Pusha T: The Rise and Reign of a Self-Made King

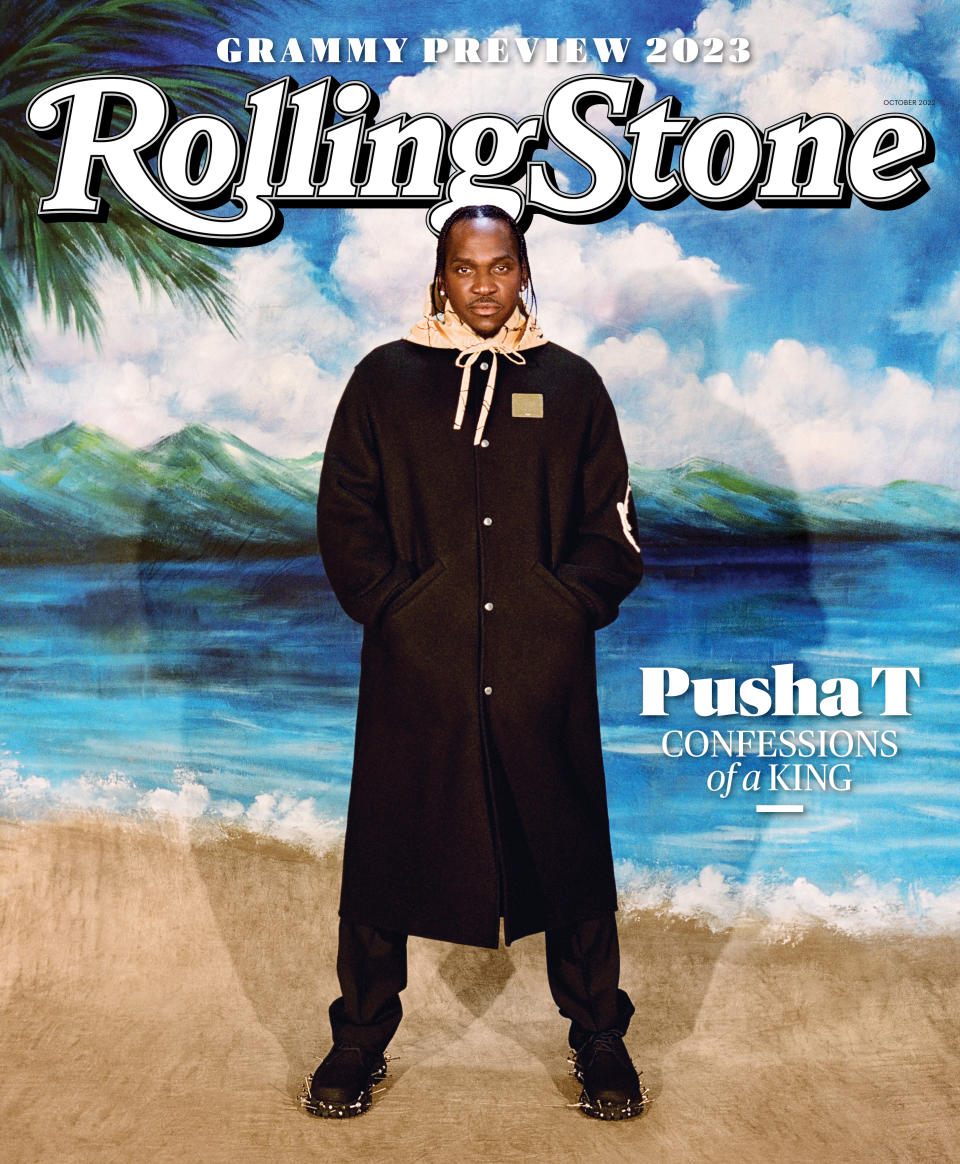

This story is part of Rolling Stone’s third annual Grammy Preview issue, released ahead of the start of first-round Grammy voting on Oct. 13th. We spoke to some of the year’s biggest artists about the albums and singles that could earn them a statue come February, made our best predictions for the nominees in the top categories, and more, providing a full guide to what to watch for in the lead-up to the 2023 awards. Pusha T stars on the issue’s cover.

“…AT A BACHELOR party I didn’t even want to have!” If any of the thumb-faced dudes in expensive suits at Nobu Fifty Seven looked this way, they’d see someone on a whole other plane of style at the table in the corner: a casual king in a black-and-white-striped T-shirt from Marni, loose Balenciaga pants, and tight braids.

