‘Schindler’s List’: An Oral History of a Masterpiece

“Schindler’s List was never a cure for antisemitism,” emphasizes Steven Spielberg. “It was a reminder of the symptoms of it.”

These days, tragically, antisemitism is all over the headlines: Neo-Nazis chanting “Jews will not replace us” in Charlottesville. The Tree of Life Synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh. The Oct. 7 terrorist attack on Israel that claimed the lives of some 1,200 Jews, the largest slaughter since the Holocaust. Not to mention a former and possibly future American president using Hitler-like language at his Nuremberg-esque rallies, referring to immigrants as “vermin” who are “poisoning the blood” of America.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

All of which is why, 30 years after Spielberg won best picture and best director for his movie about Oskar Schindler, the German businessman who saved 1,200 Jews from the Nazis during World War II, THR is revisiting his film with an oral history about the miracle of its making. Speaking to those who labored to get the film onscreen — including stars Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley and Ralph Fiennes, composer John Williams, agent Michael Ovitz and Martin Scorsese, who at one point was attached to direct the picture — what follows is the most complete telling of one of the most important movies not just of Spielberg’s career, but of all time.

There has never been a more appropriate time to delve into this story. “Antisemitism always lurks in a very shallow water table,” Spielberg continues, sitting at his office at Amblin on the Universal lot, where the cards that announced the Oscar wins for Schindler’s List are framed on the wall, not far from the actual Rosebud sled from Citizen Kane. “It’s just under the ground. And every once in a while, it seeps up through the surface, into all of our lives and the news cycle, where we are publicly aware of what people are saying against Jews.”

“A Mission You Must Assign Yourself”

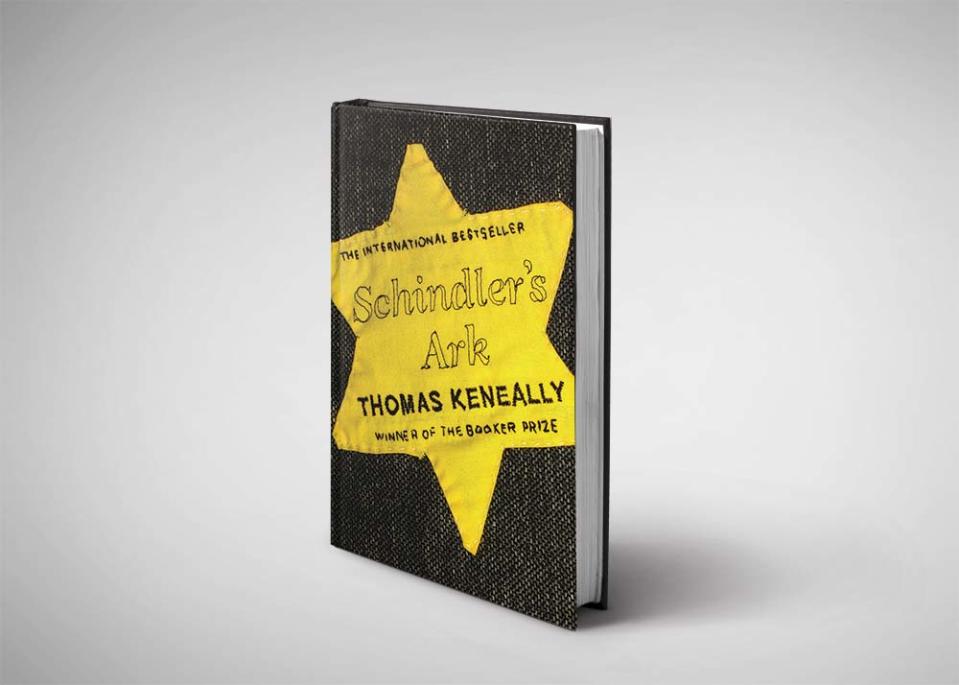

SPIELBERG In 1982, after the second week of E.T., Sid Sheinberg [president of Universal Pictures’ parent company, MCA, and Spielberg’s mentor] called to tell me about the box office, but he was less interested in that than he was with a book he’d just read the review of in The New York Times. He said, “Congratulations, sir, the second weekend is better than the first. But I want you to read a book called Schindler’s Ark. I’m sending the review over to your house.” He had a messenger on a Sunday bring the review, I read it, and I called Sid back and said, “I want to read the book.” Sid said, “I’m going to send you the book tomorrow,” and he did. A week later, Sid called and said, “Universal just bought the book for you. Sir, this must be your next picture. This is a mission you must assign yourself. This story has to be told.” That began a 10-year process.

The book, published in 1982 in England and Australia as Schindler’s Ark and later that year in the U.S. as Schindler’s List, was penned by the Australian author Thomas Keneally after he encountered one of the Jews rescued by Schindler, Leopold Page, in Beverly Hills, where Page had opened a leather goods shop after the war. Page, incidentally, had years earlier pitched the story of his rescuer to Hollywood; in 1963, Casablanca co-writer Howard Koch penned a script based on Page’s story for MGM, and Sean Connery was approached about starring, but that version never panned out.

SPIELBERG I wasn’t sure if I could get a script developed from the book. The book didn’t have a narrative that was obvious to the naked eye. It was full of names, facts, dates and times — certification of authenticity. The great mystery, though, which I could never solve when I read it, was: Why did Schindler do this? Why did he risk his life and spend 95 percent of the money he’d amassed to buy his workers back from [Kraków-P?aszów concentration camp commandant] Amon G?th and eventually bring them to freedom? Every time I look at my Rosebud sled hanging on the wall, I think, “I never had the Rosebud moment for Schindler’s List that Orson Welles found for Citizen Kane.”

Spielberg commissioned several screenwriters to take a stab at an adaptation, but none of the drafts satisfied him. And he was terrified that, even if he had a suitable script, he wasn’t up to the job of bringing it to the screen.

SPIELBERG I hadn’t made what I’d call my first “adult” film, and I was terrified of Schindler’s List being my first, because what if I wasn’t mature enough? I was certain I wasn’t ready to deal with the gravitas of that subject matter, morally or cinematically, and I felt I lacked the wisdom to be able to discuss the story in the inevitable conversations that all of us have after our films are ready to be released. But I didn’t want to stop the story from getting out into the zeitgeist, so I went to Sydney Pollack. He tried and decided he wasn’t able to do it. I might’ve mentioned it to Barry Levinson at one point; I think Barry passed. And I went to Marty [Scorsese], and Marty was intrigued. It was Marty who hired Steve Zaillian, so the greatest contribution Marty made was finding the best screenwriter to adapt Keneally’s book.

