The Best NFL Moments Ever

The Best NFL Moments Ever

From the Immaculate Reception to David Tyree's helmet catch, see the most memorable plays in NFL history, as selected by football experts.

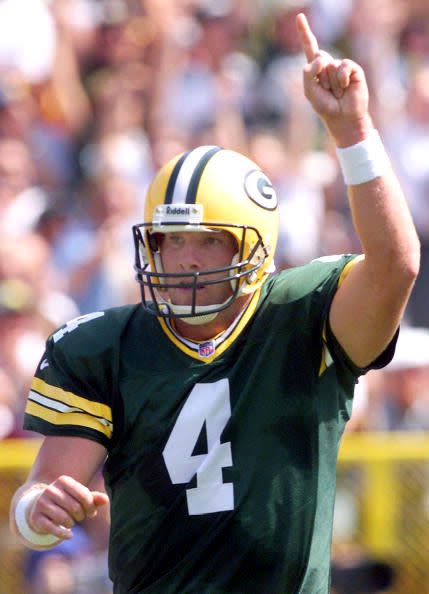

50. The Iron Man Is Born

Brett Favre’s Hall-of-Fame career is filled with enough brilliant—and boneheaded—moments to fill a lifetime’s worth of SportsCenter clips.

But perhaps none of them would exist if he doesn’t fill in for injured Packers quarterback Don Majkowski on September 20, 1992.

In relief, Favre chucks a 35-yard scoring strike to receiver Kitrick Taylor with a minute left, defeating the Bengals in a 24-23 thriller.

And the next week, in the quarterback’s true first start for the Cheeseheads, Favre finds Sterling Sharpe and Robert Brooks on different plays to scorch the Steelers’ defense.

Green Bay wins, 17-3, and the Packers become Favre’s team for good.

Says Jon Gruden, color commentator for ESPN’s Monday Night Football and an assistant coach for the Pack at the time: “[Favre’s start] ignited the Green Bay Machine that we know today, which has resulted in a lot of good fortune for Packers fans.”

Favre will go on to start a record 297 consecutive games at quarterback, an Iron Man record that’s likely to remain unbroken until robots start playing football.

Related: The Better Man Project—2,000+ Incredible Health Tips You Need in Your Life

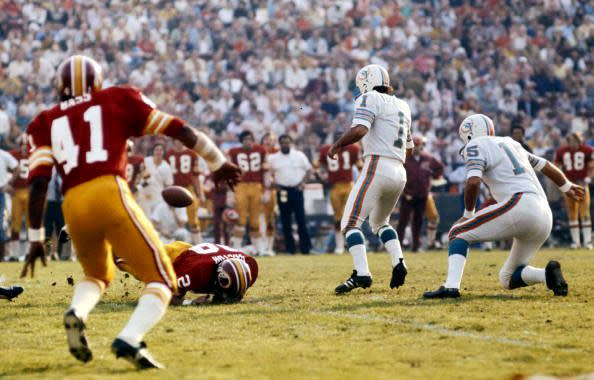

49. Garo Makes a Mistake

With less than two minutes to go in the season, the 1972 Miami Dolphins are looking to cap their perfect year with a Super Bowl win against the Washington Redskins. The Dolphins are up 14-zip, and placekicker Garo Yepremian is set to attempt a 42-yard field goal that should put the game well out of reach for the Redskins.

The snap, hold, and kick look good. But the kick is blocked, and bounces toward the midfield line.

The Dolphin kicker chases down the football. But instead of falling on the ball and conceding the play to the ‘Skins defense,

Yepremian tries to throw it downfield. The ball slips out of Yepremian’s hand on what looks like a pathetic attempt at a forward pass, bounces off the kicker’s own helmet, and lands in the hands of a Washington defender, who scampers 50 yards down the sideline for a touchdown.

“Miami may have capped its perfect season in 1972 by beating the Redskins, 14-7, in the Super Bowl, but that victory is highlighted by this lowlight that provided Washington its lone touchdown in the fourth quarter,” says Jim Gigglioti, football historian and author of The Official Treasures of the National Football League.

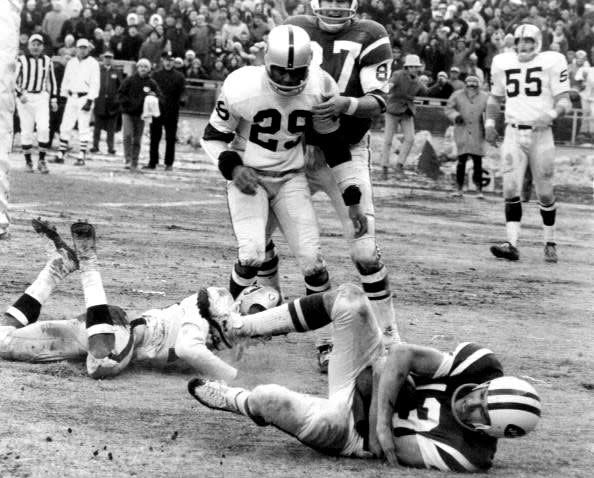

48. Marshall's Wrong-Way Run

Toward the end of a midseason game against the 49ers in 1964, Vikings defensive end Jim Marshall pulls off what some will ultimately call one of the most embarrassing plays in professional sports.

In the fourth quarter, Marshall scoops up a Niners fumble and races toward the end zone nearly 70 yards away—the wrong end zone.

With both teams chasing him down the field, and his own teammates screaming to him from the sidelines, Marshall goes into the end zone untouched and tosses the ball out of bounds in celebration, resulting in a safety for San Fran—and heaps of scrutiny from the media.

While the play doesn’t affect the Vikes’ eventual victory, a new legacy is born.

Jim Buckley, editor of NFL Magazine, says, “Jim Marshall didn’t deserve to be remembered this way. When he retired, he held the record for longest consecutive-games-played and was a fierce defender for the Vikings for almost two decades.”

