The most offensive film ever made? Why Jerry Lewis buried The Day the Clown Cried

Not many unreleased films have the honour of a new documentary about them premiering at this year’s Venice Film Festival and are about to become the potential basis of a high-profile remake. Although “remake” might not be quite the right word, given that the original was never completed to any satisfactory degree.

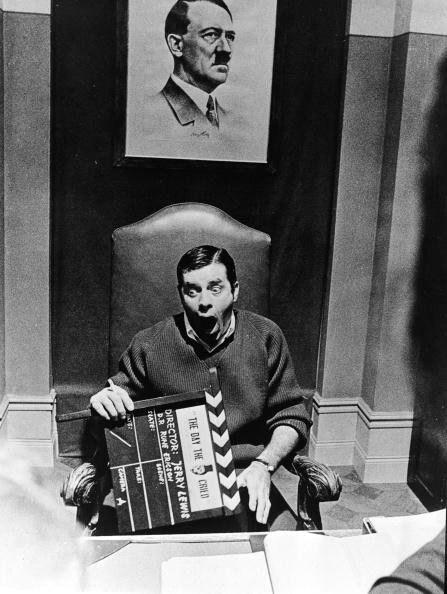

This may be just as well. Jerry Lewis’s ill-fated 1972 Holocaust-themed comedy The Day The Clown Cried has long since become a byword for horrendous tastelessness and misplaced schmaltz – and it would be a brave man or woman who attempted to salvage anything from the wreckage.

K Jam Media founder Kia Jam may be that brave man. He has made his money and reputation producing such pictures as the all-star noir thriller Lucky Number Slevin and the Sin City sequel A Dame To Kill For, but his “reimagining” of Lewis’s picture would be on an entirely different artistic level. According to Jam, he was introduced to the original script written by Joan O’Brien and Charles Denton courtesy of a rabbi who had an office on the same floor of the building as him. Lewis had rewritten their script extensively, in an attempt to deviate from his patented blend of wild and crazy humour to achieve the critical recognition that he had always craved as a serious artist, rather than merely a clown.

Jam, however, believes that the original screenplay has misunderstood greatness in it. As he told Deadline, “The first 20 or so pages are a little clunky and felt very dated. Then, I got into the story, I was so taken by the script. When it was done, I was sobbing. I ended up just going home. I couldn’t really do anything for the rest of the day.”

As originally written, The Day the Clown Cried focuses on an over-the-hill circus clown, Helmut Doork, who had a successful career in the pre-war era in Germany and Europe but has been worn down by the rise of fascism and his own fading comic skills. When Doork gets drunk in a bar and abuses Hitler, he is arrested and thrown inside a concentration camp as a political prisoner, never to be put on trial but kept there as a reminder to his peers of the perils of disrespecting the Führer. Yet Doork finds himself offering a mixture of hope and escapism to the inhabitants of the camp, not least the children, who he seeks to entertain in the face of the horrors around them. At last, disgusted by the horrors of the fascist regime, he sacrifices himself by leading his charges into the gas chamber, attempting to comfort them to the last.

It could have been terrific. But Lewis proved to be completely the wrong man to bring it to the screen. According to his biographer Shawn Levy, the comedian was desperate to return to relevance with a meaningful project that would demonstrate his versatility. “There was certainly a part of him that wanted to tell the story, but a bigger part, I believe, was hoping for a chance to establish for audiences, critics, and maybe even himself that he was a genuine artistic talent and not just a comedy performer on the decline,” Levy says. “But his career was already in a significant downward spiral.”

Lewis was bitter. “He never had a remotely positive reputation as an artist among American critics as a filmmaker – unfairly, in many cases,” Levy continues. “And his popularity had waned significantly by the time he turned to making this film. He was deeply thin skinned, and it really angered him that he wasn’t taken seriously.”

