Helter skelter: The history of Charles Manson and rock 'n' roll

Charles Manson, one of the world’s most notorious killers, pined to be one of the world’s greatest rock stars. Manson, who died Sunday at age 83, may have been known to most people as a manipulative cult leader and a ruthless murderer, responsible for ordering the slaughter of eight people in 1969, including actress Sharon Tate and her unborn child. But his reign of terror exploited a specific, and powerful, movement in pop culture. He enticed the young, largely female followers who made up his cult by twisting the language of ’60s hippies and by recasting the native excitement of rock ‘n’ roll for his own purposes.

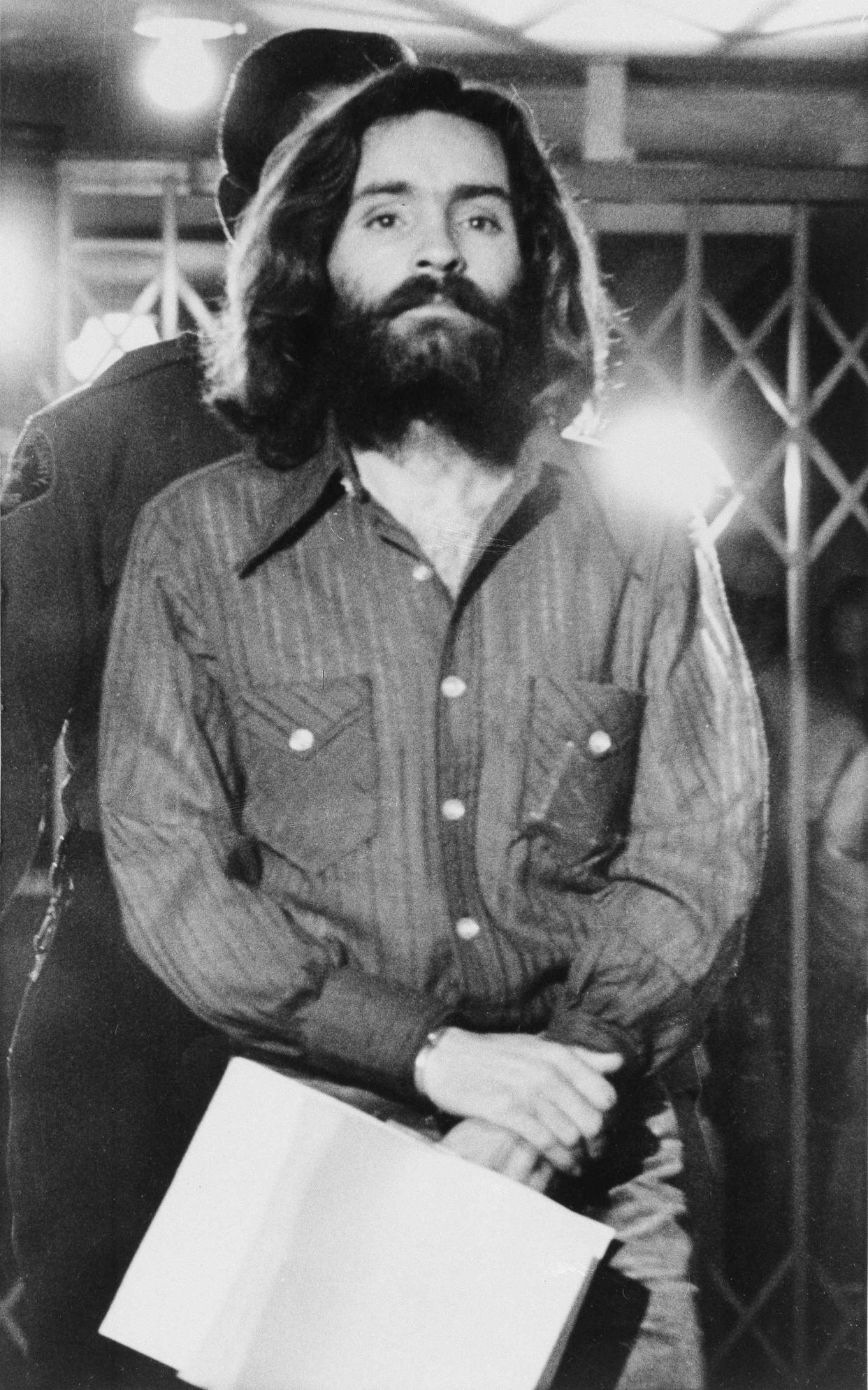

When Manson formed his gang, dubbed “The Family,” he was an aspiring musician, drawn to the counterculture’s ability to entrance the world’s young. He was older than the early 20-somethings who made up most of the cult; at the time, he was already in his late 30s. A career criminal who had spent most of his life in and out of jail, Manson used his time as a free man in the late ‘60s to pursue a career as a singer-songwriter. His ambitions came at a fortuitous time — the height of L.A.’s folk-rock trend, a sound that his crude songs and passable singing voice could potentially co-opt. Manson even had the right look: With his long hair and chiseled cheeks, he bore a striking resemblance Marty Balin of Jefferson Airplane.

Manson gained an important connection to the music world when, by chance, he met Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys. Wilson was initially drawn to Manson’s charisma, as well as to his bevy of comely female followers. Wilson even let some cult members live at his house for a while. Through that connection, the Beach Boys came to record a song based on a piece Manson had written, “Cease to Exist.” Crucially, Wilson changed the music, edited the lyrics, and switched the title to the far more positive “Never Learn Not to Love.” When the song appeared as a B-side to the single “Bluebirds Over the Mountain” in 1968, Wilson took full writing credit. Offended by the changes, and by his omission as the song’s inspirer, Manson threatened to murder Wilson, and even showed up at his house to make good on that vow. Yet by then the Beach Boy had relocated, spooked by the increasingly unhinged behavior of the Family members.