More from Rolling Stone

Pusha T flashes a wicked smile as he explains that the platinum Presidential Rolex watch on his left wrist is actually a replacement for one that had been stolen from his hotel room before his 2018 wedding. The party in Las Vegas was all Pharrell Williams’ idea, he says — one more caper in their lifelong friendship, like Ocean’s 11 for Virginia rap legends. But when he got back to his room late that night, the Rollie was nowhere to be found.

“It was an inside job,” he continues, dialing up the suspense. Suspecting a member of the staff, he sued the hotel and recouped the loss. Exactly how he did this is a long story, which he recounts with relish as a waiter at this high-end midtown Manhattan restaurant clears his plates. The big takeaway is that you should never, ever try to cross Pusha T on a matter of property law. “Bought it for $72 [thousand],” he concludes. “Bought it again for $80.”

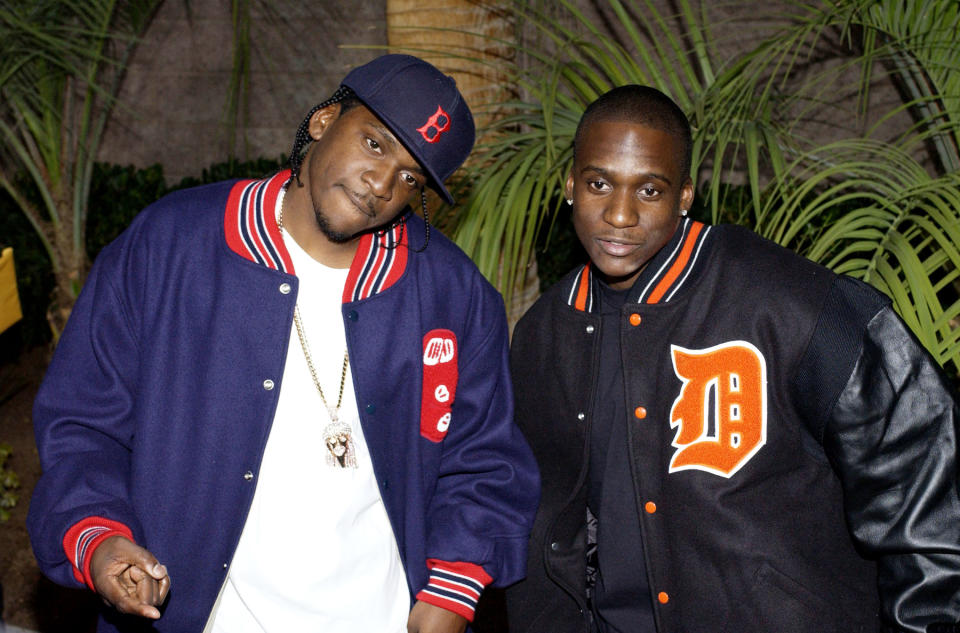

Pusha loves telling stories where he ends up winning, and he’s got plenty of them. He talks about that night in Vegas with the same braggadocious charisma that made him America’s favorite former drug dealer in the George W. Bush era, when he gained fame as one half of the brotherly duo known as Clipse. Pusha, born Terrence Thornton, was the combustible star, the morally ambiguous charmer who never ran out of new ways to describe selling narcotics; his older brother Gene Thornton Jr., a.k.a. Malice, balanced things out with his steady, stern presence. “Malice would always have a wise point of view — his shit was very poetic,” Williams, who has known the Thornton brothers since they were all teenagers, tells me later. “And Pusha was the young, wild one. His shit felt impulsive.”

Pusha has been a solo artist for more than a decade now, since Clipse’s career flamed out and his brother walked away, and he’s only gotten bolder with time. On his fourth album, It’s Almost Dry, the 45-year-old rap phenomenon reaches new heights of dazzling wordplay and devilish storytelling over an immaculate set of beats from Williams and Kanye West. Dubbing himself “cocaine’s Dr. Seuss” one minute, comparing himself to both Superman and Shakespeare the next, he’s never sounded sharper or hungrier. “It tells the story of what I’ve been able to do in the rap game,” Pusha says. “The ability to bring worlds together, the ability to make an event of my music. The ability to give my fans the best possible, highest grade of rap music in its purest form.”

