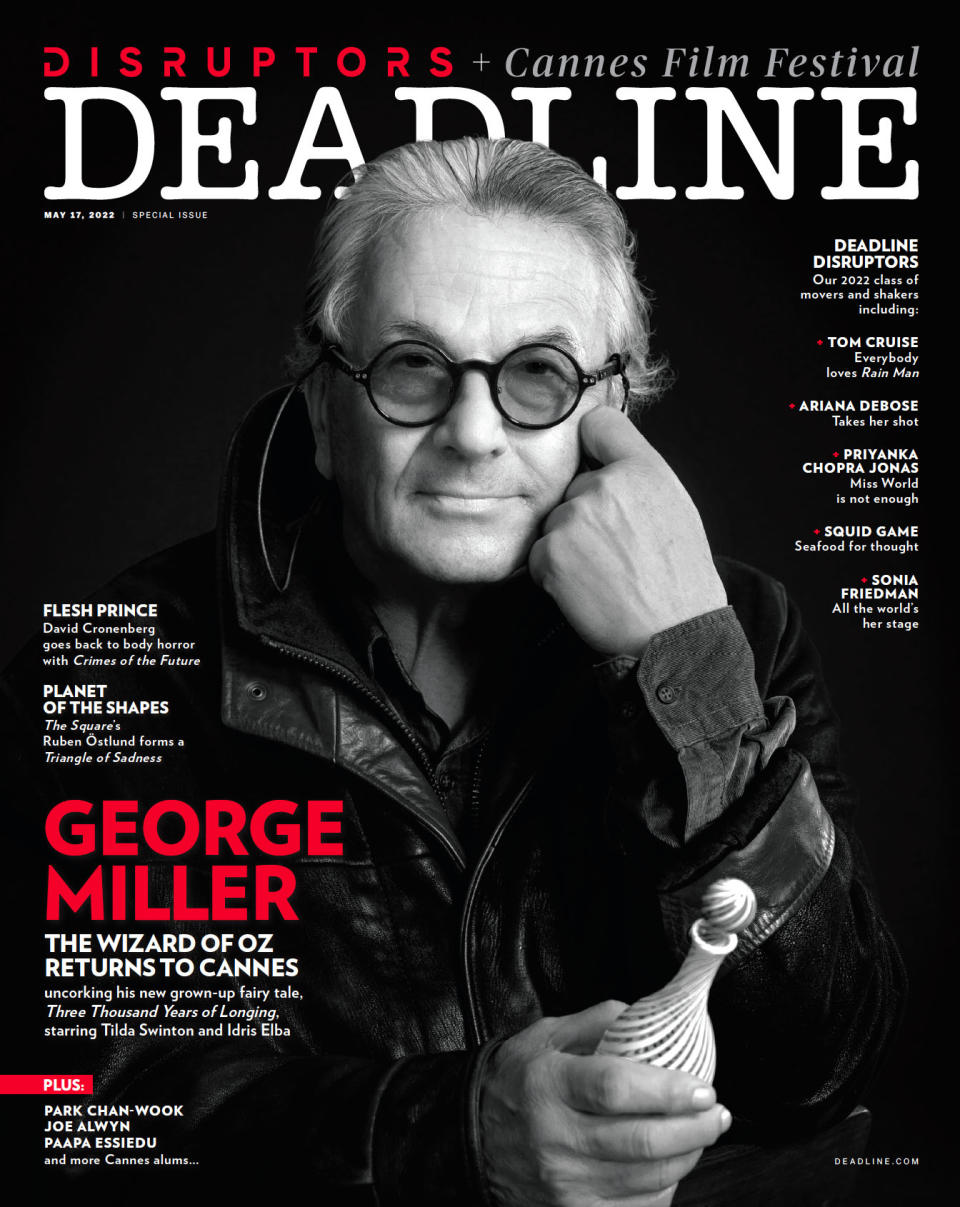

London West End’s Queen of Drama Sonia Friedman Is Conquering All The World’s Stages — Deadline Disruptors

When she was 23, Sonia Friedman was—to use her expression—thrown into a rehearsal room with Harold Pinter at London’s National Theatre. She was his deputy stage manager during production for the premiere of his one-act play Mountain Language starring theatrical royalty Michael Gambon and Eileen Atkins.

