Emmy flashback: Talking to the two people who helped Chris Rock 'Bring the Pain'

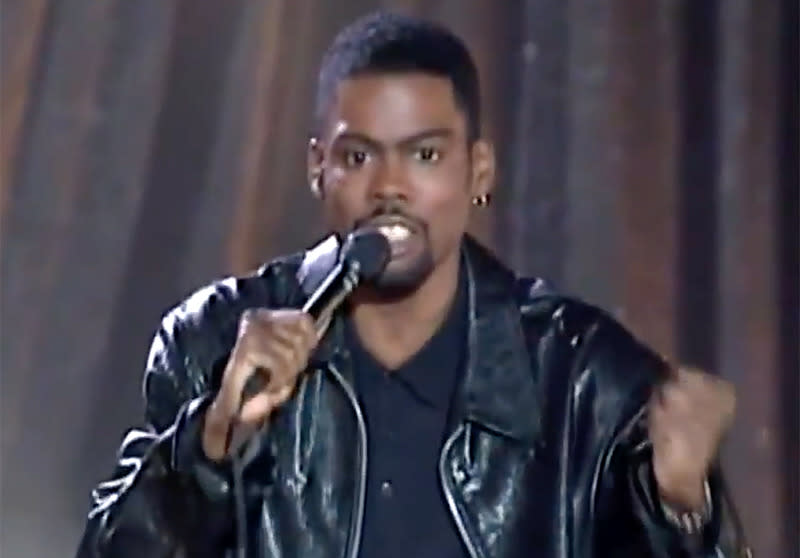

These days, Chris Rock is firmly ensconced in the upper echelons of stand-up comics. Twenty years ago, though, he was a self-described has-been who struggled through four seasons on Saturday Night Live before joining In Living Color only to see Fox almost immediately cancel it. Rock desperately needed a career reinvention and brought it with Bring the Pain, his 1996 HBO comedy special that tackled hot-button topics like race and politics with a newfound ferocity that was still hugely funny.

Premiering on June 1, to rave reviews and big audiences — and after the cut-off deadline for that year’s Emmy awards — Bring the Pain proved powerful enough to linger in the public imagination until the 1997 awards cycle, nominated for and winning a pair of Emmys that September and making Rock one of the most popular comics in the country. On the 20th anniversary of its Emmy victory, we spoke with Keith Truesdell and Sandy Chanley — the director and producer, respectively, of Bring the Pain as well as a number of other defining comedy specials for the likes of Adam Sandler, Kathy Griffin, and Bill Maher — about Rock’s panther-like performance and how Bring the Pain is like a ballet.

How did you get your start producing stand-up comedy specials?

Sandy Chanley: We started our company, Production Partners, in 1990. Prior to that, we had been working in the comedy industry for another producer, so we were aware of television comedy specials for a good three to four years. After starting Production Partners, we did a couple of specials for HBO. We started getting nominated for and winning CableACE Awards. At the time, that’s what cable programming could be up for. So we’d be in the stand-up comedy category at the CableACE’s and people would say, “Man, if you lose, you’re really a loser!”

Keith Truesdell: I had been directing before we started Production Partners, doing all different kinds of things. Directing was always my position, whether it be live or videotape or television. It’s always been what I wanted to do and was very fortunate to get to do it. Sandy and I definitely formed a partnership where we have our specific roles, and watch each other’s backs in a really great way.

Chanley: He’s not nearly as good a producer as I am. And I suck as a director! [Laughs]

In those early days, did you have a kind of comic you specifically wanted to work with? Did you ever reject anyone?

Chanley: I don’t think we ever turned anyone down. We got really lucky and weren’t ever offered anyone that wasn’t brilliant. Even Andrew Dice Clay; there was a moment in time we almost got to produce a special that he was doing. I think they postponed it, and then we couldn’t do it because of scheduling or something. Even with all the crazy sexism the guy was promoting at the time [we wanted to do it]. If you went to an Andrew Dice Clay concert and you were a women, he would start into some of that stuff and men would be looking at you like, “I could do that to you.” I said, “We’ll put him on the stage, and capture that. It might be a little dangerous.”

When did the relationship with Chris Rock start?

Chanley: We knew him through his manager at the time, and produced his first HBO special, Big Ass Jokes, in 1994. The material for that wasn’t as edgy, but it was really smart and really funny. There was something really special about how he could deliver a joke and still be adorable. You just want to pinch him on the cheeks.

The Chris Rock we see in Big Ass Jokes is very different from the performer in Bring the Pain. When did you first get the sense that the new material would be such a departure?

