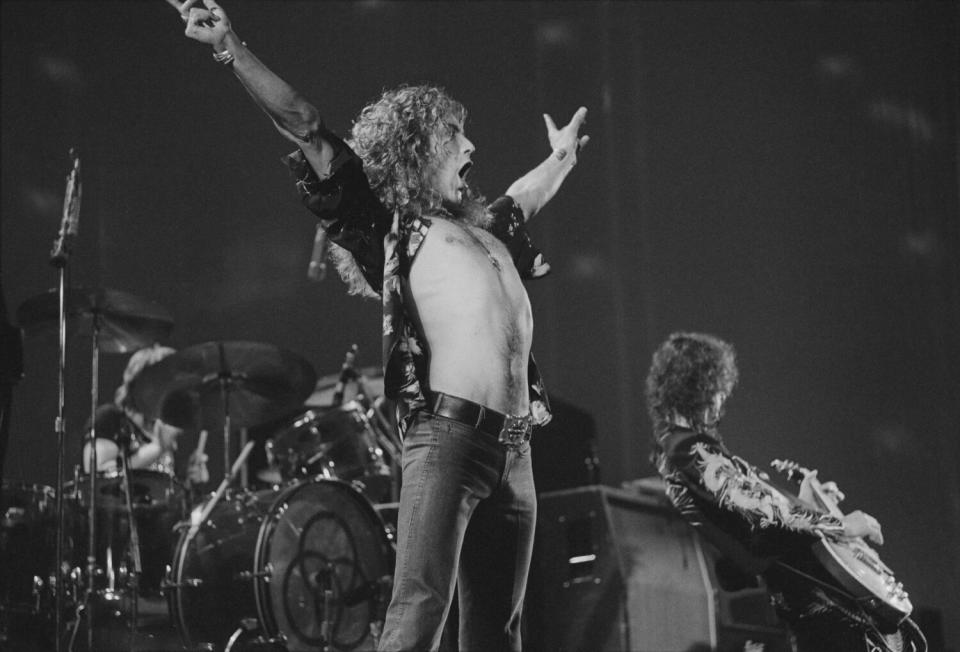

Robert Plant and Alison Krauss on the secrets to aging gracefully

Robert Plant picked up the phone at his home in western England and offered a detailed weather report as he peered through a picture window in a sitting room.

“It’s a beautiful evening here,” said the 73-year-old singer best known as the golden-god frontman of Led Zeppelin. “That said, in the U.K. we’re unaccustomed to 38 degrees Celsius” — about 100 degrees Fahrenheit — “which is what’s been going on today. There’s a major panic around the country with the water supplies.

“So: lovely, but also a little ominous.”

The description isn’t a bad one for the music Plant makes with Alison Krauss, the veteran bluegrass singer and fiddler he met nearly 20 years ago when they sang together as part of a Lead Belly tribute concert. In 2007, the two teamed with producer T Bone Burnett for an album, “Raising Sand,” which showcased their haunting vocal interplay in lushly arranged roots-music renditions of old songs by Gene Clark, Allen Toussaint, Townes Van Zandt and the Everly Brothers. Commercially speaking, the LP was hardly a sure thing (though Burnett had recently overseen the smash soundtrack for “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”); nevertheless, “Raising Sand” went on to sell more than a million copies and win six Grammy Awards, including album and record of the year.

Now, Plant and Krauss, who’s 51, are on the road behind a long-awaited follow-up, “Raise the Roof,” which came out late last year — inside the eligibility window for the upcoming 65th Grammys — yet sounds like it could’ve been made just weeks after its predecessor. Produced again by Burnett, who assembled a top-flight band including guitarists Bill Frisell and Marc Ribot and drummer Jay Bellerose, the gorgeously spooky “Raise the Roof” features more tunes by Toussaint and the Everlys along with oldies by Bert Jansch, Anne Briggs and Merle Haggard; it also has an original by Plant and Burnett, “High and Lonesome,” and opens with a relatively new song in “Quattro (World Drifts In)” by the Arizona-based indie-rock band Calexico.

Krauss, who recently lent her vocals to Def Leppard’s latest album, joined Plant on the call from Nashville ahead of the duo’s Thursday night show at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles.

How would you describe your relationship beyond the music?

Krauss: We’re happily incompatible.

Plant: That’s probably right. I do still like you, though.

Krauss: I still like you too!

Plant: We’re not Dale & Grace or Sonny & Cher, but we’ve definitely got something going on. We’ve got two totally different lives running. Alison’s a lot more private than I am. I’m out in the flood. I’ve lived where I’ve always lived.

You've both been singing for decades. Talk about how you take care of your voices.