“We Pulled Out Every Card We Had”

Scorsese agreed to direct Schindler’s List. Over time, though, Spielberg began to regret giving it away. For one thing, he had begun to make adult-friendly movies.

SPIELBERG I couldn’t have made Schindler’s List without The Color Purple and then Empire of the Sun. Those were my two huge stepping stones before I really took a deep breath and said, “Now I’m ready.”

He was also troubled by rising Holocaust ignorance and denialism in America and, in the wake of the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, hate abroad.

SPIELBERG I collected public school textbooks from California, New York and Chicago, and could not find any references to the Holocaust in the textbooks that were being taught. They mentioned that innocent people were killed by the Nazis. They never said they were Jews. It was alarming what was beginning to happen [overseas, as well]. The whole thing in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Sarajevo, and the term “ethnic cleansing,” that was a motivator for me in a big way.

His 1991 marriage to Kate Capshaw, who converted to Judaism ahead of their wedding, was another major factor.

SPIELBERG When I married Kate, a lot of things opened up in me. One thing was being able to embrace the impossible. It made me take risks more than I had ever taken before. And I thought that if I was going to take a risk, the greatest risk — not just to myself and my career but to the entire survivor community — was taking on Schindler’s List.

CAA’s Ovitz represented Scorsese; he didn’t represent Spielberg, but he wanted to. He says he saw an opportunity to satisfy one A-list client and sign another.

MICHAEL OVITZ (CAA co-founder/chairman) Marty was developing a lot of movies, none of which at the time I felt would have the commercial result that he needed. One of the biggest things with Marty — and I started handling him in 1979 — was that Marty never cared about money, but he had to live. One of the things I tried to do for him was get him to make not just passion projects but projects that he was passionate about that would also have wider audience appeal. Schindler’s List, in retrospect, looks like it was always going to be a well-received movie, but let me tell you, at the time it wasn’t something that a lot of people were jumping up and down about. It was such a difficult subject, and I wasn’t sure if it was going to tap a commercial vein, so I was looking for something else for Marty. While that was happening, I was talking to Steven every single day, because one, I was trying to sign him, which I did; and two, I was talking about the projects that he was doing. He was developing Cape Fear, a remake. I asked Marty to look at the original and to read the script of the remake, and he did. I then asked what he thought of it, and he said he really liked it. I said, “Would you ever consider trading Schindler’s for Cape Fear? Look, you’re not Jewish, Steven is. This is a real passion project for him. I have no idea if anyone will go see it. I’m not even sure we’ll get it set up. But Cape Fear you could do with Bobby [De Niro],” who was also my client, “and it’s a movie that would attract an audience.” Through a period of weeks and a lot of conversations between me and Steven, me and Marty, and Marty and Steven, we agreed on a swap: Steven would give Marty Cape Fear and executive produce it, which would help from the standpoint of audience appeal; and Marty would give Steven all the work he did on Schindler’s, plus the underlying rights. We closed that deal verbally, all shook hands, and then the hard part began.

The filmmakers recall it somewhat differently.

SPIELBERG I would never have done that. Marty would never have done that. There was never a trade.

MARTIN SCORSESE I’d just come off [directing the 1988 film] The Last Temptation of Christ. There was a lot of controversy and difficulty, and a lot of blame was put on the Jewish community, which totally threw me. I was very sensitive to the reactions. With the Catholic one [Last Temptation], I could argue; with other groups, I had to be very careful. I’d asked Steven Zaillian to come on to do the script, but by the end of it, I felt that if there was any controversy that would come up, I didn’t know if I could’ve stood my ground in terms of who the man [Schindler] was. I didn’t want to do more harm to the Jewish community. I knew it was Steve’s passion project for many years. So I gave it back.

OVITZ Marty did Cape Fear, and it turned out to be a huge hit. He made some money.

SCORSESE Cape Fear was payback. The payback at that time was for Last Temptation. I had a deal at Universal. They allowed Last Temptation to happen, so I helped them with the Schindler thing and I did Cape Fear and Casino. As Mike Ovitz told me, “They’ll get this picture [Last Temptation] made for you, but they’re going to want that pound of flesh. So I gave them flesh — I lost some weight. (Laughs.)

Spielberg and Zaillian took a research trip together.

SPIELBERG I said, “Let’s go to Auschwitz” — I had never been — “and let’s go to Poland. Let’s visit all the locations that Thomas Keneally researched.” So we flew to Poland and spent time at the site of the P?aszów forced-labor camp. We went to Schindler’s actual apartment. And we went to Auschwitz, which was the most impactful experience I’d ever had up to that point in my life. Then we got back on the plane and I said to Steve, who had written a 105-page screenplay for Marty, “This has to be a 175-page script. I don’t care how long the film is. You brilliantly scratched the surface, and you’ve solved some major issues in bringing a narrative to the story, but we have to go deep with it.”

Around then, another Ovitz client, Michael Crichton, wrote Jurassic Park. Ovitz says he offered the film rights, with Spielberg attached as director, to Universal — and also began to nudge the studio about Schindler’s List.

OVITZ I got this crazy idea that I should attach Schindler’s List to the Jurassic Park deal, but I really couldn’t make it a “condition” of the deal. This is where it got really sticky and delicate. I called Sid, and so did Steven. And we said, “Look, we’ve got this movie, Schindler’s List. It’s about the Holocaust. It’s going to be tough. It’s going to be real. Steven wants to make it.”

SPIELBERG I never had to convince Sid to greenlight Schindler’s List, since it was Sid who gave me the book 10 years before and insisted that I direct it as soon as possible.

Spielberg completed principal photography on Jurassic Park and hoped to begin making Schindler’s List immediately.

SPIELBERG Tom Pollock, who was running the feature division of Universal, said, “I think it’s great that you’re interested in doing Schindler’s List, but you’ve got to finish Jurassic Park first.” I was in post on Jurassic Park. I said, “I think I can overlap. I can do Schindler’s List while I’m finishing Jurassic Park.” Tom resisted that. He said, “Jurassic Park is a huge piece of business for this company; you can’t abandon it.” I said, “Tom, I’m not going to abandon it. I’ve locked the film. All I have left to do is mix it, score it and correct the color.” And he said, “Well, you can’t do that from Eastern Europe.” And I said, “Yes I can.”