Chanley: He was in Los Angeles while working on the Bring the Pain material, and he would go to The Comedy Store at midnight. I’d pop in to see him, and he’d just have this little notepad on the stool next to him. He wasn’t even really performing the material so much as he was just tossing it out there to the 10 people sitting in the audience. But the material he was doing! I was sitting there in the back going, “Holy crap!” Sitting there listening to what he was about to lay down on an uncensored network, [I knew] it was going to be a breakthrough. Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor were already grabbing onto these outrageous, but realistic concepts. Chris just took it and went into areas where people still won’t go. No one has the guts to do it now. I’d love to stand on a stage doing [the material] somewhere and just see what they would throw at me.

Even the way he moves onstage in Bring the Pain is different than in Big Ass Jokes. He’s constantly pacing back and forth, and attacks each joke.

Truesdell: When he was working out the material, he never did that. It was only in the last couple of venues that he was actually getting into that pacing panther mode. You have to know that he’s not going to do it the same way twice, and it was really important for me to learn his act as opposed to just watching it once. We traveled to different cities when he was working on the material and I made notes, memorized things and came up with concepts that you didn’t see very often at the time. For example, the audience cutaways [in most comedy specials] just cut to the audience and then they go back to the person onstage. I came up with things like, during an applause break, we’ll start the camera on the audience and then pan to the stage to tie it in. I really wanted the audience at home to feel like they were experiencing the moments as if they were there. I know everybody says that, but it’s a difficult thing to do.

Chanley: As Chris evolved, Keith would evolve how he was going to cover the material. Most stand-up comics stand in one spot next to a stool, and if they even raise their arms up, it’s like, “Oh, we’ve got to get a little wider [with our frame].” Keith was really excited about how to handle Chris’s movements. He had to uniquely figure out how all those cameras were going to be able to move the entire time, including a close-up camera, and stay in focus. Keith made it look more like a film. The way he captured it, you really felt the wildness and energy of the crowd. A lot of the techniques he created, we used from that point forward.

Truesdell: It just feels like a ballet to me, you know? If Chris got to the point where he started to calm down, I knew these places where I wanted to ease in to the close-up shot to make it feel like you’re right inside what’s going on [in his mind]. We did it all live, too. You don’t notice it, and you shouldn’t notice it, but it’s not random things that are happening; it was all planned out. We brought the whole crew from Los Angeles, by the way. We knew we had to have the best of the best.

Chanley: Chris’s words were so brilliant, and you could so easily capture them the wrong way. He doesn’t have control over everything that surrounds him, so you have to protect his brilliance. We worked with him to figure out ways to stay in the zone before the show. We’d write these posters with words on them like “Pace” and “Attack” and hang them in his dressing room area. It was all part of getting in that zone with him. I think a lot of life was happening to him at that time. As he was growing [as a comic], I think he was getting so much stronger and so much more confident. You have to be; you can’t be tackling material that crosses the line that far and not be 100%. You’ve got to commit.

Let’s talk about the actual shooting of the special. How did you decide which performance to film?

Chanley: Chris wanted to be close to Washington D.C. to be with a very urban audience, but not necessarily a wealthy D.C. audience. He wanted regular American people there. So we found this little theater [the Takoma Theatre] that was not a state of the art venue at all. There wasn’t even a dressing room per se. There was one little room backstage where Keith designed that opening shot where you would see him come out of the door and along the back of the stage. That was actually a storage closet! Not a dressing room. We put his name on it, so it looked like he’s walking out of a dressing room backstage. And it was only a 500-seat theater. People think it was a much bigger venue because of the directorial style. It was actually very intimate.

We typically would tape two shows in one night. If you separate it into a two-night shoot, what’s going to happen is that you’re going to get a completely different performance and completely different audience. Whereas if you shoot two in the same night, the performer has a much similar energy in both tapings and the audience often is similar, too. There was a rainstorm that night that made it a little insane, because we had put up a VIP tent for anybody from HBO that was coming to the show and the tent got muddy. I remember looking at the sky and going, “God is telling us something. He wants us to know that something real big is happening here, and if we get through it, the show will be remembered.”

Were there any flubs or mistakes that you had to cut around while crafting the final version?

Truesdell: No. You can tell it’s pretty much straight through because he’s pacing back and forth, and if it was edited down, he’d be in a different place on the stage. But it’s smooth.

Chanley: He’s like a freight train, and once he’s off and running, it would be odd for him to stop. Even if the storm had taken all the power out, he’d just keep going. But that’s why you tape two shows in case something is off or if you have to dub in the timing of a bit if they don’t nail it as completely as they have in the past. Typically, you try to use all of one performance, and just fill in with the second show here and there. I believe the special is mostly the first show; he went out there and nailed it. He was ready.

