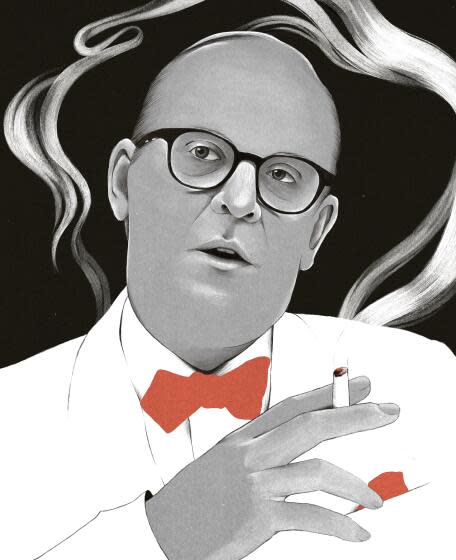

Truman Capote continues to captivate even amid his downward spiral in 'Feud: Capote vs. the Swans'

Truman Capote was an immensely public figure, even, perhaps especially, when he was self-immolating. Movies and television have offered a front-row seat to his lacerating wit and his downward spiral. Both are on display in FX limited series “Feud: Capote vs. the Swans,” courtesy of star Tom Hollander.

The Capote story is well-trodden ground. “Capote” (2005), for which Philip Seymour Hoffman earned an Oscar playing the writer, and “Infamous” (2006), starring Toby Jones, both tell the story of how Capote, at the height of his talent, essentially sold his soul to write his bestselling 1966 “nonfiction novel” ”In Cold Blood.” Falling in love with one of his subjects, murderer Perry Smith — portrayed by Clifton Collins Jr. in “Capote” and Daniel Craig in “Infamous” — then wishing for Smith’s death so he can finish the book, Capote enters a state of moral torment and, as the films suggest, post-“Blood” creative paralysis.

“Feud: Capote vs. the Swans” picks up the story some years later. Capote is now a raging alcoholic and pill popper, laboring over a book, “Answered Prayers,” that he will never finish. He spends much of his time swilling cocktails and gossiping with his “swans,” an assortment of society women including Babe Paley (Naomi Watts), Slim Keith (Diane Lane), C.Z. Guest (Chlo? Sevigny) and Lee Radziwill (Calista Flockhart). He’s playing the raconteur on talk shows, telling more stories than he writes.

Read more: Review: A glamorous squad and gossip fuel Ryan Murphy's 'Feud: Capote vs. the Swans'

Then he self-sabotages, writing a thinly disguised short story for Esquire magazine that spills the tea all over his swans, particularly Paley, his favorite of the bunch. He is quickly exiled from the kingdom, a social pariah left to his most self-destructive impulses. Plagued by liver disease and excessive drug use, he died in 1984 at age 59. (A cobbled-together version of “Answered Prayers” was posthumously published in England in 1986 and in the U.S. in 1987 to mixed reactions.)

This is the Capote that Hollander tackles in “Feud,” a prematurely over-the-hill writer drowning his gifts in booze and ostracized by the very people he put on a pedestal. It’s a Capote who, by this point, was playing a caricature of himself for public consumption. Hollander, seen most recently in the second season of “The White Lotus,” knew he had to move beyond the big-screen Capote depictions and the easily ridiculed spectacle the man himself became.

“The danger is that you become just a sort of grotesque,” Hollander said in a recent video interview from the Reading train station, outside of London. He’s carrying a geranium, which he will soon present as a housewarming present to a friend in the village of Dent. “You have to look at the real person, and then you have to rise to the occasion. You have to find moments of stillness so that the audience gets a chance to look into your eyes.”

What they see is rarely pretty. Fueled by wounded ego and gallons of vodka, the Capote of “Feud” is a far cry from the blinding literary talent who penned “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” and “In Cold Blood.” He has ingratiated himself with the swans, all obscenely wealthy, most married to powerful men (Paley was the wife of CBS chieftain and prolific philanderer William S. Paley, played here by Treat Williams). They accept Capote as a source of gossip and entertainment, a sort of court jester to trot out at dinner parties. Capote rides their coattails — until, in an act of pique, he sets them on fire in print.

“I think a little bit of him was angry at his position in that society,” Hollander said. “He would deny that fervently, repeatedly, but he was Truman Capote. He was the greatest writer of his generation, or one of them. And they treated him as one up from the staff. He was a gay man that was stuck at the other end of the table and very welcome as long as he told funny stories and scandalized everybody. He had to sing for his supper. They didn't have to sing for their supper. They just had to sit there looking good.”

Capote completists looking for depictions of the author could go back to the 1962 movie adaptation of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” with John Megna playing Dill, a character based on the writer — a childhood friend of "Mockingbird" author Harper Lee. Capote infamously played himself in “Murder by Death” (1976), the shooting of which is briefly re-created in “Feud” (it seems Capote, in an intoxicated daze, had trouble remembering his lines).

But “Capote,” “Infamous” and “Feud” form a sort of informal trilogy of ruin. “Capote” is pure tragedy. “Infamous,” covering the same material, works shades of comedy into the mix. And “Feud,” like so much under the Ryan Murphy production umbrella, is glorious melodrama, with room for ample emotional range — rage, defiance, despair — on Hollander’s part.

“Swans” creator Jon Robin Baitz found his star to be the perfect Capote.

“Tom brings tremendous improvisatory freedom, the kind that comes from instinct and intelligence — some very acute balance of emotional and investigative curiosity,” Baitz said in an email. “He is also courtly, kind and funny, and the swans swooned for him.”

As Hollander sees it, Capote took a torch to his social life for work that wasn’t even close to his own standards. The story that caused the swans to scatter, “La C?te Basque” (named for the swank New York restaurant where the author gathered with the swans), is thin gruel compared to Capote’s best writing. “He thought he was doing something better than he was,” Hollander said. “He thought he was writing an astonishing piece of social satire and, to an extent, celebrating this world. But actually, he was just writing a little bitchy scandal sheet. I don't think he was as good as he used to be because he drank so much. He wasn’t as clever as he used to be because he'd lost too many brain cells.”

And yet Capote continues to draw us in for another lascivious story and another dramatic portrayal. Forty years after his death, he still holds court.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.