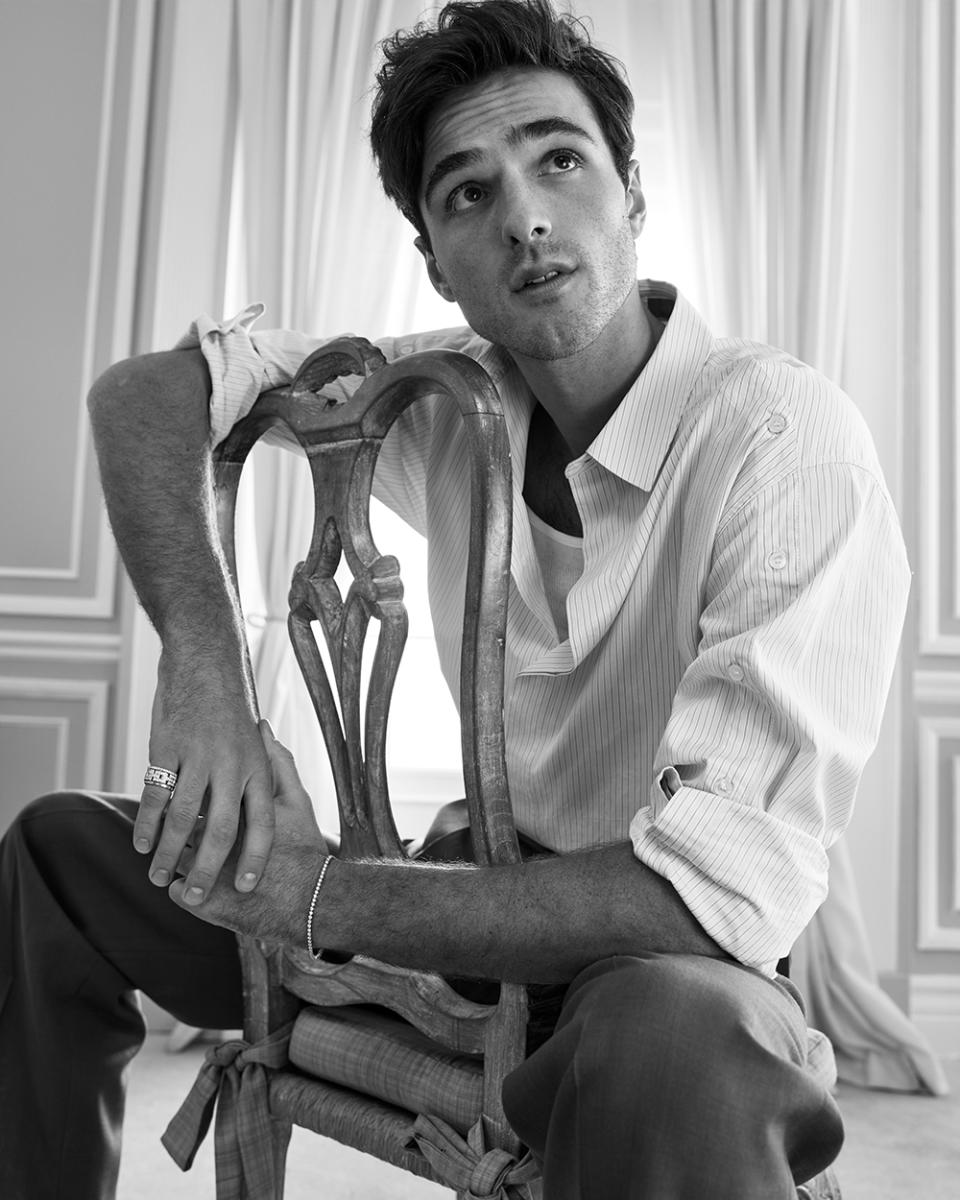

‘Euphoria’ Stars Jacob Elordi and Colman Domingo Finally Break Big at the Movies: ‘I Feel the Most Free in My Career I Ever Have’

For two seasons, Colman Domingo and Jacob Elordi have passed each other on the set of the megahit HBO drama “Euphoria” without ever sharing a scene. That’s why Domingo, who won an Emmy for guest actor in the show, describes this conversation as “an overdue coffee” — just without the caffeine kick. As the actors discuss the pressures of portraying historical figures — Domingo embodying Civil Rights leader Bayard Rustin as he plans the 1963 March on Washington in George C. Wolfe’s “Rustin,” and Elordi rendering the human side of Elvis in Sofia Coppola’s “Priscilla” — they realize another thing they have in common: They’re both mama’s boys.

