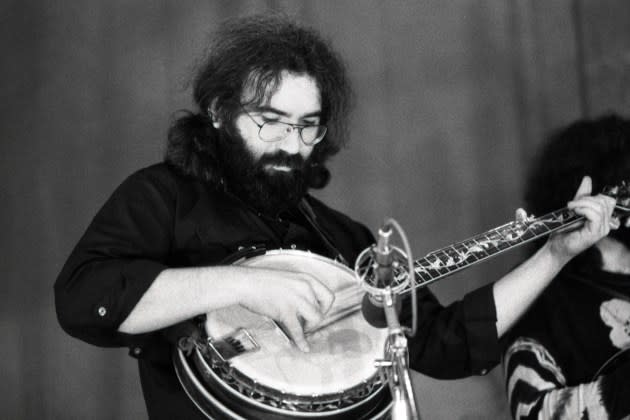

Jerry Garcia: What It Was Like to Play Bluegrass with the Grateful Dead Guitarist

In 1973, Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia fulfilled a longtime dream when he formed the bluegrass supergroup known as Old & In the Way. For the rock & roller, circling back to his acoustic roots was more than just scratching a creative itch — it was a spiritual calling.

“It was something that was organic and fun,” Peter Rowan, singer, songwriter, and former OITW guitarist, tells Rolling Stone. “And that evolved into playing [shows]. ‘Let’s take this outside.’”

On the ground level, Old & In the Way’s self-titled 1975 debut album was one of the biggest selling bluegrass records of all time, until the juggernaut O Brother, Where Art Thou? soundtrack edged it out in 2000. But to dig below the surface of Old & In the Way is to find both a landmark album and a juncture of virtuoso musicians who forever changed the course of bluegrass.

More from Rolling Stone

“I think what makes it so special is that it was like this shooting star,” Rowan says of the band. “If you were lucky enough to see it, you saw it. If not, you heard about it.”

In celebration of the innovative group, and to specifically honor an often-overlooked chapter of Garcia’s storied musical journey, the Bluegrass Hall of Fame in Owensboro, Kentucky, will unveil the special exhibit “Jerry Garcia: A Bluegrass Journey” on Thursday.

The elaborate showcase is expected to run at the museum for the next two years, and its unveiling is set to feature panel discussions with bluegrass greats like Rowan, Ronnie McCoury, Pete Wernick, and Drew Emmitt. There will also be live performances from Leftover Salmon, David Nelson, Jim Lauderdale, Kyle Tuttle, and more.

To preface, before Garcia formed the Grateful Dead, he originally hailed from the bluegrass, folk, and roots music realms of the late 1950s and early 1960s — thick musical threads that remained at the foundation of the Dead throughout its tenure. Alongside his lifelong friend and songwriter partner, Robert Hunter, the duo were fixtures in the San Francisco music/art scene of the burgeoning 1960s counterculture.

“A lot of people forget [Jerry] and Robert Hunter were huge bluegrass guys before the Dead became ‘the Dead,’” Rowan says.

Playing acoustic guitar and banjo, Garcia took a deep dive into all avenues of acoustic music, especially bluegrass. It’s been widely said that one of Garcia’s tightly held aspirations as a young musician was to one day become a member of Bill Monroe’s band, the Blue Grass Boys.

As the “Father of Bluegrass,” Monroe represented the big bang of the genre, with Garcia even traveling east to Pennsylvania in the early 1960s to possibly audition for Monroe. The location was Sunset Park in rural Chester County. With a setting of Amish buggies, horses, and folks sitting on wooden benches taking in Monroe’s music, Garcia had second thoughts.

“I think [Jerry] took a look at the scene and realized if he did get the job, this would be his life,” Rowan says. “Everything was just starting in California. Jerry couldn’t envision himself in a coat, tie, and cowboy hat working with Bill Monroe.”

Rowan himself worked for Monroe. In 1964, he was hired as the lead singer and rhythm guitarist for the Blue Grass Boys. By 1967, Rowan left Monroe and started collaborating with mandolinist David Grisman.