In August 1969, six months after “Never Learn Not to Love” appeared on the Beach Boys’ album 20/20, Manson initiated the first night of his killing spree. Tellingly, he ordered his gang to slaughter whoever was in a house in the Hollywood Hills owned by a man who had rejected his demos, producer Terry Melcher. (The producer was known for his work with the Byrds, Glen Campbell, the Mamas & the Papas, and others.) Melcher had rented the house to film director Roman Polanski, who was then off in Europe on a movie project. Polanski’s wife, Sharon Tate, the baby she was carrying, and three of her friends were there that terrible night, along with a houseboy. For months before their slaughter, Manson had hyped his followers with a doomsday scenario he named “Helter Skelter,” after a manic and disruptive cut on the Beatles’ White Album. By Manson’s insane reasoning, the Tate murders would incite a race war (dubbed “Helter Skelter”) in which black people would win out over whites. During that war, Manson’s entirely Caucasian gang would hang out in the California desert until the coast was clear. They would then swoop in and instruct the black race, whom he presumed to be inept, on how to run the world.

Manson instructed his killers to “leave something witchy” at the murder scenes. They overperformed on those nights, scrawling “Helter Skelter” on the door of the Tate house, written in the actress’s blood (though misspelled as “Healter”), and using the blood of the victims the next night (Leno and Rosemary LaBianca) to write the name of another Beatles song, “Piggies” (elaborated as “political piggies”).

By early 1970, police had solved the grisly case, arresting Manson and members of his gang. That led to a trial every bit as garish, theatrical, and observed as the O.J. Simpson ordeal more than two decades later. In March 1970, with the Manson trial still on, an album of Manson’s music was released. Titled LIE, the album cover repurposed an iconic image of Manson assuming his most demonic pose, which had originally appeared on the cover of Life magazine. The album included Manson’s initial demo for “Cease to Exist.”

In June 1970, Rolling Stone fulfilled Manson’s dream of rock stardom by putting him on their cover, though affixed to the less-than-laudatory headline: “The Incredible Story of the Most Dangerous Man Alive.” Decades later, many would decry Rolling Stone’s similar decision to put young Boston bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev on their cover, in a pose that made him look like a cool rock star, yet Tsarnaev had none of the rock-star aspirations that Manson had openly expressed.

Manson’s music began to surface again in the ’90s as the ultimate symbol of antisocial perversity. At the height of their fame, Guns N’ Roses recorded a song from LIE titled “Look at Your Game, Girl,” which they included as an unlisted track on their 1993 album “The Spaghetti Incident?” Bartek Frykowski, son of Manson murder victim Voytek Frykowski, later received $62,000 for every million copies of the album sold from GNR’s label, Geffen Records. The royalties were the first money he had received since winning a $500,000 federal lawsuit against Manson in 1971.

A year after the GNR controversy, Marilyn Manson borrowed some lyrics from the Manson song “Mechanical Man” for his cut “My Monkey,” found on the Portrait of an American Family album. Marilyn, aka Brian Warner, had long ago taken his stage name from the murderer, fulfilling his mission to give everyone in his band the first names of superstars and the surnames of serial killers (“Twiggy Ramirez,” “Madonna Wayne Gacey,” etc.).

In 1992, Marilyn Manson’s Nothing Records labelmate, Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor, became the final resident of the original Manson murder location at 10050 Cielo Drive, renting the house and setting up a home recording studio dubbed “Pig”; the majority of NIN’s breakthrough album The Downward Spiral was recorded there. In a 1997 interview with Rolling Stone, Reznor expressed regret over that decision after meeting Sharon Tate’s sister. “She said: ‘Are you exploiting my sister’s death by living in her house?’ For the first time, the whole thing kind of slapped me in the face. … I guess it never really struck me before, but it did then,” Reznor recalled. “She lost her sister from a senseless, ignorant situation that I don’t want to support. When she was talking to me, I realized for the first time, ‘What if it was my sister?’ I thought, ‘F*** Charlie Manson.’ I don’t want to be looked at as a guy who supports serial-killer bulls***.”

Charles Manson’s music received more cultish exposure through a cover of his “Never Say Never to Always,” cut by actor Crispin Glover, and a take on his track “Garbage Dump” recorded by nihilist punk rocker GG Allin. Later, the Manson case inspired several band names, including Kasabian (named for one of the killers at the Tate house) and Spahn Ranch (dubbed for the Family’s desert hideout). Beyond rock ‘n’ roll, the cult inspired an opera, The Manson Family, by John Moran, and part of a Broadway musical, Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins. The latter features a character based on Manson acolyte Lynette “Squeaky” Fromme, who in the mid-‘70s attempted to kill President Gerald Ford.

Over the years, several other albums by Manson’s cult have appeared, including The Family Jams, corralling songs recorded by the group after Manson’s arrest, and One Mind, a collection of poetry and spoken-word pieces created years after the killings. Manson himself continues to have a hold over the public consciousness as the incarnation of the berserk con man, someone who exploited rock’s revolutionary stance to advance his own dystopian agenda. It’s an image, and a concept, horrific enough to stoke a fascination as powerful as it is perverse.