Pollock acquiesced. Spielberg planned to edit Jurassic Park from Europe, but privately sought stateside help with its sound mixing. His solution has never previously been reported.

SPIELBERG I called George [Lucas, Spielberg’s longtime friend and occasional collaborator]. I said, “George, I’m in trouble. The studio’s really upset with me that I’m going to not mix Jurassic Park and go off to Europe and make Schindler’s List. Would you mix Jurassic Park?” I already had his mixers working on the film, so George said he’d take over. And he and Kathy Kennedy mixed the film.

Then came another battle with Pollock.

SPIELBERG Tom found out that I’d decided to shoot the film in black-and-white. He was really upset about that. He called me and said, “It’s a challenging piece of business by itself. The subject matter alone doesn’t guarantee any return” because they had agreed to put up $20 million to make the film. “But if you make it in black-and-white, it’s going to give us no chance to be able to recoup our investment.” I said, “If I make it in color, it’s going to do what shooting Color Purple in color did to Color Purple.” Color Purple should’ve been in black-and-white. I was accused of beautifying Color Purple because it had such a bright palette for such a dark subject. I said, “Except for George Stevens’ footage of the liberation of Dachau, everything that anyone’s ever been exposed to about the Shoah has been in black-and-white. I will not colorize the Holocaust.” He said, “Well, why don’t you shoot the film in color, you can release it in black-and-white, but we will sell the cassettes in color?”

OVITZ You couldn’t sell a black-and-white video cassette if your life depended on it. It wasn’t doable. No one had ever done it.

SPIELBERG And I said, “No, it’s a black-and-white movie.”

OVITZ I called Sid, and Sid said, “Absolutely not. There’s no chance.” After two or three weeks of probably the most difficult discussions I’d ever had as an agent, we leveraged them into saying yes. We were really rough when we did it. I will not say we handled it gingerly. We pulled out every card we had in the CAA playbook.

With the project a go, Spielberg refused to take a salary.

SPIELBERG I considered it to be blood money.

“That’s Him”

Spielberg wound up with two fellow producers on the film.

SPIELBERG Branko Lustig came to my office and pitched my other producer, Jerry Molen, on his qualifications by rolling up his sleeve and showing his Auschwitz numbers tattooed on his forearm.

Spielberg began casting 126 speaking parts, nearly all with European actors.

CAROLINE GOODALL (Emilie Schindler) Steven really didn’t want American actors playing these roles, because he felt that European actors had a visceral understanding of the second World War.

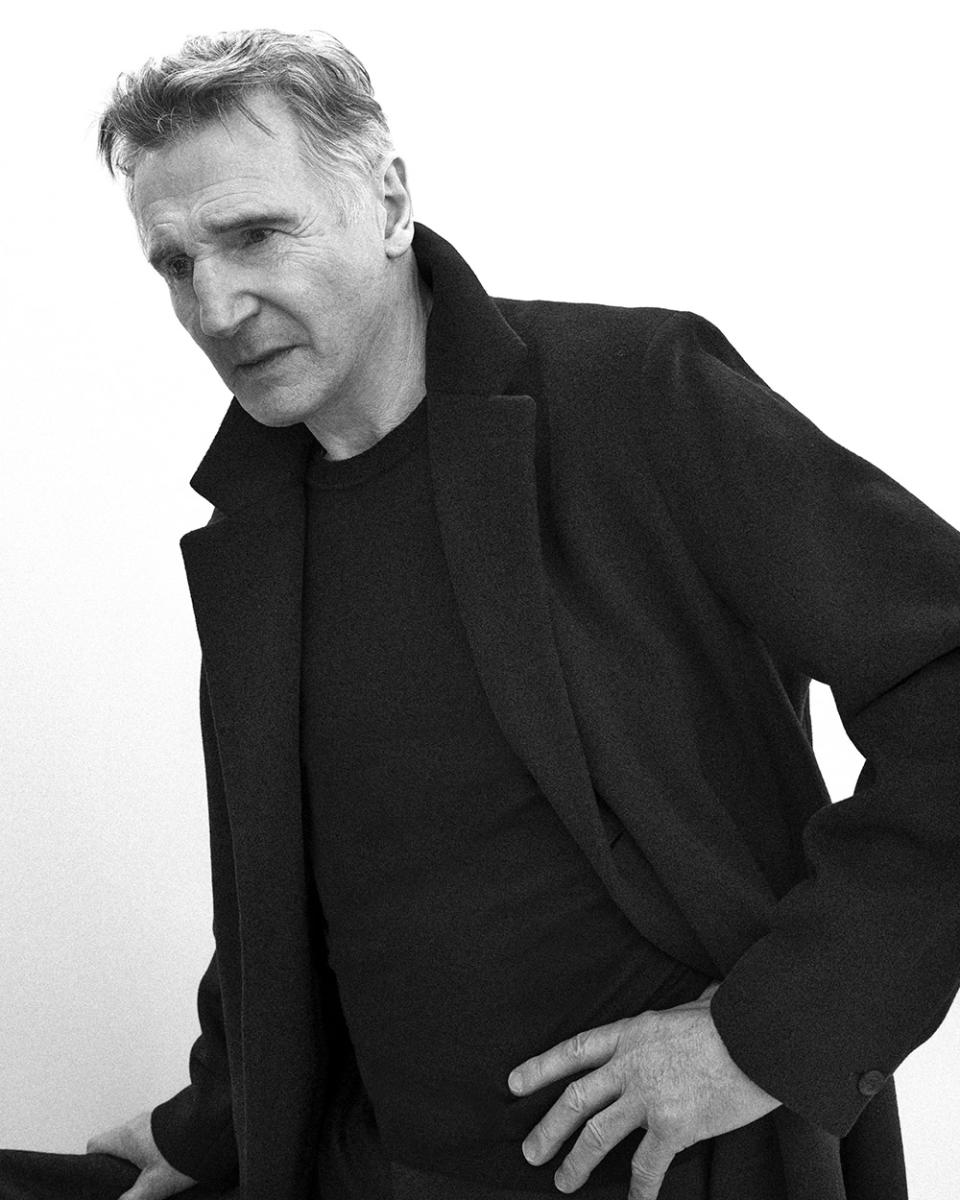

For Oskar Schindler, numerous A-listers were put forward, but Spielberg zeroed in on Liam Neeson, an Irishman who’d read for the part of Dr. Rawlins in Empire of the Sun and then offered to read opposite young actors being considering for the part that Christian Bale eventually played.