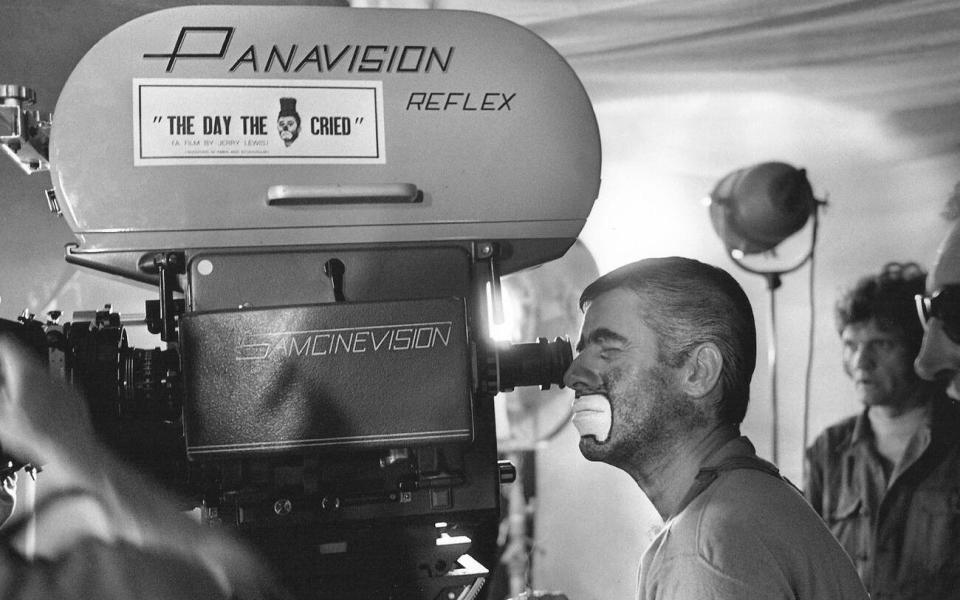

Lewis embarked on the project hoping that it would win him Oscars, and such was his keenness to create a work of lasting greatness that he also directed it. After undertaking a tour of Auschwitz and Dachau for inspiration and losing 35 pounds by only eating grapefruit for six weeks, he headed to Sweden in April 1972 to begin filming. Yet despite these preparations, Lewis was a hopeless director – and, tragically, he seemed to know it. He drank heavily on set in Sweden, losing whatever meagre grasp he had on the picture.

His problems were compounded by the fact that the producer Nat Wachsberger – a Belgian impresario behind such undistinguished films as the heist thriller They Came To Rob Las Vegas and Orson Welles’s The Southern Star – had allowed his option on the script to lapse before production even began. Lewis, therefore, had literally no right to film the material. So when the money ran out, the Swedish studio seized the working print and all the additional footage meaning that it could never be legally released, though Lewis retained a copy of everything he had shot.

Still, this may have been a blessing. Few people have ever seen the picture – which supposedly only exists in fragmentary, rough form – and the comedian Harry Shearer is one of them. He was horrified. “The closest I can come to describing the effect is if you flew down to Tijuana and suddenly saw a black velvet painting of Auschwitz,” he reported. “Seeing this film was really awe-inspiring, in that you are rarely in the presence of the perfect object. This movie is so drastically wrong, its pathos and its comedy are so wildly misplaced, that you could not, in your fantasy of what it might be like, improve on what it really is.”

Levy himself – who once elicited such a violent response from Lewis when he asked him about the film that he was shaken for weeks – said that “It would have been excruciating to sit through, I’m confident, but not necessarily in the ways that Nazi-themed films of the era such as The Night Porter and Salo were.”

Jam, then, is faced with an uphill struggle, not only in tackling such uncompromising and difficult material, but in expunging memories of what Lewis himself described as “either better than Citizen Kane, or the worst piece of s___ anyone ever loaded on the projector”. Yet the producer is unbowed by the challenge. With the mysterious rabbi’s help, he has acquired the rights to the original screenplay, a process that he estimates has taken him three or four years “and a small fortune in legal fees”. However, he believes it all to be worth it in order to film “by far the most powerful script I’ve ever read”, which Lewis produced a confused and compromised version of. (Jam, like most of the world, has not seen the original picture, and claims to have no desire to do so.)

The success of Jonathan Glazer’s uncompromising and oblique Holocaust picture The Zone of Interest has meant that there is certainly an opportunity for a talented and fearless director to place their stamp on this material. Jam claims, “I had it financed once or twice over the years, but was unable to bring on the calibre of filmmaker that this needs. You really need a master craftsman to tell his story. The actors that sign on to be in this movie are going to want to know they’re in very good, capable hands. I was unable to do that.”

There have been occasional rumours about a remake before – once with Robin Williams, who ended up filming the softer, vaguely similar-themed Jakob the Liar instead – but until now, nothing concrete has materialised, perhaps in part because Roberto Benigni’s once-beloved, now-reviled Life Is Beautiful covered similar territory, to Oscar-winning effect.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there in terms of the original movie and what Jerry did and didn’t do,” Jam admits. More clarity may come after the Venice premiere of the From Darkness to Light, the behind-the-scenes documentary. According to its publicity, it promises to offer: “extensive never-before-seen production footage and behind-the-scenes impressions from the original ‘lost masterpiece’ itself.” Most intriguingly, the directors suggest that “new light has been shed on the darkness of what really happened”.

Will the mystery of The Day the Clown Cried finally be solved? Perhaps we’ll know in a few weeks time. Meanwhile, many had expected – “hoped” seems too strong – that 2024 would see the film become publicly available for the first time. Before his death, Lewis donated his personal copy of his print to the Library of Congress in 2014 with the stipulation that it was only to be seen after a decade.

However, it has subsequently become clear that the archive does not possess a finished copy of the picture, merely a series of rough cuts of scenes with unsynced sound reels. Fascinating for film scholars and Lewis completists, perhaps – as well as the masochistically inclined – but deeply frustrating for the rest of us.

If Jam’s grand ambition comes to pass, then this holy grail of notoriety will have a second and hopefully more rewarding life. His belief that the second coming of The Day The Clown Cried will be a deeply and vitally important picture is certainly commendable. Even if it is too late for Lewis to have the last laugh.

NB. This is an updated version of a piece first published in August 22