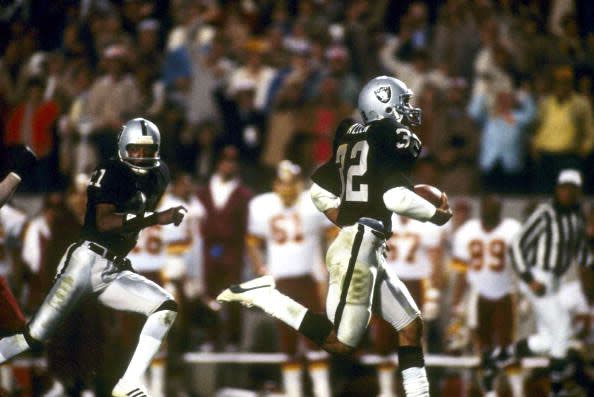

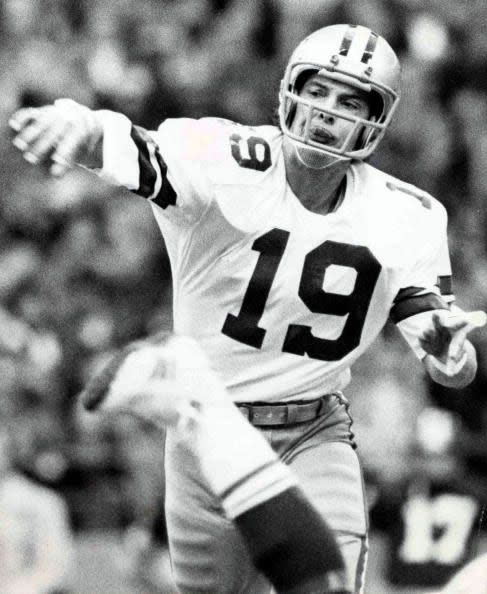

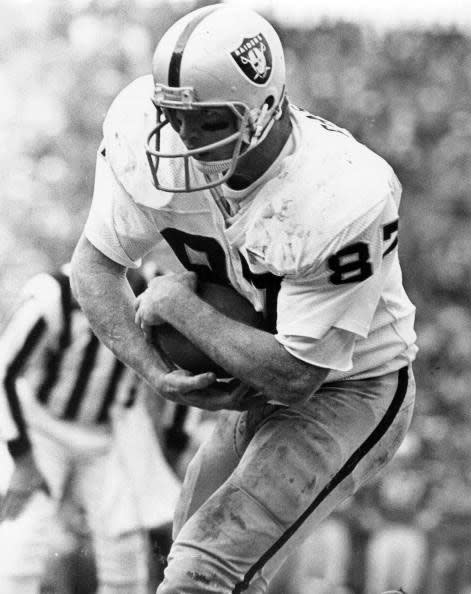

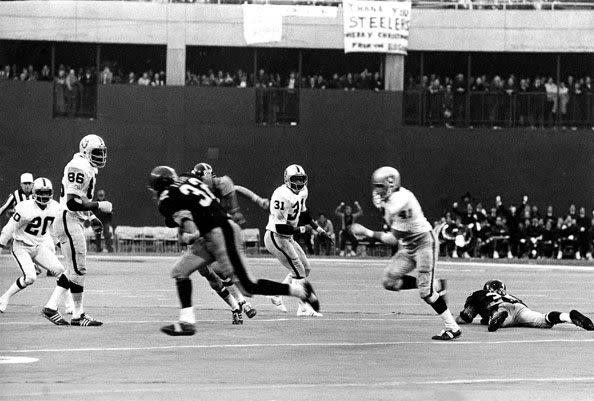

47. Allen Shows His Instincts

Things have gone from bad to worse for the Washington Redskins during Super Bowl XVIII as the Oakland Raiders offense takes the field near the end of the third quarter.

The score stands at 28-9 in favor of the silver and black, and the Redskins know they’re in for a big dose of Oakland running back Marcus Allen as the Raiders hope to run out the clock.

With just a few seconds left in the quarter, Oakland quarterback Jim Plunkett hands off to Allen near the Raiders’ own 25-yard line. Running left toward a phalanx of defenders, Allen reverses gears and spins back toward the right side of the field.

“Allen’s amazing football instincts took over on a play that began as a run around left end,” remembers Jim Gigglioti, football historian and author of The Official Treasures of the National Football League. “When that was bottled up, he spun all the way around, found a crease up the middle, and took off on what was then the longest run in Super Bowl history.”

Seventy-four yards later, Allen is in the books, while the Redskins’ championship hopes are finished.

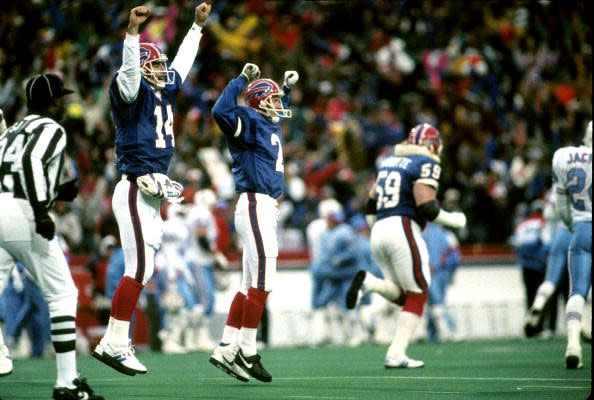

46. Buffalo Roars Back

Following Houston’s 27-3 romping of Buffalo in the final game of the 1992 regular season, the Bills—led by Jim Kelly’s backup, Frank Reich—find themselves facing a similar fate in the first-round of the ensuing playoffs.

Down 35-3 in the second half, Reich and the Bills score five unanswered touchdowns en route to a 41-38 victory, capped by a game-winning field goal in overtime.

The largest comeback in NFL history, the Bills’ victory propels the team through the playoffs and into the Super Bowl, where they eventually lose to the Dallas Cowboys for the third of their four straight Super Bowl losses.

Still, “it was one of the greatest comebacks I have ever seen,” says Jon Gruden, color commentator for ESPN’s Monday Night Football and a Super Bowl-winning coach himself.

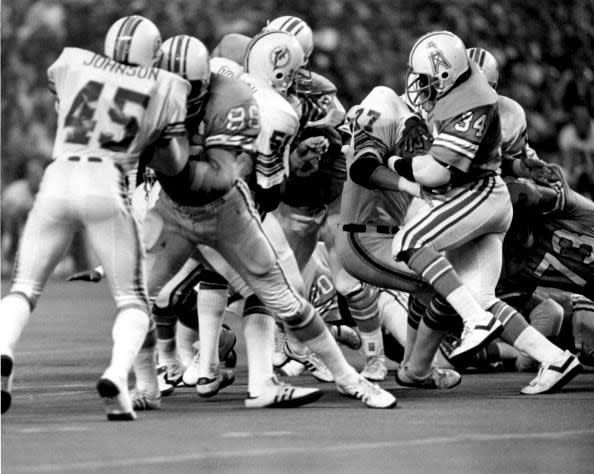

45. A Monday to Remember

In a classic 1978 slugfest, Houston’s rookie running back sensation Earl Campbell outduels Miami’s gunslinging quarterback Bob Griese in a prequel to the first-round playoff matchup that will occur five weeks later.

While Griese posts impressive numbers of his own—23-for-33 for 349 yards and two touchdowns—Campbell’s 199 rushing yards and four touchdowns seal the win for the Oilers.

The Houston tailback’s performance is highlighted by two scores in the final seven minutes, including an 81-yard touchdown run with just over a minute left in regulation.

Campbell will go on to win Rookie of the Year and Offensive Player of the Year honors that season.

“I remember Earl Campbell running over Isaiah Robertson during the time of those tearaway jerseys and thinking, ‘Oh, my!,’ ” says Jon Gruden. “

He was just a different kind of beast playing the tailback position. During his performance on Monday Night Football, he ran over people all night.”

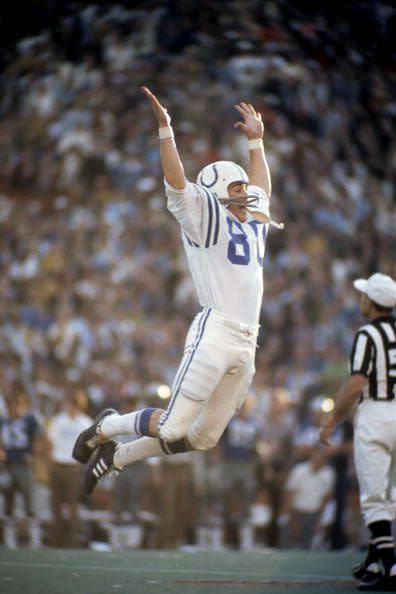

44. O'Brien's Foot Delivers

Time is running out on a mistake-riddled Super Bowl V. The Baltimore Colts have drawn even with the Dallas Cowboys, after trailing, 13-6, at the half.

The two teams have combined for an embarrassing 11 turnovers and a slew of penalties, including 10 for the Cowboys alone. Baltimore quarterback Johnny Unitas is forced to leave the game with an injury during the first half, and now Dallas must drive down the field for the win.

Cowboys quarterback Craig Morton throws toward his running back, Dan Reeves. But the ball sails through Reeves’ hands, and into the arms of Baltimore linebacker Mike Curtis, who returns the interception to the Dallas 28-yard line. Two plays later, the Colts rest their championship hopes on the shoulders of rookie placekicker Jim O’Brien.

“The rookie kicker was so nervous that he tried to pick up a blade of grass to gauge the wind, but the game was played on artificial turf!” recalls Jim Gigglioti, football historian and author of The Official Treasures of the National Football League.

O’Brien overcomes his nerves, and nails the 32-yard field goal to seal the 16-13 win for the Colts.

