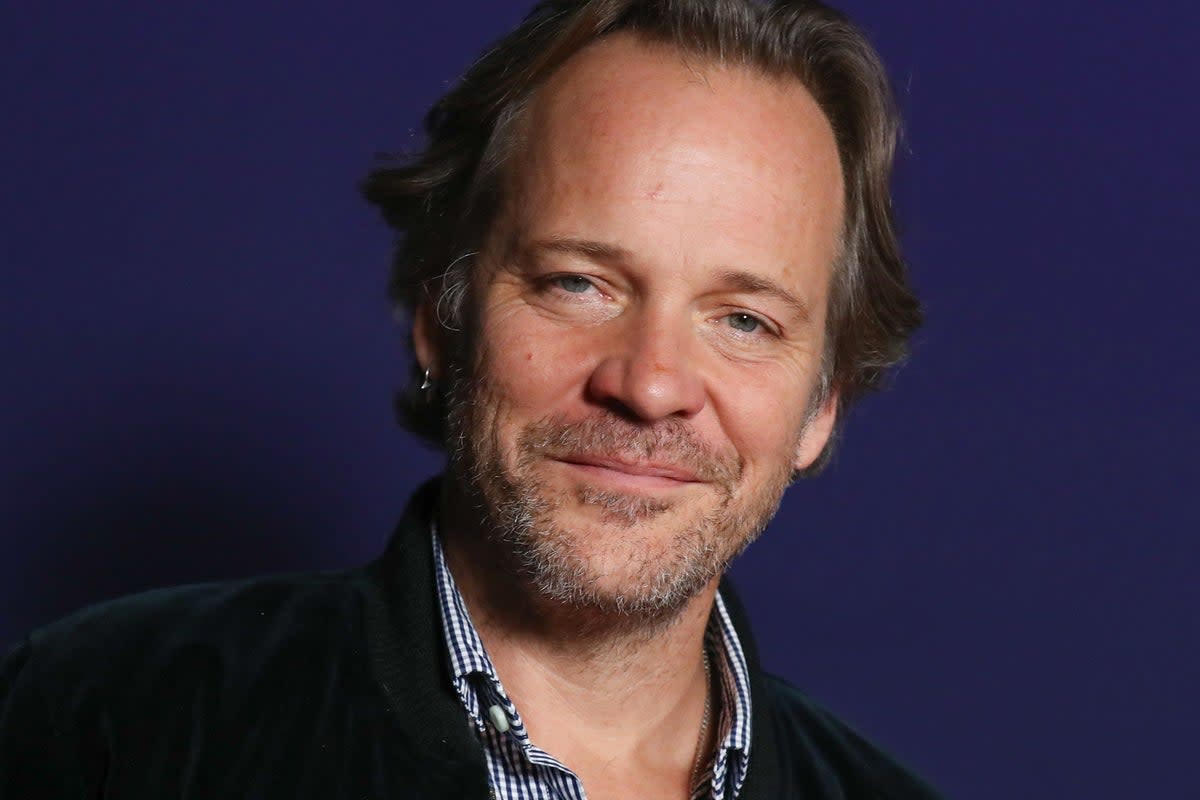

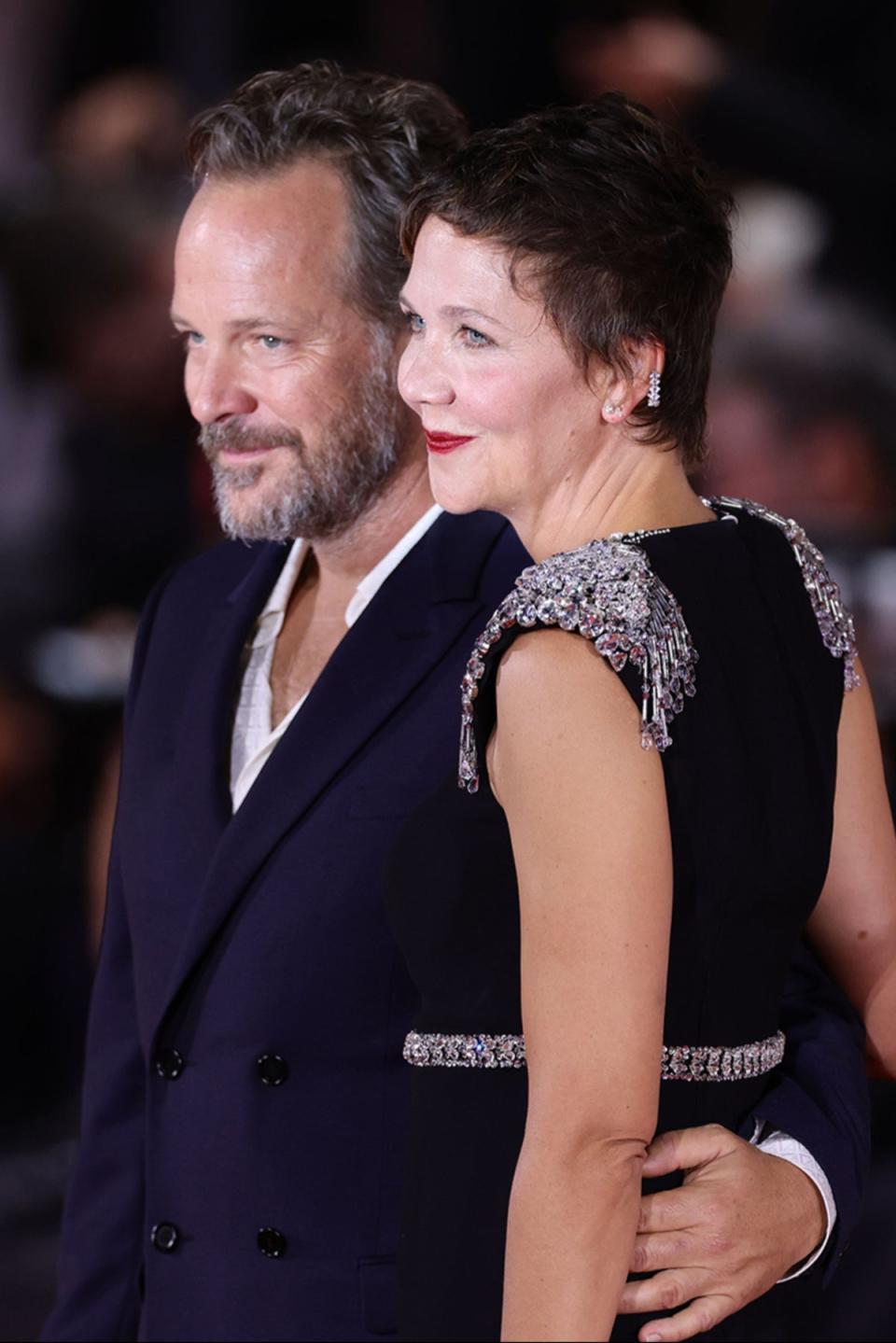

Peter Sarsgaard on nudity, insecurity and marriage to Maggie Gyllenhaal: ‘I’m not critical of how I look in films – it’s more in life’

Trim and boyish-looking, the Emmy and Golden Globe-nominated actor Peter Sarsgaard has never had a problem with scenes involving sex, nudity or the busting of taboos. In the biopic Kinsey, he bared all and seduced Liam Neeson. In the psychological thriller The Dying Gaul, he was masturbated by Campbell Scott. For director Maggie Gyllenhaal – his real-life wife – he humped a tree in the short film Penelope and slept with one of his students in The Lost Daughter. “I’m such an object of desire in that movie,” he tells me from the study of his brownstone home in New York. “I couldn’t be more the object of desire!”

