Inside ‘Pachinko’, The Apple TV+ Hit From Soo Hugh That Captured Hearts

The journey from page to screen for Pachinko began in 2017, on a plane ride from London to New York.

The transatlantic flight was a typical commute for Soo Hugh, who at the time served as executive producer and co-showrunner on the first season of AMC’s The Terror. Nearly seven hours in the air provided an opportunity for Hugh to finally—though somewhat hesitantly—dig into Min Jin Lee’s recently released New York Times bestseller. Theresa Kang-Lowe, Hugh’s former agent and friend, had sent it her way.

More from Deadline

“I felt very ambivalent about reading it just because I knew it was going to be very personal,” Hugh says. “I knew that it was going to be this beautiful story and I also was just finishing up another big international show, so I was in a very particular headspace at that time.”

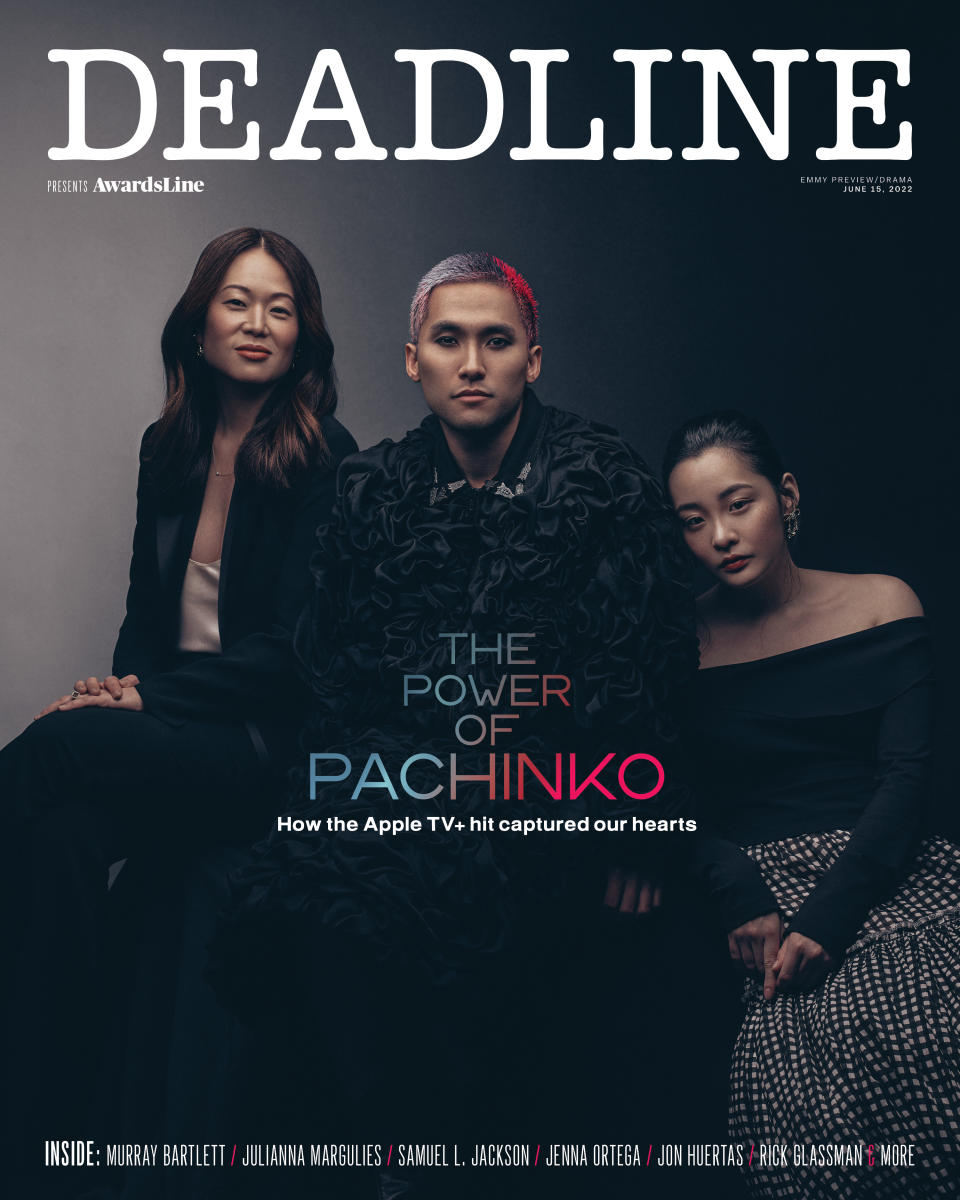

Josh Telles/Deadline

While fellow passengers scrolled through in-flight entertainment options and shifted in their seats to find optimal nap positions, Hugh immersed herself in the life of a young Korean woman in a rural fishing village on the coast of Busan, South Korea, during the era of Japanese colonial rule from 1910 to 1945. As she flipped from chapter to chapter, Hugh encountered Lee’s meticulously crafted words about protagonist Sunja’s boarding house duties, laundry routines and her secret love affair with a mysterious fish broker. From Lee’s specific descriptions of adolescence, maternity and Korean customs, Hugh says she connected “on an internal core level” to Sunja, despite her own vastly different experiences as a Maryland-raised Korean American television writer.

“I was really jolted by that shock of recognition. I wasn’t expecting it to be that visceral,” she recalls.

Several hours and scores of emotional pages later, a bowl of white rice brought Hugh to tears. In the book, Sunja’s mother Yangjin pleads to a merchant for a measly amount of white rice to celebrate her daughter’s sudden marriage. At the time, the Asian cuisine staple was incredibly scarce and reserved only for the Japanese and elites. A satisfying bowl of immaculate and steaming rice can certainly beget a powerful reaction. But in the matriarch’s desperation to provide anything and everything to her child, Hugh saw her mother, her grandmother, and all those who came before her.

