The 10 Dishes That Will Make You Fall in Love With Georgian Food

This collection of essential signature dishes showcases the unique splendor of Georgian cuisine.

Serious Eats / Georgian National Tourism Administration

When you arrive in Tbilisi, border agents don't just stamp your passport; they hand you a bottle of wine. It's a fitting welcome to Georgia, a mountainous country sandwiched between Europe and Asia, where dinner guests are exalted as "gifts from God" and traditional feasts called supras unfold in biblical proportions, sometimes lasting for days on end.

It's easy to lose track of time at the Georgian table. On a visit to the country's capital, I joined some friends for a dinner that entailed a dizzying array of salads, followed by steaming vats of heady stews and braises, gallons of orange wine, and occasional forays into polyphonic harmony, a signature feature of Georgian folk music. Staggering back to my hotel at 4 a.m., stuffed and delirious, I felt like I had emerged from a culinary fever dream.

The good news is, you no longer have to board a flight to the Caucasus to have a supra. In New York City alone, Georgian restaurants sprang up in. Georgia's distinctive orange wine, once known to only the savviest sommeliers, is now cropping up on wine lists across the country (some are even dubbing it the new rosé). And for DIYers, there's Darra Goldstein's encyclopedic, unrivaled cookbook, The Georgian Feast.

The Georgian Palate

Serious Eats / Shutterstock

So why are food lovers drawn to this faraway sliver of terrain smaller than South Carolina? For starters, it's hard to find dishes anywhere that so deftly intermingle Eastern and Western techniques: platters of soup dumplings, called khinkali, are as big an attraction in Tbilisi as they are in Shanghai, while Georgia's supple flatbreads parallel India's best naan, puffed and scorched on the inner walls of traditional clay toné ovens.

The similarities aren't coincidental. Sitting at the midpoint of ancient East–West trade routes, Georgians had the advantage of being able to cherry-pick the best of what the Greeks, Mongols, Turks, and Arabs were cooking along the Silk Road. When Russian poet Alexander Pushkin asserted that "every Georgian dish is a poem," I like to think he wasn't referring just to flavor and artful presentation but also to the coalescence of cultures on the plate.

Despite these outside influences, Georgian food remains steadfastly true to itself. Sure, meat stews may take on a sweet-tart dimension as they do in Persia, but pomegranate juice and sour fruit leather are more likely at work here, rather than the prunes and apricots thrown into the pot farther east. And while Georgian tomato salad, a mainstay of the summer table, resembles Mediterranean versions in appearance, it diverges in flavor with toasty notes from unrefined sunflower or walnut oil.

In fact, walnuts are the workhorse of Georgian cooking. An essential ingredient in menu stalwarts like chicken bazhe and vegetable pkhali (chopped salads), in pulverized form it's often employed in the same way that the French use butter: whisked into soups and sauces to add richness and body. Coarsely chopped and candied in honey, on the other hand, it makes for a satisfying if simple dessert called gozinaki.

Throughout Georgia, cooks are die-hard about sourcing the best local produce—that is, if the ingredient isn't already growing in their backyards. Perhaps it's this loyalty to freshness that explains why regional differences in Georgian cuisine have endured into the 21st century, despite the arrival of Carrefour and other international supermarkets. In the western provinces of Adjara, Guria, and Samegrelo, for instance, stews tinged brick-red with adjika (chile-garlic paste) will have you reaching for your water glass. Due east, where the cuisine is milder, the scantily spiced grilled meats of Kakheti are a study in minimalism.

Variation aside, there are certain dishes you shouldn't leave Georgia (or a Georgian restaurant) without tasting. These are the non-negotiables—the unforgettable bites that keep Georgia on my mind, and in my kitchen.

