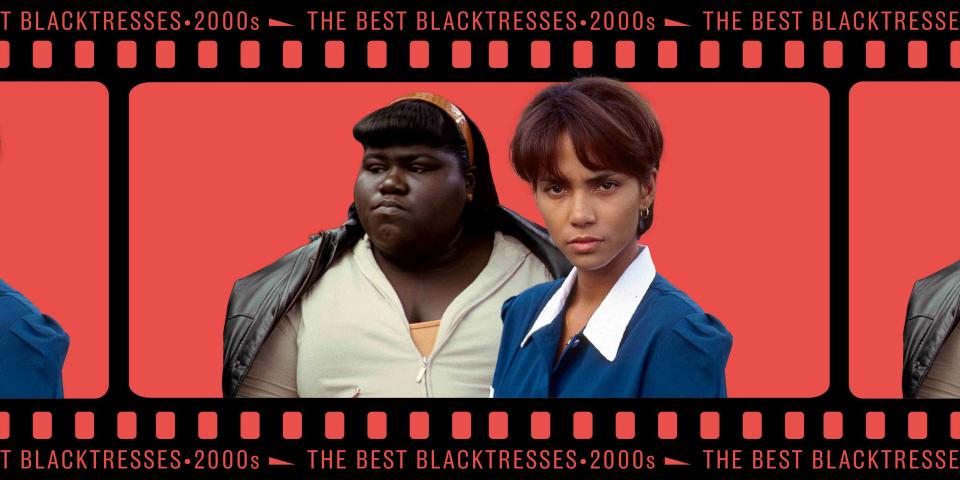

Halle Berry wins the Oscar, fulfilling Dorothy Dandridge's promise, and introducing Gabourey Sidibe

The Best Blacktresses: 2000s — In 2002, Berry became the first, and still only, Black woman to win the Best Actress Oscar, but what, if anything, did it do for her career?

Everett Collection - Design: Alex Sandoval

Gaborey Sidibe and Halle BerryThe Best Blacktresses is a weekly, seven-part series dedicated to the 13 Black women and their 14 performances (shout-out to two-time nominee Viola Davis) nominated for Best Actress in a Leading Role in the Academy Awards’ nearly 100-year history.

“This moment is so much bigger than me,” Halle Berry uttered in her disbelief, still struggling to gain her composure. “This moment is for Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne, Diahann Carroll. It's for the women that stand beside me, Jada Pinkett, Angela Bassett, Vivica A. Fox. And it's for every nameless, faceless woman of color that now has a chance because this door tonight has been opened. Thank you. I'm so honored. I'm so honored. And I thank the Academy for choosing me to be the vessel for which His blessing might flow.”

Berry earned every ounce of emotion she poured into her Oscars acceptance speech in 2002. Her win was monumental, some 50 years in the making, since Dandridge broke the Best Actress color barrier in 1955. The seventh Black woman nominated for the prize, Berry remains the only Black woman to have ever won it, two decades later.

Berry was born Aug. 14, 1966 in the same hospital as Dandridge, who had died a little less than a year earlier of an accidental overdose. She made the rounds on the beauty pageant circuit, winning Miss Teen All-American in 1985 and coming in second at the Miss USA pageant a year later. She transitioned from pageants to modeling to acting with her first project, the short-lived TV series Living Dolls, a spinoff of Who’s the Boss?, in 1989. Berry replaced Vivica A. Fox who had starred in the show’s backdoor pilot.

Though not classically trained like her contemporary — and last week’s Blacktress spotlight — Bassett, Berry was ambitious and hardworking, steadily building a career in a variety of roles. She made her film debut in Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever as Samuel L. Jackson’s crack addict girlfriend, and she had a breakout role as Eddie Murphy’s love interest in the 1992 rom-com Boomerang, also starring three generations of Blacktresses: Robin Givens, Eartha Kitt, and Grace Jones.

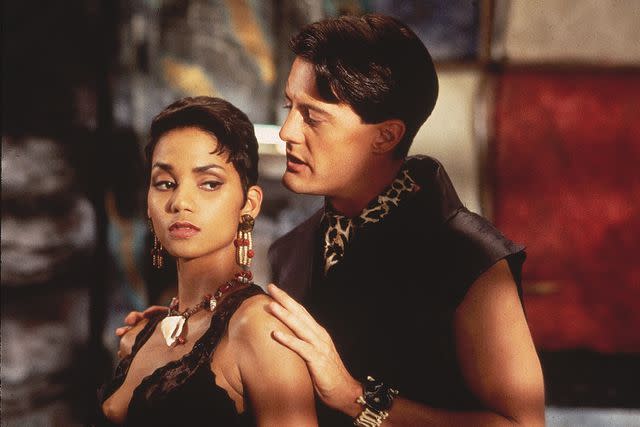

Ron Batzdorff/Universal

Halle Berry and Kyle MacLachlan in 'The Flintstones'She then tried her hand at historical miniseries with the Emmy-nominated Alex Haley’s Queen in 1993. The following year she landed her highest profile role yet as Miss Sharon Stone in The Flintstones, a role originally written for the actual Stone, who couldn’t do it because of scheduling conflicts. She starred opposite Jessica Lange in the 1995 melodrama Losing Isaiah and dipped her toe in the Hollywood action blockbuster pool with Executive Decision, but critical acclaim remained elusive.

