‘Wise Guy: David Chase and The Sopranos’ Looks Back at the Iconic Mob Series — and the Man Who Made It

“I really regret the amount of fucking verbiage from this morning,” the man in Dr. Jennifer Melfi’s office says. “Who gives a shit, about all these personal questions?”

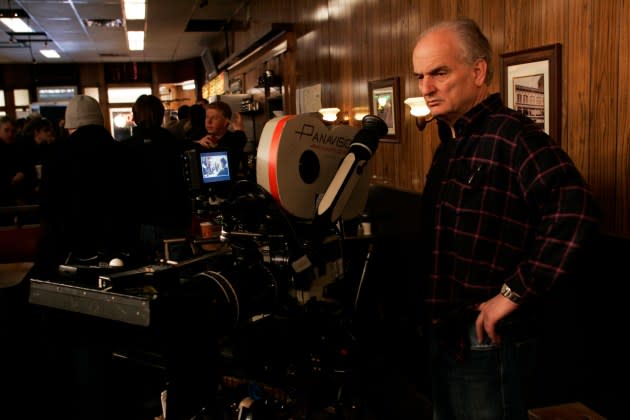

While this could easily be a quote from Dr. Melfi’s most infamous patient, New Jersey wiseguy Tony Soprano, it is in fact uttered by David Chase — the veteran TV producer who created Tony, Melfi, and every other character on the immortal series The Sopranos. When he says it, Chase is sitting in a recreation of the good doctor’s office, for an interview that provides the spine of Wise Guy: David Chase and The Sopranos, a new HBO documentary from filmmaker Alex Gibney. Throughout the two-part film, Gibney does his best to break down any barriers that exist between Chase’s life and events from the groundbreaking series he created. When Chase talks about falling in with a rough crowd as a kid, we see not only clips of Fifties and Sixties films about juvenile delinquents, but scenes of Tony and his tracksuit-clad crew moving menacingly. At one point, Gibney has Chase follow the same route from Manhattan through the Lincoln Tunnel and into Essex County, NJ, that Tony does in the Sopranos opening credits, placing Chase in the passenger seat of the car so it can be edited to appear as if he’s sitting opposite Tony.

More from Rolling Stone

Jimi Hendrix Documentary Film Coming From 'Greatest Night in Pop' Director

Bruce Springsteen Reveals 'Road Diary' Tour Documentary Heading to Streaming in October

Vince McMahon Docuseries of 'Harrowing Allegations' Gets Release Date

After a while, though, these flourishes, while entertaining, prove unnecessary. As everyone who has ever spent much time in the company of David Chase can tell you, there is an awful lot of himself in these iconic characters he crafted. Physically, there’s not a great resemblance between the modestly-built Chase (particularly now that he’s in his late seventies) and the colossus that was the late, great actor James Gandolfini. But the more you listen to the writer talk, consider the past, and find ways to deflect Gibney’s questions, the harder the emotional resemblance is to ignore.

As its subtitle suggests, Wise Guy is both a David Chase biography and a film about the making of The Sopranos, ultimately arguing that the two stories are one and the same. Some of what Gibney reveals will be familiar to Sopranos obsessives — as co-author of a book about the show, who has interviewed Chase too many times to count, there were a number of occasions where I began mouthing the words to certain answers along with him — but presented in a smart, propulsive fashion, likely to scratch a nostalgic itch for old fans while convincingly explaining what the big deal was to viewers who didn’t already binge the show during Covid. And there are enough revelatory moments — be it once-private anecdotes Gibney elicits, or old footage he and his team found — to make it more than satisfying even to people so steeped in the show’s world they can tell you which aging Family capo is Larry Boy Barese and which one is Ray Curto(*).

(*) Larry Boy is the one who got arrested multiple times, including at the premiere of Christopher’s horror film Cleaver, while Ray wore a wire for the feds, but died before giving them any useful information.

The documentary’s first half concerns itself with origin stories: first about Chase’s childhood, his relationship with a difficult mother who would one day be the basis for Tony’s malevolent mom Livia, and how he went to Hollywood to become a movie director and instead fell into a career as an episodic television writer who eventually dreamed up The Sopranos as the script that would finally get him into the film business. There are clips from early projects, some of them awful (Chase as both first assistant director and extra in, as he puts it, a “softcore sucking and fucking” WWII film about a desert fortress populated by German prostitutes), some much more promising (his first significant TV job was writing for the acclaimed private eye show The Rockford Files). Throughout, Chase comes across as smart, acidic, and as frustrated with himself as with the profession in which he began to feel trapped, taking the blame for not being more zealous in pursuing the directing career he wanted. (“Maybe I was too embarrassed,” he admits.)