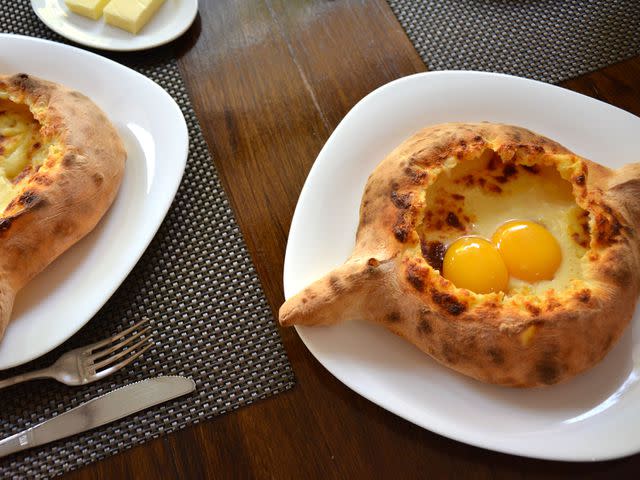

Khachapuri Adjaruli

Serious Eats / Department of Tourism and Resorts of Ajara A. R.

A molten canoe of carbohydrates and dairy, the quantity of sulguni cheese alone in khachapuri Adjaruli is enough to land a lactose-intolerant friend in the ER. But the decadence doesn't end there. Seconds after the bread is pulled from the toné, a baker parts the cheese to make way for a final flourish: hunks of butter and a cracked raw egg. When the bubbling mass is placed before you, you must wield your spoon fearlessly and, working from the yolk out, vigorously swirl the ingredients together until hypnotizing spirals of orange and white begin to appear. At this point—and God forbid the mixture get cold—tear off a corner of bread and dunk with conviction.

This is how Adjarians eat khachapuri, an umbrella genre of cheese-filled breads that are sold hot at hole-in-the-wall bakeries around the country. While each region has its favorite iteration of khachapuri—vegetables, meats, or legumes may be added—khachapuri Adjaruli has eclipsed the competition to become Georgia's national dish.

Churchkhela

Alexander Tolstykh / Shutterstock

Perhaps the most eye-catching Georgian food of all, churchkhela are the lumpy, colorful confections hanging in storefront windows, which tourists often mistake for sausages. Making churchkhela takes patience and practice: Concentrated grape juice (left over from the yearly wine harvest) must be poured repeatedly over strands of walnuts. Each layer is left to dry until a chewy, waxy exterior envelops the nuts. Packed with protein and sugar, churchkhela have even gone to war alongside the Georgian military, which relied on them as a source of shelf-stable nutrition. Nowadays, churchkhela are more often served at home with postprandials and coffee, but I have a hunch that they'll be gracing American cheese boards in the near future.

Khinkali

Serious Eats / Max Falkowitz

They say you can judge a good khinkali, or Georgian soup dumpling, by how many folds it has: Tradition dictates that fewer than 20 is amateurish. But when a platter of pepper-flecked khinkali hits the table, counting pleats is never anyone's first priority. Eating the khinkali is, and it requires urgency and exacting technique; without learning the latter, you risk being teased if you're in Georgian company. First and foremost, khinkali is finger food: Make a claw with your fingers and grab onto the dumpling from its topknot. Then, biting a small hole in the side, tilt your head back to slurp out the broth before sinking your teeth into the filling. Discard the topknot, take a swig or two of beer, sigh with pleasure, and repeat.

Historians speculate that khinkali, which bear a striking resemblance to Central Asian manti, were first brought to the region by the Tartars, who ruled what is now Georgia and Armenia for most of the 13th century. Today, the best sakhinkles (khinkali houses) are said to be found in Pasanauri, a village 50 miles north of Tbilisi, where wild mountain herbs like summer savory and ombalo mint accent the filling. If a khinkali pilgrimage isn't in the cards, though, Khinklis Sakhli is a favorite neighborhood spot among locals in Tbilisi.

Ajapsandali

Serious Eats / Georgian National Tourism Administration

Among the many riffs on ratatouille served throughout Europe and the Middle East, west Georgian ajapsandali stands out. For one, it's unapologetically spicy, with garlicky adjika taking a central role. And unlike its Mediterranean counterparts, in which the vegetables are too often reduced to mush, ajapsandali is an oven-roasted medley of firm eggplant and crisp bell peppers, lightly bound at the last minute with fresh tomato purée and livened up with a flurry of chopped cilantro. While customarily served in the final months of summer, when tomatoes and eggplant are bountiful, ajapsandali's warming and sinus-clearing properties make it optimal winter fare as well.