LIAM NEESON (Oskar Schindler) It was a full day. Afterwards, we were chatting and Steven said, “You should get yourself out to L.A. We need people your age and your type.” And I was like, “Oh, OK, that’s great to hear.”

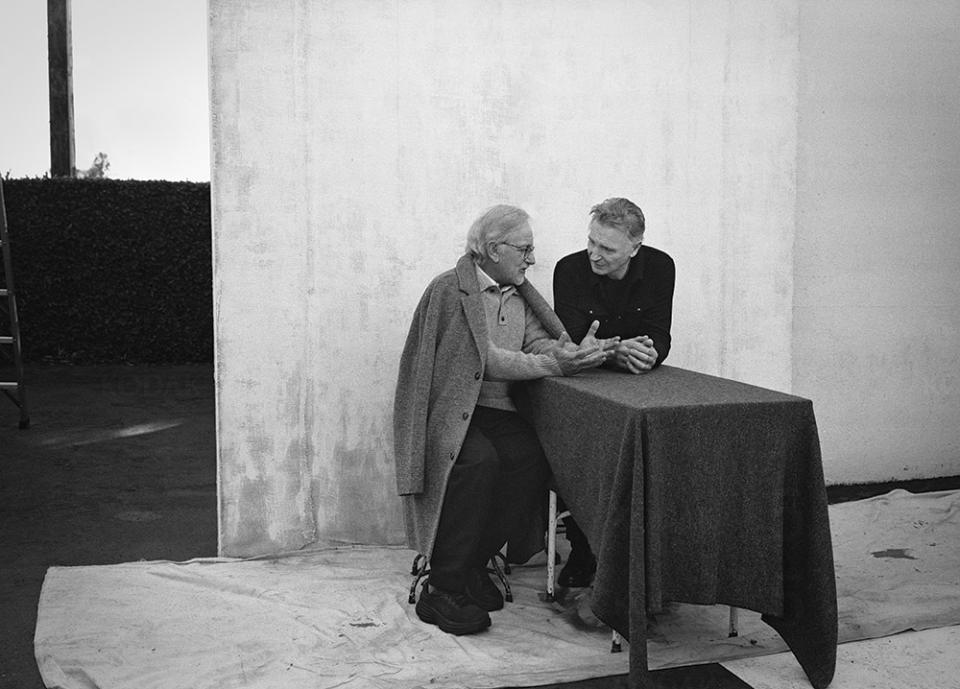

In early 1993, Spielberg, his wife, Kate Capshaw, and his mother-in-law went to see Neeson on Broadway in Anna Christie.

SPIELBERG After the show, we went to meet him backstage. Kate’s mom, who was uncensored, looked at Liam and almost burst into tears. She just adored him in that performance.

LIAM NEESON I gave her a big hug.

SPIELBERG Kate kept elbowing me in the side. “That’s him! That’s him!”

NEESON The mythological story is, Kate said to Steven when they were driving home, “That’s just what Schindler would have done, was give my mother a hug!”

Neeson tested for the part — and then there was radio silence. Rumors abounded about who else Spielberg was considering.

NEESON I heard Harrison Ford’s name. Costner’s name. The Australian actor Jack Thompson — I thought, “Oh, yeah, Jack looks very like Schindler.” I looked nothing like Schindler. Anyway, it was always in the back of my head, but I wasn’t holding out huge hope.

SPIELBERG A lot of people were interested in playing Schindler, and a lot of them were movie stars, and to all of them I promised never to divulge any of their history with me, so I’m not saying those names are accurate. I’m saying there were a number of people, even more than the names you gave me.

OVITZ Mel Gibson’s name came up. He was interested. His agent put him forward. But it wasn’t going to happen. Steven wanted a non-movie star for the part.

Spielberg eventually offered Neeson the job, and urged him to model his performance on the Time Warner CEO Steve Ross, a close friend who died in late 1992.

SPIELBERG I met Steve in 1981. He was one of the most charismatic people I’d ever met, and he wasn’t in front of the camera; he was behind a huge corporation. I had always imagined, as I was developing Schindler’s List over the next 10 years, that if Steve Ross was an actor, he’d play Schindler. So when I cast Liam, I said, “Liam, I want to show you videos I’ve taken of Steve. Look at the way he walks, look at the way he holds the room, look at how at ease he makes people who are intimidated at first sight — a minute later, they’re relaxed in his presence.” And the first thing I did was pad Liam’s shoulders, so he could have Steve’s shoulders.

NEESON I started getting a little bit confused because I’d think, “Who am I playing here? Am I supposed to be playing Steve Ross or Oskar Schindler?” Because I was also watching a couple of documentaries on Schindler. But the videos did help, I must admit.

Neeson, while finishing his play’s Broadway run, knew he had other work to do, too.

NEESON Tim Monich is an extraordinary dialect coach. I was able to work with Tim for several sessions, and he taped some stuff for me that I could listen to, to work on a general kind of Sudetenland accent. Steven also said I had to gain a bit of weight, so when I heard that, Natasha [Richardson, the late actress who was his wife] and I went to Joe Allen every night to get their famous chicken wings. And I was drinking in those days, so I kind of increased the Guinness intake, all for the sake of art.

Spielberg, meanwhile, faced a logistical challenge.

SPIELBERG The World Jewish Congress wouldn’t let us shoot inside Auschwitz because we were a dramatic narrative, and they had a policy that only documentaries could shoot at Auschwitz. I didn’t know what to do. Edgar Bronfman Sr. introduced me to the president of the World Jewish Congress, and I came up with an idea there at lunch. I said, “Would you object to me shooting outside the grounds of Auschwitz?” He said, “No.” I said, “What if I use the gatehouse” — the infamous gatehouse of Auschwitz — “and build the barracks just outside Auschwitz? If you’d let me back the train into Auschwitz, and then the train exits the gatehouse, it will appear as if it’s entering Auschwitz because you’ll see barracks on both sides.” He looked up at the ceiling, took a couple of breaths and said, “Yes, I could accommodate that.”

