Senate report on CIA torture is one step closer to disappearing

CIA Director John Brennan, Sen. Dianne Feinstein. (Photo Illustration: Yahoo News; photos: AP, Reuters)

The CIA inspector general’s office — the spy agency’s internal watchdog — has acknowledged it “mistakenly” destroyed its only copy of a mammoth Senate torture report at the same time lawyers for the Justice Department were assuring a federal judge that copies of the document were being preserved, Yahoo News has learned.

While another copy of the report exists elsewhere at the CIA, the erasure of the controversial document by the office charged with policing agency conduct has alarmed the U.S. senator who oversaw the torture investigation and reignited a behind-the-scenes battle over whether the full unabridged report should ever be released, according to multiple intelligence community sources familiar with the incident.

The deletion of the document has been portrayed by agency officials to Senate investigators as an “inadvertent” foul-up by the inspector general. In what one intelligence community source described as a series of errors straight “out of the Keystone Cops,” CIA inspector general officials deleted an uploaded computer file with the report and then accidentally destroyed a disk that also contained the document, filled with thousands of secret files about the CIA’s use of “enhanced” interrogation methods.

“It’s breathtaking that this could have happened, especially in the inspector general’s office — they’re the ones that are supposed to be providing accountability within the agency itself,” said Douglas Cox, a City University of New York School of Law professor who specializes in tracking the preservation of federal records. “It makes you wonder what was going on over there?”

The incident was privately disclosed to the Senate Intelligence Committee and the Justice Department last summer, the sources said. But the destruction of a copy of the sensitive report has never been made public. Nor was it reported to the federal judge who, at the time, was overseeing a lawsuit seeking access to the still classified document under the Freedom of Information Act, according to a review of court files in the case.

A CIA spokesman, while not publicly commenting on the circumstances of the erasure, emphasized that another unopened computer disk with the full report has been, and still is, locked in a vault at agency headquarters. “I can assure you that the CIA has retained a copy,” wrote Dean Boyd, the agency’s chief of public affairs, in an email.

The 6,700-page report, the product of years of work by the Senate Intelligence Committee, contains meticulous details, including original CIA cables and memos, on the agency’s use of waterboarding, sleep deprivation and other aggressive interrogation methods at “black site” prisons overseas. A 500-page executive summary was released in December 2014 by Democratic Sen. Dianne Feinstein, the committee’s outgoing chair. It concluded that the CIA’s interrogations were far more brutal than the agency had publicly acknowledged and produced often unreliable intelligence. The findings drew sharp dissents from Republicans on the panel and from four former CIA directors.

But the full three-volume report, which formed the basis for the executive summary, has never been released. In light of a U.S. Court of Appeals ruling last week that the document is not subject to the Freedom of Information Act, there are new questions about whether it will ever be made public, or even be preserved.

After receiving inquiries from Yahoo News, Feinstein, now the vice chair of the committee, wrote CIA Director John Brennan last Friday night asking him to “immediately” provide a new copy of the full report to the inspector general’s office.

“Your prompt response will allay my concern that this was more than an ‘accident,’” Feinstein wrote, adding that the full report includes “extensive information directly related to the IG’s ongoing oversight of the CIA.” (CIA spokesman Boyd declined to comment.)

The incident is the latest twist in the ongoing battle over the report, and comes in the midst of a charged political debate over torture. Likely Republican Party nominee Donald Trump has vowed to resume such methods — “and a lot more” — in the war against the Islamic State. “I love it, I love it,” Trump recently said, describing his views on waterboarding. “The only thing is, we should make it much tougher than waterboarding.” )

The CIA allegedly tortured two terror suspects, Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, in its secret facility in Poland. Shown here in this 2005 photo is a watchtower near the Polish intelligence school just outside of Stare Kiejkuty, Poland. (Photo: Czarek Sokolowski/AP)

Ironically in light of the inspector general’s actions, the intelligence committee’s investigation was triggered by the CIA’s admission in 2007 that it had destroyed another key piece of evidence — hours of videotapes of the waterboarding of two “high value” detainees, Abu Zubaydah and Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri.

According to a brief by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which is seeking release of the full report under the Freedom of Information Act, the document “describes widespread and horrific human rights abuses by the CIA” and details the agency’s “evasions and misrepresentations” to Congress, the courts and the public.

To ensure the document was circulated widely within the government, and to preserve it for future declassification, Feinstein, in her closing days as chair, instructed that computer disks containing the full report be sent to the CIA and its inspector general, as well as the other U.S. intelligence and law enforcement agencies. Aides said Feinstein specifically included a separate copy for the CIA inspector general because she wanted the office to undertake a full review. Her goal, as she wrote at the time, was to ensure “that the system of detention and interrogation described in this report is never repeated.”

But her successor, Republican Sen. Richard Burr of North Carolina, quickly asked for all of the disks to be returned, even threatening at one point to send a committee security officer to retrieve them. He contended the volumes are congressional records that were never intended for executive branch, much less public, distribution.

