15 Black Artists Who Shaped Country Music

Rhiannon Giddens

Beyoncé’s new album, Cowboy Carter, has finally arrived, and as many fans suspected, it’s in part a tribute to Black artists who’ve gone ignored in country music, as Renaissance was a love letter to house.

As the woman herself put it, “This ain’t a country album. This is a ‘Beyoncé’ album”—but Cowboy Carter could certainly teach casual country fans a few things they didn’t know about the genre. The album features two spoken-word intros from Linda Martell, the first Black woman to play the Grand Ole Opry, as well as guest appearances by contemporary stars Tanner Adell, Brittney Spencer, Tiera Kennedy and Reyna Roberts.

Related: Every Beyoncé Album, Ranked

If Cowboy Carter has piqued your interest in Black artists’ foundational role in the history of country music, then Rissi Palmer is one of the best people you could turn to to learn more. Palmer, who in 2007 became the first Black woman to chart a country song in 30 years, is the host of Apple Music’s Color Me Country, where she highlights artists of color who have too long gone ignored in a genre that has remained incredibly resistant to change.

“My biggest goal was just wanting to make sure that artists of color had a platform where they could go, where they felt comfortable enough to just tell the story, not to edit the story, not sugarcoat the story, but just tell the story,” Palmer says of her radio show. “And also I wanted to course-correct, because so much of this stuff has been hidden and has been kept from the general public. I don't think on purpose. I think more so just because people don't see it as important, and it is important. And I'm trying to, with the show, actively combat erasure.”

Here, Palmer shares her thoughts on Martell and 14 more Black artists who are essential to understanding the history of country music—and where it’s going next.

15 Black artists who shaped country music

1. Lesley Riddle

Most country fans know the Carter Family as some of the earliest pioneers of country, but far fewer know that Mother Maybelle learned her technique from a Black man. “He was a pastor and a master guitar player who was missing fingers on his left hand,” Palmer says of Riddle. “And it caused him to have to change the way that he played because of that, and he developed this very distinctive style of playing. Basically, what is known as [Maybelle’s] distinctive guitar playing style—he taught that to her. He was also the person that went out and gathered the music for [the Carter Family’s] first record. A lot of that music came from Black people. It came from Black churches. It came from music that was being sung by enslaved people in the field, music that they were sitting around playing around the campfire and that sort of thing."

"One of the biggest songs that the Carter Family is associated with is ‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken?' It's written in the Country Music Hall of Fame on the walls, and it's this song that Black people have been singing in church for years. Lesley is very much tied to the lore and iconography of the Carter Family and does not get the credit I think that he deserves for that.”

2 and 3. Etta Baker and Elizabeth Cotten

Photo by Sylvia Pitcher/Redferns

Palmer draws a direct through line from Baker and Cotten to Beyoncé's “Texas Hold 'Em,” which features a distinctive guitar sound and Rhiannon Giddens’ banjo playing. “They are both pioneers of the Piedmont blues guitar style,” Palmer explains of Baker and Cotten, who were both from Palmer’s native North Carolina. “It's like a rolling guitar kind of lick, and they both were originators of that. These were just two women that were master guitar players. When we think of blues, we always think of older Black men. We don't often think about Black women, but they had a very distinctive style, so much so that Bob Dylan, Taj Mahal, all these people have cited them as influences on their playing style and their singing style. ‘Going Down the Road Feeling Bad’ and ‘Freight Train’ are two songs that I think are exemplary of their technique and their playing style that has influenced the American songbook from the moment that they were released.”

4. Lil Hardin Armstrong

Hardin was Louis Armstrong’s second wife and a successful musician and composer in her own right, but her achievements have been greatly overshadowed by those of her famous husband. “She was an accomplished pianist and she was a bandleader at a time when women, especially Black women, were not leading bands,” says Palmer. “She and Louis Armstrong arranged and played on Jimmie Rogers’ ‘Blue Yodel #9,’ and they were uncredited. They're all over it. In future years, as Louis became famous, people gave him credit for that, but people rarely give Lil the credit for that. And as far as my knowledge is concerned, she's the first Black female to play on a country album with that song.”

Related: 25 Sad Country Songs for When You Need a Good Cry

5. DeFord Bailey

Bailey, a harmonica player who was posthumously inducted into the Country Music Hall of Fame in 2005, was the first Black performer to be featured on the Grand Ole Opry. “That was the first sound that you heard whenever you turned on the Grand Ole Opry radio show,” Palmer says of Bailey’s work. “He was one of the cast regulars and could not even stay in the same hotel with his peers and never received the renown that he deserved, which meant that wasn't able to translate that into a full career, nor was he able to translate that into financial stability.”