Then came a call from Billy Wilder.

SPIELBERG That was a sad story. I had known Billy because when I was making E.T. and Poltergeist at MGM, Billy was a consultant there. He was given scripts to read, especially comedies, and would make notes on the scripts and give them back to the studio people. Billy felt he was wasting his life. We would have lunch often in the commissary, and Billy would say, “I just cannot get a film off the ground anymore. Whatever worked for me for 30 years is not working any more. The humor is different. I read these scripts, make some notes, give ideas, and my ideas are ideas that would’ve been brilliant in the 1940s and ’50s, but nobody’s accepting them today.” Years later, he called me at the office and said, “I need to see you, it’s very important.” I said, “OK, I’ll come over to your house.” He said, “No, I need to come to you, because I’m going to ask you for something.” So he came over to Amblin and up to my office, and he said, “I just read a book and found out you own it, Schindler’s List. This is my experience before I came to America. I lost everyone over there. I need to tell this story, and I hear you own the rights. Will you let me direct this and you can produce it with me?” And I didn’t know what to say except to tell him the truth. I said, “Billy, I’m leaving for Krakow in three weeks. The whole film’s been cast. All the crew’s been hired. I start shooting at the end of February.” Billy couldn’t speak, and then I couldn’t speak, and I just reached my hand out and Billy took my hand.

Now it was time for everyone to head to Poland.

NEESON We finished the play on a Sunday afternoon. The next morning, I was flying out to Kraków. And then the morning after that, I was at the gates of Auschwitz.

“De-Hollywood-ize My Own Intuition”

Production centered in the Polish city of Kraków, which everyone remembers as freezing and bleak. Throughout the 72-day shoot, which began on March 1 and ran into June, the cast and crew stayed at the Hotel Orbis Forum.

GOODALL Kraków was just coming out of the Cold War — it was still in the Cold War! Everything was gray, covered in snow and freezing. And we were in this Soviet-era, brown-on-brown, very basic hotel. But everyone was in it except for Steven, so that was great.

EMBETH DAVIDTZ (Helen Hirsch) There was a really weird little bar downstairs where you’d have a drink when you got home from work, and then everyone would go to their little post-communism square room.

Spielberg stayed nearby.

SPIELBERG We rented a house that was KGB headquarters before the wall came down. It was a very secure blockhouse with about seven rooms that we turned into bedrooms. It was surrounded by a big fence on about an acre and a half of property, always snowed in, and six of my seven kids were there, sometimes all seven.

OVITZ They set up satellites and all kinds of tech equipment that no one knew existed so that Steven could edit at night.

MICHAEL KAHN (film editor) He put a sign out front that said, “Hotel Kalifornia,” and I had an editing room in there.

Filmmaking got underway.

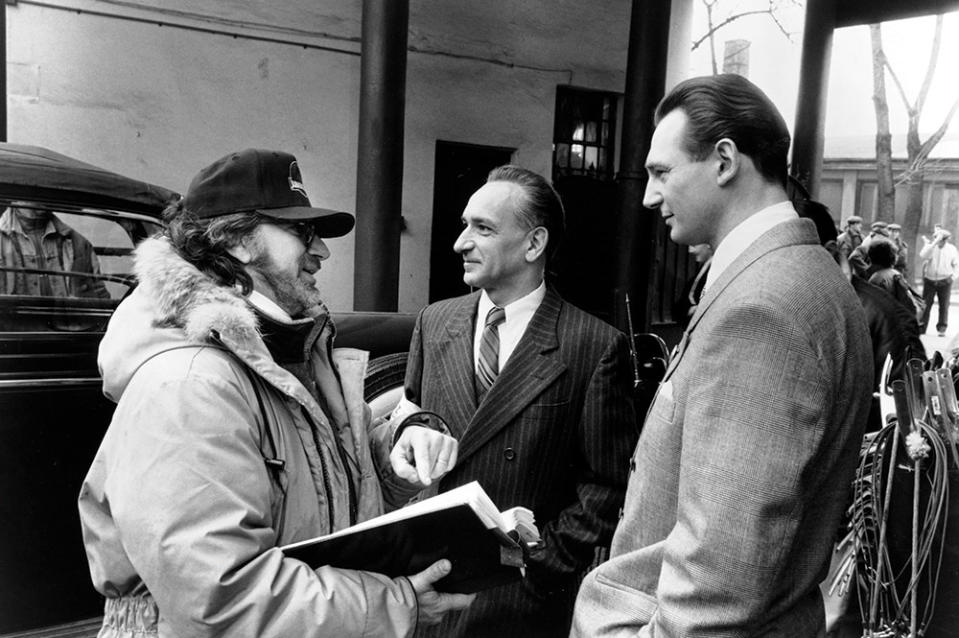

NEESON Steven was moving at such a fast pace. His energy was phenomenal. This was the first time, he told us, that he’d directed without a storyboard.

SPIELBERG The thought process was to de-Hollywood-ize my own intuition, my fallback safety net, which is to do a bunch of fancy shots. I left the crane at home. I even left the playback machine at home. I wanted to be as analog as possible.

GOODALL He was doing 48 setups a day! We had two or three cameras at a time. He was like, on fire.

RALPH FIENNES (Amon G?th) I remember Ben Kingsley saying, “He’s putting the camera in all the right places.”

STEVE BAUERFEIND (Spielberg’s 25-year-old production assistant) Steven would say, “Let me have a camera,” and he would put the camera on his shoulder and go in the middle of the action.

FIENNES I’ve worked with quite a few directors since, and none of them have had that kind of excitement about making a film. Steven gave me wonderful ideas. A lot of the things that I did that people commented on were ideas of his, like taking the cigarette off the parapet before I shoot the gun.

OVITZ I will never forget going to the set of Schindler’s List, and having dinner with Steven and Kate, and Steven having to excuse himself to go edit after he’d shot an entire day.

The gravity of the subject matter hit at unexpected moments.

NEESON Before my first scene, we were at the gates of Auschwitz. I was walking outside the barbed wire, waiting to be called to set. I had my Schindler stuff on, a big fur-lined coat, and I was a little nervous, looking at the huts inside Auschwitz. Branko sidled up beside me and said, “How do you feel?” I said, “I feel OK. It’s an intense scene, and it’ll be good to get it under my belt.” Branko casually pointed to a hut and said, “See that hut there, second from the left?” I said, “Yeah.” He said, “That’s where I was.” Fuck, I just lost it. He was there at the age of 6. Two years he spent there. I remember my knees weakened, and I thought, “You’ve got to pull yourself together, man. This isn’t acting in just another movie.”

