"We would go out and he really never wanted anybody to know that he was a musician": The troubled life and lonely death of Peter Banks, the man once called "the architect of prog"

High Barnet, on the suburban cusp of North London and Hertfordshire, seems like an incongruous place for one of prog rock’s founding fathers to have spent his last days. But it was here, in March 2013, between the affluent high street and green woodlands, that Yes co-founder and original guitarist Peter Banks died.

Banks wasn’t quite a recluse, but he had long ago removed himself from public life and returned to the house he grew up in. For several years this pioneering musician had surrounded himself with just a handful of friends and associates, many of whom had no idea of his past.

One of the ones who did was Leigh Darlow, a local dance music producer and DJ. On Wednesday March 6, Darlow drove to Banks’s rented flat at 37 Alston Road and banged on the door. He was concerned after Banks failed to show up for a session at Darlow’s studio, Earthworks.

“At that point I was a bit worried,” Darlow says today. “I mean, he was well, because he was still doing sessions. But I did think, ‘I wonder if he’s had an accident.’”

The next day, Darlow discovered the truth. Banks’s upstairs neighbours suspected something was amiss. “They were used to hearing him downstairs and they hadn’t heard him, so they called the ambulance,” says Darlow.

On entering the house, they discovered Banks’s body. The coroner later declared that he had died from heart failure, though it emerged he was suffering from other health problems. But for Banks’s few close friends, the 65-year-old’s death was the start of a testing time that saw his body lying unclaimed in the local mortuary..

There’s a ‘sold’ sign outside 37 Alston Road now, though the downstairs flat with the unkempt green window frames is at odds with its salubrious surroundings. The flat itself represented Banks coming full circle.

“What I’ve always found intriguing was that Peter’s mum and dad got married in 1938, and they moved into that flat,” says George Mizer, Banks’s Ohio-based business partner and informal manager, whose relationship with the guitarist stretched back to his post-Yes band, Flash. “It was the only place they ever lived – that just blows my mind. Peter was born in that house and Peter passed away in that house.”

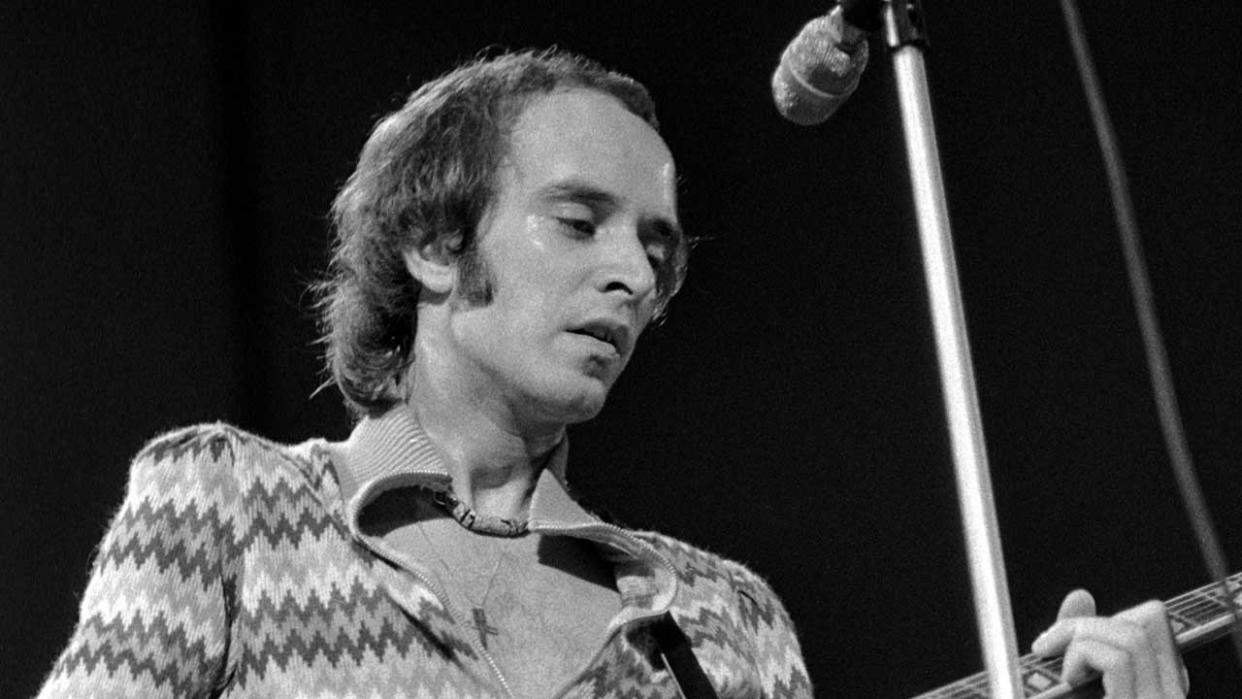

For at least a few years in between, Banks – born Peter William Brockbanks – put a few thousand geographical and metaphorical miles between himself and the flat. As an original member of Yes he was a key part of both that band and the nascent prog rock movement. He christened the band – supposedly as a temporary measure – and played on their first two albums, 1969’s Yes and the following year’s Time And A Word. Broadcaster Danny Baker described him as "the architect of prog".