6. Ray Charles

Photo by James Kriegsmann/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Charles is known as a pioneer of soul, but in 1962, he released Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, which helped point the genre in a new direction even though it wasn’t embraced by country radio. “So many Black artists at this time grew up listening to country,” Palmer says. “Back then there weren't that many radio stations, and so radio stations would just play a lot of different genres at the same time. So, many Black people, myself included, grew up listening to country in the same way that they consumed R&B and gospel and all these other things. And then to take it even further, because of religion and religious beliefs, so many Black people were not able to listen to secular music, and so they could only consume gospel music and country music.”

Charles had already been reshaping other genres with his earlier work, and he did the same thing with country on Modern Sounds. “He was a master at that,” Palmer explains. “He took these songs and turned them into these lush arrangements and just these really soulful, beautiful versions. You are hearing them in a completely different way than you did with the original records. And because of Ray, you can also make a direct tie to the change in Nashville in terms of these very lush arrangements and the lush background, vocal arrangements, and that sort of thing. But country radio didn't touch this record at the time when it was released, and it was only celebrated in pop and some in R&B.”

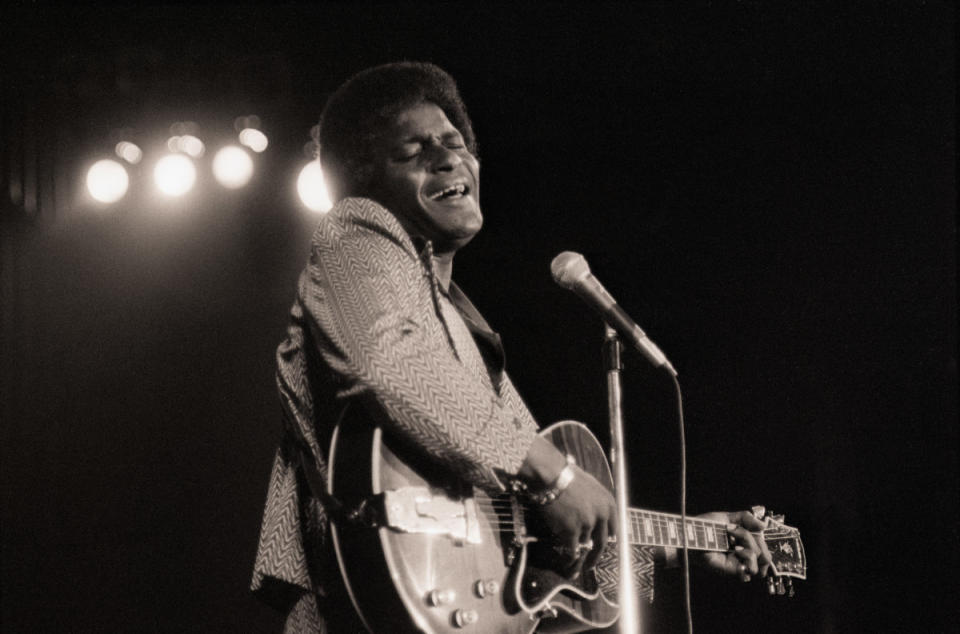

7. Charley Pride

Bettmann / Contributor / Getty

Pride, who was a Negro League baseball player before he was a country star, is one of the most successful country artists of all time, charting 30 No. 1 hits throughout his career and becoming one of only three Black members of the Grand Ole Opry.

“Ray Charles doing Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music and the subsequent success of that record are completely directly tied [to Charley],” Palmer says. “You can make the argument that one happened because of the other, meaning Charley happened because of Ray Charles. And even though he was loved and was welcomed into the fold, he faced racism from his peers. There are very well-documented stories of Willie Nelson calling him the N-word, or George Jones writing [KKK] on the side of his car. Those are things that are ugly, and we don't like to think about them because George Jones and Willie Nelson are two of the icons of country music, but this is what the climate was like for him, and they were ‘joking’ with him. And so Charley took all of this abuse and unfortunately had to do it with a smile and keep his head down and keep moving.”

8. Linda Martell

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Martell, as mentioned, is actually on Cowboy Carter, delivering powerful words about the slipperiness of genre. “Genres are a funny little concept, aren't they?” she says on “Spaghettii,” which also features Shaboozey. “In theory, they have a simple definition that's easy to understand, but in practice, well, some may feel confined.”

Martell’s first and only album, Color Me Country, was released in 1970 and served as the inspiration for the title of Palmer’s Apple Music show and her grant fund. “Her story is so exemplary of so many stories in the space,” Palmer explains. “She was sought after because Shelby Singleton, who owned the record label that she was signed to, Plantation Records, was looking for a female counterpart to Charley Pride. That was pretty much the onus for every Black female that got signed at this time, was to be a counterpoint to Charley Pride. So much of the literature that I found whenever I'm researching is these record companies saying, ‘Oh, she's the female Charley Pride,’ or, ‘She's Charley Pride in a skirt,’ or all these different things. And so they weren't really being sought after for their own individuality. They were being sought after literally as a marketing tool to be the counterpoint to Charley.”