BAUERFEIND There were many survivors that found out we were doing the movie, so they would come to Kraków and find out where we were shooting. I remember so many times somebody from production would come up and tell one of Steven’s assistants that there was a woman there who was one of Schindler’s survivors, or who had lived in Kraków, and he would always go and talk to them, these cute little old ladies [the first being Niusia Horowitz, who had been saved by Schindler] telling the story of some experience they’d had. I remember one was about how people, when they were in the camps, in order to be able to keep gold as a currency, would pull out their fillings, put them in bread and eat it, and would just keep recirculating the gold so that they could have it as currency to trade. The script would evolve during filming because he’d be like, “I heard this incredible story …”

To many, the film’s most stunning sequence, up there with the opening of Saving Private Ryan in the Spielberg pantheon, is the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto, which runs for 15 minutes and was shot entirely with handheld cameras and which includes a flash of color: a little girl in a red coat.

SPIELBERG Keneally wrote about that in the book. I thought it meant much more than just an observation by Oskar. For me, it was like waving a red flag at a world that, because of their own antisemitism, refused to pay much attention to the Holocaust, including Roosevelt, Churchill and Eisenhower, who knew about the death camps because word had come down from the World Jewish Council. It was as obvious as a little girl in red.

Some on the film encountered antisemitism in Poland, even a half century after the war.

BEN KINGSLEY (Itzhak Stern) I can describe it as a low, sinister hum, like a piece of music, running through all our days, this base note of hatred.

DAVIDTZ I walked into a store with Janusz [Kamiński, the film’s Poland-born cinematographer] and was speaking English, so this woman there probably knew we were there for the movie, and she became really aggressive and animated. I left. I remember Janusz, who is very frank, saying, “Fucking Poles, man. They’re just antisemitic.”

NEESON I heard my own driver talking in a not very nice way about Branko Lustig. It was just a throwaway comment about their salary or something. He mumbled to himself something like, “Well, of course, he’s a Jew.”

FIENNES I was getting ready to do a scene. I was standing, not shooting, but I had my S.S. uniform and coat on, and a little Polish lady came up and said something, smiling. I had at that time befriended a lady called Batia [Grafka], who was the head of props and was Polish. This woman said something, and Batia’s face clouded over. I said, “What did she say?” Batia said, “She said, ‘The Germans weren’t such bad people.’”

KINGSLEY One day we were relaxing in the bar of the hotel, and a Polish man approached one of my fellow actors [Michael Schneider] and asked if he was a Jew. Quite openly, my fellow actor said, “Yes.” This hotel guest mimed a noose around his neck, which he then pulled tight. My fellow actor broke down in tears. I was very upset, and I asked this person to leave in no uncertain terms.

The shoot took a heavy toll on Spielberg.

SPIELBERG The hard days were beyond my imagination, and the easy days were never easy. Everything we shot at Auschwitz with the women, when the women’s train was reassigned to Auschwitz, that was the toughest.

NEESON Steven, very sweetly, always shared his vulnerability, which I loved in him.

SPIELBERG Often I was a basket case, just a wreck, and Kate always sat with me, let me get it out and talked me through it, or just let me be quiet and she would be quiet. We’d sit there and look at each other. Emotionally, it was the hardest thing I’ve ever done as a filmmaker.

Mid-shoot, Spielberg’s spirits were lifted at a Passover Seder that he hosted at the Hotel Forum.

SPIELBERG All of a sudden, all the German and Austrian actors that were playing the Nazis came in, put on yarmulkes and sat down next to the Israeli actors, who shared Haggadahs with the actors who were playing their oppressors. I sat at the head of the table and couldn’t contain myself. It was one of the most extraordinary, beautiful things I’d ever witnessed.

Additionally, Spielberg’s friend Robin Williams helped.

SPIELBERG Robin knew how hard it was for me on the movie, and once a week, every Friday, he’d call me on the phone and do comedy for me. Whether it was after 10 minutes or 20 minutes, when he heard me give the biggest laugh, he’d hang up on me.

NEESON Steven would tell us afterward the sorts of things Robin would say. Once he started a riff of “I’m not a Nazi, I’m a nutsy,” all this sort of shit.

Toward the end of the shoot, Spielberg had an idea for a new ending.

SPIELBERG We were about three weeks from wrapping, and what was keeping me up at night was: Was my movie strong enough? I always edit as I shoot, so I see scenes cut together, and I knew what I had — I thought at that point that it was the best work I’d ever done as a filmmaker. I rarely say that about myself, but I said it about that film because it was apparent to me that I’d never done anything like this before, and I was so proud of the work. But who would believe the story? Who would believe that this really happened? Would this story just feed more Holocaust-denying? In order to ensure that people would know that this wasn’t dreamt up by the guy that made E.T. and Raiders and Jaws and Close Encounters — I had all those films working against me, in a way, taking on the Shoah — I needed to come up with something that would verify the story I was telling. I said to Branko, “Can we get as many of the Jews that Schindler saved as possible to come to Jerusalem? They can line up and go past Schindler’s grave and put commemorative stones on the grave. What I would do is get the people whose story we’re telling and put the castmember next to the actual person.”

One hundred twenty-eight Schindlerjuden — and Emilie Schindler and Sophie Stern, widows of Oskar and Itzhak, respectively — were flown to Israel.

NEESON Steven had originally wanted Ben and myself to dress up as our characters. I begged him not to. “Please, Steven, please.” I just felt that would be kind of insulting to the Schindlerjuden. Anyway, he scrapped that idea. These lovely people arrived. And we had a fucking party — the wine, the whiskey, I’d never seen such joyous celebrating!

DAVIDTZ We went to this reception downstairs where all these amazing people were. I met Helen Hirsch, who was this tiny firecracker. They had translators, and everyone was paired up with their person. I remember this very lively, alive group of people. I, of course, wanted to ask the deep questions. They didn’t want to talk about it.

Mrs. Schindler arrived from Argentina, where she had fled with Schindler after the war, and where he later left her.