There’s full-frontal nudity in his new film, too. Memory tells the story of Sylvia, a traumatised rape victim (played by a clenched and gloriously un-glossy Jessica Chastain), who falls for Saul, a man with young-onset dementia. Sarsgaard is magnificent in the role, which won him the Volpi Cup for best actor at last year’s Venice Film Festival. And Memory, as a whole, is a triumph, one of the most edgy and uplifting films of the year. Here’s what’s surprising: though Sarsgaard is happy to strip, he’s insecure about his appearance. “I don’t love the way I look,” the 52-year-old tells me. “That’s true of many people. But I guess it’s unusual, since I’m an actor.”

He points out that he’s fine watching Memory, even though he says he’s “heavier” in it than he’s ever been, a result of an injury that left him unable to exercise for a few months before filming. “I have all those disclaimers with this character, [so] I don’t mind the way I look in it.” He adds that it’s harder for him when he’s playing a role in which a well-kept appearance is particularly important. “You know, where you’re supposed to look like Hugh Grant. Then all that stuff – the fretting – comes in. But luckily I don’t play a lot of characters like that. I don’t get that critical of how I look in films.” He sighs. “It’s more in life.”

Not that he’s given to self-pity. Sarsgaard’s wife has been vocal about the way women in Hollywood are constantly judged on their appearance, especially as they approach middle age. He totally takes her point. Suddenly animated, he says, “I’m so thankful to be a man!” He explains how he and Gyllenhaal recently bumped into an actor in her fifties. “I was standing there, just listening to Maggie and this woman talking about how difficult it is to be an actress getting older. That kind of thing is always eye-opening. As I’ve gotten older, the parts I’m offered have got more interesting. As a man, I take so much for granted.”

He’s delighted Gyllenhaal has found a way to be visible within the film industry. “I’m extremely proud of what my wife has done, which is to completely reinvent herself. Though, to anyone who knows her, it’s not actually a surprise.”

Gyllenhaal’s second feature, The Bride, is a big Warner Bros-backed studio movie that riffs on James Whale’s 1935 horror classic Bride of Frankenstein. Also scripted by Gyllenhaal, it boasts an incredible cast that includes Jessie Buckley, Christian Bale, Penelope Cruz and Annette Bening. Sarsgaard plays the detective trailing Frankenstein’s monster (Bale), his recently-created mate (Buckley) and maybe someone else. There are rumours Buckley’s “bride” will couple up with Cruz’s character. But Sarsgaard won’t give anything away. All he’ll say: “It’s this big, romantic, deeply romantic, wild, punk monster movie! I think it’s going to be energising! It’s rambunctious! People are going to be very surprised that this is Maggie’s second movie. It is nothing, at all, like The Lost Daughter.”

I have a need to know what’s going on with people around me. It might be irritating to live with me, actually, because I’m always spying in one way or another

Gyllenhaal has paid tribute to Sarsgaard in the press, saying that while she filmed The Lost Daughter he took care of “the family side of things”, a rare example of a man “gracefully, intelligently” supporting his partner. Do people tell his wife she’s lucky to have him? He looks incredulous. “I feel like I’m the one who’s lucky. Lucky to have Maggie! Because now I have my own director who’s gonna put me in her movies. I always wanted to work with someone over and over, making that relationship deeper and more interesting. I don’t think I’ve ever worked with the same director more than once. My wife is the only one!” So is that the plan? He’ll become the Gena Rowlands to her John Cassavetes? “That sounds good! That sounds really good! Though I don’t know if The Bride is what you’d call a Cassavetes movie.”

When they’re at home, Sarsgaard and Gyllenhaal don’t discuss work. “We’re shooting The Bride at the start of April,” he says. “I know Maggie’s talking to some of the other actors in the movie, but she and I have almost said nothing. She just knows that’s not my way of working. I read a script a lot. Then I daydream about all the things that aren’t in it.”

He’s the kind of actor who thinks a script always has room for improvement. When Sarsgaard reads one and sees a phrase like “he cries”, he’ll usually cross it out. “I’ll decide if I find something moving. You don’t get to tell me. You could do that with anyone. I’ll come up with something else!” He elaborates on a theory he’s clearly given thought to. “What someone writes on a piece of paper, in their apartment, has nothing to do, really, with what we do on the day… It’s very hard for a writer to fully invest in each character and give them their own point of view. That’s why you hire actors.”