Lobio

Anna Bogush / Shutterstock

Who knew the kidney bean had such untapped potential? My eyes got wider as I swallowed spoonful after spoonful of lobio at Salobie, a restaurant in Mtskheta dedicated to this very dish. Texturally, lobio falls somewhere between refried beans and soup, a consistency achieved by pounding slow-cooked beans in a mortar and pestle, but the real revelation is in the flavor: A bracing slurry of fried onions, cilantro, vinegar, dried marigold, and chiles is stirred into the pot just before serving.

Lobio's loyal sidekick is mchadi, a griddled cornbread whose only function is ancillary. Reminiscent of Southern cornbread in its crumbliness, white color, and absence of sugar, it's one of the few Georgian breads that doesn't rely on the toné. Anyone with a skillet can make mchadi, which requires just three ingredients (cornmeal, salt, and water) and takes half an hour, start to finish.

Mtsvadi

Serious Eats / Georgian National Tourism Administration

Mtsvadi is Georgia's catchall name for meat impaled on a stick and cooked over an open flame. Variations on this theme abound in the region, but, in contrast with Turks and Armenians, Georgian cooks tend to be purists, eschewing elaborate marinades and rubs in favor of a liberal dose of salt. The preferred protein here is beef or lamb, cut into chunks and threaded onto a skewer, either on its own or with alternating slices of vegetables. But let me be clear—mtsvadi are anything but bland, especially when accompanied by tkemali, the sour plum condiment that Georgians pour over everything, from potatoes to bread to fried chicken.

Tklapi

Chubykin Arkady / Shutterstock

The first time I encountered tklapi, I thought it was a placemat. Flat, colorful, and over a foot in diameter, this peculiar Georgian specialty, as I would soon find out, is actually a Fruit Roll-Up at its most primal: puréed fruit, spread thinly onto a sheet and sun-dried on a clothesline. There are many types of tklapi; the sweet versions—like those made from fig or apricot—make a terrific snack out of hand, while sour ones—intense with tart cherries and foraged plums—are best used as souring agents in soups and stews. To find the best tklapi, stop at any of the rickety roadside shacks selling the stuff along the highways outside of town. While the villagers may not speak English, you can rest assured that you're getting a handmade product.

Kharcho

Natalia Lisovskaya / Shutterstock

Kharcho is Georgian comfort food at its finest, and it's become so popular throughout the region that Russians have incorporated it into their rotation of winter standbys. Amber in color and redolent of garlic, khmeli suneli (a Georgian five-spice blend), and cilantro, kharcho begins with chicken or beef, which is seasoned and seared before it's tucked into a sauce enriched with walnuts and perked up by torn bits of sour tklapi. After a couple of hours, when the meat is infused with spice and falling off the bone, the kharcho is ladled into bowls and served alongside baskets of chewy shoti bread, a savory vehicle for any leftover juices.

Pkhali

Serious Eats / Georgian National Tourism Administration

In a country where meat was historically reserved for special occasions, it's no wonder that elaborate vegetarian dishes continue to take center stage in Georgia's culinary canon. Pkhali, a family of salads that might be better described as vegetable patés, are made with whatever vegetable is on hand (beets, carrots, and spinach are common) and served over bread. The method is foolproof, to boot: Just boil the veg of choice, purée, and squeeze in some lemon juice, minced garlic, and a handful each of cilantro and ground walnuts for good measure. Georgian cooks will often whip up several types of pkhali, plating them side by side and sprinkling the tops with pomegranate seeds.

Lobiani

Magdalena Paluchowska / Shutterstock

Across from the Tbilisi History Museum, an unmarked staircase leading underground bustles with foot traffic. Follow the crowd and you'll stumble into one of the city's oldest bread bakeries, where fresh lobiani, flaky disks of bean-filled dough burnished by wood fire, are sold to a captive audience day after day, year after year. What's so seductive about beans and bread? For starters, lobiani is a handheld meal-in-one that costs less than a dollar. But beyond practicality, this humble flatbread is a symphony of textures and tastes. When you bite into an outer edge, it shatters and flakes like a Parisian croissant, giving way to a buttery center of spiced, bacon-scented beans. Put a beer in my other hand, and I can't imagine a food better suited to tailgating and picnics.

October 2015

Read the original article on Serious Eats.