To George Mizer, his innovation was to introduce “a kind of jazz influence, intertwined with the hardness of the guitar sound”. Play Astral Traveller, from Yes’s second album, and you’ll be struck by the cleanly rotating guitar riff that complements keyboard player Tony Kaye’s space-rock organ. “Tony came up with a wonderful little statement,” says Mizer. “He said that Yes would have been a Maybe without Peter.”

But, as with many aspects of Banks’s career, it was fleeting. Following Time And A Word, the guitarist was ousted from the band, along with Kaye. The pair supposedly objected to singer Jon Anderson supplanting many of their recorded parts with an orchestra.

“Of course he was bitter for the longest time, but he stayed in contact with Jon,” says Mizer. “They would talk about old times every once in a while, and laugh and say: ‘We’ve got to do this,’ and it just never really happened. Kind of a ‘what if…’”

Following his departure from Yes, Banks formed Flash, which is when George Mizer met him. The American booked the band to play Akron, Ohio, in 1972 and befriended the guitarist. It was an association that lasted until Banks’s death, former record store owner Mizer keeping the flame burning when the music industry at large had all but forgotten him.

“We spoke at least five days a week,” says Mizer. “He was kind of unsure of himself towards the end. He’d been sick for three years. I think he wanted to get things in order, music-wise.”

For Banks, this partly involved remastering the tapes of a Flash show from the early 70s for a live album, Flash In Public. It was released posthumously at the end of 2013. The album included a version of that band’s minor US hit, the jazzy, space rock of Small Beginnings.

Flash wasn’t Banks’s only post-Yes project. In 1973 he released an instrumental solo album, Two Sides Of Peter Banks, featuring guest appearances from Genesis’s Steve Hackett and Jan Akkerman of Focus. Pre-dating Tubular Bells, it married a series of evolving themes via a mix of improvisation and editing.

“He worked a lot like that,” says Mizer. “He had a project in 2000 where he re-did Small Beginnings, and he sent it to me on cassette. There were forty-three different little snippets that might have been twenty seconds long, and he pieced it together.”

Banks’s final foray into the band format came with Empire, who put out three albums between 1973 and 1979. The band was fronted by an American singer named Sydney Foxx. The glamorous blonde soon became the first Mrs Banks.

“I knew Sydney from being on the road,” recalls Mizer, “when it was just, ‘There’s Peter with a chick’, kind of thing. These things altered when we were in our fifties. Then it was, ‘There’s Peter’s wife Cecilia.’

Cecilia Quino, Banks’s second wife, was a Peruvian Yes fan who spent much of her time in the US. “I think he met her in ’96, at the Yes Convention in Philadelphia,” says Mizer. “They jetted back and forth, Peter went and visited her in Lima, and they got married then.”

During the 70s and 80s, Banks worked as an in-demand session musician in LA (he played on Lionel Ritchie’s hit 1984 album Can’t Slow Down, among others). But family problems forced him to return to London in the 90s.

“He returned home because his dad was ill,” explains Darlow. “He did look after his dad for a bit, but he died shortly after. When I first started getting to know Pete better in the early 2000s, he was in his place on his own. His parents weren’t around at that point.” Neither was Cecilia, their marriage having been short-lived.

Leigh Darlow first got to know the guitarist when his came into Darlow’s Earthworks studio with his instrumental group of the time, the Harmony In Diversity Band. Banks had sunk into relative obscurity in the 90s, releasing three solo albums and contributing to various tribute albums, but Darlow was unaware of his past as one of prog rock’s progenitors.

“He definitely wasn’t somebody who’d shout about what he’d done,” says Darlow. Despite their different musical backgrounds, the pair forged a friendship and gradually became closer, especially over the last three years of Banks’s life. Darlow remembers his friend’s domestic set-up as “kind of sketchy”, with a gas bill from years ago left lying on the table (even today, BT lists a phone number for William Brockbanks, Peter’s long-dead father, as if his son had never been there at all).

“He was still doing paid session work. It was really keeping him going,” says Darlow. “But he wasn’t that great, healthwise. I ended up going round his house, picking him up, then taking him home and making sure he was alright. I tried to make it as easy for him as possible.”

Darlow describes Banks as a man “without a bad bone in his body”. George Mizer backs that up. But Mizer adds that Banks had his insecurities. “I didn’t think he was comfortable,” he says. “We would go out and he really never wanted anybody to know that he was a musician.”

This unassuming attitude extended to the state of his health, which Banks seemed to regard with indifference.