Berry’s best role during this period was in the 1997 comedy B.A.P.S. Even though it was a critical and commercial bomb, Berry’s great in it. She shows a real commitment to comedy and it’s the most alive she had been on screen since her debut. In ‘98, Berry garnered the strongest reviews of her career to that point in Warren Beatty’s political satire Bulworth, though it failed to make much an impression at the box office.

New Line Cinema/courtesy Everett Collection

Natalie Desselle (center), Halle Berry in 'BAPs'After costarring in the Frankie Lymon biopic Why Do Fools Fall in Love with Fox, Lela Rochon, and Larenz Tate, Berry changed her image as an actress with the HBO TV movie Introducing Dorothy Dandridge. Berry had long dreamed of telling Dandridge’s story on film and worked tirelessly to get the project off the ground, serving as an executive producer. At the time, Whitney Houston and her production company were also trying to do their own Dorothy Dandridge movie, but Berry and HBO beat them to it.

Written by a then-unknown Shonda Rhimes, Introducing Dorothy Dandridge, rather serendipitously, brought Berry the kind of fame denied to Dandridge. She snatched up every Best Actress trophy for the role, including the Emmy, Golden Globe, and Screen Actors Guild Award, propelling Berry, a decade after her career started, into the league of “Serious Actress.”

Courtesy: Everett Collection

Halle Berry in 'Introducing Dorothy Dandridge'Monster’s Ball starred Berry as Leticia, a single mother with an obese son she abuses, whose husband was recently executed; Billy Bob Thornton as Hank, a corrections officer responsible for Leticia's husband's execution; and Heath Ledger, in his first role of consequence, as Hank's sensitive son, Sonny. The plot is a lot, full of needless tragedy, including the deaths of both Leticia and Hank’s sons. But it’s their enormous shared grief that bonds Hank and Leticia, culminating in a night of drunken sex as catharsis.

Bassett had turned down the role of Leticia in Monster’s Ball, feeling it perpetuated stereotypes about Black women. Vanessa Williams also turned down the part, but for very different reasons.

"I just had a baby, and I was like, 'I am not getting naked in front of a crew of people at this time!'" Williams said in 2014. "I saw [Berry] win the Academy Award, I was happy for her, but given a different set of circumstances, I might have done that role.”

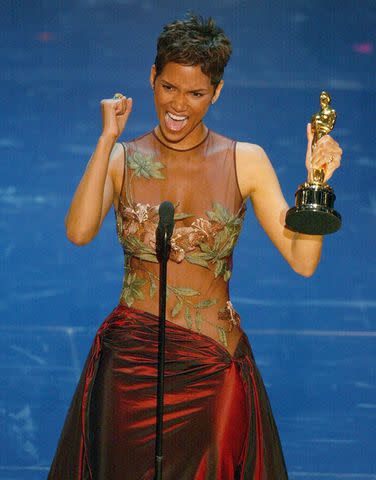

Berry earned rave reviews for the part, winning accolades left and right on the way to the 2002 Academy Awards, where she was up against Judi Dench in Iris, Nicole Kidman in Moulin Rouge, Sissy Spacek in In the Bedroom, and Renée Zellweger in Bridget Jones’ Diary. Honestly, great crowd. But Berry emerged triumphant.

Black people emerged triumphant. Not only did Berry win, but Denzel Washington took home Best Actor for his epic “King Kong ain’t got s--- on me” turn in Training Day, the first and only time African Americans won the two top acting prizes in the same year. Also that night, Will Smith was up for his first Best Actor Oscar for Ali, and Sidney Poitier, the first African-American to win a lead acting Oscar, received his Academy Honorary Award. The Oscars had never been so Black. And as if a form of self-correction, it never was again.

TIMOTHY A. CLARY/AFP via Getty Images

Halle Berry winning the Best Actress in a Leading Role OscarBerry’s role in Monster’s Ball might have been criticized, at least by Bassett, for perpetuating Black stereotypes, but those are often the kinds of roles that get Black people Oscars. And yet it’s not so much perpetuating stereotypes as it is harping on the tragedy and trauma and eventual triumph of Blackness. Black suffering wins Oscars. Operatic suffering. Which isn’t to say it isn’t true. And the Oscars also tend to equate great acting with great pain, which is why so few comedic performances win gold.

In 2009, Precious: Based on the Novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire generated a ton of buzz out of Sundance and Cannes. Directed by Lee Daniels (a producer on Monster’s Ball) and starring an unknown Gabourey Sidibe, comedian Mo’Nique, and diva extraordinaire Mariah Carey, the film took cinematic Black suffering to a whole other level.