Martell’s album and several singles landed on Billboard’s country charts, but Singleton dropped her from Plantation after her labelmate Jeannie C. Riley started blowing up with the song “Harper Valley P.T.A.” Martell cut another album for a different label, but Singleton made sure that she never got to release it.

“Shelby so cruelly blacklisted her in Nashville, so nobody would touch her,” Palmer explains. “So she ended up having to leave and go back to South Carolina and raise her family. And she drove a school bus for a while and never stopped singing, never stopped performing locally, but just never got the attention and the dues that she really deserved and was robbed of the career that she absolutely could have had.”

9. Tina Turner

Photo by Paul Natkin/Getty Images

For those surprised to see Turner on this list, Palmer has this to say: “The woman is from a town called Nutbush, Tennessee! I don't know how much more country you could be.”

Like Charles, Turner was raised on country music, and her first solo album, 1974’s Tina Turns the Country On!, featured covers by country icons like Dolly Parton and Kris Kristofferson. She earned a Grammy nomination for the album in 1975—in the R&B category, despite the fact that “country” is right there in the title.

“I actually have this album framed in my office,” Palmer says. “I love the cover so much, and I love Tina Turner, so this is a personal favorite of mine. And again, this did not receive any attention from Nashville or from the country charts or country radio.”

10. Alice Randall

Randall is a true polymath: she’s a songwriter, a novelist, a cookbook author, a professor and more. She was one of the few Black songwriters on Nashville’s Music Row, and she wrote the 2001 novel The Wind Done Gone, which retells Gone With the Wind from the perspective of an enslaved woman. On the music front, her most famous track is “XXX's and OOO's (An American Girl),” which was cowritten with Matraca Berg and became a No. 1 hit for Trisha Yearwood in 1994.

“I call her my fairy godmother,” says Palmer, who appears on next month’s Randall tribute album, My Black Country: The Songs of Alice Randall. “I say that because Alice has been just such an incredible advocate for me and for Black women in this space, and specifically making sure that they are paid what they are worth. She's an incredible songwriter, but more than anything, she's just a really effective advocate for us. Alice came to Nashville specifically to be a country songwriter, and I also think that's an important distinction, because out of all the Black women that have written songs that are hits, like Tayla Parx and Muni Long and even Donna Summer, Alice is the only one out of all of them that is specifically a country songwriter that came here to do that. She's just a very cool person. For a long time, she was the publisher for Garth Brooks, and she's had songs cut by Glen Campbell and George Strait and so many of the people that we think of as country music royalty.”

11. Rissi Palmer

Photo by Erika Goldring/Getty Images

Palmer, to be clear, did not ask to be included on this list, but she deserves to be here all the same. In 2007, she became the first Black woman to chart a country song in 30 years with her debut single, “Country Girl.” She’s since released three solo albums (and is currently at work on her fourth) and has collaborated with fellow Black country groundbreakers like Miko Marks and Gangstagrass. In addition to hosting her Color Me Country radio show, she also cofounded a grant fund of the same name to support underrepresented groups in country music.

12. Rhiannon Giddens

Photo by Al Pereira/WireImage

Giddens, like Martell, appears on Cowboy Carter, playing banjo on “Texas Hold ’Em.” While her music falls more into the folk and Americana categories, she’s done a ton of work to make sure that people know the banjo was invented by enslaved Black people. In addition to her solo work, Giddens has released music as part of the band Carolina Chocolate Drops and the group Our Native Daughters, which also includes Amythyst Kiah, Leyla McCalla, and Allison Russell.

“On top of the fact that she's written operas, she has done all of this really great music historical work,” Palmer says. “She is a strong, fabulous, well-versed, seasoned musician, and first and foremost, a classically trained singer. So that instrument is tip-top, and I'm really glad that people are getting to be reintroduced or introduced to her for the first time because she really is incredible. Without trying to sound like a fangirl, she's another woman that I admire greatly and have been really inspired by. She's not a commercial country artist, and that's not a dig. She is an old-time bluegrass performer, and I think she would even tell you that, but she has made an indelible mark.”

13. Mickey Guyton

Photo by Jason Kempin/Getty Images for CMT/Viacom

After Palmer landed on the charts with “Country Girl,” it was eight more years before another Black woman achieved the same milestone. That was Guyton, whose 2015 song "Better Than You Left Me" hit No. 34 on the Country Airplay Chart. In 2020, she became the first ever Black woman to earn a nomination in the Best Country Solo Performance category, for her song “Black Like Me.”