More from Deadline

NEON Picks Up Domestic To Horror Pic 'Enys Men' Ahead Of Directors' Fortnight Premiere - Cannes

Rotterdam Announces New Programming Team In Cannes Amid Festival Revamp

“I was the person sitting right next to [Pinter],” she recalls. “He would whisper into my ear all the way through,” about how he wanted it to look, where’d there’d be a cue. She says the playwright would make almost no changes to his script. “Though he did at one point add a pause and asked me to write that into the script,” she says, smiling at the memory. It was a life-changing moment for her, working with playwrights who directed their own work. “I fell in love at that point, particularly with new work, watching actors mine something that no one else in the world has ever seen before.”

She wanted more of that experience. Until then, she hadn’t really known what she’d wanted to do, let alone what a producer did. Something in the arts, sure. But what?

She’d given up the cello when she was a teen because, she says, she realized she’d never be as good a classical musician as her estranged father, the classical violinist Leonard Friedman, whose storied career included co-founding the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and the Scottish Baroque Ensemble. Nor would she ever be as skilled as her brother Richard Friedman (‘Ricky’ to her), a leading violinist, and one leader of the London Symphony Orchestra. Or her sister, the theater artist, singer and director, Maria Friedman. Her mother, the concert pianist Clair Friedman, would play for hours and hours.

Friedman was 12. “I found it too difficult having a violinist father and brother who were so brilliant, and I couldn’t cope with not being as brilliant as they were,” she says. “I also know my personality and character type is such that unless I could do it terribly well, I’d never be satisfied.” She might also have become an opera singer. But there was little encouragement for her to get the necessary training.

Paul Coltas

Pinter whispering in her ear, though, sparked a career that has, in the intervening 34 years, seen her emerge as one of the world’s top theatrical producers, working with a stellar array of talent including Gillian Anderson, Benedict Cumberbatch, Lily James, Mark Rylance, Imelda Staunton and many more. She has worked with writers like Tom Stoppard and Robert Ike and directors like Stephen Daldry, Ian Rickson, and Ivo van Hove. Her list of collaborators is almost endless.

Deadline first broke the news that Friedman would soon reteam with Van Hove to produce a stage version of Stephen King’s The Shining, set to feature Ben Stiller. “It’s half confirmed,” is all she will allow. She’s so nervous discussing it out loud that she crosses her fingers.

If it happens, though, the show, which she’s producing with Colin Callender, will get its start on the London stage sometime in 2023. She stresses that Van Hove will adapt King’s book and not Stanley Kubrick’s 1980 movie.

Simon Annand

Friedman has 25 productions up and running in the U.K., the U.S., Germany, Japan, Australia and points in between. Three stages on London theatreland’s fabled Shaftesbury Avenue boast her productions. A revival of Jez Butterworth’s masterwork, Jerusalem, is at the Apollo with Mark Rylance revisiting the role he originated 12 years ago. Next door at the Gielgud, Aaron Sorkin’s adaptation of Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, directed by Bartlett Sher, opened to rave reviews with Rafe Spall as Atticus Finch. Further along Shaftesbury Avenue, the Palace Theatre is home to Harry Potter and the Cursed Child.

A fourth show, which resides across Leicester Square, is her production of The Book of Mormon, at the Prince of Wales, a house owned by Cameron Mackintosh. During the pandemic she, along with Mackintosh and Michael Harrison, a producer of glittering pantomimes and musicals like The Drifters Girl, engaged on a daily basis, supporting each other professionally and, from a distance, emotionally.

It was from the Palace’s wings that Friedman would watch her sister, Maria, perform in a 1980 production of Oklahoma! The show was a revelation to the girl who’d been steeped in Bach and Vivaldi. No surprise then that she’s one of the producers the transfer to the Young Vic of Daniel Fish’s electrifying, reimagined version of the Rodgers and Hammerstein musical, that played at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn back in 2018, before moving to Broadway.