Obviously, the most famous segment of Bring the Pain is the “N—– vs. Black People” routine. Did you know going in that that would be the show’s crescendo?

Chanley: That was probably the most cutting-edge statement in there, the one no one would have been expecting to hear. The black people in the audience were laughing because in those times, that’s not something that anyone would have even been thinking. I had heard that material in the Comedy Store really late at night, and the next day I dragged Keith into my office and said, “You are not going to believe what we’re about to do. We’re about to put words out into America that have never been uttered before.” We couldn’t pre-determine how the audience would react, so we were prepared, camera-wise, for anything. They could have just gone silent and stared at him, you know?

Truesdell: Then we’d have been in a whole different world, because we didn’t sweeten our specials [with a laugh track]. I had to be ready to go wherever the audience took us.

Chanley: But the crowd received it well, and it unfolded in such a big, loud way. Keith looked at it very calmly, just to make sure he’d captured it. That’s where live directors really shine — if they have the gift to step out of themselves. A lot of other directors would have got caught up in the energy and done a lot of fast cuts. But he stayed Mr. Cool and captured what was happening.

Given the nature of the material, did he express a desire to have a black filmmaker direct the special at any point?

Chanley: Chris just wants things to be the best they can be. At the time, I think we were known as being the best at what we do. We had a really good creative bond with him, and it’s very easy to work with people when they know what they want. What resonated with him is that we care so much about him. He trusted that we’d fight to make sure that everything was great. He’s so intuitive and reads things extremely well. Along those same lines, he’s also extremely supportive of his community. I know that when we shot Bigger & Blacker [Rock’s 1999 follow-up to Bring the Pain], we filmed it at the Apollo Theater. That was very important to him.

Jumping ahead to Emmy night, you were nominated in the Outstanding Variety, Music or Comedy Special category opposite the Tony Awards, the Academy Awards, a Bette Midler concert special, and George Carlin’s 40th anniversary comedy tribute. Did you have any confidence you were going to win?

Chanley: I think we were just sitting there smiling, thinking, “What the hell are we doing here?” [Laughs] We knew Chris was brilliant, but we had no confidence we would win. We didn’t even know it was eligible for an Emmy! That’s how out of touch we were. When we won, Chris Rock, his manager Michael Rotenberg, our former partner Tom Bull, and myself went up to the stage. Chris did all the talking; we just stood behind him, shaking. I don’t think he had anything prepared. He had also been nominated for and won Outstanding Writing for a Variety or Music Program, so he won two Emmys that night. Him winning for writing was a no-brainer award, but for the show to win overall was a “Wow” thing. Those statues are heavy! You carry that around all night, and you have a sore arm the next day.

How did the special and the Emmy win impact your career?

Chanley: We thought, “We are solid.” But our phone didn’t ring at the office for, like, two months! Agents would be telling us that everyone was afraid our rate would be too high. That kind of smoothed over, and people started taking meetings with us because other comics respected Chris Rock so much. And then Bigger & Blacker got six Emmy nominations, including Keith for Outstanding Directing for a Variety or Music Program. Personally, Bring the Pain gave us a bucket load of confidence that we were in the right place at the right time. If you want to Oprah the statement, our mission in life — we were doing it. [Laughs] And we still feel like giddy children that we have those statues in our office. They’re very gold, very bright, and very shiny.

What are your feelings about the current state of comedy specials? Netflix is a major player these days, for example.

Chanley: The last comedy special that we produced and directed was Craig Ferguson’s Does This Need to Be Said? for EPIX in 2011. So the state of stand-up comedy for us would be that we don’t recognize it at all. Keith ended up being a director on Everybody Loves Chris, and I produced the first two seasons of Curb Your Enthusiasm, so we’ve branched off into series work and things like that. Our talent isn’t in the [stand-up comedy] arena anymore. What we were excellent at is no longer necessary to the way they capture and air stand-up comedy now. It’s a lot quicker, and a lot less expensive. We’d spend months on a special following the comic, observing the preparation and how their act would evolve over that time.

Truesdell: I don’t know if they do that anymore. I don’t think they do. Plus, back then specials like Bring the Pain and Bigger & Blacker motivated people to purchase HBO to watch it. It was a really big deal; people flocked to it and it was reviewed. They still call them “specials,” I guess, but I don’t know how special they are.

Would you come out of your stand-up comedy retirement if Chris Rock asked you to do his next special?

Chanley: Only for our beloved Chris Rock would we do anything. [Laughs]