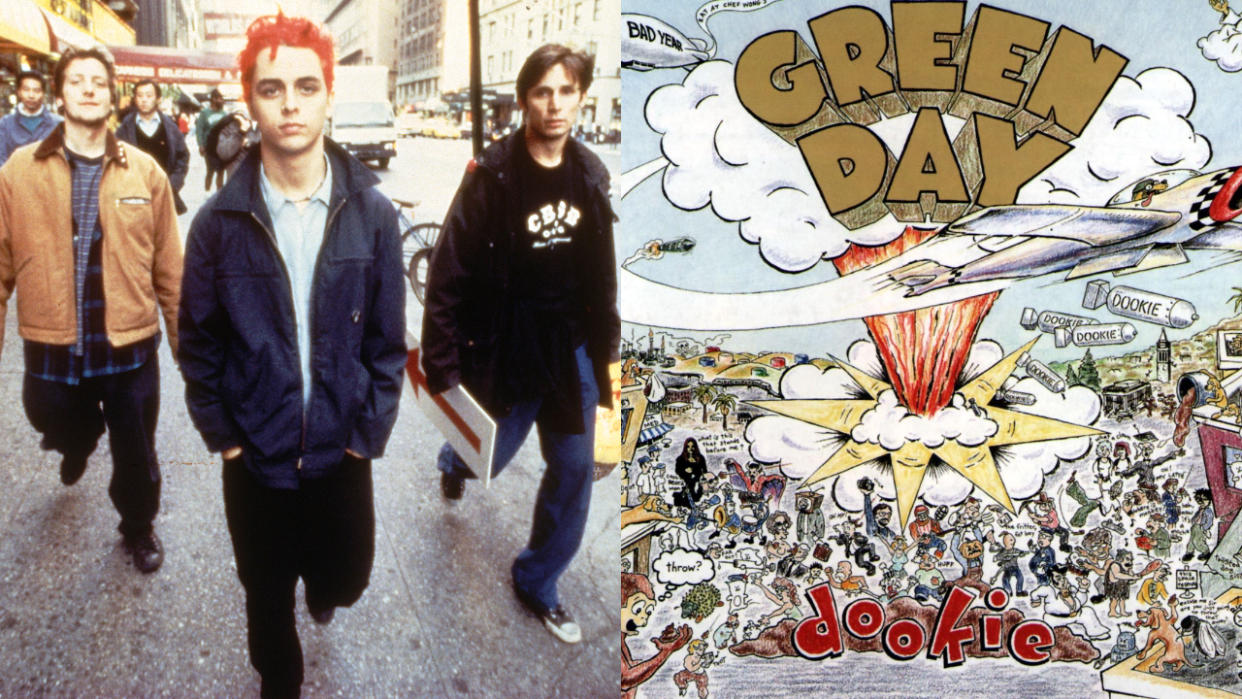

"We had a fear of failure and a fear of success at the same time": How Green Day smashed through punk rock's glass ceiling to sell 20 million copies of Dookie

For Green Day vocalist/guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong, the 25th anniversary celebration of Woodstock festival ceased to be a festival of peace, love and understanding when he spotted his friend Mike Dirnt spitting three broken teeth and a mouthful of blood onto the stage.

Security had the bassist pinioned on the stage floor, his blood and sweat-stained face slammed hard against a wedge monitor. Dropping his guitar, Armstrong dived in to rescue his friend, and punches rained down upon the pair of them. As a punk rock band, the notion of playing Woodstock II - a faux-nostalgic celebration of the original hippie festival - had always been something of a joke to Green Day. But right now, that joke didn't seem so funny anymore.

In truth, Woodstock II, held over the weekend of August 12 -14, 1994, and billed as 'Three More Days Of Peace And Music' had been descending into anarchy long before Green Day (literally) hit the stage. Days of torrential rain had transformed the 843-acre Winston Farm site in Saugerties, New York into a mud bath. Campsite facilities for a quarter of a million people who had paid $135 to attend were woefully inadequate, food and drink prices verged on the illegal, and around 100 people per hour were turning up to the site's two field hospitals, suffering from sprained ankles, hypothermia or both.