Eventually, this leads into the development of The Sopranos, from rejections at the traditional broadcast networks (CBS boss Les Moonves didn’t like that the Mob boss was in therapy) to his eventual connection with HBO executives Chris Albrecht and Carolyn Strauss (both of whom appear in new interviews), and eventually to his chance to cast the series. What follows is the documentary’s first big showstopper sequence, where Gibney cuts together multiple audition tapes for many major Sopranos roles with clips of the final versions of those scenes from the actual show, played by the actors who won each role. Even if you’ve heard Chase talk before about what a miracle it was to find Nancy Marchand to play Livia, after all the other women had so utterly failed to evoke Chase’s mom, it doesn’t have nearly the impact that you get from a montage of the also-rans, followed by Marchand’s own audition, and then the polished scene. We also get glimpses of familiar Sopranos actors auditioning for parts other than the ones they got: Tony Sirico (a.k.a. Paulie Walnuts) for Big Pussy, and both Steven Van Zandt (who would go on to play Silvio) and John Ventimiglia (sad-sack chef Artie Bucco) for Tony. We don’t see either of Gandolfini’s auditions — both the one he stormed out of because he didn’t feel he was doing well, or the later one he did in Chase’s apartment that got him the job — but comparing every other actor’s version of Tony’s pilot speech about Gary Cooper to Gandolfini’s is like watching a bunch of rusty old cars puttering their way down a pothole-strewn road, and then seeing a spaceship blast into orbit.

Gandolfini’s story is so rich, and so complex, that it could fill a documentary all on its own, and that’s even before you get to his son Michael playing young Tony in the prequel film The Many Saints of Newark. (Wise Guy ignores Many Saints, though it does show a photo of Chase and James Gandolfini on the set of Not Fade Away, the autobiographical film Chase directed after the series ended, to minimal box-office results.) Chase and the various Sopranos actors interviewed do their best to convey their friend’s big heart, as well as to explain the many demons that haunted him, including struggles with drugs and alcohol; at one point, Chris Albrecht describes an intervention for Gandolfini that was somehow less successful than the one Tony and the other wise guys threw for Christopher on the show(*). But because the primary focus is Chase, because Gandolfini is sadly no longer with us to tell his story (he died of a heart attack in 2013), and because he hated talking about himself while he was alive, you definitely come away from Wise Guy feeling like there are substantial pieces missing.

(*) Albrecht is a necessary part of telling the story of the series, but he has also been accused of assaulting women on multiple occasions, and blamed at least one of those incidents on his own alcoholism. Having him as one of the key voices in the section about Gandolfini’s troubles, without providing any context for Albrecht’s issues in this area, feels extremely sketchy.

With so much ground to cover, Gibney also has to yada-yada other aspects of the show and Chase’s management style. Aida Turturro, Joe Pantoliano, Steve Buscemi, and the other memorable post-Season One cast additions aren’t interviewed, and most of the glimpses of those seasons involve stories focused on the original characters. (Chase, Van Zandt, and Drea de Matteo offer terrific insight on the way Adriana’s death scene was shot.) Meanwhile, writer Robin Green, who knew Chase for a decade before The Sopranos, talks about Chase firing her prior to the end of the series, and says she was guilty of all the misdeeds Chase accused her of, but the only one she’s willing to mention is that she often interrupted him while he was talking, and suggests that Chase began to place her into “that mother category.” There’s a whole lot to unpack there, and not quite enough time or candor with which to do it.

But Chase is remarkably open in so many other places, including in blaming himself for so many choices. He acknowledges that he used to get upset with the writing staff when they didn’t give him story ideas, and only later realized that they likely did this because he had a history of rejecting every pitch they brought him. And while he presented a fictionalized version of his mother to the world as a narcissistic monster, he eventually began to suspect that she had been abused as a child.

Inevitably, any conversation about The Sopranos must arrive at a discussion of the final scene at the ice cream parlor, with its divisive cut to black, and the question of whether this means Tony gets killed in that last moment. Chase hates being asked about this, but he reluctantly engages with Gibney on it to a degree, and (as he once did with me) agrees to talk about the thematic intention of the scene without explaining what, in his view, specifically happened. And Gibney the filmmaker responds in the only way left to him, with a punchline to the documentary that’s as amusing as it is inevitable.

In this 25th anniversary year, The Sopranos remains an awe-inspiring work, and Gibney is wise enough to often just let the series’ greatness speak for itself, with several amazing scenes — another psychiatrist trying to talk Carmela into leaving Tony, Tony and Carmela’s argument in the pool house after she tells him about her feelings for Furio — being presented almost in their entirety. No documentary, even at close to three hours, can capture everything. But Wise Guy is a strong celebration of the series, and a fascinating psychoanalysis of the man who dreamed it up.

Both parts of Wise Guy: David Chase and The Sopranos debut Sept. 7 on HBO and Max. I’ve seen the whole film.

Best of Rolling Stone