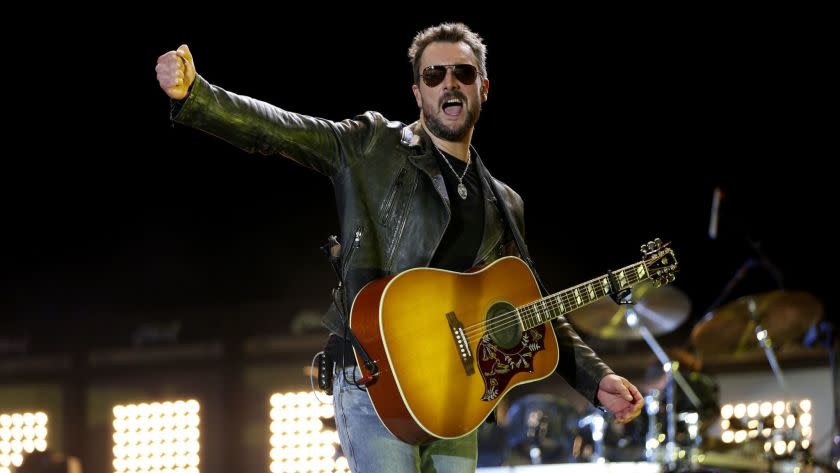

Eric Church never wanted to sing the Super Bowl national anthem. Then came the Capitol riot

Before Jan. 6, Eric Church had little to no interest in singing the national anthem.

“I’ve avoided it forever,” the country star says. “It’s an incredibly hard song to sing. And I’m not a vocalist — I’m a stylist. Somebody like me, you take some liberties with it, then you’ve gotten too far away from the melody and suddenly you’re a communist.

“Honestly, there’s just more to lose than to gain.”

Yet last month’s storming of the U.S. Capitol changed Church’s thinking about “risk versus reward,” as he puts it. So when the NFL reached out a few weeks ago with an unexpected invitation — would Church like to perform the anthem with the acclaimed soul star Jazmine Sullivan at Super Bowl LV? — he did what he always said he wouldn’t: He said yes.

“With what’s going on in America, it feels like an important time for a patriotic moment,” says the 43-year-old North Carolina native known for yearning but muscular hits like “Springsteen” and “Give Me Back My Hometown.” “An important time for unity. The fact that I’m a Caucasian country singer and she’s an African American R&B singer — I think the country needs that.”

On Sunday the two artists will collaborate in public for the first time before the Kansas City Chiefs and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers face off in Tampa — the same Florida city where Whitney Houston gave an iconic rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner” 30 years ago.

Overseen by veteran musical director Adam Blackstone as part of Roc Nation’s deal to shape the NFL’s musical offerings, the performance will be only the second anthem duet at the Super Bowl, following Aretha Franklin and Aaron Neville’s joint reading in 2006. (Other acts set for Sunday’s game include the Weeknd, who will perform at halftime, and H.E.R., who will sing “America the Beautiful.”)

In an email, Sullivan said she admires the “richness and grit” of Church’s voice and is “excited to blend our styles to create something original and new.”

For Church, named entertainer of the year at November’s Country Music Association Awards, the Super Bowl gig comes just as he’s announced the upcoming release of three studio albums — “Heart,” “&” and “Soul,” each due in April — that he recorded last year with his longtime producer, Jay Joyce, during a sojourn in the mountains of North Carolina, far from his usual setting in Nashville.

Were you familiar with Jazmine Sullivan prior to this?

I’d heard her name but I hadn’t really dug in. Roc Nation sent me her new project, “Heaux Tales,” which I dig — kind of a concept album with different voices and different female perspectives. Then I did more of a dive, and God almighty she is good. Unbelievable vocalist.

Have the two of you started formulating your rendition?

We’re doing that now. I’ve not met her in person; we’re both going down to Tampa midweek and we’ll get together several times. I know I want to play guitar. And we’re keeping it based around the melody. Basically, if I can stay out of her way, we’re golden.

It’s not common to see a duet.

Right, and keep in mind that neither one of us are gonna be in our natural key [laughs]. If you do it by yourself, you say, "Here’s the key and here’s how you do it." But when you’re in a duet, I’m giving, she’s giving — that’s the way that works. But that’s kind of what spoke to me. We’re unifying. And it’s a time in our country when we have to do that.

You said you agreed to do this after the Capitol riot. What were you thinking as you watched the events of that day?

I feel like in this country, we’ve given up the common ground. When I’m at a concert, I’m not thinking about how many people there are Republicans or Democrats. But that’s how you win elections — you have to create the division, to rile up a base. And because of COVID, we’ve lost the things that used to unite us: concerts, sporting events, trips to Vegas with the boys. I can tell you from the concert standpoint, the longer we go without people being able to put their arms around the person next to them and have a moment of communion, it gets more tenuous and more dangerous. And I think the reality of that is what happened at the Capitol.

It’s certainly the case that isolation hasn’t helped anybody. But the bigger problem seems to be getting people to accept one set of shared facts.

And I don’t know how that happens. But what I know helps is being together and talking with those people. Being in a room. That’s the biggest thing now — we’re not in rooms together, we’re not around each other. I think when we do an autopsy on COVID, we’re gonna realize how much mental health matters. We’ve been so focused on the physical because we’ve had to be. But the emotional and the psychological — it’s gonna matter for a while.

Has it been hard for you not to play?

Yeah. I’ve been able to keep all my band and crew and all my guys — we’ve not even cut salaries, and I’m proud of that. But it’s been an incredibly strange and trying time, and I know I’ve got it a lot better than most people. But I’m hopeful. I didn’t feel as hopeful late last year but I like where we’re heading. I think 2021’s gonna be a redemption year and 2022’s gonna be the s—.

How much of that optimism has to do with Biden winning? With a change at the top?

I don’t know. The vaccine is kind of what it was for me — not just the vaccine but the implementation. I watch the daily count obsessively, and nothing’s gonna happen until we get it in arms. But now we’re starting to see a plan going forward that looks effective, looks like it’s gonna work. And that of course was a little bit because of the change.

Your new albums — you made them during lockdown or before?

We recorded these in January and February of 2020, then the world went to hell. We forced quarantine on ourselves for creative reasons.

Why?

Well, I didn’t know what was coming [laughs]. Honestly, Jay and I had made six albums together, and if you look historically, that’s when you start to try to move on from the same producer. Uprooting everybody was the only way I knew to find that uncomfortable, nervous energy that I think has always made our best albums together.

Does each disc have a distinct sound or theme?

A theme, yes — you’ll feel them separated as you listen. But the sound is the sound. And the reason the sound is cool to me is because we were basically in a restaurant that we turned into a studio. This is Banner Elk, N.C., where I go in the summertime and stay with my family; we have a house there. And there’s a restaurant we’d go to, whole thing made out of reclaimed barn wood. Every time I walked in, I’d say to my wife, “This would be a hell of a room to record in.” So we just brought everything in there and set up shop, Big Pink-style.

You’re booked to play a number of festivals later this year. Think they’ll happen?

I think it’s a fourth-quarter deal for me, but depends on what state the festival is in. I wish we were in a place right now where we could use concerts to vaccinate people. But I feel good. There’s so much antivax s— that goes around, but I’m seeing less of that now. People just want out. Somebody asked me if I’d take the vaccine. I said I’d take it in the eyeball to go strap on a guitar.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.