Peering through the tinted windows of the stretch limousine that had been sent to ferry his van to the festival - an unexpected consequence of Green Day's third album Dookie having already passed the 500,000 sales mark in the US alone - 22-year-old Billie Joe Armstrong observed the mud people rolling around in the filth with a mixture of incredulity, amusement, and horror.

"It was the closest thing to total chaos I've ever seen in my life," he would later admit. "I saw police and guards throwing down their badges, quitting on the spot saying, 'I can't do this anymore!' Technically, it was a human disaster."

Green Day had been allocated a 3pm slot on the site's South Stage on the festival's final day. The organisers' decision to preface the Californian trio's much-anticipated performance with three hours of WOMAD acts was, at best, short-sighted, and despite Peter Gabriel's repeated pleas for the crowd to show the African musicians onstage some respect, chants of 'Green Day! Green Day!' rang out throughout sets by Hassan Hackmoun and Geoffrey Oryema.

Under the circumstances, Billie Joe Armstrong's decision to open Green Day's 50-minute set with a song called Welcome to Paradise was mischievous, wonderfully inappropriate and not a little provocative, the blue-haired frontman taking great delight in teasing the weary, sodden, largely collegiate crowd with the opening line, "Dear mother, can you hear me whining?"

"Look at you dirty motherfuckers," the singer laughed when the song zipped to its conclusion, before asking the crowd do a 'Mexican Wave'. He then introduced One Of My Lies from his band's 1991 album Kerplunk as a song "off one of our records that no-one has."

As the band were about to launch into Chump, the third song on their set-list, the first clump of mud was thrown in their direction. "Oh shit," said Armstrong. "It's kaka. Poopoo. Shit. It's shit."

With the benefit of hindsight, calling out "Nice shot!" when the first lump of mud struck Mike Dirnt may not have been entirely advisable. Nor was Billie Joe dropping his trousers and urging "assholes" in the crowd to throw more. By the time Green Day attempted to close their set with Paper Lanterns, the stage was covered with mud, as was Armstrong's guitar, which he soon abandoned in favour of standing at the lip of the stage hurling dirt back into the audience.

"This isn't love and peace," he shouted, "it's fucking anarchy."

This isn't love and peace, it's fucking anarchy

As the stage's security team took cover at the side of the stage, fans began to crowdsurf over the barriers and run onto the stage. Seeing one teenage girl dragged away by her hair, Mike Dirnt came to her aid, and was sent crashing on the stage by security for his trouble. Which is when the most chaotic performance in Woodstock's history came to an abrupt, violent end.

The band were bundled offstage, and ordered to leave the area for their own safety. But their performance was the talk of the site. Even with Porno For Pyros, Bob Dylan, and headliners Red Hot Chilli Peppers - reportedly paid 1 million dollars for their appearance - still to play, the day belong to Green Day. And all across the US a TV audience of millions watching live on pay-per-view made a mental note to check out these weird kids with the green and blue hair the next time they hit a record store.

Not everyone watching was impressed, however. When Billie Joe Armstrong returned home to his apartment in Berkeley, California there was a letter from his mother waiting for him. Mrs Armstrong had indeed heard her son "whining" on TV and was disgusted by what she saw. Her son's performance, she noted, was "disrespectful", and "indecent".

"Were your father still alive," she wrote, "he would feel ashamed of what went down."

On February 16, 1989, one day before his 18th birthday, and one week before his band were due to release their debut album 1,039/Smoothed Out Sloppy Hours, Billie Joe Armstrong decided to drop out of Pinole Valley High School. All he needed was the assent of his teachers, and Armstrong would be free.

He made the rounds that morning with a glad heart: most signed his official drop-out slip without a word. One teacher, however, looked confused when presented with the sheet of paper. "Who are you?" he asked. Armstrong couldn't care less. He already had his own seat of learning, a place where everyone knew his name.

A former garage building located in North Berkeley, just over a mile of the local train station, 924 Gilman Street was Armstrong's home from home. Opened in 1986 by Tim Yohannan, the founder of militant punk fanzine Maximumrocknroll Gilman Street as the club was known was and is an all ages nonprofit venue for underground music. Run by volunteers, and operating a policy of booking only bands whose values aligned with the 'house rules' - no sexism, no racism, no misogyny - Gilman Street gave the East Bay's strays and misfits a sense of belonging.

