He’s as easily pinned down as the wind.

So if there is any true clue as to the source of his magic, it is not found in any biography but rather in the songs he revered. He said so himself.

“These songs didn’t come out of thin air, I didn’t just make them up out of whole cloth,” he told a rapt MusicCares audience in 2015. “It all came out of traditional music: traditional folk music, traditional rock ’n’ roll and traditional big-band swing orchestra music.”

He explained: “I sang a lot of ‘come all you’ songs. There’s plenty of them. There’s way too many to be counted. If you sung all these ‘come all ye’ songs all the time, you’d be writing, ‘Come gather ’round people wherever you roam, admit that the waters around you have grown/Accept that soon you’ll be drenched to the bone’ – the opening to his anthemic 1964 classic, “The Times They Are A-Changing.” It's always about the songs.

Dylan loves Elvis – Costello that is

“Pump It Up,” released in 1978, helped put Elvis Costello and the Attractions on the map. It bobbed and weaved. Dylan was paying attention to both the craftsman and his creation and offers his own take on the song's intended audience.

“It’s not like you have a promising future,” Dylan writes. “You’re the alienated hero who’s been taken for a ride by a quick-witted little hellcat, the hot-blooded sex-starved wench that you depended on so much, who failed you.”

Of Costello – one of just a handful of artists he opines about directly in essays covering more than 60 disparate tunes – he writes that he and his band were “better than any of their contemporaries. Light-years better.”

He also finds time to compliment Costello’s suit and tie look: “The Brits, if nothing else, had dignity and pride and they didn’t dress like bums. Money or no money.”