43. Pollard's Punishing Hit

Following their perfect 16-0 regular-season campaign in 2007, the Patriots open the 2008 season in Kansas City as Super Bowl favorites with a healthy Tom Brady under center.

Midway through the first quarter, however, Chiefs safety Bernard Pollard fights through a block and dives at Brady from the turf, hitting his left knee square on and ending the quarterback’s season.

Without Brady running the offense, the Pats miss the playoffs.

While Pollard’s controversial hit is ruled legal initially, the rulebook’s roughing-the-passer infraction is amended a year later to outlaw defenders from lunging at quarterbacks while on the ground.

“When Bernard Pollard went in low and hurt Tom Brady, protection of quarterbacks became paramount in this league,” says Jon Gruden.

42. Osmanski Bears It All

Bears fans making the trip to Washington D.C.’s Griffith Stadium for the 1940 NFL Championship are treated to the finest fireworks show they’ll likely ever see, as the Monsters of the Midway trounce the Redskins, 73-0.

But it’s Bears running back Bill Omanski’s beastly run that “epitomized the Chicago rout of Washington,” says Ray Didinger, an award-winning sportswriter and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

On the second play of the game, from his own 24, Bears quarterback Sid Luckman reverse pivots and hands the ball to Osmanski off tackle. The back dips inside and then swings wide left past one defender to see nothing but open field in front of him.

As two Redskins begin to close around the 35-yard-line, Bears end George Wilson comes in to obliterate both, allowing Osmanski to set the tone for the rest of the game.

For great health and fitness advice delivered right to your inbox, sign up for the Daily Dose newsletter today!

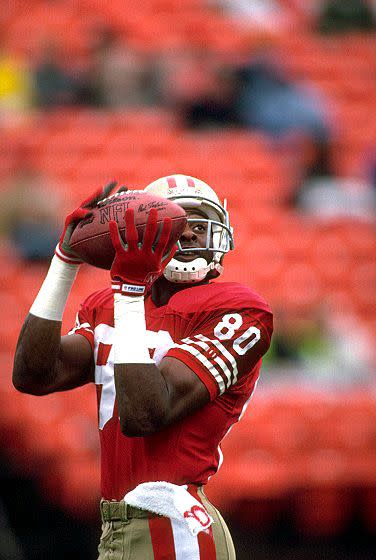

41. Victory with a Side of Rice

It's the second game of the 1987 NFL season, and the Bengals hold a 26-20 lead over the 49ers with just seconds to play. Cincinnati only sends four players to rush Joe Montana, leaving the rest of the defense in the end zone to bat down any pass the Niners QB might toss up.

Inexplicably, however, the Bengals leave Jerry Rice—the game’s most freakishly talented and fearsome receiver—wide open in the back-right corner of the end zone.

As the ball zips out of Montana’s hand, Rice leaps up and brings down the game-winning touchdown. And there isn’t a defender within an arm’s length.

“In the old Riverfront Stadium in Cincinnati,” says Jon Gruden, “people found out you never, ever single-cover Jerry Rice in any situation.”

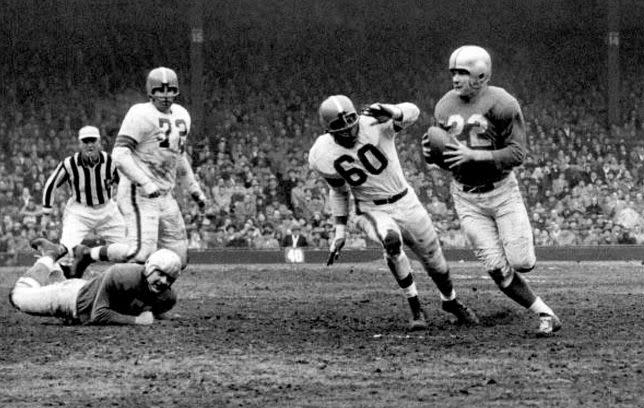

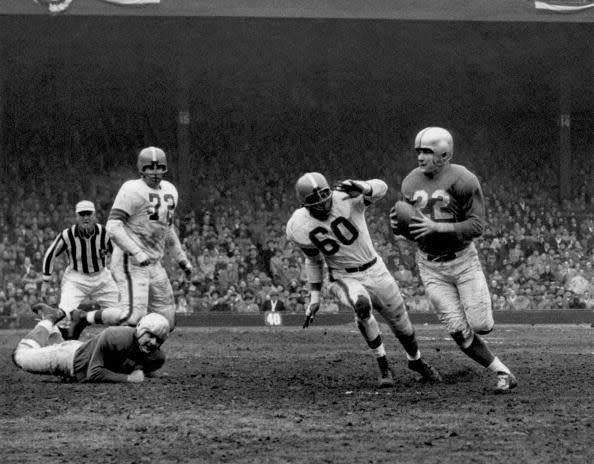

40. Doran Goes Deep

The Cleveland Browns are battling the Detroit Lions in the 1953 Championship Game. Lions receiver Jim Doran has been telling his quarterback all day that he can beat his coverage for a deep bomb, but Detroit’s Bobby Layne is patient and continues to soften the Bears D with shorter passes.

With just over two minutes to go in the game and the Lions down, 16-10, Layne finally decides to take his shot. Doran sprints past his man and is 10 yards beyond the nearest Brown when he hauls in the pass and skates into the end zone untouched.

The extra points give the Lions the lead and the championship.

“The pass epitomized the clutch play of Layne, the quarterback of whom it was said, ‘He never lost a game. Time just ran out on him,’ ” says Ray Didinger.

Related: THE 21-DAY METASHRED—One Guy Lost 25 Pounds In Just 6 Weeks By Following This Body-Shredding Plan!

39. Young Thinks On His Feet

Playing for the injured Joe Montana in a 1998 matchup with the Vikings, backup quarterback Steve Young and the 49ers trail Minnesota by a touchdown with less than two minutes to play.

San Francisco calls for a pass play on third-and-short at midfield, but after dropping back, Young’s pocket collapses.

Famously called by San Francisco broadcaster Lon Simmons, Young spins out of a sack, and—unable to find an open receiver—scrambles up the middle, twisting through the secondary and breaking six tackles as he stumbles into the end zone. The 49-yard touchdown run gives the Niners a lead they wouldn’t relinquish.

“Few players in NFL history could improvise as well as Young, the Hall of Fame quarterback, and this play was his signature moment,” says Jim Gigglioti. “It was important, too, because it helped keep the eventual Super Bowl champs afloat while starting quarterback Joe Montana was injured.”

38. Concrete Charlie Knocks Out Gifford

First place in the NFL’s Eastern Conference is on the line as the Giants host the Eagles in 1960. New York jumps out to a 10-point lead, but Philadelphia battles back to tie it in the fourth quarter.

The Eagles force a fumble that they return 38 yards for a TD to take their first lead of the game. After New York ties it up, things look good for the home team.

Frank Gifford sneaks out of the backfield and catches a pass across the middle of the field, but in fighting for extra yards, the halfback is met by Chuck “Concrete Charlie” Bednarik in a collision that will be called the most famous tackle in NFL history. (And thanks to the hit, Gifford doesn’t return to the gridiron until ’62.)

“It forced a fumble that saved a critical win for the Eagles in their drive to the championship that season. One Hall-of-Famer on another Hall-of-Famer making a play that changed the directions of two teams,” says Ray Didinger.

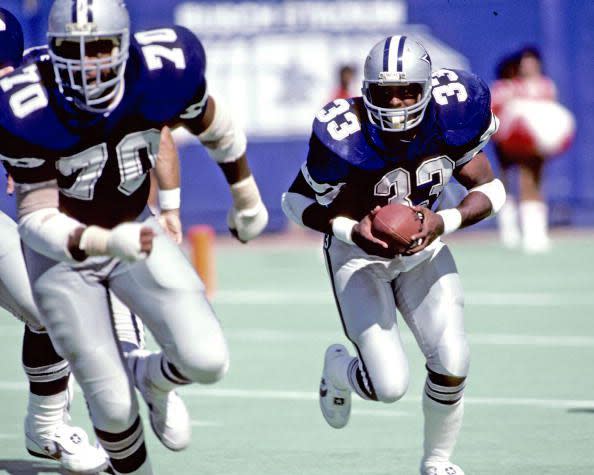

37. Dorsett Breaks Free

Trailing the Vikings by a couple of scores in the fourth quarter on Monday night in the final game of the 1983 season, the Cowboys are pinned inside their own 1-yard line.