"The kids who were here were latch-key kids," said Mike Dirnt, "so we learned [about] community, family, values... but also work."

Together with his classmate, Mike Prichard - aka Mike Dirnt - Armstrong would travel to the club from his home in the oil refinery town Rodeo every weekend, begging on Gilman Street for pocket change to score the meagre price of admission to see local heroes such as Isocracy (who featured future Green Day drummer Al Sobrante, aka John Kiffmeyer), Crimpshine and Sweet Baby. Dirnt and Armstrong were already familiar with the sound of punk rock: at Gilman Street, they saw the idea of punk put into practice.

"Every single weirdo and nerd and punk around the Bay Area would be there, and it was great," Armstrong told writer Ian Winwood for his 2018 scene history Smash! "Gilman was the first time I learned anything in my life. Before Gilman, everything I'd learned up until that point was bullshit."

In 1987, before either Armstrong or Dirnt had celebrated their 16th birthdays, they formed their own band, Sweet Children.

"We played everywhere, a bar mitzvah, someone's backyard, someone's bathroom. It made us a better band

"It was, Well, here's some kids with just as crappy equipment as we've got, and they're making great music, and playing gigs," Dirnt recalled." It really was a classic realisation of, Hey, we could do this!"

"We played anywhere and everywhere," Armstrong recalled, "whether it was a bar mitzvah, or someone's backyard, or someone's bathroom. Part of the fun and beauty of punk was three bands sharing one guy's amp, or seven bands sharing one drum kit held together by tape. We played every gig, wherever it was, and never cancelled anything. It just made us a better band."

It was this attitude which led Sweet Children to jump onto a high school party show that Gilman Street regulars The Lookouts were playing in a log cabin in the mountains of Mendocino County, 140 miles from the East Bay, in late 1988. Before the night was out, the band has been offered a record deal by Lookouts frontman Larry Livermore, co-founder of Lookout! Records.

Writing for Louder in 2015, Livermore recalled the precise moment he fell in love with the band.

"Billie Joe and Mike were barely 16-years-old at the time, but you’d have thought they’d been on stage all their lives," he marveled. "The ‘audience’ might have been five kids sitting on the floor in a candlelit cabin, but Billie treated them as if they were a packed house at Wembley Stadium.

"I was in awe. I’d seen amazing bands in my time – the MC5, The Stooges, the Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Ramones, the Sex Pistols, The Clash, to name a few – but these kids were already in that class, and this was only their third or fourth show ever.

"They finished their set and Billie walked over to me and shyly asked, 'So what did you think?'"

“I want to put out your record," Livermore answered.

A few months later, Livermore put Sweet Children in the studio to record four songs for their debut EP, 1,000 Hours. He was less than impressed when, two weeks before the record's April '89 release date, Billie Joe informed him that his band were changing their name to Green Day. Fortunately, Livermore still believed in their music. One year on, separated by a second EP, Slappy, Green Day's debut album, 39/Smooth, emerged on Lookout! The album's sound was raw, but the quality of Armstrong's punchy, poppy songwriting was evident through the tinny production. When Lookout! issued the group's second album Kerplunk, on December 17, 1991, it sold out the entire first pressing, 10,000 copies, that same day: by the end of '92, sales were north of 50,000. It was increasingly obvious to everyone in Green Day's circle that they were fast out-growing 'local hero' status. For Larry Livermore, listening to the record for the first time brought the realisation that "things were about to get real."

He recalled: “It would be a couple years before everyone knew what I had just realised, but in my own mind there could be no doubt: the band that had produced the music cascading through my headphones was about to become one of the biggest bands in the world.”

In the wake of Nirvana's phenomenal success with Nevermind, America's major labels acted quickly to cream off the best bands from the nation's most credible independent labels - Butthole Surfers, The Jesus Lizard and Girls Against Boys from Touch and Go, Jawbox and Shudder To Think from Dischord, Helmet from Amphetamine Reptile, Babes In Toyland from Twin / Tone - and punk was no longer a dirty word. The time was right to Green Day - now featuring former Lookouts drummer Tre Cool - to take their next leap into the unknown.