But even despite that familiarity, Pachinko wasn’t a story Hugh felt she could adapt for television. At least not in its original structure. “I just didn’t see that show as one that I thought I could tell linearly, and so I was like, ‘I love the book, I’m going to put it away, I’m not the right person for it,’” she says.

Then came Hugh’s “eureka moment”, one that would remix Lee’s sprawling novel for the television format. Inspired by the time-skipping, country-hopping elements of The Godfather Part II, Hugh decided to follow not just one generation of the book’s central family, but two—putting Sunja’s coming of age in direct conversation with that of her grandson, Solomon. A non-linear approach presented a stage where Hugh could show how themes like home and identity—and the lack thereof—played out across past and present generations. How the choices of yesterday molded the privileges of today.

“What if this was a story about generations and specifically following generational trauma from one generation to the next, and creating a conversation about that?” Hugh asked herself. “Sunja’s life becomes the foundation, but upon that foundation you build this pretty amazing narrative structure.”

Confident with her newfound approach to Pachinko, Hugh, with Media Res’s Michael Ellenberg and Lindsey Springer and Kang-Lowe’s Blue Marble banner, began her search for a platform. With multiple buyers throwing their hats in the ring, Hugh knew she and her team had something special in the works. However, that spark in connection didn’t quite click until she sat down with Apple TV+ and Michelle Lee, the streamer’s director of domestic programming. It was “electricity in the air” when the two finally connected.

As Hugh recalls, the pitch meeting didn’t feel like one at all. What started off as Hugh’s attempt to convince Lee and her team to bring the trilingual immigrant story about a Korean family to TV, evolved into an emotional release for both sides. Perhaps it was that “shock of recognition” again.

“At one point very early on in the pitch I was watching [Lee] and I saw her tearing up, and then the minute I see her tear up I’m starting to lose it a little bit,” Hugh recalls. “That was a lot. I had to stop looking at her because my voice was shaking so much, and I just had to look at the spot on the wall behind her.”

She continues: “I just don’t think I’ll ever forget that pitch. It didn’t feel at all like I was trying to sell something at that moment. It felt like I was really having this very human connection with someone.”