In an attempt to wrestle a semblance of breathing room, Dallas calls for a simple halfback dive through the one-hole.

Former Heisman winner Tony Dorsett receives the handoff and bursts through the defensive line, breaking three arm tackles in the second layer of defense and stiff-arming a defensive back en route to a touchdown and the longest run from scrimmage in NFL history.

Dorsett’s 99-yard scamper is a record that can never be broken and has yet to be matched. “And, a remarkable footnote: Dallas had only 10 men on the field for the play,” says Jim Gigglioti.

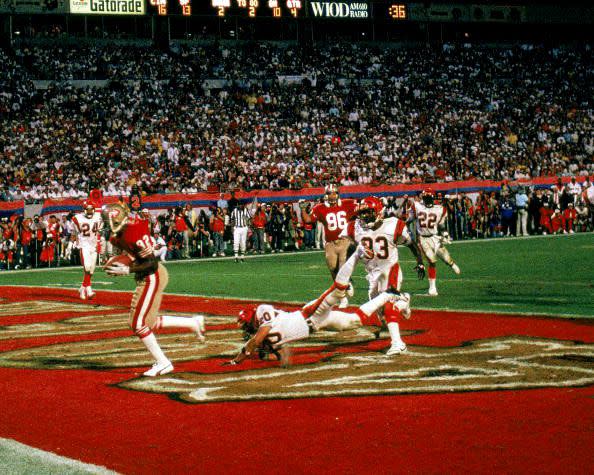

36. Taylor's Fantastic Finish

Cincinnati has just kicked a go-ahead field goal to take a three-point lead with three minutes left in SuperBowl XXIII. In a contest mostly controlled by the defenses, only one offensive touchdown has been scored.

With just 39 seconds remaining, all eyes are on San Francisco receiver Jerry Rice, who has already racked up a Super Bowl-record 215 yards.

Fellow Niners receiver John Taylor, who has gone the entire game without a catch, lines up to the right, as Rice goes in motion to the same side. Taylor cuts to the inside and quarterback Joe Montana hits him in stride for the game-winning touchdown.

Taylor, who is primarily used as a returner, only has 14 catches to his name that year, and none are as important as his first Super Bowl reception that gives San Francisco the victory.

“The Super Bowl had been a super dud for several seasons, with a series of lopsided blowouts,” says Jim Gigglioti. “But this was the first time the lead changed hands in the final minute of a Super Bowl.”

35. Longley's Long-Shot Comeback

As millions of Americans prepare to eat their Thanksgiving Day dinners in 1964, the Dallas Cowboys are trailing the Washington Redskins, 16-3, in the third quarter of their holiday matchup.

Legendary Dallas quarterback Roger Staubach is injured, and rookie QB Clint Longley is tasked with leading his team back from the dead.

And that’s exactly what he does: Longley proceeds to hit tight end Billy Joe Dupree for a 35-yard touchdown completion. Most fans assume the play is a fluke—just beginner’s luck.

But Longley then leads the Cowboys on another touchdown drive, this time for 70 yards. Despite the rookie’s heroics, Dallas still trails the Skins, 23-17, with 28 seconds left on the clock and no timeouts.

Longley, to the surprise and delight of a stadium packed with hysterical fans, connects down the middle with Drew Pearson for a 50-yard touchdown. The Cowboys win, 24-23.

“It forced Americans to postpone their holiday meal until this miraculous comeback was over,” remembers former NFL head coach and current color commentator for ESPN Monday Night Football, Jon Gruden. “The NFL has become such an important part of the Thanksgiving holiday, and it’s because of dramatic games like this one.”

34. Ingram Fights for a First

At the start of Super Bowl XXV, the Buffalo Bills are predicted by most to easily outgun the New York Giants defense. But as the third quarter gets underway, the game is a defensive battle, and the Bills hold a slight, 12-10 advantage.

The Giants face a third-and-13 from the Buffalo 33-yard line, and as quarterback Jeff Hostetler surveys the field, he can find no one open past the first-down marker. He dumps the ball off to wide receiver Mark Ingram, his underneath target, who proceeds to make five Buffalo tacklers miss as he ducks and spins his way toward the first-down marker.

As multiple Bills’ defenders converge, Ingram hops forward past the marker, securing the first down. The Giants soon score to make it 17-12, and eventually seal the game with a fourth-quarter field goal.

“But the Giants don't get into position to win without the second and third effort from that scrappy little receiver,” says Jarrett Bell, football writer for USA Today.

33. Chuck Secures the Championship

Led by coach Vince Lombardi, the Green Bay Packers enter the 1960 NFL Championship Game against the Philadelphia Eagles feeling confident. Even though the game is being played in Philly, the Birds are massive underdogs, and soon find themselves trailing the Pack.

Although Green Bay dominates the game statistically, the Eagles fight back, and take a slim, 17-13 lead with just a few minutes remaining. The Packers drive down the field, but are out of timeouts when running back Jim Taylor breaks into the open.

With just half a minute to play, Eagles linebacker Chuck Bednarik is the only man between Taylor and the end zone.

Bednarik, however, is up to the task, and wraps up the shifty running back at the 10-yard line.

“This day belonged to Bednarik,” says Jim Gigglioti, football historian and author of The Official Treasures of the National Football League. “He played the entire game on both offense and defense,” a feat unheard of in the modern-day NFL.

Yes, Green Bay goes on to win multiple titles during the ‘60s, but Bednarik’s tackle saves the Eagles their championship.

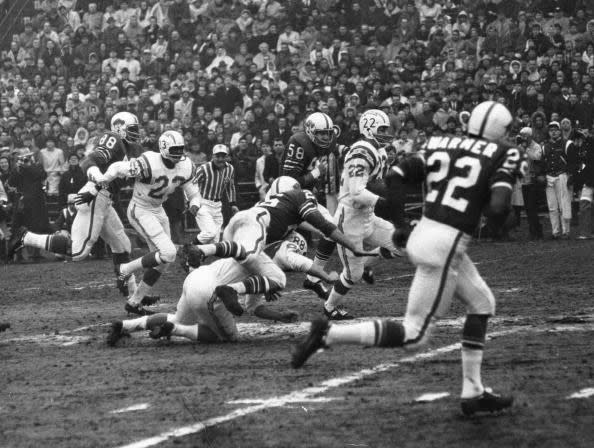

32. The Hit Heard 'Round the World

When the Bills’ Mike Stratton crushes Chargers halfback Keith Lincoln as he attempts to catch a pass in the left flat, it not only causes an easy incompletion, but also completely changes the momentum of the 1964 AFL Championship.

Leading and on their second possession of the game, the defending AFL champion Chargers seem in control until Stratton perfectly times his hit on Lincoln, drives his right shoulder into his ribs, and sends his helpless opponent to the frozen turf beneath them.

Lincoln, who is one of the top offensive threats for the Chargers, cracks three ribs, and the Bills hold on to the momentum and score 20 unanswered points.

“It was a definite game-changer that propelled the Bills to their first of two straight AFL titles,” says Ken Crippen, executive director of the Professional Football Researchers Association.