It’s Almost Dry is a must-mention in any online or IRL discussion of 2022’s best rap album — a remarkable feat for an artist who is a solid decade or two older than most of the other likely contenders in that Grammy category. The list of rap artists who have stayed at the top of their game into the second half of their forties is vanishingly short. For Pusha, who’s defied outrageous odds in the music industry more times than he can count, that’s just another challenge to rise to. “We are trying to show that our era of music is the era that does not have to age out,” he says. “We can make this greatness forever. This never has to stop.”

ASK PUSHA HOW he fell in love with hip-hop and he’ll take you back to 1985, in his parents’ home in Virginia Beach, Virginia, where an eight-year-old Terrence Thornton watched his 13-year-old brother Gene fill endless notebook pages with rhymes. “He was the first person I’d ever seen write raps passionately, at a very young age,” Pusha says after taking a seat at Nobu and ordering a light lunch of yellowtail sashimi, king crab tempura, lobster salad, and green tea. “For his attention, I would do things like bend his rap book, or take it and run, and he’d beat me up.”

There was a cultural revolution happening about seven hours north in New York, and the Thornton brothers were enthralled — reading early hip-hop magazines, listening to songs like UTFO’s “Roxanne, Roxanne,” breakdancing in their living room. “Anything related to hip-hop, from fashion to boomboxes, he was fully immersed in it,” Pusha continues. “And as a younger brother, I copied everything he did.”

At the time, Gene was part of a teen rap collective called Def Dual Productions, named for the group’s unusual structure: 30 rappers, paired up into 15 duos. “Of course, the junior high school called it a gang,” Pusha says. “But their thing was to rap, and that’s what they all did. And my brother just happened to be the shining star of this collective.”

Def Dual Productions’ lineup was rounded out by their DJ, a kid from a nearby neighborhood named Tim. A little more than a decade later, he’d send goose bumps down the spine of pop with Ginuwine’s “Pony” and Aaliyah’s “If Your Girl Only Knew” — the first of dozens of stunningly inventive hits he’d produce under the name Timbaland — but back in 1985, his most important asset was a house that was empty most afternoons. Terrence and Gene would ride their bikes over to Tim’s place, where Terrence watched the older boys make music until Tim’s father got home from work and kicked them out each evening. “After Pops came home, then it’s over,” Pusha recalls wryly.

Mildred and Gene Thornton Sr., while loving and present parents, weren’t much more understanding of their sons’ musical interests. “My parents thought it was a joke,” Pusha says. For his dad, who’d served in Vietnam before starting a family in the Bronx and then moving them south in search of a quieter life, spending hours on music just didn’t add up. “My dad was a very traditional, hardworking man,” he adds. “Military, firefighter, mailman — he’d been all those things. Very structured.… They’d say, ‘Oh, you can write this music, but you can’t do your social studies?’ And it fell on deaf ears.”

Hip-hop wasn’t the only thing happening in Virginia Beach in the Eighties. The Reagan-era crack epidemic was in full swing, too — and a risky but profitable business opportunity was there for any kid who wanted it. As with everything else, Pusha says, his brother showed him the way. “I was super impressionable, and I had access to neighborhoods I might not necessarily supposed to be in,” he says. “That introduced me to the streets, introduced me to drug culture.”

He remembers his parents’ disappointment when they turned on the local news to see his brother lurking in the background of a TV report on the worst neighborhoods in town. “My parents would go to the neighborhood and see him outside walking with a hoodie on, probably just made a sale or some shit,” he says. “Things started to make a little bit of sense — his independence, his rebelliousness.”

In the fall of 1991, when Pusha was 14, his brother enlisted in the U.S. Army after learning that he’d gotten his girlfriend pregnant. Back home, Pusha faced less parental scrutiny, enabling a life of Ferris Bueller-esque truancy: “I had my own line in my room that the school would call if I missed school, but it went directly to me.… By the time I was in high school, I never went to school for a full day. I was trying to get money at all costs.”

We are trying to show that our era of music is the era that does not have to age out. We can make this greatness forever.

Pusha remembers debating the merits of Biggie, Wu-Tang, Mobb Deep, and Snoop with the diverse crowd of friends and customers he’d cultivated by the mid-Nineties. “I’d meet older people who were smoking weed; white kids that I was going to school with were doing acid,” he says. “We bonded over hip-hop.”