Undoubtedly, theater is Freidman’s first love, though in recent years she has been an executive producer on television productions, partnering with Callender on The Dresser, led by Anthony Hopkins and Ian McKellen; and on Richard Eyre’s TV film of King Lear with Hopkins, Emma Thompson, Florence Pugh, Jim Carter, Emily Watson, Jim Broadbent and Tobias Menzies. She is also a co-producer on Callender’s six-part television adaption of Hilary Mantel’s acclaimed Wolf Hall, directed by Peter Kosminsky and starring Mark Rylance.

A production of Uncle Vanya directed by Ian Rickson, starring Toby Jones and Richard Armitage, was enjoying a good run at the Harold Pinter Theatre before it was forced to close due to the pandemic. She and collaborators sprang into action and filmed it for a cinema release. It also enjoyed a season on the small screen.

Two recent TV productions, Together, directed by Stephen Daldry and Justin Martin and starring James McAvoy and Sharon Horgan, and short film People You May Know with Arthur Darvill and Lydia West, were both BAFTA-nominated. (Together won the BAFTA for best single drama).

Friedman confirms that she’s open to the idea of establishing a television and film department within Sonia Friedman Productions. There’s hesitancy, not simply because it’s a mammoth undertaking, but because she believes — is “absolutely convinced” even — that the digital world must always be secondary to her theater operations.

At the height of Covid, she says, there was endless debate about whether digital would be central to their work. “Will it supplant it? It can’t,” she responds adamantly. “I’d get out of the industry.”

She is determined that if she did enter the space, she would create a separate division to “either develop, from the ground up, work for television, or to be inspired by the [theater] work we’re doing and seeing if those stories could perhaps be adapted in a different way for TV.”

Johan Persson

She insists that it won’t be a division “that’s going to take the work and do an NT Live,” referring to the National Theatre’s livestreamed broadcasts of theater productions. “I’m not going to do that.”

One property is being set to test the waters. The Shark Is Broken is a biting stage comedy-drama about an aspect of the making of Steven Spielberg’s 1975 movie, Jaws. It’s co-written (with Joseph Nixon) and co-starring Ian Shaw, son of the film’s Robert Shaw. Shaw portrayed his own father when the play transferred from Edinburgh to the Ambassadors Theatre last Autumn.

A three-hander, The Shark is Broken is a gripping study of how Jaws actors Richard Dreyfuss, Roy Schneider and Shaw coped with being cooped up on a creaky boat for endless hours during the making of what has become a classic blockbuster.

The Shark is Broken is headed for a future life in North America and New York in the coming months. “The Jaws fans are legion and absolutely adore it,” Friedman says. “We’re simultaneously exploring a life for the story in some form on film.”

Is Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem a contender for the screen? Unlikely, she says, then adds cautiously, “But you never know.”

Friedman’s U.S. adventures include a Broadway-bound production of Tom Stoppard’s mournful play Leopoldstadt — a study in heartbreak that was playing at Wyndham’s Theatre in London when theaters and places of entertainment closed due to the pandemic. She’s in second position as a producer of August Wilson’s The Piano Lesson, directed by LaTanya Richardson and starring Samuel L. Jackson, who is Richardson’s husband, as well as Danielle Brooks and John David Washington. The revival is due to open this October.

Friedman was asked by The Piano Lesson’s lead producer, Brian Moreland, and Wilson’s estate if she would join the production.

Does that mean she’ll transfer it to London? “I hope so,” she beams. “The reason I was asked to join was because of the U.K. I’m hoping very much that we can bring it over with that cast.” She’s excited about Richardson directing. “How wonderful that LaTanya’s getting her Broadway debut as director. She talks about this play as if it’s been in her DNA forever.”

She is equally excited that Denzel Washington is producing a film version of The Piano Lesson, which she won’t be participating in. However, they have conversed. “An inspiring man,” she says.