GOODALL She said, “I’ve never been to Israel. And I’ve never seen his grave.” To suddenly be confronted by your husband’s grave must have been enormous for her.

The next day, everyone headed to the Mount Zion Roman Catholic Franciscan Cemetery.

GOODALL Emilie had actually been walking the night before, but she was in a wheelchair the next day. I rather feel it was because she’d had a few! It was very stony, pushing that wheelchair. My fear the whole time was that it would go over something and she’d take a tumble.

With filming completed, Spielberg headed to the Hamptons for postproduction. There, in mid-June, he learned that Jurassic Park had had the biggest box office opening weekend of all time. And there, he showed Schindler’s List to his go-to composer.

JOHN WILLIAMS (composer) When it ended, I couldn’t speak, it was such a jolt. The lights went on and I stood up, left the room and walked around outside for a few minutes, reflecting on what I’d seen. I came back in and said to Steven, “Steven, you need a better composer than I am for this film.” And he said to me, “I know, but they’re all dead.”

Williams got to work.

WILLIAMS I went right off from our meeting there to Tanglewood to do my summer concerts, and I started working at the piano on Schindler’s List. Steven and Kate came up, and I played them what I’d written, and they chose the theme that we all know. The music is very simple, which I think we all agreed it needed to be. It needed to almost sound like an old friend, like an old grieving compatriot.

“Spielberg Was My Second Schindler”

The film’s world premiere took place Nov. 30 in Washington, D.C., at the new U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

BRUCE FELDMAN (Universal Pictures senior vp marketing/Oscar campaigner) Everybody was there: President and Mrs. Clinton, all kinds of congresspeople, celebrities. It was a big night.

OVITZ It was swarming with Secret Service.

FIENNES I can remember, “All stand for the president of the United States!”

The next morning, President Clinton said of Schindler’s List, “I implore every one of you to go see it. It is an astonishing thing.” Then the L.A. premiere, a benefit for the Schindler Foundation, took place Dec. 9 at the Simon Wiesenthal Center.

SPIELBERG The most remarkable thing for me was after the credits rolled, nobody moved, left their seat, talked to each other, stood up to start milling around, looked to see where I was sitting. They sat there for a long time, not moving.

Critics raved, including Siskel and Ebert (both chose it as 1993’s best), Variety’s Todd McCarthy (“the film to win over Spielberg skeptics”) and The New York Times’ Janet Maslin (“Spielberg has made sure that neither he nor the Holocaust will ever be thought of in the same way again. … You can be sure this is not the last time the words ‘Oscar’ and ‘Schindler’ will be heard together”).

MARVIN LEVY (Spielberg’s personal publicist) At the official Academy screening, so many people showed up that they had to also use an extra theater, and I don’t know if that accommodated everyone.

Filmmakers reacted similarly. Scorsese said, “I admired the film greatly.” Roman Polanski declared, “I certainly wouldn’t have done as good a job as Spielberg.” And Wilder gushed, “They got the best. They couldn’t have gotten a better man. The movie is absolutely perfection.”

But would the public buy tickets? Even though prior to its release Spielberg had directed four of the top 10 box office hits of all time (Jurassic Park, E.T., Jaws and Raiders), projections had Schindler’s List making just $25 million. Of course, those turned out to be wildly off; it ultimately grossed $322 million worldwide. Among those most moved by it were Holocaust survivors.

ANNETTE INSDORF (Columbia University film professor/author of Indelible Shadows: Film and the Holocaust) It validated and valorized them. Spielberg brought Holocaust remembrance into popular culture and gave people like my own mother, who survived Auschwitz, an implicit invitation to talk about what they experienced and witnessed.

CELINA BINIAZ (92-year-old Holocaust survivor) Schindler gave me a life, because by putting me on the list with my parents, he saved me. I was liberated by the Russian Army on the 9th of May, 1945, from the Schindler factory, which was part of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp. I was the youngest female on what is now known as “the list” — I was only 13 — and for 40 years after, I never spoke about it. I lived in a community on Long Island, and nobody there knew of my Holocaust experiences. It was only with the introduction of the film that I spoke. I can’t tell you what an impact that film has had on my life. I always say that Steven Spielberg was my second Schindler. He gave me a voice.

“Manna From Academy Voters”

Schindler’s List was the clear frontrunner for numerous Oscars, but nothing is certain until envelopes are opened.

FELDMAN When people ask me, “What was your approach to the campaign?”, my response is, “Don’t fuck it up.” That meant, “Don’t be too aggressive. Make sure whatever you do is appropriate, smart, well thought-out.” The campaign was trade ads, screenings and conventional publicity. It was long before the days of Q&As and screenings in Aspen. We didn’t have lavish parties and luncheons at Spago. There was no internet or social media.

Even 30 years ago, though, it was common to send voters screeners, in those days on VHS.

SPIELBERG I stopped that. They said, “You could lose the Oscar.” I said, “I’m probably not going to win, anyway.” And the studio said, “But we’d like to win.” I wouldn’t let them. I said, “Please do not send out screeners. I want this film to be seen in the company of strangers. I want people to go into movie theaters and sit there with people they don’t know and share this experience communally. It’s not asking a lot.”

Instead, an elegant booklet was mailed to Academy members.

FELDMAN Steven had hired David James to be the unit photographer. He was a top figure in set photography, and he took lots of pictures that were very atmospheric — dark settings, smoke curling up from a cigarette, the sky looking really great. So we had all this incredible artwork to work with. My feeling was, “Why don’t we just let the picture sell itself? Just show them these pictures. Don’t put any quotes or braggadocio.” We didn’t need to say “For your consideration.” Everyone knew what it was.

On Feb. 9, 1994, the Oscar nominations were announced. Schindler’s List landed a field-leading 12. Harvey Weinstein, whose Miramax was distributing Jane Campion’s Palme d’Or winner, The Piano, which received eight Oscar noms, including best picture, began mounting an aggressive challenge. He ran as many as seven ads a day in the trades.

SPIELBERG We weren’t doing that with Schindler’s List. We were holding back. Universal wanted to hold back. They didn’t want to chase Harvey Weinstein.

OVITZ The agency was fighting Harvey Weinstein tooth and nail. We wanted Steven to win. Harvey was just relentless on Academy campaigns, because he made these movies that didn’t have big commercial appeal, and the Academy Awards — this was kind of folklore — allegedly added $10 million to $20 million of box office to a movie.