Related: The Best NFL Stadiums

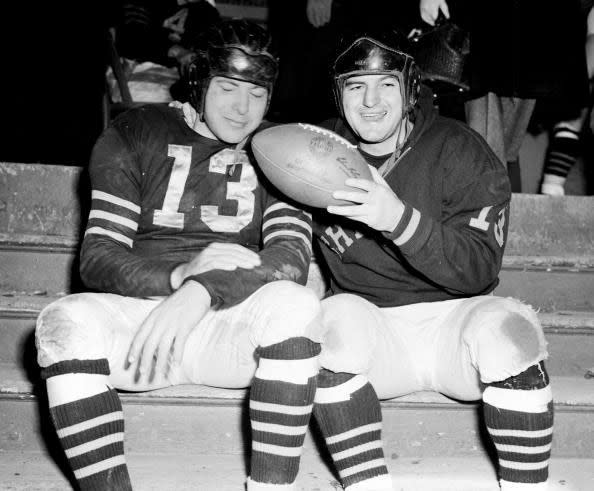

31. The Catch and Lateral

In the 1933 offseason, the NFL had separated into two divisions, and now the winners of each are facing off against each other in the league’s first championship game.

At Chicago’s Wrigley Field, the Bears and the Giants battle back and forth in a contest that sees several lead changes and more than its fair share of fireworks, but it’s the final trick play that decides the outcome.

Thinking on his feet, Chicago fullback Bronko Nagurski fakes a run and tosses a jump pass to Bill Hewitt for 14 yards, who then laterals to Bill Karr, who then runs 19 yards for the winning touchdown in the Bears’ 23-21 triumph.

“Plays were improvised a lot more back then,” says football historian Jim Gigglitoi. No kidding.

30. Broadway Joe Airs One Out

Joe Namath is still a week away from making his famous Super Bowl guarantee when he faces a tough Raiders team in the 1968 AFL Championship.

The Jets control most of the game, but an errant Namath pass is intercepted and leads to an Oakland touchdown and lead in the fourth quarter. Down by four points, Namath and wide receiver Don Maynard decide that if Oakland’s George Atkinson moves up to play bump-and-run, the Jets will take a chance deep.

And that’s exactly what the defensive back does.

As Namath’s pass sails through the air, Maynard hustles to get under it and makes an over-the-shoulder, Willie Mays-style catch down at the 6-yard-line.

The tandem hooks up again seconds later and gives the Jets their only AFL title.

ESPN anchor and host of Sunday NFL Countdown Chris Berman recalls, “That play put the Jets in the Super Bowl.”

29. Cromartie's Record Return

With four seconds remaining in the first half of their 2007 regular-season matchup, the Chargers and Vikings are deadlocked at 7.

With the ball resting at the San Diego 41, Vikings’ coach Brad Childress elects to send out kicker Ryan Longwell to attempt a 58-yard field goal. San Diego counters by positioning electrifying cornerback Antonio Cromartie in its end zone in hopes that Longwell’s kick will fall short.

And guess what? The strategy pays off when the field-goal try dips below the uprights and into the hands of a leaping Cromartie, who has to brace himself to avoid falling out the back of the end zone.

But rather than kneel down, Cromartie takes the ball out. He streaks down the sideline with a convoy of blockers, and high-steps into the end zone for the score.

“The Vikings went on to win this game, but Cromartie’s return at the end of the first half was the memorable moment,” says Jim Gigglioti. At 109 yards, “it’s the longest play of any kind in NFL history, and a mark guaranteed never to be broken.”

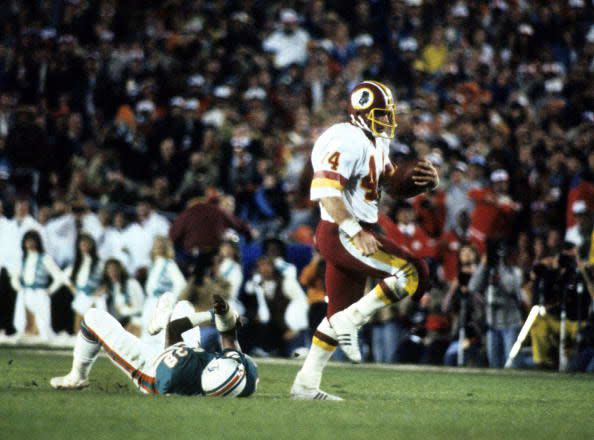

28. Run, Riggins, Run

With time running out on the Redskins in Super Bowl XVII, Washington faces a fourth-and-1 against a stout Miami defense. The Dolphins lead, 17-13, and the ball sits at Miami’s 42-yard line as the Redskins prepare to go for the first down.

After a nerve-wrenching timeout, quarterback Joe Theisman hands the ball to running back John Riggins, and the offensive and defensive lines converge.

Riggins dashes toward the left side of the line and the first-down marker, breaks through the tackle of a Miami defender, and outruns the rest of the defense on his way to the end zone.

“It was a play that captured the essence of the great Joe Gibbs teams,” says Ray Didinger, award-winning sportswriter and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, speaking about Washington’s coach.

“On fourth down, the ’Skins ran their Hall of Fame back off the left side behind the Hogs—their mighty o-line. Riggins broke one tackle and took it the distance.” The Redskins go on to win the game, 27-17.

27. The Rookie Arrives

Although Don Hutson will go on to catch an NFL-record 99 touchdown passes and will come to be known as the first “modern” NFL receiver, no one in Green Bay quite knows what to expect when the rookie from Alabama first takes the field in 1935.

The Packers are facing the Chicago Bears as Hutson splits out wide, standing on his own 17-yard line. As the ball is snapped, Hutson streaks down the field, blowing past the Bears secondary.

After hauling in a pass from QB Arnie Herber, Hutson blazes downfield for the only score of the game. “Green Bay purposely kept its prized rookie under wraps in the first game of 1935, saving him for the rival Bears the next week,” says Jim Gigglioti.

“On the first play against Chicago, Hutson announced his arrival as the NFL’s premier offensive threat.”

With Hutson’s catch, the dawn of the passing era begins, and pro football will never be the same.

26. The Miracle at the New Meadowlands

Down 31-10 to the New York Giants in the fourth quarter of a crucial December 2010 division matchup, the Philadelphia Eagles look lifeless, as if their hopes of winning the game—and the NFC East—have long vanished.

But in a remarkable 8-minute stretch, beleaguered quarterback Michael Vick plays like a man possessed, leading his Birds all the way back by passing for two quick scores and running for another.

The Giants are unable to answer the three touchdowns, and as a result, are prepared to take the game into overtime with 14 seconds left on the clock. All rookie punter Matt Dodge has to do is punt the ball out of bounds, and the game will end in regulation.

“Everybody knew that,” says Ken Crippen, executive director of the Professional Football Researchers Association. Except for Dodge, who fails to heed the message.

On a high snap, Dodge kicks a line-drive punt directly to electrifying Eagles return-man DeSean Jackson, who grabs the ball at his own 35, and immediately muffs the catch.

But Jackson quickly snatches it up and proceeds to zip up the field thanks to a devastating block by receiver Jason Avant.

As time expires on the clock, Jackson scurries into the end zone untouched. The only game-ending punt return in NFL history caps an astonishing comeback, shocks an entire New Meadowlands stadium, propels the Eagles to the unlikeliest of division titles, and sends Dodge to the unemployment line in the offseason.

“It just goes to show that you need to play a full 60 minutes of football,” Crippen says.

25. The Ghost to the Post

It’s third-and-long for the Raiders on their 44-yard line, trailing the Colts by a field goal with two minutes to play in the 1977 AFC playoffs. Oakland offensive coordinator Tom Flores calls a pass play, but instructs his quarterback to take a peek at the Ghost to the post.

Big tight end Dave “The Ghost” Casper lines up on the right side, set to run a post route downfield to the left upright.

Seeing that Baltimore’s coverage scheme will prevent Casper from reaching the left post as intended, Oakland quarterback Ken Stabler lofts the ball toward the right side of the end zone. Casper—who has already notched two touchdown catches in the game—finds the ball mid-air and adjusts his route and makes a twisting basket catch over his head while splitting two defenders.