What resulted from that Rowan/Grisman partnership was the short-lived group Earth Opera — a blend of the duo’s love of bluegrass and jazz music, as well as the mind-expanding nature and sonic possibilities conjured by marijuana and LSD.

By October 1972, Rowan moved to the West Coast. He again was hanging and jamming with Grisman in San Francisco, specifically the Stinson Beach area. They formed another group, Muleskinner, a bluegrass project that lasted only a brief period of time and featured standup bassist John Kahn and fiddler Richard Greene, the latter also one of Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys.

“We all believed in [bluegrass] as a music that was not limited to just countrified folks and rural audiences,” Rowan says. “It’s very uplifting. It’s got gospel tunes, transcendent songs of spiritual longing, unrequited love from a tradition of old ballads.”

Also in that moment, Grisman introduced Rowan to Garcia and the trio came together at Garcia’s one day to play with no expectations — simply to enjoy each other’s company, instruments in hand.

“[David] mentioned that Garcia lived up the hill and liked to play bluegrass,” Rowan recalls. “So, David and I went up there [to jam]. We’d go to Jerry’s every night.”

Unbeknownst to all present that fateful day, a musical fire was sparked that continues to burn bright and remain vastly influential to generation after generation of bluegrass players and listeners.

“After a few hours of picking, [Jerry] turned to us and said, ‘We’re old and in the way,’” Rowan says on a famed OITW recording.

Garcia mentioned to Rowan and Grisman that he’d like to book some gigs as OITW and the band had been birthed. “I got to play bluegrass guitar with a guy who was just infinitely loving music,” Rowan says of his time with Garcia.

With Garcia on banjo, Rowan playing guitar, and Grisman taking up mandolin duties, the ensemble also featured Kahn on bass. Greene, John Hartford, and Vassar Clements rotated on fiddle. With the rising popularity of the Dead in the 1970s and the increasingly manic fandom aimed at Garcia from the counterculture and beyond, the OITW shows became sold-out “you had to be there” concerts.

“Jerry was the draw,” Rowan recalls. “And there were Deadheads going, ‘What is this? Fiddles, banjos, mandolins, and acoustic guitars?’”

For its debut album, OITW released a live recording from its Oct. 8, 1973, appearance at the Boarding House in San Francisco. The set list included traditional melodies (“Pig in a Pen,” Knockin’ on Your Door”), recently penned Rowan tunes (“Midnight Moonlight,” “Panama Red,” “Land of the Navajo”) and even a Rolling Stones number (“Wild Horses”).

“Bill Monroe had a vision that his music was much more appealing than just to a rural audience — Old & In the Way was the catalyst to prove that point,” Rowan says.

More and more dates were booked, but OITW only ended up lasting the better part of two years. By 1974, OITW faded away, mainly due to Garcia’s obligations with the Dead and the soon-to-be formed Jerry Garcia Band, both of which were filling up his schedule. So, too, were the obligations of the rest of OITW in their own artistic endeavors.

“Sometimes things are special because there was a limit to them,” Rowan says. “Those days in your late twenties, you’re just ambitious for all kind of different things, you know?”

Garcia died in 1995, Kahn in 1996, Hartford in 2001, and Clements in 2005. Although Greene is still alive, his touring days are long over. Subsequent OITW live recordings have seen the light of day over the decades, but nothing much beyond that.

In 2002, a reunion album, Old & In the Gray, was released, featuring Rowan, Grisman, and Clements. As of today, only Rowan and Grisman are still touring and performing certain melodies from the OITW repertoire.

To note, a special OITW tribute show will take place on June 30 at the Caverns in Pelham, Tennessee. Rowan will be onstage, as will Grisman’s son’s band, the Sam Grisman Project.

“It’s fun to have something that is still recognizable after 50 years,” Rowan says. “That’s a gift in the music world.”

Best of Rolling Stone

Solve the daily Crossword