'Eff you and goodbye': How the bravest among us quit their jobs in style

As President Trump himself might say, it was the best way to quit. A tremendous way. One of the greatest ways of all time. A bigly, bigly, yuge way to go.

For 11 dramatic minutes on Thursday night, the @realDonaldTrump account (41.7m followers, following just 45) disappeared from Twitter, sparking fevered speculation. Had the tech giant taken action against the maverick US leader for threatening nuclear war? Had the FBI seized it to search for links to Russia? Had Trump himself accidentally deleted it due to his notoriously tiny fingers?

No, the explanation turned out to be even better. By Friday morning, it emerged that an employee at the social network had deactivated the account as a farewell stunt on their last day.

Twitter was immediately flooded with messages congratulating the rogue staffer responsible. People insisted they be promoted rather than sacked, offered to crowd-fund a leaving gift and promised they need never buy a drink again. Former Republican congressman David Jolly said the mystery Trump-silencer “could be a candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize”.

“Not all heroes wear capes,” added comedian Kumail Nanjiani, star of tech sitcom Silicon Valley.

This plug-pulling act of sabotage also provided a chance to relive some of the all-time top last day pranks. Trump isn’t the first US president to be the butt of the joke. Shortly after George W Bush was elected in 2000, his team discovered that White House aides working for predecessor Bill Clinton had removed or broken the “W” keys on all computer keyboards in the West Wing - somewhat problematic when Bush distinguished himself from his father by using his middle initial.

Neither is disappearing Donald J the first to fall foul of Twitter revenge (aka “Twivenge”). Staff sacked by retail chain HMV got even in 2013 by hijacking the company’s official feed and live-blogging the “mass execution of loyal employees”. The string of posts began: “We’re tweeting live from HR where we’re all being fired! Exciting!”

Over-worked producer Marina Shifrin also went viral in 2013 when she quit her job at a Taiwanese animator by making a video entitled: “An Interpretive Dance For My Boss, Set To Kanye West’s Gone”. The clip saw her dancing jubilantly around the office at 4.30am, while subtitles outlined her grievances.

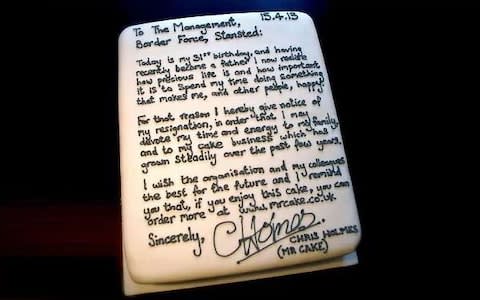

The same year, Stansted airport worker Chris Holmes quit to start his own baking business - so fittingly, iced his resignation letter onto a cake. And who can forget the Forth Road Bridge employee who programmed an electronic road sign to warn drivers about high winds: “Blowy as f---, man (also my last day)”?

There was the duty manager of a Taco Bell/KFC outlet in New York who, after 22 straight days on shift and being told he couldn’t have take the fourth of July off, shinned up the illuminated sign and wrote in metre-high lettering over Highway 78: “I quit - Adam. F--- you” - followed, with lovely bathos, by a smiley face.

Steven Slater, a cabin crew member on America’s JetBlue airlines, became a cult hero when he snapped due to passenger rudeness on a 2010 flight and, as the plane touched down, seized the intercom to announce: “Those of you who have shown dignity and respect, thanks for a great ride. But I’ve been in this business 28 years and I’ve had it, motherf-----.” Slater grabbed his bag and two beers from the drinks trolley, pulled the lever of the plane’s emergency chute, calmly slid down to the tarmac and strolled off.

Less demonstrative but no less impactful - especially in the internet age, when they invariably go viral - are well-aimed farewell letters.

In 2007, a JP Morgan employee’s parting shot did the rounds after it drily stated: “I’ve been fortunate enough to work with some interchangeable supervisors on a wide variety of seemingly identical projects - an invaluable lesson in overcoming daily tedium”.

A Whole Foods worker’s epic 2,300 word resignation note (that’s twice as long as this article) spread like wildfire in 2011, after it described the grocery chain as “a faux hippy Wal-Mart”, accused it of mistreating staff, underpaying and not living up to its own eco-ethos - before ultimately exhorting colleagues to “quit being cowardly wieners”.

There is a certain poetry to such resignations. They’re a last word, a cathartic way to unleash pent-up frustration. With nothing left to lose, downtrodden employees are suddenly liberated. They can sign off in style, then sassily strut out of the building to a brighter future.

Stories about two-fingers-up farewells give a vicarious thrill to those who would probably never do it but are happy to fantasise. They have us inwardly cheering, glancing longingly at the door and daydreaming about doing something similar. It’s an irresistible variation on “if I won the lottery” escapism.

There’s now even a book about them, The Last Goodbye: A History of the World In Resignations by Matt Potter. Its original title, before being updated for a more mainstream market, was the rather more colourful F--- You And Goodbye.

Final bows can backfire, though. A disgruntled friend of mine who worked at a men’s magazine repaired to the pub one lunchtime with his equally unhappy coterie. They worked themselves up into a lager-fuelled frenzy of mutinous intent.

Returning to the office full of Dutch courage, my friend unsteadily climbed onto his swivel chair, gave a slightly slurred speech about how his colleagues were “mediocre brown-nosers and maggots”, then stormed out, expecting his pub posse to follow. Suddenly sober, they kept their heads down and avoided eye contact. He found himself slinking out alone, tail between his legs.

Indeed, there’s a proud and potty-mouthed history of such gestures in journalism.

Only last week, an aggrieved writer for Doctor Who magazine - who also happened to be a former Dalek operator on the time travel romp - was sacked after sneaking a none-too-flattering message about his employers into the latest issue. Nicholas Pegg’s article ended with the line “If you look hard enough, there’s always something hidden in plain sight”.

Lo and behold, the first letters of each paragraph read “Panini and BBC Worldwide are c---s”. The ex-Dalek’s contract was duly exterminated.

In the early Nineties, an obscure motoring journo named James May got fed up putting together Autocar magazine’s annual review of the year and deliberately got himself sacked by spelling out a not-so-secret message in the large red capitals that began each section: “So you think it’s really good, yeah? You should try making the bloody thing up. It’s a real pain in the arse.” May, of course, went on to have the last laugh by hosting Top Gear and The Grand Tour.

A Daily Mirror cartoon of the Berlin Wall, back in 1989, included the squint-and-it’s-legible scrawl “F--- Maxwell”, aimed at the tabloid’s reviled proprietor. The final edition of The News of the World in 2011 cunningly hid its revenge on boss Rebekah Brooks in the crossword. “Disaster”, “menace”, “stench” and “racket” were among the answers, while clues included “Woman stares wildly at calamity”, “string of recordings”, “criminal enterprise”, “mix in prison”, “Brook” and “catastrophe”.

The Trump Twitter quitter, then, performed just the latest in a long line of last day heroics. It seems a formal letter, a dutifully served-out notice period and a few drinks down the local pub simply don’t cut it anymore. Nowadays, normal quitting is for quitters.