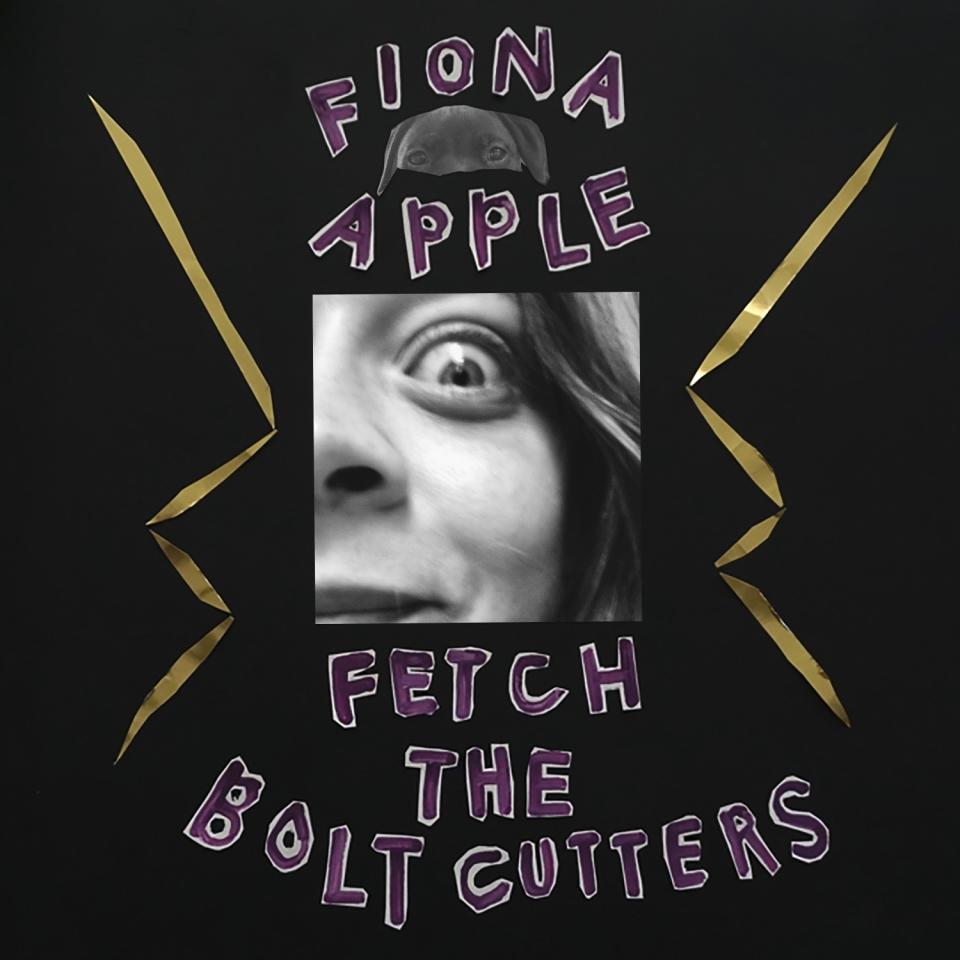

Fiona Apple's stunningly intimate new album makes a bold show of unprettiness

“Fetch the Bolt Cutters” is Fiona Apple’s third consecutive album with a title to suggest that one of pop music’s flesh-and-bloodiest songwriters has cold, hard machinery on her mind.

Eight years before this one, in 2012, there was “The Idler Wheel …”; seven years before that one, in 2005, there was "Extraordinary Machine.” Certainly you can hear evidence of Apple’s fixation in the records’ highly percussive arrangements, which often emphasize quasi-industrial rhythms — complicated beats tapped out on drums and cans and pieces of scrap metal — over the type of swooning melodies that defined early hits like “Criminal” (recently used to show-stopping effect in “Hustlers”) and “Shadowboxer.”

But taken together the titles also get at the way Apple, 42, appears to regard her music as a device to process trauma: “I know none of this will matter in the long run,” she sings in “I Want You to Love Me,” which opens the new album, her fifth overall, “But I know a sound is still a sound around no one.” Render the pain just so, her thinking seems to go, and you might contain its ability to continue hurting or staining you — like a dishwasher or a rock tumbler or an engine burning up toxic fuel.

Not that her interest in gadgets extends to an assembly-line approach. In the near-decade since “Idler Wheel ...,” the singer has spent a decreasing amount of time outside her home near Venice Beach, even as her influence has spread among younger artists such as Lana Del Rey, Billie Eilish and King Princess; she recently gave a rare interview to the New Yorker in which she described how tortuous she found the idea of re-entering the fray to promote a new project.

Indeed, you have to wonder if she elected to release “Fetch the Bolt Cutters” on Friday — months earlier than she’s suggested unspecified suits wanted her to — because the COVID-19 pandemic would provide some cover for the publicity she was already planning to avoid. (The album’s title quotes a bit of dialogue from the British crime drama “The Fall” in which Gillian Anderson’s character calls for the tool required to open a locked door.)

The result of Apple’s self-imposed social distancing is the stunning intimacy of the material here — a rich text to scour in quarantine. Her idiosyncratic song structures, full of sudden stops and lurching tempo changes, adhere to logic only she could explain, which forces you to listen as attentively as though a dear friend were bending your ear; thus dialed in, you notice the array of close-miked textures in the music, much of which she laid down at her house over the past five years with a cozy group of collaborators including drummer Amy Aileen Wood, guitarist Davíd Garza and bassist Sebastian Steinberg (familiar to ’90s alt-rock fans from his stint in Soul Coughing).

In “Heavy Balloon,” about the difficulty of keeping the weight of depression aloft, Steinberg’s slithering bass is an almost tactile presence, while the album’s memory-jammed title track ends with the sound of Apple’s beloved dogs barking their heads off — a bug of home recording that she turns into a feature.

Apple delivers that number in a breathy, slow-and-low mode that can harken back to her sultry early work. But mostly she seems determined to display the frayed edges of her voice, as in the swaggering “Under the Table” and “Newspaper,” which doesn’t have a tune so much as a furious spray of loosely connected notes. In “Relay” and “Rack of His” she’s essentially rapping, piling syllables on top of each other with thrilling abandon; in “Ladies” she repeats that loaded term so many times that it starts to shed its meaning.

Basically, you’d need to go back to the later parts of Nina Simone’s catalog to find another pop vocalist as eager as Apple is to make such a show of unprettiness — a shared result, perhaps, of exiling oneself from a business you can’t stand.

As for her lyrics, Apple has never cut closer to the bone: “Well, good mornin’, good mornin’,” she sings in “For Her,” “You raped me in the same bed your daughter was born in.” Yet as unflinchingly personal as this music feels, Apple isn’t always mining her own troubled autobiography as she was widely assumed to be doing in her teenage-phenom days. “For Her,” she told the New Yorker, was actually inspired by watching Brett Kavanaugh be confirmed to the Supreme Court; in “Newspaper” she identifies with a woman unfortunate enough to have ended up with her ex.

“I watch him let go of your hand, I wanna stand between you,” she tells the woman over a clanking punk-cabaret groove. She’s seething but she’s empathizing — a feeling machine operating at full tilt.