After five years of managing their own affairs, the band signed with their first management company - Elliott Cahn and Jeff Saltzman, who already represented Mudhoney, Primus and Melvins - and handed them a new demo to shop around. Warners, Geffen, Sony, and leading California punk label Epitaph were among those who liked what they heard. While the band made fun of the attention coming their way - Mark Hoppus of Blink-182 recalls a gig at San Diego's Soma club, where Armstrong mockingly encouraged the crowd to cheer as loudly as possible, so that the A&rR men in attendance would consider the band a worthwhile investment - they were far from naive when it came to business matters, and recognising their own worth.

"We held off for a long time," Tre Cool told author John Ewing. "We wanted to hold out until we got complete artistic control. We wanted to be the bosses, and not let somebody else tell us what to do. Of course, the first offer is bullshit, the second slightly less, the third still kind of sucks. We thought, Fuck this, it's our lives."

Reprise Records A&R man and producer Rob Cavallo was finishing up production work on the debut album by The Muffs when Green Day's demo was passed on to him. The son of music industry veteran Bob Cavallo, manager of Prince and Paula Abdul, he flew out to Berkeley to meet the band in the summer of '93.

We wanted to be the bosses, and not let somebody else tell us what to do

"I'll never forget what Green Day said to me - it was so cool - they said, 'We're going to be a great band. We're going to be a great band no matter what Reprise does for us," Cavallo recalled in 2005. "They knew what it took to be successful in the music business. They were like, 'We think we need to help of Reprise to help realise our potential: however, we're fully confident we're going to do it on our own anyway. So you're going to take the record that we make, and you're going to send it to radio stations for us. When they hear it they're going to like it, and they're going to want to play it'."

Cavallo got his men.

Green Day certainly weren't the first American punk band to sign to major but in the early '90s, taking the corporate dollar was still a contentious issue. That same year Chicago arts magazine The Baffler had published an article from former fanzine writer/Big Black frontman/studio engineer Steve Albini titled The Problem With Music, an acerbic dissection of the financial and philosophical ramifications of underground bands signing too major labels. In June 1994, Maximumrocknroll would borrow the final line of Albini's essay for a cover story attacking bands - Green Day among them - who they perceived had 'sold out' the scene. The cover line Some Of Your Friends Are Already This Fucked ran on top of a photo featuring a man with a gun in his mouth. Coming just two months after Kurt Cobain's death by suicide, the issue was the subject of heated debate in the punk community.

For Green Day, a more tangible consequence of signing to a major was that they were now excluded from playing Gilman Street, the trio bowing out with a 'farewell' performance on September 6, 1993. It would be 21 years before the rules were (temporarily) relaxed to allow them to play the venue again.

"In our eyes, going to major wasn't selling out," Armstrong insisted. "Going to a bigger indie would have been selling out. If we'dd gone to Epitaph - which is a label that wanted us, and a label I respect - I would have considered that more of a betrayal of Lookout! that us going to a major."

Work on Green Day's Reprise debut began at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley at the tail end of summer '93. The band may have had a proper budget for the first time, but they weren't going to slack off. With Armstrong using a 100 watt Marshall amp borrowed from Cavallo, who served as their producer, the trio laid down 17 tracks in just 19 days, working 12-hour days to commit the songs to tape: vocals were completed in just two days.

Dookie was released in America on February 1, 1994. It entered the Billboard 200 chart at number 141, a position that seemed to make a mockery of glowing pre-release reviews. Filled with melodies, hooks, knowing ennui and rushes of hormonal teenage angst, it was a punk album with a pop heart, an album about growing up without giving in to societal pressures.