Claireece Precious Jones is an illiterate, obese 16-year-old routinely abused by her unemployed mother, she’s been raped by her father resulting in two pregnancies, and later in her diagnosis with HIV. Precious finds salvation with the help of a caring teacher and a sympathetic social worker and is able to turn her life around and escape her mother’s cruelty.

Though maudlin, the movie doesn’t descend into trauma porn but instead benefits from flashes of Daniels’ bombastic style (he’s still one of America’s most interesting directors, even if it doesn’t always come together) and wonderful performances from Sidibe, Carey, and particularly Mo’Nique.

Mostly known for the sitcom The Parkers, Mo’Nique delivers a performance for the ages, and for her efforts she walked away with the Best Supporting Actress Oscar at the 2010 Academy Awards. Sidibe was up for Best Actress against Helen Mirren in The Last Station, Carey Mulligan in An Education, Meryl Streep in Julie & Julia, and eventual winner Sandra Bullock in The Blind Side, proving that the only thing the Academy loves more than Black suffering is white saviorhood.

Kevin Mazur/WireImage)

Gabourey Sidibe at the 2010 OscarsSidibe’s Oscar nomination for her film debut certainly gave her a form of legitimacy as an actress and an entry point, as a dark-skinned, plus-size actress, into Hollywood. She’s worked steadily since Precious, though never reaching the heights of her debut, which is also the problem with the Oscars. For most, getting nominated or winning is a career peak, one that most actors will never reach. But everything you do afterwards is in the shadow of that Oscar.

Berry’s post-Oscar career has been decidedly anticlimactic. She became the first Black Bond girl, stealing Die Another Day right from under Pierce Brosnan, but she was wasted in the X-Men series (and tricked into appearing in the third installment), and then there’s Catwoman. The 2004 high camp classic that hit that sweet spot of being so bad it was amazing. Just a swing and a huge miss, but what a swing.

Sharon Stone (the actress, not Berry's Flintstones character) played a villain with unbreakable diamond skin, and Berry as a non-canonical Catwoman with no connection to the Batman universe, painted into one of the worst costumes ever committed to celluloid. It was a spectacular failure, and it was all middling fare from there on out: Gothika, Perfect Stranger, Frankie and Alice, Cloud Atlas. Nothing if not resilient, Berry has kept plugging away, making her directorial debut with 2020’s Bruised, while popping up in popular franchise films like John Wick 3 and Kingsman: Golden Circle.

Still, it’s baffling just how overwhelmingly mediocre Halle Berry’s film career has been in the past two decades. An Oscar should afford some prestige, adding one’s name to a shortlist of leading ladies who can carry a movie or are capable of dramatic heft. It should be a golden ticket to the A list. Because she was the first Black woman to win the award, perhaps expectations were high — too high — for Berry’s trajectory, at least for Black audiences.

Everett Collection

Halle Berry in 'Catwoman'"I think it's largely because there was no place for someone like me," Berry reflected in 2020. "I thought, ‘Oh, all these great scripts are going to come my way; these great directors are going to be banging on my door.' It didn't happen. It actually got a little harder. They call it the Oscar curse. You're expected to turn in award-worthy performances."

Berry was among the actresses in the ‘90s whose work contributed to more complex portrayals of Black women on film. And her Oscar win presaged the moment in which we are living now, when there are myriad rich, diverse, dynamic roles for Black women — on television. And occasionally on film.

Black people are crafting the kinds of onscreen depictions of themselves that they want to see and they often side-step Hollywood film studios to do so. Streaming has been the great equalizer, reflecting an easy diversity that movies often struggle to manufacture. The movies can either get onboard or get left behind.

“It’s one of my biggest heartbreaks,” Berry said of her Oscar win. “The morning after, I thought, ‘Wow, I was chosen to open a door.’ And then, to have no one … I question, ‘Was that an important moment, or was it just an important moment for me?’ I wanted to believe it was so much bigger than me. It felt so much bigger than me, mainly because I knew others should have been there before me and they weren’t.”

Since 2002, Black films have won Oscars, as have Black screenwriters, Black filmmakers have been nominated for Best Director, there have been a number of Black Supporting Actor and Actress winners, and a handful of Best Actor winners. In other words, Black film is taken seriously, more often than not. And Halle Berry winning that Oscar is a big part of that. It really did open a door because it showed that Black actresses can deliver the kinds of performances that win Oscars.

It’s just that her Oscar might have done more for other Black women than it ever did for her. Which is really what breaking barriers is all about, making it easier for everyone that comes after you. And it can sometimes be a thankless role.

Want more movie news? Sign up for Entertainment Weekly's free newsletter to get the latest trailers, celebrity interviews, film reviews, and more.

Related content:

Read the original article on Entertainment Weekly.