“He suffered from depression and stuff like that,” says Mizer. “He started losing some of his teeth and he had blood poisoning, septicaemia, so he went into hospital. It wasn’t unusual for me not to be able to talk to him sometimes. He would get into a dark area maybe around February or March. And I thought this last year he must be having a tough time. Then he finally called me: ‘Oh, they found this tumour, but I’m leaving the hospital. I don’t know if I’m gonna go back.’ I said: ‘You gotta go back.’ The doctor said: ‘Don’t let it go, because it won’t get better on its own.’ And that’s just what he did.”

Mizer believes Banks’s continued neglect of his dental problems poisoned his system, leading to the heart failure that killed him, rather than the tumour.

“We were together in September 2012, and when we left he gave us a hug – my wife and me and another friend,” says Mizer. “I got an eerie feeling like, ‘I don’t think I’m gonna see him again.’”

When Leigh Darlow heard that Banks had died, his first response was to break the news to George Mizer. The latter found himself in the impossible situation of conducting his client’s posthumous business from the other side of the Atlantic.

“I couldn’t get the body released,” he says. “They wanted family – well, there’s no family left, and Peter always said he wanted me to handle everything. I said to him: ‘You’ve gotta write that down.’ But they found nothing – no will or anything in writing. We did the best we could, but at that time I couldn’t find Cecilia.”

Although the couple had split, Banks and his second wife retained an amicable relationship. Cecilia was still living and working in London, but at that point she was visiting her parents in Peru.

“I told her what had happened on the phone and there was silence,” says Mizer. “She just said she didn’t want to deal with it. I figure it was the shock at first.”

For Darlow, the days following Banks’s death were no less frustrating. “They’d taken his body away to the mortuary,” he recalls. “When I was doing the rounds, nobody had a trace of him. Then somebody went, ‘Oh, Brockbanks.’ There were a few days he kind of went missing because nobody had contacted them.”

When Cecilia returned to Britain, she gave her approval for the body to be released. But this threw up another problem. By the time of his death, Banks had left no financial assets to fund his funeral and commerative wake.

“Peter rented that flat all those years. It was never owned,” says Mizer.

Instead, Mizer decided to shoulder the responsibility for his friend’s send-off. This took the form of an online appeal for fans to contribute to the costs of the funeral.

“I don’t want you to think George Mizer paid for it all out of his own pocket,” he insists with gruff charm, “that wasn’t the case. We were able to do something because [the fans] stumped up – even though some old band members didn’t.”

Banks’s body was cremated during a small service, after which Mizer, Darlow, Cecilia and other associates of the guitarist had a memorial drink on London’s Denmark Street. Also in attendance were David Cross of King Crimson, Wishbone Ash’s Dave Wagstaffe and original Yes manager Roy Flynn.

“It was very moving to me,” says Darlow. “It was almost like Peter didn’t have any friends towards the end. But the friends were there again, talking about the old times, laughing about Tony Kaye and Peter. Apparently they drew straws to see which one of them would have to sleep with Janis Joplin after a gig at the Royal Albert Hall.”

Mizer still keeps his friend’s ashes close to him, occasionally sprinkling a handful of them in places that meant something to the guitarist: in Denmark Street, where he first met Chris Squire all those years ago; outside the old headquarters of The Beatles’ Apple company on Savile Row (in their early days Yes met with Paul McCartney about signing to that label); on Waterloo Bridge (“He always said the Davies brothers were wankers, but he probably liked that song,”

Mizer says with a laugh). Mizer also scattered some of the ashes in the beer garden of the White Lion, Banks’s local pub in Barnet. When Classic Rock asked the White Lion’s landlady if any of the musicians who play the pub’s open mic night knew him, she replies: “I’ve asked regulars who have drank here for thirty years and no one recognises the name.”

According to George Mizer, that’s exactly how Banks would have wanted it. He would never have announced himself to anyone, especially fellow musicians.

In 2017, Yes were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame, a belated recognition for their achievements from the music establishment. And Peter Banks was a crucial part of those early triumphs. “The one who came up with the name," says Mizer, "the original logo – it was all Peter."

The following year, work began on Claiming Peter Banks, a documentary about his life, featuring interviews with Mizer and the likes of Steve Hackett, Jon Anderson, Oliver Wakeman, Trevor Rabin and Thijs Van Leer. With principal photography now complete, producers are appealing for funds to finish the project.

Mizer admits that he still has the urge to call up his friend and talk to him. “I actually did phone him up and hear: ‘Peter can’t take your call right now,’” he says wistfully. “I know a lot of people will think that sounds crazy, but Peter was just kind of a lonely guy at times. I was always ready to listen, and I guess I’ve become a good listener.”

Leigh Darlow feels a similar way about his absent friend. “When I’m driving home I always take a look at his house,” he reflects. “My heart drops a little bit. He had a big impact on the studio and everything.”

In fact the only person who might not have detected an element of tragedy in all this is Peter Banks himself. He seemed stoically accepting of the turn his life had taken – perhaps secretly secure in the knowledge that, ever since he introduced those elaborately ascending chord sequences into modern music, he’d played his part in changing it forever.

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 193, in February 2014.