Why you'll never see the missing 17 minutes from '2001: A Space Odyssey'

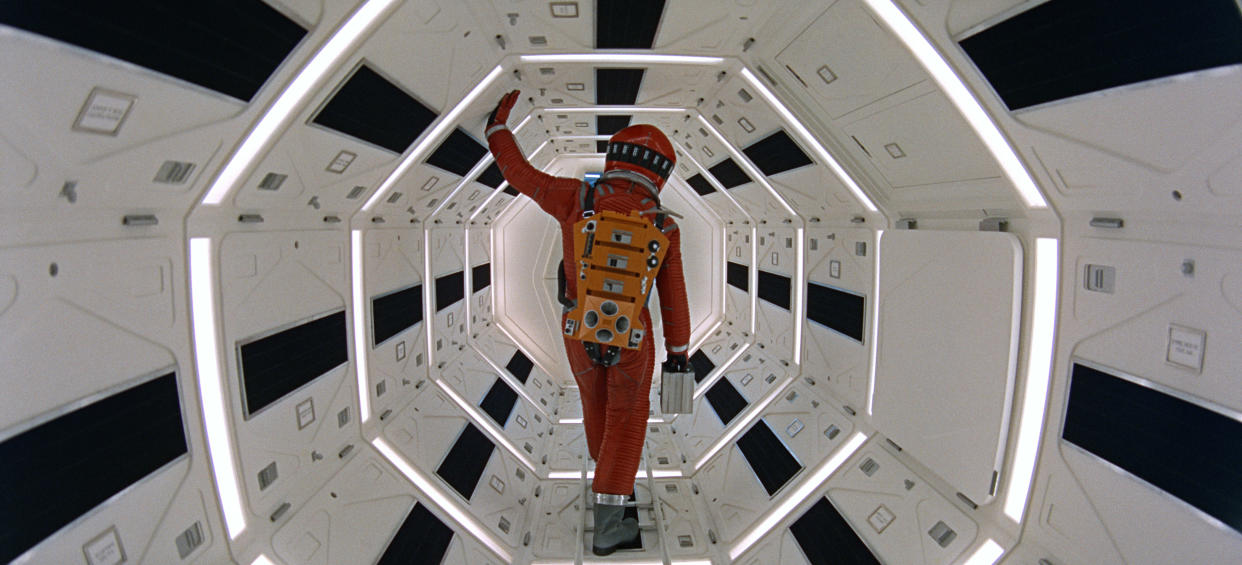

On Saturday, the Cannes Film Festival will travel back to the future when Christopher Nolan presents a 50th anniversary screening of Stanley Kubrick‘s sci-fi classic, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Like Kubrick, who passed away in 1999, Nolan is a vocal proponent for the supremacy of the analog cinematic experience, and intends for 2018 audiences to watch 2001 in the same way their 1968 predecessors did. Hence, the 70 mm print that will play at Cannes — followed by a theatrical rollout on May 18 — is largely free of any digital restoration, instead produced by printing elements from the original camera negative.

Still, there’s one part of the 1968 viewing experience that Nolan can’t duplicate for modern audiences. When 2001 first played for premiere audiences that April, the film was roughly 20 minutes longer than the one that subsequently went into wide release. The baffled reaction of those first moviegoers, as well as the studio, sent Kubrick back to the editing room to excise 17 minutes of footage. And unlike some filmmakers, he wasn’t concerned when it came to the film that ended up on the cutting-room floor. “Once he released a movie, that was it,” longtime Kubrick colleague — and subject of Tony Zierra’s new documentary Filmworker — Leon Vitali reveals to Yahoo Entertainment. “There’s a place in London where all the city’s refuse is taken, and I remember taking van loads of outtakes and stuff that was never used and burning them, because he did not want any of his old material.”

While Kubrick’s personal copy of those deleted 17 minutes most likely went up in smoke — perhaps during one of Vitali’s dump runs — it is worth noting that the footage still exists in the Warner Bros. vault. And as far as the studio is concerned, that’s where it’ll stay. That stance may disappoint film buffs, but it’s music to Vitali’s ears. “I truly believe that they should absolutely not do anything to interfere with the film as it is now,” he says emphatically. “If anybody has that kind of material, I would hope they’d say, ‘There’s a reason why he didn’t use it.'”