From then on it was a done deal. By August 2018, the news broke that Apple would adapt the bestseller with Hugh at the helm. Less than a year later in March 2019, the streamer ordered the series. Author Lee was initially slated as an executive producer early in the process, but eventually dropped out of the project. She “just wasn’t creatively involved”, Hugh explains.

Nevertheless, Hugh marched forward with a distributor and a new vision on her side. She assembled her writers’ room, populated with some scribes who tapped into their own immigrant stories, and sought out the aid and talents of directors Kogonada (After Yang) and Justin Chon (Blue Bayou) to help bring her multi-generational conversation to life.

Then came the task of casting nearly 600 roles for Pachinko. Naturally, a series that concerned itself with multiple countries and numerous generations required a large enough lineup to fit time and space.

In a Yeongdo fish market, merchants and fishers display their freshest catches—eel, squid and abalone—while hollering their best prices. All the commotion comes to a sudden halt when two Japanese officials walk through the aisle, prompting nearly everyone to bow their heads in respect—except for one young woman who stands unfazed and unimpressed by their presence. This is the first time that audiences meet the teenage Sunja, and through her, fresh-faced newcomer Minha Kim. Wearing a stainless, traditional hanbok, Kim’s Sunja seems to float through the fish market, magnetizing the audience and her eventual love interest Koh Hansu alike.

Josh Telles/Deadline

Kim, whose credits included Korean indies and the series School 2017, graduated from the Hanyang University’s Department of Theater and Film in early 2020. She was supposed to move to New York to kick start her stage career in the U.S. and enrolled in courses at the New York Film Academy, but life and the pandemic had other plans. Still experiencing the aimlessness all too common among recent grads, the Korean actress said she was searching for a great story to take on. Luckily a casting director had just the thing for Kim, who had neither a manager nor an agent in her corner at the time.

“Pachinko is totally a gift for me,” Kim says.

After learning about the project, Kim sped through Lee’s book overnight and sent in her self-tape. Hugh was initially cynical when the casting director first claimed she found the perfect fit. She had heard that line before. But after a worldwide search with a number of “extraordinary actresses”, callbacks and conversations, it was clear to Hugh and her team that Kim had cracked the Sunja code.

“You just got sucked in. There was something, everything we wanted. Timeless and yet specific. Innocent yet wise. Real and authentic,” Hugh recalls of Kim’s audition tape. “It was there from the very beginning.”

Throughout the series, Kim stretches her abilities to embody the joyous highs and devastating lows of Sunja’s coming of age. She stands tall in her silent defiance against the Japanese in the fish market. She shrinks in heartache and tears when she reveals her accidental pregnancy to her on-screen mother Inji Jeong. While seemingly effortless in her portrayal of the series’ central matriarch, Kim’s work wasn’t without rigorous research.

Like the creatives behind Pachinko, Kim engaged with numerous historical resources to better comprehend the geopolitical and social conditions surrounding Sunja during the late 1920s. Books and documentaries on the subject supplemented her school knowledge. Kim also looked to novels written during the turbulent era to fill in the gaps of fact with humanity and emotion. Her most valuable resource, however, was one she had known since birth.

Kim grew up hearing her grandmother, who had remained in Korea throughout the Japanese occupation and World War II, speak about her own experiences. Her grandmother’s stories of survival often filled the silence at various family gatherings. But Pachinko offered a rare opportunity for Kim to dig even deeper into her own family’s history.

“We talked for a few days and every time I heard a story from her, I couldn’t stop crying,” Kim recalls. “It was an intense conversation, and I can feel the intimacy between my grandmother and me. It was so precious.”

Kim cross-examined the facts she came across in historical journals and documentaries with her inherited primary source. “‘Is that true? Did you really do that?’ And she said, ‘Obviously, it was worse than that.’” From Kim’s own time with her grandmother came a character in which viewers could identify their own mothers, family members and themselves.