Hadn’t Scott Rudin been involved at one point with The Piano Lesson? Rudin famously withdrew from his own productions when he faced a public backlash over allegations of bullying his staff. He and Friedman partnered on many shows on both Broadway and the West End.

“I haven’t had any contact with him,” says Friedman, later noting that it’s been “a year” since they last spoke. “When I worked with him, well, you know what Scott’s like, he was completely inspiring and very exacting, and I enjoyed our collaborations. And in many respects I learnt a huge amount from him,” she says.

Manuel Harlan

How has the relationship unraveled from a business stance? With Book of Mormon, she says that her point of contact was always with Anne Garefino. “Nothing has changed on Mormon. We run it here [in London], nothing has changed there. Their business relationship (Garefino and Rudin’s) has changed, but not mine.”

Similarly, with To Kill a Mockingbird. “I’m Barry Diller’s partner and Barry has his own set up with Scott. I don’t know what it is, and I don’t need to know. I have no direct relationship with Scott.”

It’s vital to revisit Friedman’s childhood to understand how she has survived, and prospered professionally, in the shark-infested waters of the entertainment business.

She says that her father abandoned his family, “before I was even born. He went pretty much during my mum’s pregnancy.”

Her mother was left to attempt to raise four children under 10. “Our father was a huge spirit; very charismatic, a very great musician who couldn’t cope with the children. He’d had terrible advice from his mentors who said, ‘You’ve got to choose between art and family.’ He chose his art,” she says.

Their way of surviving such a catastrophic loss in the family was to tell stories. Her brother Ricky would get her out of bed and take her downstairs to the piano room where he’d play the piano then spend hours playing make-believe, “putting on shows, all made up from our imagination.” Maria, and Sarah, her older sister, would join in, too.

“We all have our life stories, and I wouldn’t have chosen another one,” she says. But she was often angry and confused. “I was a 10- or 11-year-old who would pretend to people at school — when I went to school that is — that my dad had died, because of the shame of having a dad who never saw me or knew me. The best I could get out of him was a telegram on my birthday, which was always a day late because my mum would have told him to send me one.”

Once her siblings had left home, she was mostly alone because her mother was often away touring, though a friend of her mother’s would pop in to check that she was eating. There was little concern over her schooling. She’d often bunk off and spend time on her own in a laundry closet she’d stocked with dolls. “I was very lonely and a bit lost, but I had my stories,” she says.

Her brother had encouraged her to think of stories that would surprise and give the tales ridiculous titles and start from there. “One of them was The Swiss Fridge Mender,” she recalls.

These experiences shaped her philosophies on work. She’s very happy, she says, if audiences want easy. “But I don’t want easy,” she insists. “If it’s something visceral I get a chill. If I’m not hooked on something I’m reading by the first 20 pages, boom, gone. Fine, other people can do it. There are many plays that go on that I’ve rejected because they didn’t make me go, ‘Oh, f*ck!’ Or because I knew what was going to happen next.”

It’s great to have those instincts, she says, but also irritating, “because I can go to a film and I know what’s going to happen next. That’s because of my family. My brother, particularly, told me to always look around the corner, in all stories.”

I have a four-page list of her productions, past and present. I realize that although she wrote none of them, a few are strangely semi-autobiographical, in the choosing of them, at least.

Take Matthew Lopez’s The Inheritance, inspired by E.M. Forster’s Howards End, and directed by Stephen Daldry. Her interest in that sprang from her activism in the 1980s and 1990s during the AIDS crisis. Friedman was a volunteer ‘buddy’, often joining forces with the actor Kelly Hunter, and later joined by producer Caro Newling, to mount mammoth fund-raising drives for causes concerning AIDS.

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child was incredibly personal to her, as well. Friedman was interested in Harry as an orphan, and how his son Albus would cope with having a famous dad. “I also wanted to understand: What does it do to a child whose parent had no parenting? How can they parent?” That was her way in when she and Callender met with J.K. Rowling. “And it chimed with Jo,” she says. “Just exploring the inner life, the inner turmoil of a child told at 11 they’re a wizard. I tapped into something that I thought was yet to be explored, and that obviously I couldn’t have done without my life experience.”