He was careful, though, not to tell his closest peers that he’d begun writing lyrics of his own. “We were listening to everything, arguing who was better, but to actually say you’re doing it? My friends would be like, ‘Man, if you don’t get the fuck out here and come get this fucking change …’ The fully-engulfed, New York-to-Virginia-pipeline level of foolishness — that was the coolest thing to be doing.”

On “Let the Smokers Shine the Coupes,” a pulse-racing, paranoid highlight of his new album, Pusha rhymes the title with the words “the dope game destroyed my youth,” hinting at the darker costs of those years. “It grew me up super early,” he tells me, growing somber. “I was introduced to addiction. I was introduced to adolescent death. We had friends who would get killed, some kids who jumped out a little bit further. Jail time. I feel like I was introduced to a lot of things that I took for granted — come to find out, later in life, it’s a bit systematic.”

He stresses that selling drugs wasn’t a choice driven by desperation for him; his family provided a steady lower-middle-class environment, and most of his friends could say the same. “We all had a pretty decent upbringing. Some better than others. But it wasn’t a rough-and-tumble thing. Everything that was done was out of greed and mischief.”

A more positive influence came from Williams, another member of their unusually talent-rich friend group with whom he’d become close a few years earlier. “Hip-hop aficionado, Tribe Called Quest junkie,” Pusha recalls. “One day he came to me and said, ‘Hey, I just found out that your brother is Gene. He’s one of the best rappers I’ve ever heard. Can you hook me up with him?’ And I was like, ‘Nah, he works with Tim.’”

But Williams was persistent, and eventually he talked the Thorntons into coming to meet his buddy Chad Hugo, forging a connection that deepened after Gene returned from the Army in 1994. Williams recalls Pusha hanging out on the margins of their afternoon-long sessions at the Hugo family house (which, much like the ones across town at Timbaland’s place, ended whenever a parent got home). “He used to fall asleep on the couch while we were working,” Williams says. “He’d be watching all kinds of crazy Japanimation, a lot of which I haven’t seen in years. He was just Terrence at the time. And then he decided he wanted to rhyme.”

Listening to the brothers trade verses one day on a track called “Thief in the Night,” Williams was struck by a bolt of inspiration. “Pharrell had this bright idea,” Pusha says. “He was like, ‘Man, y’all going to be a rap group. You remember Kane & Abel? This is going to be harder than Kane & Abel’” — referencing a pair of rapping twins who were making noise on No Limit Records at the time.

The newly formed duo called themselves Full Eclipse until they got wind of another group with a similar name and shortened it to Clipse. Williams was their biggest cheerleader. “I used to always tell him, ‘Man, you’re really good at this, you could actually make a living with this,’” the producer recalls.

But the allure of easy money called to Pusha. “He was stepping into the street life and being enamored with it in a super real way,” Williams adds. “At that time, pushing weight was the greatest thing. He really got into the idea of what that could look like for him.”

After high school, Pusha spent a year enrolled at Norfolk State University, torn between two paths forward. “My first year, I had a good friend who was a little older,” he says. “He was one of those people who would move to a city, buy an apartment, set up a whole shop, open from 9:00 to 6:00. He’d call me: ‘Hey, listen, can you sit here and keep my clientele going for the hour?’ And me, I’m scared to death. I’m like, ‘All right, I’ll come, but I’m leaving by dark.’ Just youthful, hardheaded, risk-taking decisions.”

He went by the rap name Terrar on an unreleased Clipse album, Exclusive Audio Footage, that got shelved by Elektra Records in 1999. “We put a single out called ‘The Funeral,’ and that didn’t work out,” recalls Williams. “And then it went from Terrar to Pusha T — ‘push a ton,’ that’s what it stands for.”

By this time, Williams and Hugo — who’d taken to calling themselves the Neptunes — were becoming a major force in hip-hop production, selling brash, attention-grabbing beats to East Coast rappers like Noreaga, Ol’ Dirty Bastard, and Jay-Z. The Thornton brothers’ 2002 debut, Lord Willin’, released through the Neptunes’ Star Trak imprint, became a laboratory for the producers’ most out-there ideas. “We loved making the shit that we felt like didn’t exist,” Williams says. “It needed to have an element of alien to it, because it came from us, the Neptunes. It was going to be rap, but it was going to be a little bit left of center.”