In this Actors on Actors meet-up, they talk about those deep attachments, which helped them through shooting back-to-back films — Domingo flying from “Rustin” to the role of the abusive Mister in Blitz Bazawule’s reimagining of “The Color Purple”; Elordi getting ready for “Priscilla” while still shooting Emerald Fennell’s sexy psychological thriller “Saltburn.”

More from Variety

JACOB ELORDI: It’s wild that we’ve barely crossed paths, which is kind of a gift too; I can sit back and marvel at your work because I’m not there seeing how you work. I was always a little intimidated on set every time I saw you, because you’re about your craft. I was at home last night doing research like I was about to play you in a movie or something because I was so nervous. I was like, “I need him to understand that I care the same way he does.”

COLMAN DOMINGO: But that’s what I see in you, to be honest. As I started to do the deep dive on the choices you’ve made, I see someone who’s crafting characters in a very deep, extraordinary way. I saw “Priscilla” and “Saltburn” — very different performances. That’s not easy.

ELORDI: You’re the actor’s actor. What’s that like, working so diligently — and I don’t want to say “in the shadows,” because I don’t want to underplay it. But it feels like you cultivated your craft without a pat on the back or accolades.

DOMINGO: That’s exactly it. The strangest thing is to sit across from you knowing that I’ve been in the performance space longer than you’ve been on the planet. My career has been about 33 years — I started when I was 21; I’m 54 — and my whole journey has been about being a multi-hyphenate. I started out as an actor, but I was always interrogating the work as a writer, as a director and then as a producer. I always felt like the only way I could have some agency in this industry is to own it and to do it myself. I stayed under the radar. I’m having a moment in my career, but it’s a moment that has been built for many years and many ups and downs. I’m a journeyman. I went where the work was — regional theaters, London, Off Broadway, black box, you name it because I just wanted to work.

You have this incredible fan base. Do you still feel like you have freedom and liberty to almost go the opposite of me and play in some sandboxes that are not so shiny?

ELORDI: I feel the most free in my career that I ever have. When I was 15, I was at an all-boys Catholic school. I was deeply unsettled and didn’t know why. In theater class, I read “Waiting for Godot.” I didn’t understand it, but something changed. Everything that I believed in just went out the window. I became an observer. Acting and performance and story became my church. I worked 24 hours a day, devouring everything that I could. My personality changed. Then I started making movies, and it went away. For two or three years, I was in a scramble. Even during “Euphoria,” I was trying to catch it and find it again, because all these rules and ideas start getting put on performance.

DOMINGO: It becomes about the product.

ELORDI: My whole thing was about losing myself in the performance. But now I’m bringing “Jacob Elordi” to a performance, which is such a heady, trippy thing. I’ve been in the process of trying to shake it as it grows bigger and louder. But strangely enough, I’m in a place now where I feel free.

With you — and I have an idea because of something you just said on a talk show — when did you learn that you could do what you do? You said something about your mother in the interview.

DOMINGO: Something like, “Where will we be without the dreams of our mothers?” I’m a mama’s boy.

ELORDI: Me too. When you said that, man, I started crying. I take my mom everywhere with me, but I realized in that moment that every performance I give is an extension of the things she wanted for me. How did that push you? Because she’s the only reason why I do what I do.

DOMINGO: My mom was my best friend. She was a dreamer. She was spiritual and lovely and believed in the good of mankind. I was shy, bookish, awkward, skinny and not cool at all, in West Philadelphia. My mother put me in this summer camp. We had some acting classes; it got me outside myself. Later, I took acting in college because my mother said, “Take something just for fun. Just for you.” One of my teachers took me aside and said, “Have you ever thought of acting as a profession?”

I lost my mother in 2006. I was devastated and told my friend, “What am I going to do with all this love?” She said, “You’re going to pour it into everything that you do.” I started to create work in a different way — it’s even more meaningful and intentional. It matters if other people love it or respond to it, but it’s more about being true to what my mother gave me.

Tell me about your mom.

ELORDI: My mom is the same — unconventional in the way that she would support me in doing something fun. “Don’t do math. Don’t do science. You should do this other thing.” She suggested that I do theater; she was the first person to tell me that maybe my gift is not athletic, maybe it’s in the arts. She gave me the liberty to breathe.

I like what you said: “What am I going to do with all this love?” Not all this grief, not all this sadness. And that comes out all the time, not just in your work, but in the way you carry yourself. Your performances are an extension of how you move through the world, and it’s noticeable. I’m just damn happy that people are noticing it now.