Weinstein, full of bluster, told The Wall Street Journal he thought “a major upset” was possible, and the Los Angeles Times, “I keep hearing that Chariots of Fire music,” referencing a famous Oscar upset.

CYNTHIA SWARTZ (Miramax senior vp special projects/Oscar campaigner) If you think that I spent a second thinking that The Piano could beat Schindler’s List, you’ve got to be crazy. It was ridiculous.

The 66th Oscars took place at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on March 21, 1994.

SPIELBERG I never expected to win because I’d never won an Oscar. I thought, “Why should this night be different than every other night? Because it’s a good movie and people are loving it? People loved E.T., and I didn’t win for that. The Color Purple had the most nominations of any film that didn’t win any. And just on and on. I always privately, with friends, said, “I’m going to be like Sidney Lumet and Alfred Hitchcock [who never won competitive Oscars], I’m not going to be like William Wyler or John Ford [who won multiple]. I’m not going to win an Oscar. But it’s OK.”

Most associated with the film watched from a party at Amblin.

BAUERFEIND They set up a big screen in the courtyard. I think we had a costume party to celebrate the movies that were up or something. I drank a lot. They were managing expectations for what was going to happen after what happened with The Color Purple. It was just going to be a fun party to celebrate that the film was nominated — and then it became the most fun party when the film kept winning.

The film’s nominees, of course, were at the ceremony, which was hosted, for the first time, by Spielberg’s Color Purple star Whoopi Goldberg.

SPIELBERG Whoopi’s always been my good-luck charm. When she came out to host, that was the one time I said, “Oh, shit, we could win.”

Some associated with Schindler’s List came up short, including best actor nominee Neeson and best supporting actor nominee Fiennes. But the film had won five Oscars heading into the final two categories. Best director was presented by Clint Eastwood.

SPIELBERG Clint, since Play Misty for Me, has been one of my closest friends. He comes out and he says, “Big surprise!” And I thought, “Oh, my God.”

But the winner was Spielberg, who began his speech: “I have friends who have won this before, but — I swear — I have never held one before.”

BINIAZ It literally brought tears to my eyes when he won the award — not the film, Steven.

OVITZ They finally took him seriously.

WILLIAMS I think it meant everything to Steven. He’d proven himself since childhood almost to be a masterful filmmaker.

SPIELBERG Standing up there and looking at everybody, who were standing when I got up to accept my first Oscar, I was so filled up. I was just overflowing with so many different feelings. Even looking back, I can’t break down what all of them were, but I felt vindication and deep pride. My wife and mom were sitting next to each other. I looked right into their eyes and said to myself, “OK, if you start to cry, bite your tongue. You may bleed, but you cannot cry.”

Spielberg walked into the wings and was asked to wait there because the next category was best picture, presented by his friend and frequent collaborator Harrison Ford. Ford opened the envelope and read, “Schindler’s List.” It was the first film about the Holocaust — and the first black-and-white film since The Apartment 33 years earlier — to win the top Oscar. Spielberg, flanked by Lustig and Molen, declared from the podium: “This is the best drink of water after the longest drought in my life.”

SPIELBERG I’d always wanted to win the Academy Award, and I never had, so it had been a bit of a feeling of being in the desert. I did feel like it was a dry spell, and suddenly it rained manna from heaven — manna from Academy voters! (Laughs.)

The rest of Spielberg’s speech was devoted to urging people to listen to the then-350,000 living Holocaust survivors and to teach the Holocaust in schools.

Then, celebrations began at the Governors Ball, went late into the night — and continued the next morning.

BAUERFEIND We all got to work early and lined up on the main driveway of Amblin. When Steven drove in, everyone was outside clapping and cheering for him. It was a really cool moment.

“The Best Movie I’ve Ever Made”

Spielberg didn’t direct again for three years. He was recovering from Schindler’s List and launching both DreamWorks and the Shoah Foundation. The latter recorded some 53,000 testimonies of Holocaust survivors.

KRISTIE MACOSKO KRIEGER (producer) Steven did not set out to change the world, but I think he did.

Since Schindler’s List, there’s been an explosion of films about the Holocaust — among them, Life Is Beautiful, The Pianist, Son of Saul and current best picture Oscar nominee The Zone of Interest.

SPIELBERG The Zone of Interest is the best Holocaust movie I’ve witnessed since my own. It’s doing a lot of good work in raising awareness, especially about the banality of evil.

But antisemitism and Holocaust denialism rage on.

ROBERT WILLIAMS (USC Shoah Foundation executive director) The largest set of recent testimonies that we’ve taken have been from Israel. We’ve been taking testimony of survivors of the Oct. 7 attacks. We have more than 360 of those.

BINIAZ I think, at this point, it would be really interesting to rerelease the film. For all these Holocaust deniers, for the people who say it couldn’t have happened, yes, it did, and maybe to see it again would be important.

SPIELBERG Since 2016, antisemitism has joined racism, xenophobia, homophobia and all these maladies and cultural afflictions in the air at eye level. I think it’s here to stay — and I think it’s a good thing that it’s here to stay. Everybody wants it to go away because it’s uncomfortable to deal with it. It needs to be uncomfortable, because the only way we can find a solution to the way people treat the Jews is for it to always be part of the conversation.

Schindler’s List has been selected for the AFI and Time lists of the 100 greatest films of all time, the Vatican’s list of the 45 most important films ever and the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry.

GOODALL My kids’ history book talks about Schindler’s List, and there’s a picture in there of me. It’s quite an honor, isn’t it?

FIENNES It was an extraordinary thing to be part of, being close to that level of filmmaking, that artistry, that creative energy.

DAVIDTZ I’d give anything to go back as my grown-up self and relive a day or two there.

KINGSLEY It’s in my DNA, the experience. It’s laminated into my body. It was a sublime opportunity and a great experience.

GOODALL If that was the only thing that I’d ever done, it would have been enough.

No filmmaker has ever had a better year than Spielberg’s 1993: the biggest blockbuster of all time, to that point, and the best picture. But Schindler’s List holds a particularly special place in his heart.

SPIELBERG It’s the best movie I’ve ever made. I am not going to say it’s the best movie I ever will make. But currently, it’s the work I’m proudest of.

An abbreviated version of this story first appeared in the Feb. 21 issue of The Hollywood Reporter magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Solve the daily Crossword