The events of Friedman’s childhood, thought by many to be failures, had strengthened her and that strength was demonstrated in the career that she subsequently built. It’s what has made her such a disruptive force in the theatrical world. But Friedman’s modesty makes her shy from the word. “Disrupt almost feels like a choice or a decision, and it’s not,” she says.

Rather, it’s about doing the work she believes in, she says, “on my terms and not on any sort of textbook rules. And sometimes, therefore, it won’t happen because you don’t necessarily get the backing. But if disrupt means not following a formula; if disrupt means never trying to emulate last year’s success; if disrupt means always striving to give audiences what they think they don’t think they want; then fine, I’m a Disruptor.”

She ensures that writers, actors, directors, designers and other creatives “feel safe, supported, nurtured. It’s no bad thing earning some money in the commercial world from the thing you do. But it’s about support.”

She adds, “The most important moment for any producer is the moment you put together your creative team. You know what your play is, or your musical, or whatever it is. It’s not my job to then interfere. It’s not my job to intervene. It’s not my job to tell them what I want to see, because they’re the artists. I want them to do what I believe is going to really surprise me. I never, ever want to be the smartest person in the room.”

What if there’s something she’s not liking? “Of course, I will do what I can to encourage, support to take it in a slightly different direction, to note it, but it will aways come from a place of love. It will always come from a place of belief, fundamentally, in what they’re trying to achieve as opposed to my vision up there. It’s got to be their vision.”

I see Friedman again following a preview of Jerusalem. Forced to close her shows during the pandemic, Mark Rylance had called to ask what he could do. “We can do Jerusalem,” she replied.

So it was that a month into the pandemic, Friedman announced that the play was coming back to the West End. The play is a four-letter word — or a finger — to authority, and it still lands, perhaps even more than it did when it first played. Rylance’s performance as the incorrigible, iconoclastic Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron seems deeper. The audience is clearly stirred by Butterworth’s play. Friedman agrees that it’s more devastating, heartbreaking.

“It’s about his needing to be free,” she says. “Thank God there’s a piece of work out there that’s allowing us to think and feel.”

I mention the imaginary ghosts that Rooster conjures up and say that we’re at a point where we need giants. “To save us”, Friedman said, finishing my sentence. “I have to believe those giants are going to come.”

Stephen Sondheim’s Giants In the Sky from Into the Woods comes to mind. Softly, quietly, Friedman begins to sing. “There are giants in the sky, there are big, tall terrible giants in the sky…” It’s one of her favorite musicals.

Several days after that private performance, Friedman sends a text from New York, where’s she’s overseeing the opening of Funny Girl, a production that began five years ago out of the Menier Chocolate Factory Theatre located on the south side of London Bridge.

“I think I could sing you a Sondheim for every occasion in my emotional life — happiness, joy, pain, anger, love and of course loss. He understood what it is to be alive. What a ginormous loss. But what a legacy,” she writes.

She’s not fussed about her own legacy. She’d stop tomorrow if the stories dried up. But that’s not likely. Robert Icke’s production of Oedipus had been set up pre-pandemic with Helen Mirren and Mark Strong. Both Mirren and Friedman confirmed that Mirren is no longer available to play Jocasta, because of a scheduling clash. Another artist will be cast. Strong is still connected to the project, which is not dated.

Icke’s also directing The Doctor, his acclaimed adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s Professor Bernhardi. It played at the Almeida Theatre in north London three years ago and will now transfer to the Duke of York’s Theatre starting Sept. 22 with star Juliet Stevenson.

Casting continues, Friedman says, on Merrily We Roll Along, starring Daniel Radcliffe. Her sister, Maria will be directing later next season at the off-Broadway New York Theatre Workshop. The play is based on a production that she directed at the Menier Chocolate Factory.

Isn’t Sonia Friedman one of those giants come to save us?

Could be.

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.