Back in the Yeongdo fish market, K-drama heartthrob Lee Minho makes his debut as the respected, or feared, Koh Hansu, an older Korean businessman with his own traumas and connections to Japanese elites. Lee found himself doing something that he hadn’t done in nearly a decade: auditioning for a part. The audition process isn’t the most common practice in the Korean entertainment scene, and even less so for stars like the Boys Over Flowers breakout. But he was game.

“He’s like, ‘This is new for me, let’s try,’” Soo remembers of Lee’s audition. “Minho’s just one of those people that really thrives on challenges. He just likes always trying new things, so this was new for him. He’s like, ‘Interesting, let’s see how this process works.’”

A self-proclaimed “big fan” of the hit high school series Boys Over Flowers, Kim says she felt an immediate “great power” from her co-star during the chemistry audition.

“He has such powerful eyes. Whenever I look at his eyes, I get energy from his eyes,” Kim notes.

Apple

A longing gaze in the fish market is what sets off the series’ central romance and Sunja’s complicated multi-national journey. Kim views Lee’s Hansu as an encyclopedia of sorts for her character. After their initial encounter in the fish market, Sunja and Hansu grow close. He explains what the world has to offer outside of her small fishing village—abundant electricity, sweet oranges and candies.

On a riverbed boulder, Hansu roughly charts a map of the world for Sunja, including Japan and the United States, nations Sunja and her descendants will eventually attempt to call home as ‘Zainichi’—ethnic Koreans who migrated to Japan under colonial rule, and their descendants.

Several decades after the Japanese occupation of Korea and World War II, a 74-year-old Sunja flies first class from Osaka back to the Busan shores of her childhood. She runs from her taxi to the water. As she revels in the feeling of the sea’s welcoming, wet embraces, rain begins to pour. Droplets become indistinguishable from her tears of joy. This moment could not have been more frustrating for Oscar winner Yuh-jung Youn.

“I tried to put all the emotion over there, and then all of a sudden, they start pouring the rain,” Youn says. “I couldn’t act. I was upset with [director] Justin [Chon]. Sunset was just going down very fast, so I was just frustrated.”

Fresh off her Oscar-winning turn as the uncouth Grandmother Soonja in Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari, Youn says she felt an “immediate connection to Sunja”. Convincing the Korean acting vet, whose career spans more than 50 years and titles, including Dear My Friends and Lucky Chan-Sil, to take on another matriarch was no issue. Getting her to audition, however, was another story.

According to Hugh, Youn “rightfully so” rejected the request to try out. Youn, an icon in her own right, said auditioning for the Pachinko role held a certain weight for her career.

“I told [Hugh and Kogonada], ‘I understand your culture, but in Korea, everybody knows me. If I fail, they will think I failed, even if I’m not suitable for that role,’” Youn explains. “If I audition for that role, and then if I fail, rumor will get all over the country. ‘Oh, Yuh-jung Youn failed that role.’ I didn’t want to have that reputation. I didn’t want to ruin my 50-year career with one audition.”

What followed were conversations between Hugh, Kogonada and the star. Youn, born in North Korea shortly after the Japanese occupation, spoke about her personal connections with the character. She said her mother, like Sunja, lived through the Korean War, Japanese occupation and World War II. Born in 1947, Youn said she also experienced some of Korea’s turbulent history herself. She knew that she could play this role better than anybody. After conversations with the actress, that also became evident to Hugh and Kogonada, who directed four episodes including the pilot.

While her mother’s experiences of perseverance did not precisely match those of Sunja’s, Youn says her family history informed and nourished her performance as the Baek family matriarch: “It’s all in my body and in my thoughts.” The same goes for her own experiences as a single mother to two boys. While she didn’t have to sell kimchi in a foreign land to make a living like Sunja, Youn took up any opportunity to provide for her children following her divorce.

“I’d just get any job, any role. Maybe if they asked me to audition at the time, of course, I would do the audition,” she laughs.