Surely some filmmakers disagree? “Almost never,” he says, with a sly smile. “Because I come to the set with a positive attitude. I don’t verbalise anything. When they call action, I just start doing it my way. Then I listen to what the directors say, and try to incorporate it, or if it doesn’t make sense to me, I start working with them.” He’s sure directors enjoy collaborating with him. “Michel Franco, who directed Memory, said the Spanish word for ‘script’ is ‘guide’.”

Sarsgaard is truly proud of Memory, a low-budget indie that, as he points out several times, is a “tiny” project that few people have so far seen (it’s only made around $4,000 at the US box office). He’s aware the term “dementia” can be a turn-off. “I frequently don’t even mention that word. When people ask me what Memory is about, I say, ‘It’s kind of an unusual love story.’ Which it is!” He praises Chastain for pushing so hard to get the film made (it was she who urged Franco to cast Sarsgaard). Asked to describe his co-star in one word, he opts for “direct”. What would she say about him? “Intuitive? I know that I’m very intuitive. That’s maybe my main skill.”

One of his favourite pastimes is people-watching. “I enjoy figuring out what the relationships are between people. I go to the park near here and I’ll think, ‘Father-daughter? Nope. Man and lover!’” He pulls a face. “Yeah, it can get weird. You don’t need to listen to the conversation. They say so little of the communication we do between us is verbal. I also like playing chess with strangers in the park. I like trying to read them.”

He thinks he started watching people at a young age. His father was an air force engineer and the family moved a lot. “I didn’t talk very much. I was an only child, I didn’t have anyone to talk to! I was very quiet and still. So it might have been apparent that I was thinking about something other than video games.” Sarsgaard’s maternal grandfather, Phillip Reinhardt, “had the bearing of Robert Duvall or Tommy Lee Jones,” he says. “He was a very tough, Southern man; a mechanic at the fire station. And I was around him all the time and he said almost nothing. We hunted and fished. He’s the one who taught me how to play finger-style guitar. He used to play Mississippi John Hurt and Son House. A lot of African-American music. I felt like I knew him better than I knew anybody and yet I knew nothing about him. Nothing literal.”

Sarsgaard’s way of interacting sounds intense. He nods. “I have a need to know what’s going on with people around me. It might be irritating to live with me, actually, because I’m always spying in one way or another, especially with my kids. I’m always thinking about them.”

He and Gyllenhaal have two daughters, Ramona, 17, and Gloria, 11. Gloria sings and plays the violin, Ramona plays the oboe, accordion and double bass. Sarsgaard moves the camera so I can see the instruments sitting in the corner of the room. “This is what I mainly do with my daughters. We have a little band.”

Sarsgaard’s study looks immaculate. I tell him I interviewed Gyllenhaal when she was first starting out, when she was promoting the dark comedy Secretary (2002). She gave me a piece of advice: always make your bed in the morning, as a “gift” to yourself. Sarsgaard screws up his face. “That’s a great idea. Hmm... I’m thinking about whether or not our bed is made right now. I think the answer is probably.” He looks over my shoulder, into my study-slash-bedroom and says, brightly, “I see that yours is!”

“You know what my advice would be?” he adds. “When you wake up, drink an entire glass of water. That’s helped me out. I think I walked around, dehydrated, for most of my life.”

Just as we’re about to say our goodbyes, Sarsgaard blows a kiss to someone. It turns out his dog, Babette, a wirehaired pointing griffon, is in the room. “Come here, baby!” Sarsgaard croons, before scooping her up. She gives him a series of ferocious licks before he plops her back on the floor. As she trundles off, he shakes his head, fondly. “She’s a real sweetheart. She just wants to be with me all day long.”

Sarsgaard dotes on dogs. And underdogs. In these troubled times, he’s just the softie we need.

‘Memory’ is in cinemas from 23 February