The administration, while not complying with Burr’s demand to return the disks, has essentially sided with him against releasing them to the public. Early last year, Justice lawyers instructed federal agencies to keep their copies of the document under lock and key, unopened, lest the courts treat them as government records subject to the Freedom of Information Act. Weeks later, in an effort to head off a motion for “emergency relief” by the ACLU, a Justice Department lawyer told U.S. Judge James Boasberg that no copies of the report would be returned to Congress or destroyed; the government “can assure the Court that it will preserve the status quo” until the Freedom of Information Act lawsuit was resolved, wrote Vesper Mei, a senior counsel in the Justice Department’s civil division, in a February 2015 filing.

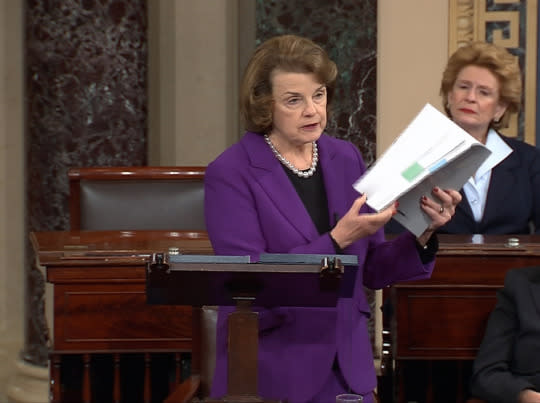

Sen. Dianne Feinstein discusses a newly released Senate Intelligence Committee report on the CIA’s antiterrorism tactics on Capitol Hill in December 2014. (Photo: Senate TV/Reuters)

But last August, a chagrined Christopher R. Sharpley, the CIA’s acting inspector general, alerted the Senate intelligence panel that his office’s copy of the report had vanished. According to sources familiar with Sharpley’s account, he explained it this way: When it received its disk, the inspector general’s office uploaded the contents onto its internal classified computer system and destroyed the disk in what Sharpley described as “the normal course of business.” Meanwhile someone in the IG office interpreted the Justice Department’s instructions not to open the file to mean it should be deleted from the server — so that both the original and the copy were gone.

At some point, it is not clear when, after being informed by CIA general counsel Caroline Krass that the Justice Department wanted all copies of the document preserved, officials in the inspector general’s office undertook a search to find its copy of the report. They discovered, “S***, we don’t have one,” said one of the sources briefed on Sharpley’s account.

Sharpley was apologetic about the destruction and promised to ask CIA director Brennan for another copy. But as of last week, he seems not to have received it; after Yahoo News began asking about the matter, he called intelligence committee staffers to ask if he could get a new copy from them.

Sharpley also told Senate committee aides he had reported the destruction of the disk to the CIA’s general counsel’s office, and Krass passed that information along to the Justice Department. But there is no record in court filings that department lawyers ever informed the judge overseeing the case that the inspector general’s office had destroyed its copy of the report.

The episode was viewed among intelligence committee aides as another embarrassment for the inspector general’s office. Months earlier, a CIA accountability board had overruled the IG’s findings that agency officials had improperly searched computers used by Senate investigators working on the report. Sharpley has been serving as acting inspector general since his predecessor, David Buckley, resigned in January 2015. The White House has yet to nominate a successor.

A Justice Department spokesman said on Friday that, since the inspector general’s office is, by statute, a “unit” of the CIA, and the agency still had its copy, “the status quo … was preserved.” But Feinstein, in a separate letter to Attorney General Loretta Lynch last Friday, took a different view: She asked that the Justice Department “notify the federal courts” involved in the Freedom of Information Act litigation about the destruction.

At issue in the ongoing legal dispute is whether the report is subject to the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA). The administration says no, and a three-judge panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals last week agreed, ruling that it is a congressional document not subject to FOIA, under the terms of a 2009 letter by which the Senate panel had received access to CIA files. The judges did write, however, that the executive branch does have “some discretion to use the full report for internal purposes.” The ACLU said on Friday it was “considering our options for appeal”; CIA spokesman Boyd said the agency’s copy of the report would be retained “pending the final result of the litigation.” But he pointedly made no mention of what would happen to the CIA’s copy of the report after that.

CIA headquarters in Langley, Va. (Photo: Charles Ommanney/Getty Images)

In the meantime, Feinstein, joined by Democratic Sen. Patrick Leahy of Vermont, has taken a different route, petitioning David S. Ferriero, the chief of the National Archives, to formally declare the report a “federal record” that must be preserved “in the public interest” under a law known as the Federal Records Act.

In a letter last month, the senators expressed concerns that federal agencies might destroy their copies of the report. “No part of the executive branch has ruled out destroying or sending back the full report to Congress after the conclusion of the current FOIA litigation,” they wrote in an April 13, 2016, letter. A similar point was raised by more than 30 advocacy groups who noted in a separate letter to Ferriero last month that the archivist had a duty to act whenever there was a threat that government records are at risk of “unauthorized destruction.”

Ferriero on April 29 wrote back to Feinstein that he would not rule on the question until the FOIA court case is concluded. And last week, Burr renewed his call to have all copies of the report sent back — presumably a way to ensure they are never publicly released. Citing the new Court of Appeals ruling, “Sen. Burr anticipates the return of these full reports to the Senate Intelligence Committee,” a spokeswoman said.