“It’s wild to think that it took another eight years for there to be another Black woman chart,” Palmer says. “Mickey was, at the time when she dropped her first single, the only Black woman signed to a major label. Now that's not true, there are others, but she was one of the only ones. Mickey's had a really interesting career in that it took her 10 years to release her debut album, which is wild when you look at her peers. It took ‘What Are You Gonna Tell Her?’ and ‘Black Like Me’ for her to kind of break out. Country radio has not budged to play her and to play any of these songs, and so she continues to work, but she is a byproduct of what happens when country radio does not support you, because it's very hard to have a career when you don't have the backing of country radio.”

14. Chapel Hart

Photo by Carly Mackler/Getty Images

“Chapel Hart, I think, are superstars,” Palmer says of the trio, which is made up of sisters Danica Hart and Devynn Hart and their cousin Trea Swindle. “The fact that they're not signed and they're not on a major tour right now is baffling to me. They've been on America's Got Talent, they've had Loretta Lynn singing their praises and they’re regulars on the Opry, and they're just incredible musicians. I had the pleasure of taking them to Europe to be a part of the Color Me Country takeover stage at the Long Road Festival. And when I tell you they damn near caused a riot when they tried to get off the stage at this afterparty that they were performing at—they were only supposed to sing three songs, they ended up doing a 90-minute set. It was incredible. They just have this effect on people whenever they see them. The genre is missing out on some big energy by not taking a chance on Chapel Hart.”

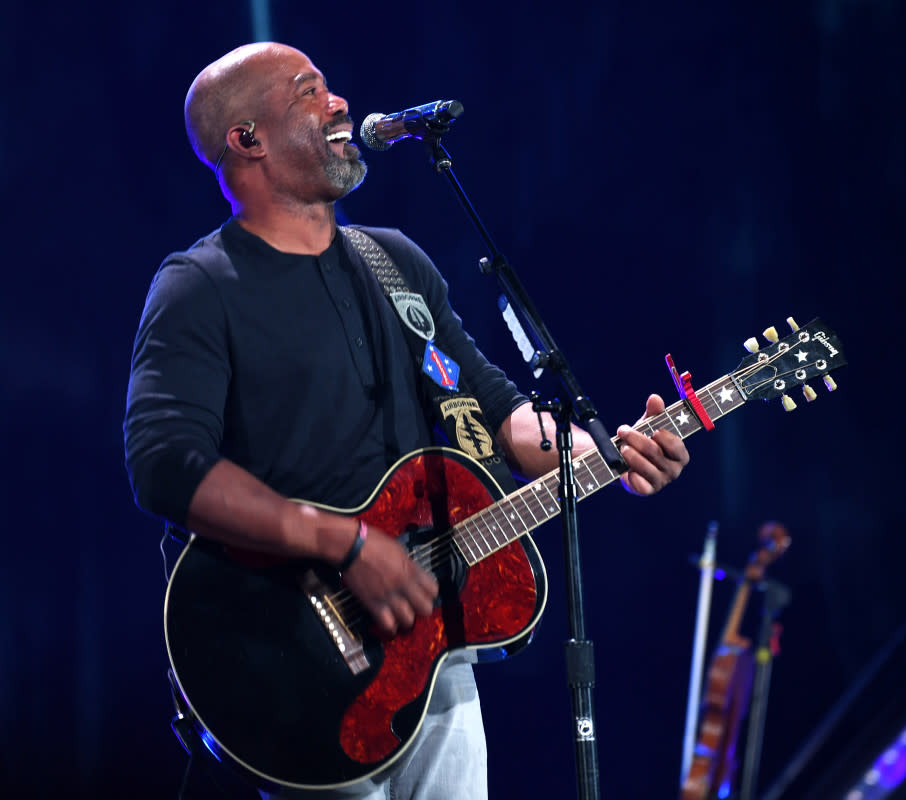

15. Darius Rucker

Photo by Denise Truscello/Getty Images for iHeartMedia

After fronting the ’90s staple band Hootie & the Blowfish, Rucker pivoted to country music, eventually becoming one of only three Black members of the Grand Ole Opry. Though Rucker had years and years of experience under his belt by the time he began working in country, he’s been open about the fact that he’s faced discrimination from the establishment.

“Darius came into the situation being a superstar through Hootie & the Blowfish. You would think, ‘Oh, he's probably had a really easy time.’ I had him on the show and he talked about some of this stuff for the very first time, the way that he was treated when he first came to Nashville, and the skepticism and the outright racism that he faced at radio, trying to get people to play the first single,” Palmer says. “I don't think on the surface you would think that that's what was going on with him, because you see him getting No. 1s and doing all these tours and fishing with all the other artists and that sort of thing. But in the very beginning, it was really hard for him. It just goes to show you that it doesn't matter how famous you are, it doesn't matter how much money you have or anything. You still at some point have to face some of these realities, unfortunately.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.