His impressive catch sets up Oakland’s game-tying field goal, pushing the game into overtime. Stabler and Casper will again connect for the game-winning touchdown, advancing past Baltimore, 37-31.

“This was one of the most exciting NFL postseason games ever,” says Jim Gigglioti.

24. The Clock Play

The Dolphins, trailing the Jets, 24-6, with just a few minutes left in the third quarter of their 1994 regular-season meeting, are desperately trying to play catch-up.

And with Dan Marino at the helm of the Miami offense, both teams know anything is possible. Already renowned for his fourth-quarter comebacks, Marino throws two touchdown passes to bring the Dolphins within three points of the reeling Jets.

With just 30 seconds remaining in the game and the clock ticking, the ball rests on the Jets’ 8-yard line. Marino rushes to the line of scrimmage, and motions that he’s going to spike the ball to stop the clock.

Instead, he takes the snap and zips a pass toward a streaking Mark Ingram, who catches the ball in the front corner of the end zone ahead of a befuddled Jets defender.

“No one had ever attempted that,” says Herm Edwards, ESPN NFL analyst and former NFL head coach, of Marino’s fake spike. “It caught the defense off-guard because it was totally unexpected.”

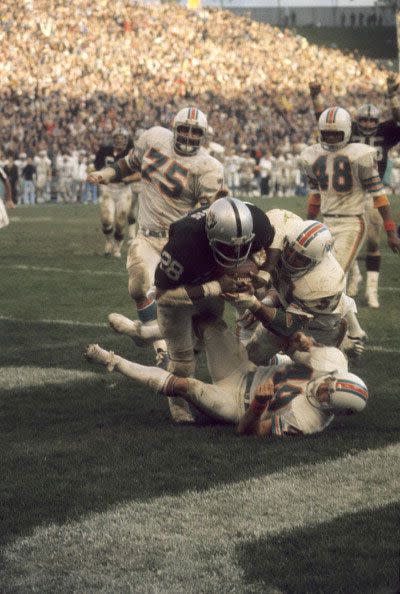

23. A Sea of Hands

The score between the Miami Dolphins and the Oakland Raiders has seesawed back and forth throughout most of their 1974 AFC playoff game. And now, with just two minutes to play, Miami leads, 26-21.

Oakland quarterback Ken Stabler knows his team has just one more shot to win the game and, after leading the Raiders down the field, the ball sits 8 yards from the end zone with just 35 seconds to play. On first and goal, Stabler rolls left, but is tripped up by a Dolphin defender.

As he falls to the turf, the Raiders quarterback floats a prayer toward wide receiver Clarence Davis, who is surrounded by Miami defenders in the end zone.

As Davis leaps for the ball, so do two Dolphins. All three players get their hands on the ball, but it’s Davis who manages to wrestle it away for the winning score.

“It was a miracle that Clarence Davis was able to make that catch surrounded by opposing players,” says Ken Crippen, executive director of the Professional Football Researchers Association.

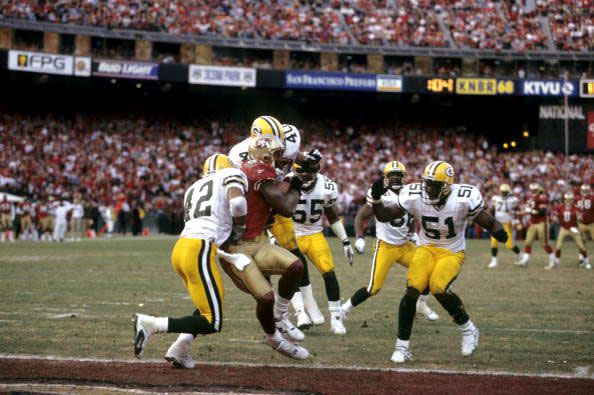

22. The Catch II

On January 3, 1998, the 49ers trail, 27-23, to the Packers, a team that has beaten them three straight times in the playoffs. Winning is a tall task, especially since the Niners must go 76 yards with less than two minutes in the game.

After driving to the Packers’ 25-yard line with only 8 seconds remaining, quarterback Steve Young croses up the Pack. Instead of throwing to all-time great Jerry Rice, he looks for his young receiver, Terrell Owens.

Young stumbles out of the pocket, recovers, and somehow finds Owens between several Green Bay defenders for the winning score.

“It was a seemingly impossible catch-and-throw that threaded the needle between a trio of Packers’ defenders,” says Jim Gigglioti. “In San Francisco, they immediately began calling it ‘The Catch II’,” he says.

21. Wide Right

Scott Norwood is sometimes compared to baseball’s Bill Buckner. Both are blamed for costing their teams a championship.

And while Buckner’s was the more egregious—the ball went through his legs—Norwood’s was never redeemed, as it marked the start of the Bills’ four-year run of Super Bowl defeats.

With just eight seconds remaining in Super Bowl XXV and the Bills trailing the Giants, 20-19, Buffalo head coach Marv Levy sends Norwood out to kick a 47-yard field goal.

Norwood had been 1-for-5 from 40-plus yards on natural grass that season. So while it shouldn’t be a major shock that Norwood pushes the ball wide right, he goes into history as the goat.

The Bills will never get closer to victory in any of their following three Super Bowls.

“One kick left a legacy for so many men,” says ESPN NFL Insider Adam Schefter. “But if that kick had just been slightly more accurate, the Bills would be discussed as one of the greatest teams in NFL history.”

Related: Why Your Favorite Sports Team Is Slowly Killing You

20. Payton's Crazy Call

As the second half of Super Bowl XLVI is about to get under way, the New Orleans Saints trail the Indianapolis Colts, 10-6. Most think Indianapolis is destined to win its second Super Bowl in four years, and Pro Bowl quarterback Peyton Manning is ready to lead his offense back onto the field.

New Orleans lines up in a normal kickoff formation, but coach Sean Payton has trickery on his mind.

The Saints successfully execute an onsides kick that catches the Colts completely off guard. The Saints go on to score on that drive, and eventually win the game, 31-17.

“It’s the gutsiest call in Super Bowl history,” says former NFL head coach and ESPN Monday Night Football analyst Jon Gruden.

“No one possibly expected them to do an onside kick to start the second half of the Super Bowl in a tight game. No way. The idea of doing that sounds good when you’re joking around with your buddies, but you just don’t do that.”

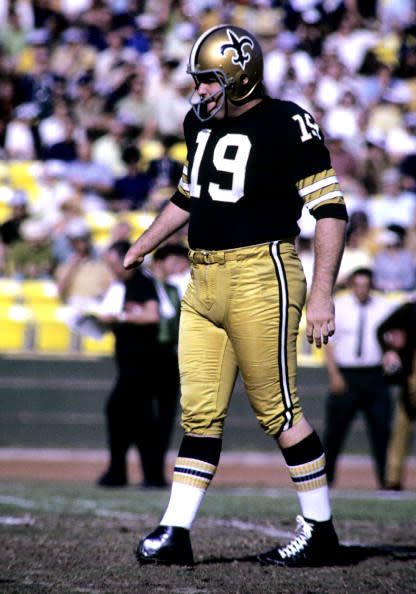

19. Dempsey Goes the Distance

With just two seconds left on the clock, the New Orleans Saints trail the Detroit Lions, 17-16, in front of a packed crowd at the Big Easy’s Tulane Stadium in 1970. The Saints call on their placekicker, Tom Dempsey, to win the game with what will be the longest completed field goal in NFL history—63 yards.

Dempsey is notorious for his clubbed kicking foot—a birth deformity that some say is an unfair advantage. But Dempsey has never attempted a field goal of this length.

The current record for the longest kick is 56 yards, but the tension in the air is palpable, as both teams and their fans know Dempsey is capable of miraculous things. As he steps forward and strikes the pigskin, everyone can tell Dempsey’s kick has a shot.

The ball spins end over end, and clears the goal post by mere inches. One referee jumps in the air as he signals that the record-smashing kick is good.