In Pachinko, Sunja’s sacrifice and need to provide extends well into the ’80s to her grandson Solomon, portrayed by Love Life and Devs alum Jin Ha. A prestigious university graduate with a well-paying and seemingly stable career, Solomon can easily represent what many immigrants hope for in their future generations. The unspoken pressure to succeed after multiple eras of sacrifice, however, only grows more complex with his family’s geographical displacement and historical discrimination. Throughout the series, Solomon attempts to persuade a reluctant Zainichi Korean landowner to sell the only home she’s known since the colonial era to impress his boss in Japan, who himself questions where the young financier’s internal loyalties lie.

Josh Telles/Deadline

“He’s already juggling so many different sides of himself,” says Ha, who is Korean American. “Whether it’s interacting with his Zainichi family in Osaka—what that means in terms of straddling the two cultures and histories there within himself—or if it’s him existing in spaces in Tokyo as a Zainichi person, and then, on top of that is his experience in America as an Asian American. The specifics of his Zainichi identity… it’s not a welcome or understood nuance. It reproduces itself into something else that’s not found in Japan or Korea.”

Some of the series’ most obvious departures from the original novel lay within Solomon. Using the character’s 50 pages as a starting point, Ha worked closely with Hugh to further flesh out his character’s various arcs, from his professional pursuits to his final moments with ex-girlfriend Hana. As Hugh says, “Solomon is our clay… let’s take that scalpel, and we’re going to form a human being.” Ha recalls that Solomon posed a peculiar challenge for Hugh, perhaps because he “demanded a sort of self-reflection that maybe she didn’t have to go through with a lot of the other characters”.

“We were working on this character together like we were two actors working on the same role. The conversations felt that easy and that personal too,” Ha says. “It was a lot of the traumas in our own life or the experiences in our life that resonate with Solomon’s character and therefore we can try to understand where he’s coming from.”

From expressing the complexities of Solomon’s identity to building some of his story from scratch, Ha says that he felt his Pachinko character was “certainly the biggest and most challenging role” of his career yet. To make the character even more of a challenge, Ha had to speak in three languages: Korean, English and Japanese. He was fluent in the first two coming into the role but received assistance from a team of translators and dialect coaches for the latter, once cast.

Pachinko presents audiences with color-coded subtitles—yellow for Korean dialogue and blue for Japanese. Each character interaction, across nations and eras, presents a unique set of subtitle combinations. Heart-wrenching dialogue between a teenage Sunja and her mother is entirely yellow. Solomon’s promises to boss Abe-san flash blue. But conversations between Solomon and his father Mozasu (Soji Arai) can often display both, to indicate switching between the two languages.

For Hugh, featuring all three languages—each with various dialects and accents—was essential.

“[Without the languages] I think you have no idea what it means to lose your home and then go to a country that’s not yours,” she says. “I think you have no idea what it means to speak from one generation to another and not be able to speak fully with them just because your language isn’t there. All of our big themes would have fallen completely flat.”

Engaging performances by devoted actors and linguistic authenticity are just two parts to the equation behind Pachinko. A massive, transnational saga also required transporting audiences through history and across country lines. The season’s eight episodes take viewers from from a humble boarding house in Yeongdo, to the dimly-lit and grimy streets of Ikaino, Osaka; to the site of the devastating Great Kantō earthquake and to the geometric finance offices where Solomon seeks to prove his worth.

Production, which began in October 2020, brought Pachinko’s cast and crew to Korea and Vancouver. The series was supposed to also film in Japan, but pandemic restrictions put a wrench in the initial plans. Nevertheless, production designer Mara LePere-Schloop and her team worked to place and recreate the scaffolds and silhouettes of the past.

Like the stars’ performances themselves, building out the world of Pachinko required deep research into various eras of architecture, geography and more. The designers, with teams based in Korea, Japan and the U.S., consulted a variety of resources including rare photographs to build their historically accurate visions. The result are environments that help the performers, like Kim, immerse themselves into their respective decades.

“I couldn’t shut my mouth. I was just taking photos of [the sets] secretly,” Kim says. “Mara and [prop master] Ellen [Freund], I would always tell them ‘Thank you so much for making these fascinating sets. It helps me so much.’”