DOMINGO: Thank you, man.

ELORDI: I felt that when I watched “Rustin.” I felt like a fool because I turned it on and was like, “I know nothing about this man.”

DOMINGO: Many people don’t.

ELORDI: Your transformation was everything. Starting with your voice. There’s not many videos of him talking, but you nailed it. You also brought something else to it that was your own. Tell me about it.

DOMINGO: I thought it was such a travesty that we didn’t know anything about Bayard Rustin, his story and his influence on the Civil Rights movement. Then the idea that someone like President Obama and Michelle Obama were making sure this story is told, there’s a great weight and responsibility. You want to do all you can to show a living, breathing soul, an ordinary human being trying to do something extraordinary. It’s my first leading role in a film. I wanted to do all that I could to get the nuances of his body, his voice and his mind, but also his soul.

There’s an alchemy that happens after you’ve done arduous research and learned everything you could. Now you just have to be in the moment, listen and respond. Then you’re like, “OK, I have to trust that the divine will reside.” That’s something I witnessed with you. Elvis is iconic, and now you have an experience with this beautiful filmmaker Sofia Coppola that showed another dimension. Usually, you see the showman. What’s your approach?

ELORDI: I was shooting “Saltburn” at the same time.

DOMINGO: Wait, what?

ELORDI: I got the roles on the same day. I’d shoot “Saltburn” in the day, and then I’d go home to my hotel — I was there for months, so I’d covered every inch of the wall in photos of Elvis and Priscilla with the same thing in mind: “If I can absorb all of this, I’m not even going to think about it. I’m just going to live in it.” There’s no way I’m going to play Elvis Presley unless the divine comes in. Because you can learn how to dance, you can do your best to learn how to sing, and you can curl your lip thing and do those things. That’s all mimicking, copying and letting it get into your bones. But I realized really quickly with Elvis that there’s a deep spiritual element to him.

Something happened on the last day, when he says to Priscilla, “Maybe another time, maybe another place.” It’s an emotional scene. I’d been sitting with it and hadn’t really thought about it. And I just started weeping in this hotel room in Vegas. Philippe [Le Sourd, the film’s cinematographer] set up red lights outside the window so that they were a beating heart that was slowly dying, like his heartbeat going out. I looked at Cailee Spaeny, my co-star, and said, “They killed this boy.” That was the divine coming in.

DOMINGO: What’s the biggest challenge you had playing Elvis?

ELORDI: I didn’t want to do him the disservice of playing “The King” that the world had made, because that’s what hurt him so much. It was my job to not play into his fame but play him as a victim of it — to play him as a man who was suffering. Because with great figures, we never really think of them as suffering. In pictures, you see bits and pieces if you look closely enough. We act like it’s all fine that he died the way that he did, but it’s not. A little boy died. The weight of that sat with me. I never wanted to throw my hips around and curl my lip and smile and be sexy, because the way that Priscilla sees him is a man who’s suffering. And she loves this man.

DOMINGO: I did “Rustin” and then “Color Purple” right after — did you just move whatever energy and transform that with your character in “Saltburn”?

ELORDI: I was playing what I describe as the personification of sunlight, which is Felix [in “Saltburn”] and then went into Elvis. But Elvis was a nice sedative, and I was glad that I finished on that. Because whatever the job is, even if it’s unrelated to you, in the craft you’re expressing something, even if you don’t know it, that’s going on inside. Obviously, I’m not Elvis Presley at all. But there were elements that were relatable, and I got to get all these things out while playing him. When we finished, I kind of [he exhales]. It didn’t stick with me. It didn’t hang with me. It felt like he had come to give me this lesson.

What about you shooting them so closely? Because you went from Rustin to the devil.

DOMINGO: I love to think, “What did I need at the moment from these characters? What are they teaching me?” Rustin was teaching me leadership, conviction and intention. When I moved into “The Color Purple,” I was looking into the darkness. People see [me as] this happy-go-lucky person, but I have everything that Mister has in me. I just make a choice every day to live in the light. But I could go to the dark place too. And that’s human. That’s our job. I have no intention of just playing heroes. I love the opportunity to play someone Colman feels is despicable.

ELORDI: [Mister] doesn’t have the means to act the way you and I would act in that situation because he hasn’t been given them. He hasn’t been given the light from his mother, the same way that we have. And that’s interesting as an actor. More interesting than running out and being like, “Today, I’m a hero.”

Variety Actors on Actors presented by “Saltburn.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Solve the daily Crossword