Though Dempsey’s record distance will be matched in the future, the Saints kicker is the first to reach the mark, “and he’s the only one to do it with half a kicking foot,” says Jim Buckley, editor of NFL Magazine.

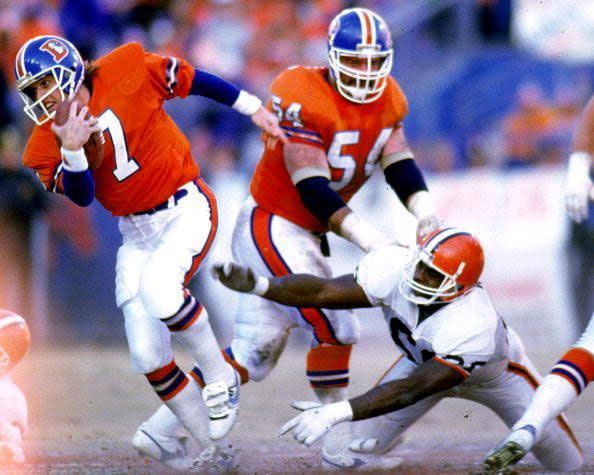

18. The Drive and John Elway

With just 5:02 left to play in the 1987 AFC Championship Game, the Denver Broncos trail the Cleveland Browns, 20-13. A young quarterback named John Elway is at the helm of the Denver offense, and is hoping to somehow drive his team 98 yards for the tying score.

Mixing in short passes, runs, and mid-range throws, Elway methodically marches the Broncos down the field, overcoming an 8-yard sack as he battles the dwindling game clock.

With just 39 seconds left to play, Elway hits Mark Jackson for a 5-yard touchdown pass, capping what is now referred to as The Drive.

“It’s what everyone thinks of now when they think of Elway,” says Ray Didinger, award-winning sportswriter and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The Broncos kick a field goal to win in overtime, and Elway cements his reputation as one of the game’s all-time clutch performers.

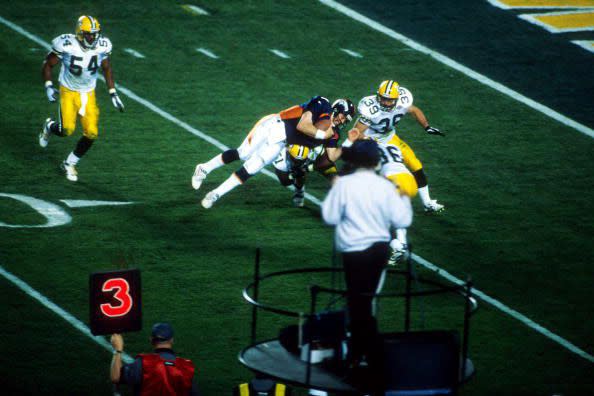

17. Elway's Dive

As legendary as he is for his otherworldly stats and clutch play in big games, Broncos quarterback John Elway has a chorus of doubters in 1997.

Why? Because he’s walked away from the three Super Bowls he’s played in without a ring.

With Denver facing dominant Green Bay in Super Bowl XXXII, the 37-year-old Elway is on his last legs—but he’s still got some fight left in him. Late in the third quarter of the game, with the score tied up at 17, Elway makes one of the gutsiest plays ever by a quarterback.

On third-and-6, Elway drops back and scans the field for an open receiver. None in sight, he takes off for the first by himself.

While 99 percent of NFL quarterbacks—especially ones in the twilight of their career—might slide in the situation, Elway knows that the only way he’ll get the first down is to dive. And he does—headfirst—while the three Green Bay defenders that hit him simultaneously spin him like a top.

Denver goes on to score a touchdown and, later, win the game. “John Elway’s spinning helicopter play in the Super Bowl exorcized all those demons of the past that he wasn’t able to win it all,” says Jon Gruden. “The reckless, gotta-have-it desire to be a champion put an exclamation point on Elway’s Hall-of-Fame career.”

Related: The Anarchy Workout—Get In the Best Shape of Your Life Starting TODAY!

16. Leon's Big Bowl Blunder

Far behind the Dallas Cowboys, 52-17, late in Super Bowl XXVII, the Buffalo Bills know their chances of victory are nill. But in an attempt to make the final score less onesided, the Bills elect to go for it on fourth-and-6 from the Cowboys’ 30-yard line.

After avoiding a few defenders, Buffalo quarterback Frank Reich is stripped on the play, and Dallas’s Pro Bowl defensive tackle Leon Lett scoops up the ball and rumbles toward the Buffalo end zone.

It appears that Lett will score easily, but just before he crosses the goal line, the Cowboy defenseman begins to dance and point toward the crowd.

The showboating and poor sportsmanship allows Bills wide receiver Don Beebe enough time to catch Lett and knock the ball away. The football rolls out of bounds in the end zone, resulting in a touchback for Buffalo on the 20-yard line.

For Beebe, “it’s an amazing example of an athlete never giving up, no matter what the odds or the score,” says Jim Buckley, editor of NFL Magazine. For Lett, it’s one of the most memorable blunders in Super Bowl history.

15. Harrison Runs Home

With just 17 seconds left in the first half of Super Bowl XLIII, the Arizona Cardinals are on the doorstep of the Pittsburgh Steelers’ end zone. The score is 10-7 in favor of the Steelers, and it’s first-and-goal from the 2-yard line as quarterback Kurt Warner takes the snap from a shotgun formation.

He tries to hit wide receiver Larry Fitzgerald on a slant route in the end zone, but fearsome Pittsburgh linebacker James Harrison steps in front of Fitzgerald and intercepts the pass.

With a convoy of blockers, Harrison starts bounding down the sideline toward Arizona’s end zone. Although Warner, Fitzgerald, and a handful of other Cardinals have a good shot at tackling the 242-pound Harrison, he manages to slip, bull, and juke his way past all of them and into the end zone as the half expires.

“It was the longest interception runback in Super Bowl history—and by a linebacker at that,” recalls Jarrett Bell, football writer for USA Today. “Sometimes, I think Harrison is still running.”

14. Swann's Super Catch

By the time the Steelers defeat the Cowboys in Super Bowl X, Lynn Swann’s MVP trophy is all but inevitable. The receiver hauls in four balls for 161 yards—including one that will resonate more than four decades later.

Late in the second quarter from Pittsburgh’s own 10, quarterback Terry Bradshaw hurls a 53-yard pass to Swann down the middle of the field.

Swann dives, juggles, and hauls in the pass while falling down with Cowboys cornerback Mark Washington holding on to him.

Even though the acrobatic grab ultimately has little to do with the outcome of Super Bowl X (the Steelers miss the ensuing field-goal try), it still shines as the best example of Swann’s dazzling athleticism.

“There’s not another player from my childhood that was replayed and imitated more in backyard football games,” says Adam Schefter, an ESPN reporter on the NFL.

“How many times was I or one of my childhood buddies diving for a football, juggling it and trying to pull it down the way Lynn Swann did?”

13. Vinatieri's Clutch Kick

In the final game at New England’s Foxboro Stadium, in a crucial AFC playoff matchup, all hope seems lost for the home team. It appears that Raiders cornerback Charles Woodson has forced a Tom Brady fumble to seal an Oakland victory.

But after much deliberation, officials cite the obscure “Tuck Rule” and determine that Brady didn’t fumble after all, but instead threw an incomplete pass.

The Pats subsequently drive into field-goal range with new life, and with less than a minute remaining in regulation, kicker Adam Vinatieri knocks home a 45-yard field goal on the snow- and ice-covered ground to tie the game, 13-13.

The Patriots win in overtime, and ultimately win the Super Bowl.

“Nobody has ever kicked a longer field goal in such miserable conditions,” says Adam Schefter. Adds his colleague Chris Berman: “It’s the single greatest kick in the history of football.”