Set against a meticulously constructed recreation of an Osaka train station, is one of the most significant scenes in both the book and series. Sunja, now a mother of two sons, maneuvers a wood cart stocked with kimchi. Onlookers, both Korean and Japanese, sneer at her fermented cabbages, fearful that the dish’s trademark smell will drive away business. Now the primary breadwinner following her husband’s arrest, Sunja taps into the business savvy and persuasion of her hometown fisherman to convince passersby to sample, and purchase, her kimchi.

“Best kimchi in the world! My mother’s special recipe,” she touts. “This is my country’s food!”

One of the final frames of the season, the kimchi scene—with a standout performance by Kim, decade-defining sets from LePere-Schloop and even era-appropriate cabbage sizes curated by Freund—is a definite culmination of the many layers of intentionality and dedication from across the Pachinko team.

While a series that seeks to dazzle with star power, size and scale, at its core Pachinko is a tribute to a community whose stories haven’t had much time in the spotlight. With its season finale, Pachinko brings the fictional tale back to its roots by featuring the testimonies of real-life Sunjas: Zainichi Korean elders. Filmed in Japan during the pandemic, the intimate conversations see the women—who range from 85 to 100 years old—reminisce on loss, hunger, and the challenges of assimilation. But while flipping through scrapbooks filled with black-and-white family photos, the women also reflect on the lives they’ve made for their families, despite the history that they’ve come to accept, not resent.

The testimonies were initially slated to come at the end of what Hugh imagined as a four-season journey. But unsure whether Pachinko would even make it to Season 2, Hugh says she “started to feel this sense of urgency. Who knows how much longer these women will be with us?”

She continues: “[Pachinko] was built on the backs of real people who lived. These lives really did have this kind of trajectory and we really wanted to make that as powerful as possible. These women, for so long they didn’t think their stories were at all worthy to be told, and the lives of all those women are anything but boring. They’re extraordinary.”

Confronting the past—by having intimate conversations with our elders, flipping through history books or embodying those who came before us—is what molds identity and keeps the often private, personal stories of survival and love from slipping between the cracks of the monumental.

Exposing the experiences like those of her mother to educate younger generations like her sons’, was Youn’s mission for Sunja. “You need to learn the history, and why we are who we are today,” she insists.

Sunja’s story may be one among millions of migrants, but it’s one that hits home for viewers across ethnicity, nationality and age. The evidence? The viewers who have sent Kim Sunja-themed gifts and expressed that they felt seen in her performances.

“Whenever I got their reactions, I feel like I’m alive,” she recalls of one fan event held at an Apple Store in Korea. “This is my responsibility as an actress and as a storyteller. This is my job. I feel so proud of my job. Whenever I get people telling me that, ‘You remind me of my grandmother,’ I’m speechless because even though I’m not Sunja in real life, I get the chance to give them courage, which I get a lot of courage from other actors and actresses. It’s like the vice versa. It’s so mutual.”

Facing similar interactions was Ha, who recently had a ride-share driver tell how Pachinko has educated her on the Zainichi experience and Korea’s history. With moments like that, Ha says, he “couldn’t ask for anything more in my heart”. Pachinko has clearly created conversations about family and helped renew interest in Korea’s past, but even just on paper, the series is a welcome and sophisticated addition to the ever-growing American television landscape. As Hugh notes, a show like Pachinko—with its predominantly Asian cast told in three languages centering on a minority of the Asian diaspora—would not have been possible even five years ago. But in 2022, Pachinko is a reality and is nothing short of “groundbreaking”, notes Ha.

“We live in a world of superlatives and hyperbole, but I think ‘groundbreaking’ is actually accurate. There have been other American-produced shows that have featured multiple languages, but I don’t think at this scale and certainly not these languages. How much it centers, and focuses almost entirely on, Korean and Japanese and Zainichi characters… I don’t think we’ve seen that before, especially from our own perspective. It’s about us. It’s for us.”

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Solve the daily Crossword