It’s worth nothing that few people enjoy the kind of access to material from Kubrick’s archive than Vitali does. Once a rising star in the British film industry, the 69-year-old actor began a nearly 25-year apprenticeship with the 2001 director when he was cast in 1975’s Barry Lyndon. In the wake of that film, Vitali largely abandoned acting in favor of being Kubrick’s right-hand man behind the camera. Filmworker, which opens in limited release on Friday, covers the full arc of their relationship and illustrates how Vitali still remains a keeper of Kubrick’s artistic legacy.

Even though Nolan is presenting the Cannes screening of 2001, Vitali worked on color-timing the 70 mm print, a function he frequently performed when his mentor was still alive. (Vitali adds that regrettably, press commitments will keep him from going to Cannes.) “Whenever there was a re-release or video transfer, he involved himself in making sure it was the highest quality that people could see. The BBC screened Stanley’s films one time, and he sent me to sit there and watch frame by frame and get them to [present it] the way he would have wanted to see it done.”

While Kubrick completed 2001 eight years before he and Vitali first collaborated together, it’s a film that loomed large in both of their careers. As Vitali recounts in Filmworker, it was the Kubrick production that expanded his mind about the possibilities of cinema as an art form. And for the director, it represented that rare case where the exacting pursuit of art triumphed over the immediate concerns of commerce. “The initial reaction to it — especially from [the studio] at the time — was, ‘Oh my God!'” explains Vitali. “They really wanted to radically monkey around with it. But through word of mouth, young people learned that this was a special kind of movie … and it grew into its own culture. That’s more gratifying than [a film] with a very short-lived reputation as a great movie. This thing has got roots and it’s grown; almost everybody talks about that film, especially filmmakers, who say what a visceral experience it was for them. Chris Nolan is presenting the film at Cannes in part because he says that when he saw 2001, it gave him the drive to want to make films.”

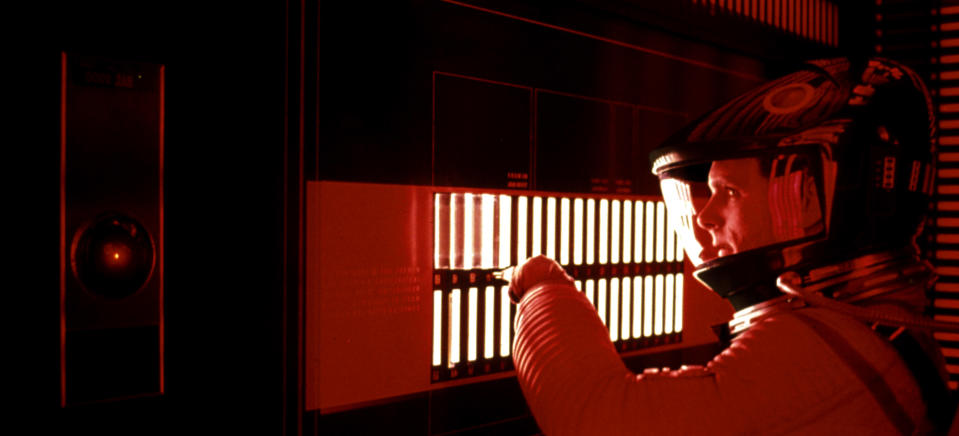

And then there are those filmmakers, like James Cameron, who throw a little shade at 2001 now and again. In April, the Avatar director caused a stir in film buff circles when he told the Toronto Star that as much as he loved the movie, it would benefit from “more emotional balls.” That’s a criticism Vitali is used to hearing leveled at 2001 and at Kubrick in general. Rather than argue against it, he says the “sterility” Cameron complains about in 2001 is a deliberate feature, not a bug. “It’s about a time in our human evolution, where there is a lack of emotion in what people work with,” he said. “I’m sure you can see that in life around us today. The movie was made at a time when we were beginning to move away from rural communities; everyone was moving to cities and working for big companies and they told you that you had work like this or like that. That’s still the case today — even more so. Stanley wasn’t a soothsayer, but he worked logically from that premise.”

Filmworker opens in limited release on Friday; 2001: A Space Odyssey returns to play in select theaters on May 18.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: