14 Bars That Changed Cocktails Forever in America

Click here to read the full article.

Despite repealing Prohibition by passing the 21st Amendment in 1933, the dark ages of American cocktails lasted long after the country ended its Noble Experiment. The bars of America were fallow until a cocktail renaissance began to take root in the late 1990s and early 2000s. That’s when a collection of bars and bartenders started changing the way we drank.

When the revival began, we as a drinking public, had to acknowledge we had sinned. We’d let cocktails become synonymous with Lemon Drops and Appletinis and all things Carrie and Samantha from Sex and the City would have ordered at a night club where people lounged on beds. Listen, there’s nothing wrong with a well-made Cosmo, but we could do a lot better than vodka cocktails filled with high-fructose corn syrup and red dye no. 2.

More from Robb Report

The early influencers, like Milk & Honey and Angel’s Share in New York, had to bring us back to basics to break our bad habits. “It was almost in a weird way puritanical and purist to a fault by nowadays standards,” says Lynnette Marrero, bartender and co-founder of the all-women bartending competition Speed Rack. “But it needed to happen at the time. We needed to go so far back to the beginning to go forward again.”

Out were sour mixes and in were fresh ingredients. The cheap well whiskey was no longer enough; a rich and varied selection was required. Proper techniques to measure, shake and stir were back. Speakeasies proliferated. A quiet reverence to craft reigned in calm prohibition-inspired cocktail bars. But more innovation was to come. As early bars taught us how a good drink was made, new ones from New York to Portland to San Francisco spun those techniques forward with ingredients you wouldn’t find in a bar in the early 20th century. And soon, you could get a quality drink without having to be in some craft cocktail sanctuary.

“We won. I love the fact that I can now walk into a good bar and a guy in a ripped Megadeth t-shirt can make me a good Daiquiri,” says Joaquin Simo, owner of Pouring Ribbons in New York. “The bar has been raised across the country for better drinks in bars, restaurants and hotels. All of our proselytizing paid off.”

So it’s time to lift a glass to these establishments that pulled America out of the dark ages of drinking.

Angel’s Share

Where: New York

When: 1994

Influence: By bringing Japanese style to America, they reintroduced classic bartending techniques

This speakeasy-style bar hidden inside the Japanese restaurant Yokocho in Manhattan’s East Village put an emphasis back on technique when it came on the scene more than two decades ago. “After Prohibition, the craft of bartending went away, but it lived on in Japan, and they brought it back to the US,” says Jeffrey Morgenthaler, 2016 American Bartender of the Year.

The bar’s methods had a profound effect on Milk & Honey’s founder Sasha Petraske and many other New York bartenders. “Japanese bartending is a very distinct way of preparing cocktails,” says Giuseppe Gonzalez, a long-time New York bartender now based in Las Vegas. “Things like stirring cocktails, using fresh ingredients, freezing your own ice and measuring perfectly in jiggers. Everything is slower and more beautiful and intricate and the bartender took the time. They slowed down and controlled the energy of the room.”

This little oasis of calm contrasted with the hectic nature of New York. “Sitting at that bar across from Takuma Watanabe, I gained a friend and a place to escape the crazy city,” says Chicago-based bartender Julia Momose. “I try to go to Angel’s Share every time I am in New York, and each time, I come away with something.”

Absinthe

Where: San Francisco

When: 1998

Influence: Pioneers of house made ingredients

During the dark ages of cocktails, behind the bar it was all electric-colored artificial sour mixes, cranberry juice out of a gun and sugary corn-syrup concoctions. Not at Absinthe. “They didn’t have anything fake behind the bar,” says Erick Castro, owner of Polite Provisions in San Diego. This was a French Brasserie with a more culinary approach that went beyond ditching sour mix for actual fruit. “They were the guys who pioneered the idea of house made ingredients,” Morgenthaler says. “The first wave of new bartending got us to make fresh lemon juice and they were that next wave of making your own syrups and grenadine.”

“This bar doesn’t get enough credit,” Simo says. “Back then you were not seeing Sazeracs on a menu, especially not at a restaurant. They had a dense, annotated menu filled with classics and originals. They forced people to think beyond Cosmos, Lemon Drops and Kamikazes.”

Zig Zag Cafe

Where: Seattle

When: 1999

Influence: Huge spirits selection and rediscovering a Prohibition-era classic

Until barman Murray Stenson revived the prohibition-era cocktail The Last Word, it had been lost to history. The drink, which is equal parts lime, Chartreuse, gin and maraschino liqueur, travelled from his Seattle bar back to the cocktail hotbed of New York and became a mainstay of classic cocktail menus. “Zig Zag offered up the classics in such a sexy way and somehow kept finding old recipes to bring to their guests as if out of a magic hat,” says Anu Apte-Elford, owner of Rob Roy in Seattle.

But Stenson’s influence goes beyond a single drink. “At Zig Zag, Murray and those guys were doing everything before everyone pretty much,” Morgenthaler says. “Especially having a massive spirits collection. Now it’s commonplace to have a thousand different brands on the wall, but they were just doing it.” Even the baristas in coffee-mad Seattle looked to Stenson for inspiration. “I used to sit across from him at the bar and just learned from the way he moved,” says Christopher Abel Alameda of Menotti’s Coffee Shop in Venice, and formerly of Vivace in Seattle. “I learned how to interact with customers by watching him.”

Milk & Honey

Where: New York

When: 2000

Influence: Bringing back the classics

For many, drinking is about the destination. Shots, Long Islands, vodka-Red Bulls. Let’s get blotto, and let’s get there fast. Milk & Honey made it all about the journey. Like Angel’s Share, which inspired him, owner Petraske focused on craft, bringing a precision and formality back to bartending that made for amazing cocktails. He pushed back against sour mixes and sloppy technique by embracing classic cocktail ingredients and methods. You weren’t there to get smashed, you were there to enjoy what you were drinking, with Petraske in firm control. Then he spawned proteges who spread across the country from New York to Dallas to Los Angeles. “Without Milk & Honey the cocktail revival wouldn’t have happened as quickly as it did,” Marrero says.

But it wasn’t just the drinks that influenced the industry. Milk & Honey changed the vibe of bars. The early 2000s New York scene was a loutish affair. Milk & Honey was the apotheosis of that, adhering to strict rules of decorum, from “no starfucking” to “no hollering” to “no playfighting.” “It was like going to church in a lot of ways,” Castro says. “You went in there and you were in their world. You lived by their rules and on their terms and it was awesome.”

Bars aped Milk & Honey’s style. In the early aughts, if you saw a dapperly dressed bartender making craft drinks in a calm cocktail den, they were knocking off Petraske. People copied the bar so much, they almost turned what had been innovative into cliché. “The bad thing about Milk & Honey were all the people who copied it poorly,” Castro says. “You could copy the drinks but you couldn’t capture the atmosphere there. And if you weren’t there, you wouldn’t understand.”

Flatiron Lounge

Where: New York

When: 2003

Influence: Showing how cocktail bars could be a viable business

When Flatiron Lounge opened, the craft cocktail movement was still in its infancy and no one had yet proven it could make money. “Julie Reiner opening Flatiron is one of the most important bars in the movement. Look at the three bars before Flatiron: Blackbird closed in a year, Angel’s Share was happy being cloistered from the world and Milk & Honey was almost anti-capitalist with Sasha being hugely influential but never having any money,” Simo says. “Flatiron is the bar of the people; the bar pumping out an enormous volume of craft cocktails. It showed people you could have something better than sour mix from a gun, but you didn’t have to wait 20 minutes for your drink. A lot of people learned they liked drinking cocktails at Flatiron. It democratized the craft cocktail culture that had already set in.”

That success had knock-on effects. “If you don’t have Flatiron, you don’t have Pegu Club,” Simo says. “They have the same investors behind them and had Flatiron not been a great success, they wouldn’t have opened Pegu.”

Unlocking the money-making potential of cocktails owes to Flatiron owner and bartender Julie Reiner, who also owns Clover Club in Brooklyn. She’s trained some of the best bartenders in the business and taught them to be more efficient. “That woman knows how to make drinks really fast. She trains you to be fast. She trains you to be efficient,” Simo says. But what also made her was how she created an atmosphere for customers on top of having great drinks. “It’s what I admire most about her, she puts the customer first with super friendly service,” says Ted Kilgore, owner of St Louis cocktail bar Planter’s House. “And she really inspired me by having a place that’s volume that can still satisfy the cocktail geeks.”

Employees Only

Where: New York

When: 2004

Influence: The industry bar

In 2011, at the Oscars of booze (ok, it’s actually called The Spirited Awards), Employees Only won “World’s Best Cocktail Bar” further cementing its legendary status. “It’s easy to talk about their success now, but in 2004 they were the ugly child,” Gonzalez says. “EO had menus full of vodka cocktails when that wasn’t very cool.”

But this place wasn’t necessarily devoted to being cool, it wanted to be fun. “A lot of people go to bars where it’s very precious and regimented, and they end their night at EO,” Simo says. “That’s the party bar. You could still get good drinks. You can go pick someone up. There’s music. They take their job seriously, but they’re the antithesis of arm-garter wearing, jigger using mixologists. They care about the person in front of them. There’s less show about the pomp and circumstance. They weren’t precious in the way a lot of other bars were.”

At its core, its five people from the bar business teaming together to make the place they wanted. “It’s the industry bar and everybody wants to open up the next industry bar, but that takes determination and time and serving food until 4 AM,” Gonzalez says. “The game changer with Employees Only was you always had an owner making your drink. The first five years EO was open, every shift was covered by an owner. The degree of service you get from an owner is different than an employee. You’re not talking to someone who has a job, you’re talking to an owner.”

Pegu Club

Where: New York

When: 2005

Influence: The training ground for great bartenders

With the craft of cocktail making largely lost to time, bartender Audrey Saunders was a pioneer in re-establishing how to make great drinks. “Audrey’s style, the way she approaches cocktail creation, is outstanding,” Marrero says. “She’d try the Daiquiri 12 different ways before deciding what their house Daiquiri would be. That attention to detail was really important to the development of cocktails. She kept the craft going and was a great teacher.”

Some of the best bartenders in the business today honed their craft under Saunders at Pegu Club. “Me, Phil Ward, Kenta Goto, Jim Meehan all started at Pegu Club,” Gonzalez says. “Back when there were really only four bars in New York—Employees Only, Flatiron Lounge, Milk & Honey and Pegu Club—Pegu Club was the most ambitious. It was the ground zero of everything.”

Death & Co.

Where: New York

When: 2006

Influence: Bringing new ingredients to the bar to build on the classics

With the basics relearned at spots like Milk & Honey, a second wave of bars could now thrive, led by Death & Co., which opened in the East Village on New Year’s Eve in 2006. “Death & Co. is so progressive, they changed the way people see cocktails,” Kilgore says about his visits to New York to learn about the cutting edge of the bartending craft. He greatly admired how they experimented with blending spirits so an old fashioned wasn’t just one whiskey out of a bottle, but a collection of them that created a unique flavor profile. And he also saw how different spirits could play off each other in one drink. “We started different spirits together, like a gin that worked with a tequila or a scotch that worked with a mezcal,” he says.

“It was the first that did really complicated drinks,” says Castro. “Milk & Honey is very austere, very clean and simple drinks. Using techniques from 100 years ago. Very traditional. I was most inspired by Death & Co. They’d use tarragon, honeydew juice or other things you’d not find in pre-Prohibition bars. They had more modern techniques and more ingredients than just classics, but the drinks were every bit as delicious.”

The Violet Hour

Where: Chicago

When: 2007

Influence: The Midwest Mecca

Opened by a veteran of Milk & Honey and Pegu Club, Toby Maloney, The Violet Hour brought a refined, New York-centric approach to cocktails to the Windy City. But, with rules like Milk & Honey’s, not everyone liked it at first. “It was polarizing, people fucking hated that bar,” Simo says. “They didn’t’ want to be told they couldn’t stand, that you couldn’t wear a hat.” But people who did adhere to the rules received not just Milk & Honey on a larger scale, they also had really innovative drinks. “This notion of thinking way out of the box and subverting the cocktail canon came out of Violet Hour. You’d see guys testing drinks together until 6 AM after a shift was over,” Simo says. “You wouldn’t have the Aviary unless Grant Achatz and the Alinea crew wasn’t coming in all the time and drinking there after service. They saw people pushing the envelope in the same way they were.”

Alums from The Violet Hour have spread out opening great bars in their own right, but even before that happened, bartenders came from all around to learn. “It had a huge effect on how people drank in Chicago and throughout the Midwest,” Simo says. “People who came to visit The Violet Hour went back to Detroit, Cleveland and Indianapolis and opened their own bars. You wouldn’t have seen the growth of cocktail culture in the middle of the country without it.”

Clyde Common

Where: Portland, Oregon

When: 2007

Influence: Barrel-aged cocktails and open-sourced innovation

Thousands of miles from the cocktail hotbeds of New York and San Francisco, Jeffrey Morgenthaler still managed to connect with his peers through a blog informed by his work behind the stick. “He has a website that’s not for cocktail nerds, it’s a bartender’s site,” Gonzalez says. “With Jeff, he was the first bartender to tackle the problems we all face and speak about it in an intelligent way.” And that meant driving innovation behind the bar and then having an open source ethos where he’d share what he found. “Living where there weren’t really cocktail bars yet, there was no place to go and sit in another person’s bar and watch, so reading that blog helped me,” Kilgore says. “And he had strong opinions, which challenged me to develop my own opinions on how to do my job.”

But at Clyde Common, there was innovation happening on top of teaching the basics. “He’s just a crazy creative guy. He’s one of those dude that created a lot of trends,” Castro says. “When you look at things like barrel-aged cocktails in the modern era and bottled cocktails, that was him.” He’s also turned Disco-era drinks like the Long Island Ice Tea, Grasshopper and Amaretto Sour into respectable cocktails. And as Repeal Day celebrations happen around the country now every December 5, drinkers everywhere can thank Morgenthaler for creating that boozing holiday too. “Jeff is the people’s champ,” Gonzalez says. “And he’s still bartending so you can’t fuck with him.”

Seven Grand

Where: Los Angeles

When: 2007

Influence: The rebirth of cocktails in America’s second-largest city

“LA didn’t exist until after Seven Grand opened,” Morgenthaler says. Sure, the City of Angels existed before 2007, but not to the cocktail world. Los Angeles got a late start on the revival compared to New York and San Francisco, much like how the renewal of its urban core began after other metropolises. When Seven Grand opened in 2007, much of the block it occupies in Downtown LA was just abandoned buildings and the city wasn’t too interested in a dedicated whiskey bar, but it went ahead anyway. “Seven Grand returned the notion of classic drinking to Los Angeles,” says Ryan Wainwright, who won the U.S. Bar Guild’s Legacy Cocktail Competition in 2017. “A lot of places in town are still following what they did. I still look to their model.”

Other bars have become more famous since Seven Grand, including The Varnish, which won Best American Bar at the 2012 Spirited Awards. “Varnish gets all the accolades and awards,” Wainwright says. “But Seven Grand is the one who stood up and invested in an ideal, put it out there and said ‘let’s see what happens’”

Drink

Where: Boston

When: 2008

Influence: The custom cocktail experience

When you walk into Drink, it’s a pretty different experience than most any bar you’ve visited. There are no bottles on the back shelf to give you a clue about what spirit to select, nowhere to sit other than right at the zig-zagging bar and no menu for you to look at. “Your only recourse is to talk to the bartender and it’s designed it that way,” Gonzalez says. “Some people are so focused on making a menu that it almost becomes kitsch. But we want someone to come in and talk. It’s a beautiful way to create community.”

“What they did better than anybody else was they showed how critical the interaction between a bartender and guest was,” Simo says. “It shouldn’t be limited to putting this massive tome of cocktails in front of you that you may not understand, and then walking away. Instead, it’s ‘Let’s have a chat, what are you in the mood for?’ You get a drink made just for you.”

Smuggler’s Cove

Where: San Francisco

When: 2009

Influence: Rescuing tiki

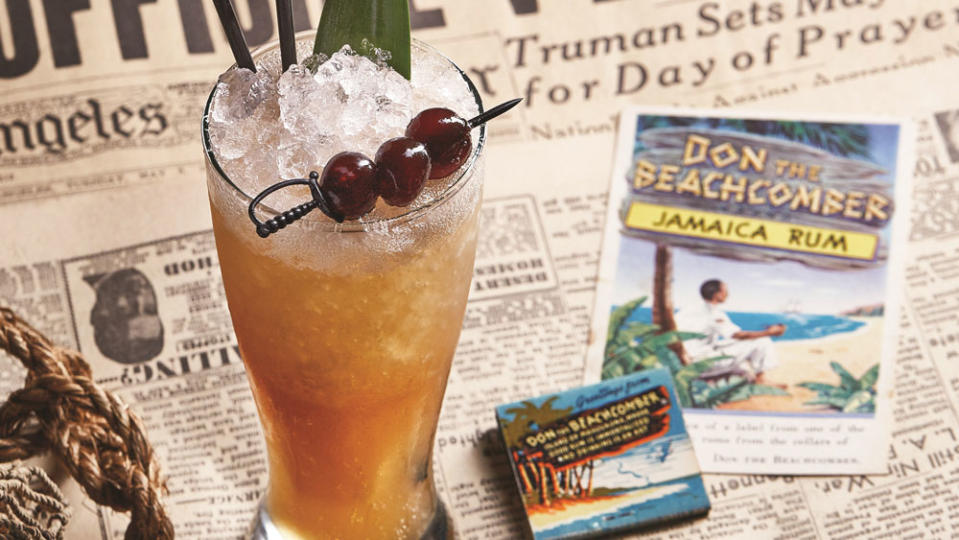

If you’re enjoying a delicious Mai Tai or Zombie, first you’ve got to thank Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic, the godfathers of tiki. But really, the vaguely Polynesian fad fell so far out of favor toward the end of the 20th century that by 1989 even Donald Trump deemed Trader Vic’s to be too tacky for residency in one of his properties. But now tiki is back. Bars dedicated to tropical drinks have popped up across the country, with bartender Martin Cate leading the way. So if you’re drinking tiki today, you should be toasting to his bar Smuggler’s Cove.

Tiki began as an escapist fantasy during the Depression and peaked as a full-on cultural and drinking phenomenon during the mid-century. The décor flamed out along with the drinks, which can be pretty complicated to make. Each cocktail may have multiple fresh juices, different types of rum and a few house-made ingredients to boot. It took Smuggler’s Cove embracing tiki in full, from styling to ingredients to show people again how it could be done. “It’s part cocktail bar, part amusement park. It’s escapism. It’s inspiring and I get ideas from them,” Gonzalez says. “Do you want a boring prohibition bar or do you want a fun Tiki Bar?”

Rickhouse

Where: San Francisco

When: 2009

Influence: Puncturing the pretension that had set in with cocktail culture

As the craft cocktail scene grew, a bar almost needed to put on an air of seriousness in order to be taken seriously. Sometimes the drinking got a bit dour. “At the time, every bar was a speakeasy,” Castro says. “Rickhouse was a response to that. There were some bars doing fresh juice and stuff doing high volume, but they weren’t to the precision of Death & Co. We said, let’s do both. Rickhouse took all the seriousness of a craft cocktail bar and then combined it with loud music, rock and roll and a good time. That’s why it won so many award out of the gates. So many people game in craving the whole time.”

Bartenders in the area took notice, including Wainwright, who cut his teeth in the Bay Area before decamping LA. “I was a guy I came from dive bars up in San Francisco, and we wanted to do something more upscale. And so we copied Rickhouse,” Wainwright says. “People would come in talking about what they got over there.”

“They showed we don’t need to open a speakeasy, we can open a bar and let people come in and enjoy themselves,” Kilgore says. “They left the snobbery behind.”

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.