Plant: I don’t. I just go out and sing. I know a guy from a famous band that Alison’s quite friendly with — he’s gonna pour some sugar on me or something — who creates a complete hullabaloo backstage. I was back there one time and he was making such a bloody noise. I said, “Why are you doing that?” He said, “I’m warming up.” I said, “Well, you won’t have anything left by the time you get there.”

A voice changes over time.

Plant: I know that the full, open-throated falsetto that I was able to concoct in 1968 carried me through until I was tired of it. Then that sort of exaggerated personality of vocal performance morphed and went somewhere else. But as a matter of fact, I was playing in Reykjavík, in Iceland, about three years ago, just before COVID. It was Midsummer Night and there was a festival, and I got my band and I said, “OK, let’s do ‘Immigrant Song.'” They’d never done it before. We just hit it, and bang — there it was. I thought, “Oh, I didn’t think I could still do that.”

Plenty of fans would love to hear you do it with Led Zeppelin.

Plant: Going back to the font to get some kind of massive applause — it doesn’t really satisfy my need to be stimulated.

Does that make you feel like an outlier among your classic-rock peers?

Plant: I know there are people from my generation who don’t want to stay home and so they go out and play. If they’re enjoying it and doing what they need to do to pass the days, then that’s their business, really.

You and Alison recorded your two albums at Nashville’s Sound Emporium Studios, and you returned there for an NPR Tiny Desk Concert. Why always work in Nashville and not in England?

Plant: I’ve been making records and traveling through America since 1966, and we just don’t have the flexibility that American players do. The culture here and the schooling — English players haven’t been exposed to the wide variety of music forms that are in the States. If Allen Toussaint were around and it was another time, maybe we would have gone to New Orleans and tried to pick up on where he was going with Betty Harris and people like that. But in the U.K. we don’t have that lineage of music — of telling a musical story.

Krauss: I love Fairport Convention and skiffle and all the things that came from that. I appreciate the land that it came from. And the rock ’n’ roll singers that come out of that area of the world — Paul Rodgers and Frankie Miller — they always reminded me of the Ralph Stanley kind of singers. There was always a link for me between the way they sounded and what I would see in my head when they sang.

What’s the link?

Plant: To my mind, with the guys from the northeast of England — Paul and Frankie and Eric Burdon and Joe Cocker — it was all about the blue notes, same as the Stanley Brothers. It’s that flattened third in the scales, which ultimately leads back toward Bert Jansch and Davey Graham — a sort of British transposing of the folk music that was present before the Industrial Revolution and made its way across to Kentucky and West Virginia. Many of the songs we do are blueprinted on both sides of the Atlantic.

Is the point of Plant & Krauss to delineate those historical through lines?

Plant: It’s not just a historical monument, though. What’s the album by Rod Stewart? “The Great American Songbook”? I mean, “Come Fly With Me” is fine. But the guys from Calexico, they’re giving us the new American songbook. Their records “Feast of Wire” and “Garden Ruin,” they’re echoing the circumstances in contemporary America. I have a little blue book that I carry with me everywhere and continue to add songs — threads for the future, if you like — because with access to music now, you’re hearing new stuff all the time.

Which kind of encourages an ahistorical perspective, right? It’s so easy to hear something without understanding what it was building on.

Krauss: But isn’t that part of it? You don’t know why you love something — you just love it. It seems very natural and innocent.

T Bone Burnett recently introduced a new audio format that he says represents the “pinnacle of recorded sound.” Is high fidelity particularly important to the two of you?

Plant: Eh. I prefer something that crackles and bangs. I don’t mind if it sounds like it had a better time earlier in its life. I just want to hear what the musicians and the engineer and the producer at the time were going for. I’m sitting here looking at all these records I got from these record stores in Oslo when Alison and I were playing in Scandinavia last month — fantastic compilations of Muscle Shoals country-funk, stuff by Gregg Allman, some of Cher’s early recordings when she got down there. Remember when Otis Redding was a driver for that session with whoever it was, and everybody went to lunch and he got up and sang, and suddenly we had a new voice on the planet? For me as a listener, I just want to hear the spirit.

Last thing: Don Everly died last year, which means very few of early rock’s pioneers are still living. Obviously their music lives on, but what does it mean when the actual people are gone?

Plant: It’s tough, isn’t it? Great players remain, but maybe it’s a different kind of romance that we’re left with now.

Krauss: We recently lost [the bluegrass guitarist] Tony Rice, who was a huge influence, and I couldn’t believe how hard that hit me for so many reasons. Those people that made you who you are — when they go, they take some of you with them.

Plant: That’s exactly right. I remember when Bo Diddley passed, I was on a bus somewhere with Buddy Miller. It came on the radio and it was like the whole bus just slumped. I mean, Bo Diddley and Chuck Berry — they’re part of your DNA, you know? As British kids, we spent our adolescence just furiously ruining their songs.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.