“Grindin’,” the album’s first single, featured a jarringly minimal beat — like a car door slamming or a clenched fist banging on a wall — along with an instantly memorable opening verse from Pusha: “From ghetto to ghetto to backyard to yard, I sell it whipped or unwhipped, and soft or hard …”

“It was a major disconnect when we came out, talking about what we were talking about,” Pusha says now. “Local radio stations were telling Pharrell, ‘If you let me remix it, I’ll play it.’”

But “Grindin’” became a word-of-mouth success, resonating with an untapped audience. “We would go across the country doing shows — $2,000 shows, $3,000 shows, $1,500 shows for some guy who’s getting money in his neighborhood, and only his neighborhood would be in the venue,” Pusha says. “Forty people, and they would want us to do the song nine times. They knew what it was.”

In time, “Grindin’” became one of two certified Top 40 hits from the album. Just as important to the fans were album cuts like “Virginia,” where Pusha and Malice paid tribute to the street economics of their Southern home over a rich, honeyed Neptunes instrumental. “Just image-wise, two dark-skinned brothers out of Virginia, you know what I’m saying?” Williams says. “We looked at what the average person of our persuasion was going through, and they were able to communicate that.”

As the decade went on, though, Clipse were dealt hand after hand of terrible industry luck, infamously getting caught in label-merger purgatory for years before releasing their second album, Hell Hath No Fury, on Jive Records in 2006. “These are the days of our lives, and I’m sorry to the fans,” Pusha rapped, “but them crackers weren’t playing fair at Jive.”

Though it met with underwhelming sales, the album stands as a masterpiece of high-stakes lyrics and high-art production. “The darkest moment made Hell Hath No Fury, which is by far the best album, rap-wise,” Pusha says. “The bullshit was the bullshit — the label drama, the frustration. Listen, that’s how strong we were musically: Even through the frustration, we still got Hell Hath.”

It wasn’t as easy for his brother to rationalize Clipse’s treatment. “He felt like he was cheated out of opportunity and time,” Pusha says. “He was used to success — popular success, versus critically acclaimed success. And he felt that both could have coexisted if he hadn’t went through the ringer of the label shit.”

Pressure on the group mounted when several close associates, including a former manager, were sent to prison in 2010 for their alleged role in operating a $20 million cocaine, weed, and heroin ring alongside Clipse’s rise. In 2009, after yet another label switch, Clipse had released a third album titled Til the Casket Drops. Less than a year later, after a show in Scandinavia, Malice had something he needed to tell Pusha.

“My brother told me that he didn’t want to be in the group no more,” Pusha recalls. “He was like, ‘You’d be better off solo. You should do your thing. And I’ve been writing this book. Here, read my book.’”

His brother’s book, published in 2011 under the title Wretched, Pitiful, Poor, Blind and Naked, detailed Gene’s internal battles on the road to a profound Christian faith. Soon, the elder Thornton would reemerge with an album of devotional rap and a new stage name, No Malice, complete with a video quoting a New Testament verse: “Let all bitterness and wrath and anger and clamor and slander be put away from you, along with all malice.”

For Pusha, none of this was a surprise: “If you listen to my brother’s music through Clipse, he’s always had this religious undertone. We called him the voice of reason.” Even the album name Lord Willin’ — and the cover art, depicting the Thornton brothers driving a convertible with Black Jesus in the back seat — had been his brother’s idea.

Just as important, his brother was married with two kids by this time; Pusha was at a different place in life. “‘You know what?’” he remembers thinking. “‘Fuck it. I could hustle a little bit.’”

A FEW DAYS after the conversation that put Clipse on a decade-plus pause, Pusha got a call from Kanye West. They knew each other, but not well — the Chicago rapper-producer, a serious Clipse fan, had invited them to perform as the featured entertainment at his 30th-birthday party at Louis Vuitton’s New York flagship store in 2007, and had guested on a track on their final album. Now, he was inviting Pusha to fly to Hawaii to work on the sessions for what became My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy.

It was a friendly offer that arrived at exactly the right moment for Pusha, launching a second and more successful phase to his career that continues to this day. At the time, though, it was a shock to the system. Pusha, used to the Neptunes’ precision in the studio, had to adjust to West’s more open-ended approach to creativity, with upwards of a dozen musicians in collaborative competition.