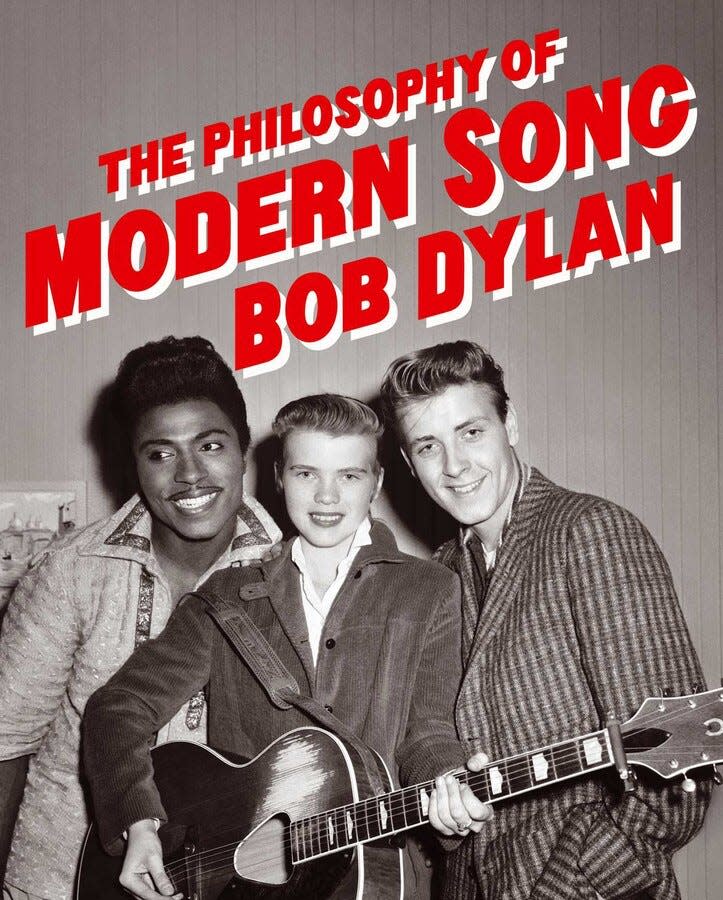

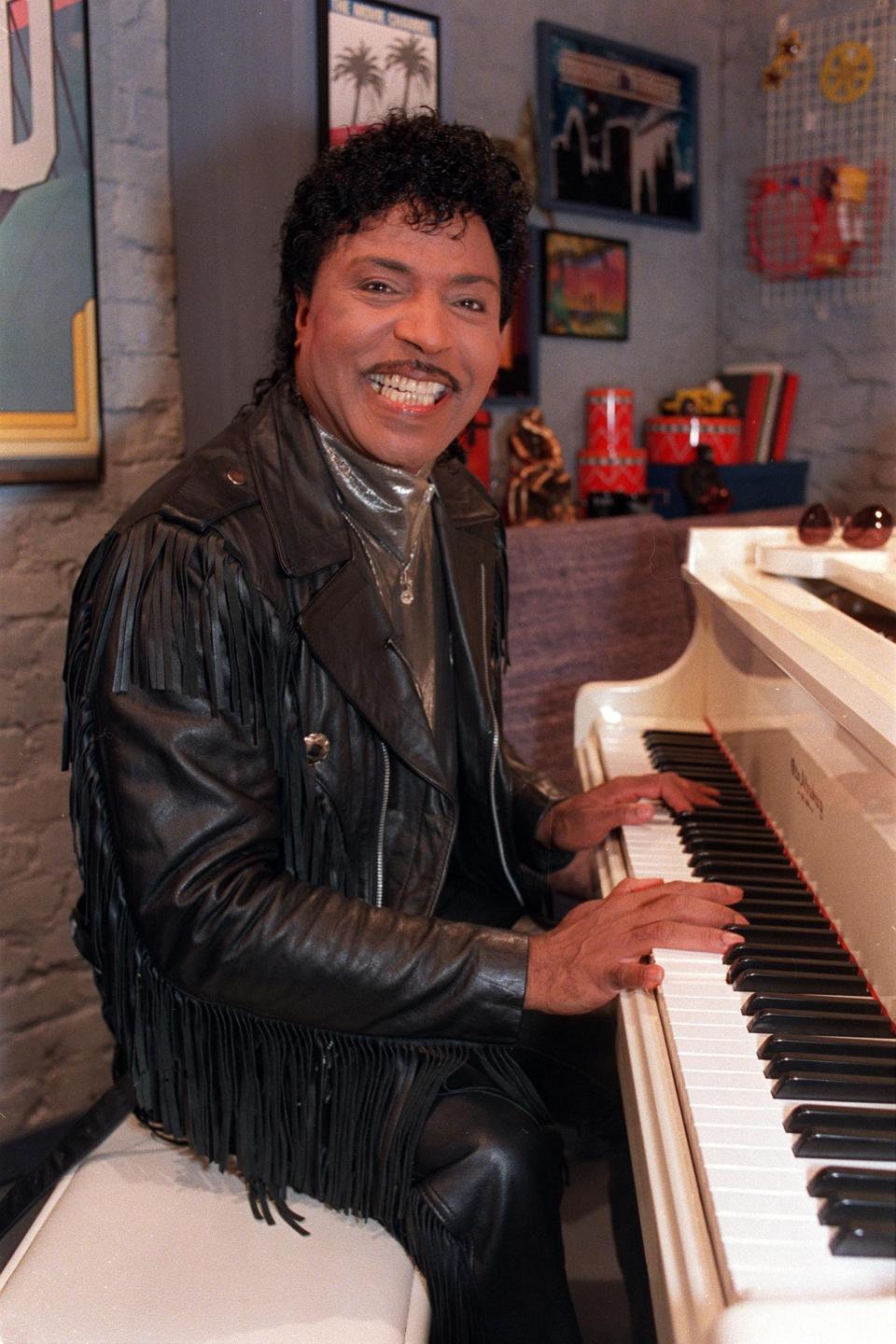

All hail rock ’n’ roll’s supreme preacher, Little Richard

“A-wop-bop-a-loo-bop-a-wop-bam-boom. Little Richard was speaking in tongues across the airwaves long before anybody knew what was happening,” writes Dylan in his reverential take on that seminal 1955 single, “Tutti Frutti.”

Dylan particularly admires the sly way the singer made a nod to homosexuality at a time when doing so was unthinkable. He was “the master of the double entendre. … Did you ever see Elvis singing ‘Tutti Frutti’ on ‘Ed Sullivan? Does he know what he’s singing about? Does Ed Sullivan know?”

USA TODAY's new book club: Why we want to read Stephen King's 'Fairy Tale' with you

For Dylan, the singer was at rock’s ground zero. Little surprise Richard’s smiling face, just one of many compelling images lacing the pages, adorns the cover of Dylan’s book.

“Little Richard was anything but little,” he writes. “He’s saying that something is happening. The world’s gonna fall apart. He’s a preacher. ‘Tutti Fruitti’ is sounding the alarm.”

Dylan the diehard Deadhead

Dylan famously toured with the Grateful Dead in 1987. On the surface, strange bedfellows. Looking closer, not so much. Winding lyrics, solid rhythmic backbeat, a disinterest in being hemmed in.

“Truckin’” is off the Dead’s 1970 album “American Beauty, and that now iconic song hits all the right notes for Dylan, who hails its stream of consciousness drug-fueled rap by repeating back many of its lyrics.

“This song is medium tempo, but it seems to just keep picking up speed,” he writes. “It’s got a fantastic first verse, which doesn’t let up or fizzle out, and every verse that follows could actually be a first verse.”

That’s the wind up, now the delivery: “Arrows of neon, flashing marquees, Dallas and a soft machine, Sweet Jane, vitamin C, Bourbon Street, bowling pins, hotel windows, and the classic line ‘What a long strange trip it’s been.’”

Musing on war by way of Edwin Starr

Many times in “Modern Songs,” Dylan uses a song title just to riff on something that piques him.

For example, the coda to his essay on Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes’ “If You Don’t Know Me By Now” (1972) is about religion (Dylan briefly was a born-again Christian in the late ’70s). And the chapter on Johnnie Taylor’s 1973 release, “Cheaper to Keep Her,” is a rant about the billion-dollar divorce industry.

So it’s little surprise that Dylan leverages his essay on “War,” the indelible Vietnam-era classic by Edwin Starr, to wax philosophical on war, something he did lyrically on early hits such as “Masters of War.” As is his wont, he sees the paradoxes.

“Wars have raised people, freed them from oppression and actual slavery,” he writes. “Wars have reopened trade routes and channels of communication. And as history is written by the winners, so it is with war. … You have to look to the losers to find the atrocities.”

Las Vegas and the lesson of house rules

“Viva Las Vegas” was released in 1964 and written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shulman. Dylan’s entire book is dedicated to Pomus – a larger-than-life original who also penned “Save the Last Dance for Me” – so you know he’s going to bring the heat.

“This is a song about faith. The kind of faith where you step under a shower spigot in the middle of the desert and fully believe water will come out,” he writes, loping into a section about Elvis and his triumphs and fall in that unbending Nevada town.

It’s an alternate take on the glossy original. A meditation on the city's seductive if tragic lure, a place that demands "an atomic-powered inner spirit" even though all the players know what happens next.

“Today, Elvis is gone, the Colonel (Tom Parker) is gone, Doc Pomus is gone. B.B. (King) and Dr. John are gone. Meanwhile, Hilton now owns thirty-one hotels in Las Vegas.” You can almost hear the sneer. “The house always wins. Viva Las Vegas.”

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Bob Dylan's new book reveals which music legends he admires the most