Though many of Armstrong songs are written from the perspective of a teenage no-mark - "I write a lot about being a loser because I was conditioned to think that way" he once admitted - a fierce intelligence simmered beneath the surface slacker attitude. Welcome To Paradise, originally released on Kerplunk, celebrated the dubious delight to a former hostel/brothel on West 7th Street in Oakland that the 17-year-old Armstrong had called home after fleeing the parental nest. Longview was a slacker anthem, about masturbation, bong hits and daytime television. Pulling Teeth and She were bittersweet love songs filled with images of violence and desperation. There was darkness too behind the outwardly perky Having A Blast, a tale of a disturbed young man so alienated from the world that he chose to exit it as a suicide bomber: "No-one here is getting out alive," runs the chorus. "This time I've really lost my mind and I don't care."

"We knew when we went into make Dookie that it was going to be a harder-edged album," Armstrong acknowledged, "but we felt we were going with a label that would allow us to make records even if we weren't - quote unquote - commercially successful."

The first single chosen to introduce Dookie to the world was Longview. The song's video, filmed in the basement of the apartment on Berkeley's Ashby and Telegraph Avenue that Armstrong shared with Tre Cool, their respective girlfriends, and three others, saw the singer trashing the same room in which he had written the song. It had the energy and attitude of Nirvana's Smells Like Teen Spirit video, a comparison not lost on MTV programmers. By the summer of 1994, the single had crept to the top of Billboard's alternative rock songs chart.

At the start of August, Green Day replaced Japanese noise-rock troupe Boredoms as the main stage openers on Lollapalooza, warming audiences up L7, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, A Tribe Called Quest, The Breeders, Beastie Boys and Smashing Pumpkins.

"When we were booked on that tour, we were really nobody," Billie Joe Armstrong recalled, "but it was then that I could feel that something was happening. We were the first band playing, on at noon in these big sheds, and people were bum-rushing the show, bum-rushing the gates and turnstiles to come see us play. By the time we were finished on that tour, we were outselling the bands who were headlining."

Green Day hysteria brought with it new problems. Two days before the band were due to play Woodstock II, at a show at the Lakewood Amphitheatre in Atlanta, Georgia. Armstrong asked the audience - specks on the horizon on the grassy hill behind the corporate setting - to get down the front to dance to Welcome To Paradise. In the frenzied rush to the stage, a female security guard had her arm broken, and with a threatened lawsuit hanging over their heads, management feared that things were in danger getting out of control for the trio. They jetted off to Woodstock promising Cahn and Saltzman they'd be on their best behaviour...

In the immediate aftermath of the festival, sales of Dookie skyrocketed, passing the million sales mark within weeks. A second single from the album, Basketcase, released two weeks ahead of Woodstock II, reached the top of the Billboard Modern Rock chart that same month and stayed there for five weeks. The trio were fast becoming a phenomenon. When the band were booked by Boston alternative radio station WFNX and the Boston Phoenix newspaper to play a free concert on September 9 at the Hatch Shell, an outdoor theatre on the city's Charles River that traditionally hosted the Boston Pops Orchestra, organisers expected 5,000 kids to turn up: unofficial estimates on the day put the number present at 10 times that, and the gig was pulled for safety reasons, leading to riots in the streets. Sitting in his Boston hotel room later that evening, Armstrong and his childhood sweetheart/wife of two months, Adrienne watched the riots unfold on a local news programme. "Who is this Green Day?" the news announcer solemnly intoned, "This punk band from the wrong side of the tracks?"

"It was just so funny to watch," said. Armstrong. "Like, Holy shit!"

A year that began with Green Day playing a gig in the kitchen of a friend's house in California ended with them playing a headline date at the 16,000 capacity Nassau Coliseum on December 2, and a two-song performance on Saturday Night Live on December 3: 1995 would start with the trio on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine, with a Billie Joe Armstrong quote reading, "I never thought that being obnoxious would get me where I am now."

As Dookie turns 30, its estimated worldwide sales are 20 million and counting, a number destined to leap higher when the band play the album in full on their upcoming stadium tour.

Looking back upon the record's phenomenal success with writer Ian Winwood, Billie Joe Armstrong reflected, "I do remember that we had a fear of failure and a fear of success at the same time. But I really didn't know what would happen. I was expecting the best and expecting the worst... I thought, Well, if we're gonna do this, let's make it as big as possible, or else let's go down in flames. And there was fear when it came to both of those things. But this is what we signed up for. We wanted to do this for the rest of our lives, and that's what we've done."