“I had never worked like that before,” he says. “Very trial and error — try everything, exhaust all ideas. I think I said something great? He wants to say something greater. And greater might take another two hours, three hours, four hours. When I was writing ‘Runaway,’ I thought my first verse was great. It was my ninth one that was great.”

Pusha signed to West’s G.O.O.D. Music as a solo artist in the fall of 2010, initiating a refreshingly stable relationship that has yielded four acclaimed albums, including 2018’s Grammy-nominated Daytona; in 2015, he was named the imprint’s president. While West’s public image has taken a number of baroque twists and dispiriting turns in the years since then, Pusha’s albums have remained one of the last places where a listener can tune all of that out.

“Everybody’s like, ‘Oh, I love the old Kanye,’” Pusha says over Zoom a few weeks before our lunch. “Well, when you hear Pusha T, you hear the old Kanye.” It’s true — to hit play on It’s Almost Dry is to enter a dimension where Kanye isn’t a MAGA dabbler, a friend of Tucker, an obsessive ex-husband, or a guy who believes in the spiritual redemption of Marilyn Manson. He’s just a wildly gifted producer, a magician on the MPC who can keep looping a sample of Beyoncé or Donny Hathaway’s voice until it touches heaven.

Pusha is similarly proud of his work with Williams on this album, their creative mind-meld still serving up new rewards after nearly 30 years. “It’s not ‘Happy’ Pharrell,” he adds. “It’s Lord Willin’ levels, Hell Hath No Fury levels of greatness that cater directly to the hip-hop purist.” In fact, Pusha is taking this Zoom call from a car in South Beach, Miami, where he’s on his way to meet Williams at a studio and work on something new. (“I don’t want to give anything away,” Williams says later when I ask what they got up to. “But the giggles are even more evil than they were the last time.”)

Pusha’s diplomatic about his Best Rap Album loss to Cardi B’s Invasion of Privacy at the 2019 Grammy ceremony — “Cardi definitely had the energy going that year” — and says he’ll be there in Los Angeles next February if It’s Almost Dry earns any nominations. “I’m of the era where guys would boycott the Grammys,” he says. “I witnessed when hip-hop wasn’t shown on television.… I want to show up, just to show how times have changed.”

One thing he’s adamant about: He wants to be celebrated for the music he’s making right now, not nostalgia for his past peaks. “I don’t want a lifetime-achievement award,” he says. “If I’m not doing hip-hop at a high level, I won’t do it anymore. And it’s fine. But the fact that the music is coming out like it is — that’s my new marathon, to show how long I can keep going at this level.”

DESPITE THE DIVERGING paths their careers have taken since 2010, Pusha and his brother have always remained close. “I talk to my brother every day,” Pusha tells me toward the end of lunch at Nobu, as he’s told countless interviewers who have asked a version of this question over the past decade.

These days, they have to stay in touch to coordinate care for their older sister, who has a health condition — a hardening of the arteries in her brain — that requires constant support. “She’s not mobile, but she’s really sharp,” Pusha says. “So she’s in a nursing home, and me and my brother mutually take care of her with the nurse every day.”

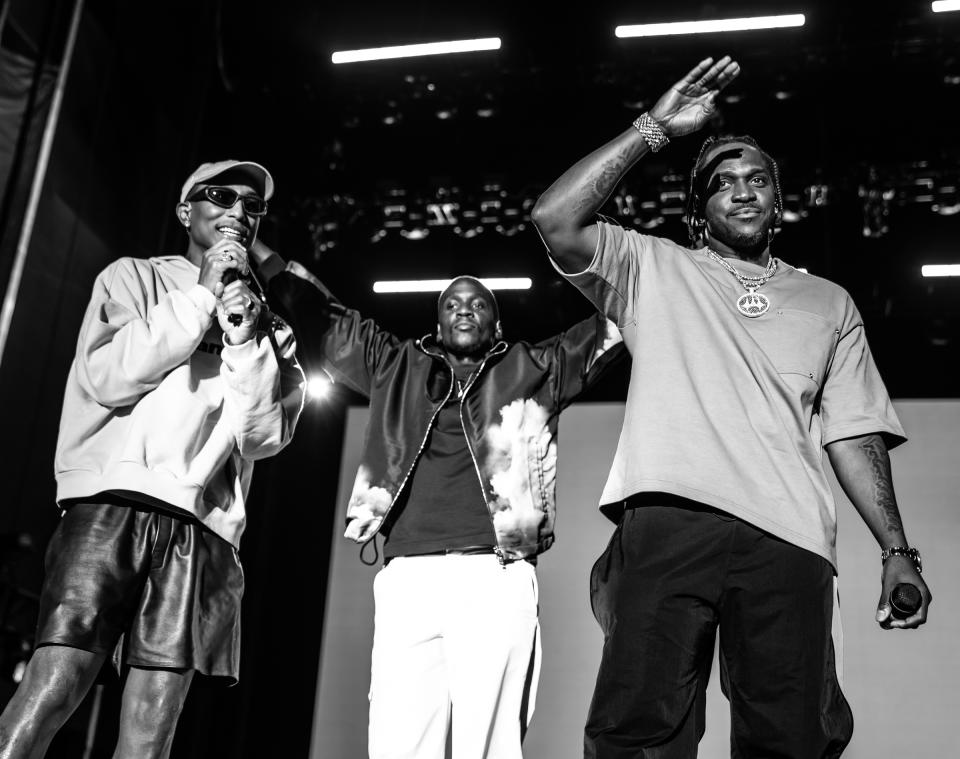

But they also talk about music — and since 2019, when the Thornton brothers were featured guests on a song called “Use This Gospel,” from West’s religiously-themed album Jesus Is King, Clipse fans have been fiending for any crumb of news about a potential reunion. Those rumors heated up this year, when Gene, calling himself Malice again, contributed the verse that closes out It’s Almost Dry: “Tell me what I missed,” the elder brother begins, flinty and tough as ever. “Vietnam flashbacks, I get triggered by a sniff/Today’s top fives only strengthening my myth.” In June, they performed a four-song Clipse set at Williams’ Something in the Water festival in Washington, D.C., to rapturous reviews; a few weeks after Pusha speaks with me, they’ll pop up in Atlanta at the BET Hip Hop Awards and bring the house down with “Grindin’.”

Pusha says he frequently encourages his brother to commit to a full Clipse reunion. “I push the button every so often,” he says. “I’m like, ‘Yo, listen to what I just made! We can really do this’ — and he brushes me off.… If I had it my way, it would be the Clipse. It’s really up to my brother.”

In the meantime, they connect as they always have, as family. Gene is a devoted uncle to Pusha’s two-year-old son, Nigel Brixx Thornton. At a recent studio session with his brother, Pusha recalls, he mentioned that Nigel was running a fever. “Studio session halts. He’s like, ‘You got to get that fever down.’ I’m like, ‘OK.’ We’re getting back to work: ‘Yo, did you get the fever down?’ He’s fully in tune.”

Pusha pulls out his iPhone to show me a text from his wife, Virginia Williams: “Nigel had a great day,” with an eyes-welled-up emoji. Being a father has transformed his life, he says. “Parenthood, man, it’s made me so focused,” he says. “There’s nothing that I want more than to get back home to my family. Nothing.”

Family has become even more important to Pusha since he lost both his parents in rapid succession over the past year. “My mom was sick, and my dad was sudden, right after my mom,” he says. He’s happy that they both got the chance to meet their new grandson: “He won’t remember, but it gives me a little bit of peace.”

The death of Gene Sr. this past spring made Pusha reflect on the role that his father played in his life. “All of my friends were really broken up about my dad,” he says. “I’m talking about all of my friends, from the worst to the best of them. And we have a lot of worst to the best. They told me, ‘Damn, man. He was like my dad.’ He’s always been like that for a lot of people. I really had a dad, like a real one.”

It’s an example that Pusha’s thankful for as he approaches his own middle age. “My dad was a roll-with-the-punches guy,” he says. “You could tell him anything happened that was wrong, and he’d be like, ‘OK, so what the hell are you going to do? What’s next?’” Pusha checks his Rolex and rises to head out to a rehearsal for his fall tour of North America. “We don’t wallow in any type of bad situation,” he adds. “We keep pushing through.”

Production Credits

Photography direction by EMMA REEVES. Fashion direction by ALEX BADIA. Market editor: LUIS CAMPUZANO. Styling by MARCUS PAUL, assisted by JADA STOUDEMIRE, KIMBERLY INFANTE, and KYLE RICE. Grooming by SAREEN BHOJWANI for Exclusive Artists Management. Set design by DANIEL HOROWITZ for Jones MGMT. Produced by JOE RODRIGUEZ.

Best of Rolling Stone