Related: Why Tom Brady’s Diet Is Absurd

12. The Ice Bowl Sneak

It’s just a 1-yard touchdown. Nothing special. A wedge run to the right with a quarterback keeper. An absolutely ordinary play.

But on this day, on this field, it becomes a play that defines an entire organization.

It’s the 1967 NFL Championship Game at Lambeau Field to determine who will face the AFL champ in Super Bowl II.

In a game that will come to be called the Ice Bowl, the Packers and Cowboys battle each other and the elements to decide a winner. The thermometer reads 15 degrees below zero and the field is a frozen, slippery mess, but neither team backs down.

In a truly epic struggle, both teams battle back and forth until the game comes down to the Packers’ final drive. Green Bay successfully moves the ball all the way down to the Dallas 1-yard line and is promptly stuffed on two consecutive runs.

Facing third-and-goal, Packers quarterback Bart Starr calls his own number and follows his center and right guard into the end zone—and the record books. “Starr’s run in the Ice Bowl ended an era,” says Chris Berman, ESPN anchor and host of Sunday NFL Countdown.

“Yes, the Packers won the Super Bowl two weeks later, but it was the end of the Lombardi era. It punctuated everything they had done and stood for, and it was their fifth championship in seven years. That one-yard run was just so momentous because the next year Lombardi wasn’t there and the old guys were gone, and that was their last gasp.”

11. The Holy Roller

Since 1968, the Oakland Raiders haven’t lost to their divisional foe, the San Diego Chargers. But after finally breaking the streak in their second meeting of the 1977 season, the Chargers seem ready to start their own win streak as they lead the Raiders, 20-14, with just 10 seconds left on the clock during their first meeting of the ‘78 season.

Raiders quarterback Ken Stabler appears to have no options as several Charger defenders swarm him. But Stabler fumbles the football forward and out of immediate danger.

Another Raider manages to reach the ball first, and as the Chargers wrap him up, he too fumbles the football farther up the field . . . where a third Raider, Dave Casper, falls onto it in the end zone.

Oakland wins the game following its successful extra-point attempt.

“That play changed the way the game was officiated because you were no longer allowed to advance the ball to your own teammate on a fumble,” says former NFL head coach Jon Gruden.

10. Big Ben's Last-Ditch Dagger

It seems like the Cardinals’ night has finally arrived. One of only a handful of NFL franchises without a Super Bowl title, the 9-7 squad rides the “Kurt Warner to Larry Fitzgerald” wave all the way to a 23-20 lead with barely more than two minutes left in Super Bowl XLIII.

But Ben Roethlisberger is not to be denied.

The Steelers quarterback moves his team 72 yards down the field with relative ease before connecting with the evening’s hottest receiver, Santonio Holmes.

Holmes makes the touchdown grab on his tiptoes in the very back corner of Pittsburgh’s end zone, somehow landing both feet in bounds.

After a booth review, the call stands—and one of the most exciting Super Bowls ever comes to a dramatic conclusion.

“That was Ben Roethlisberger at his best. He made two or three insane scramble plays to put the Steelers in range. Then he stuck the dagger in ‘em,” says Jon Gruden.

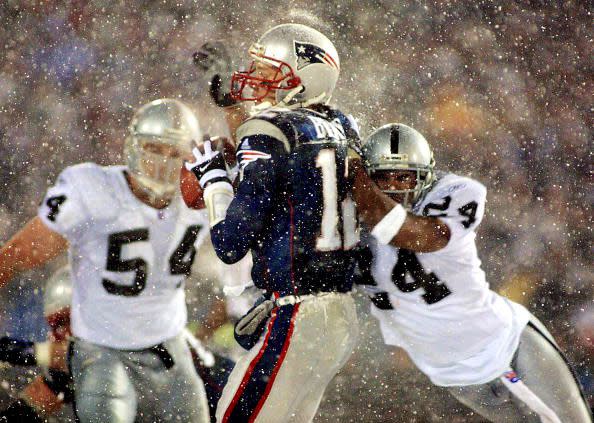

9. The Tuck Rule

On a snowy winter night in Foxborough, Massachusetts, referee Walt Coleman issues perhaps the most famous (or infamous) declaration of an incomplete pass in NFL history.

With less than two minutes remaining in the 2002 AFC Divisional Championship Game, Oakland holds a 13-10 lead over New England.

The Raiders seemingly seal their victory after hard-hitting cornerback Charles Woodson sacks Pats quarterback Tom Brady, causing a fumble that Oakland recovers.

But Coleman reviews the play and determines that Brady’s arm was moving forward into a “tuck,” which technically constitutes an incomplete pass.

The reversed call propels New England’s dynasty, which—a decade, four conference championships, and three Super Bowl championships later—continues today.

“Without it, the Raiders very well might have another Super Bowl title and the Patriots might not have launched the run that resulted in three Super Bowls,” says Adam Schefter, the NFL Insider for ESPN.

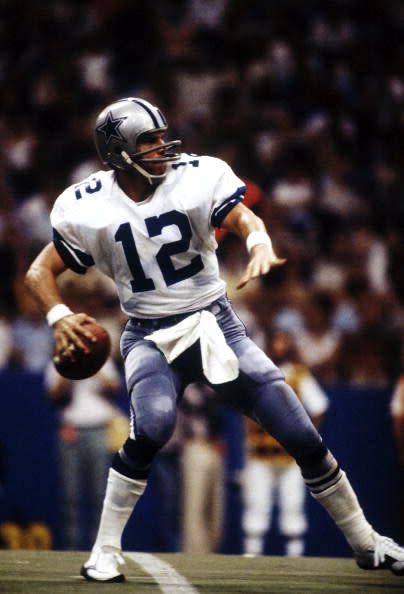

8. The Hail Mary

Trailing with next-to-no time left, Dallas quarterback Roger Staubach must save the Cowboys’ 1975 season in a divisional round playoff game against the Vikings.

So he turns to a higher power: Staubach throws the ball up in desperation toward his go-to receiver, Drew Pearson. Knocked to the ground, the quarterback can’t see Pearson haul in the catch for a miraculous, game-winning touchdown.

But his postgame reaction says it all: “I closed my eyes and said a Hail Mary,” he tells reporters.

With his holy admission, he coins a term that's now synonymous with big-time plays. “Staubach introduced ‘Hail Mary pass’ to the American lexicon,” says Ray Didinger, an award-winning sportswriter and member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

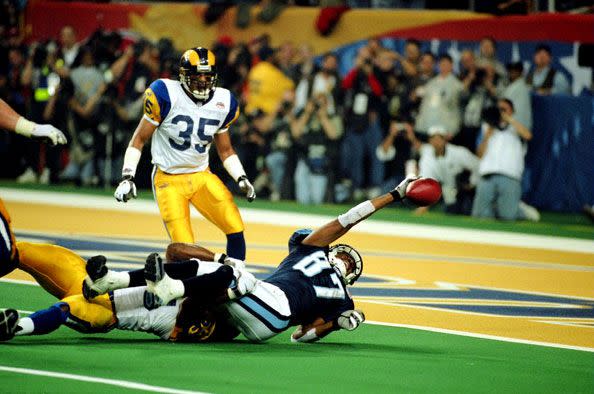

7. One Yard Short

With six seconds left on the clock in Super Bowl XXXIV, the Tennessee Titans have called their final timeout. The ball rests at the St. Louis Rams’ 10-yard line.

The Rams lead, 23-16, and Titans coach Jeff Fisher knows his team likely has only one shot at tying the game. “A couple of yards separated the Rams and Titans from a world title,” recounts Adam Schefter.

Hoping to lure the St. Louis defenders away from wide receiver Kevin Dyson, Tennessee sends tight end Frank Wycheck sprinting toward the back of the end zone. The ploy seems to work, and Titans quarterback Steve McNair hits a wide-open Dyson at the 5-yard line.

But, as Dyson makes the catch, Rams linebacker Mike Jones dashes up to hit Dyson near the 2-yard line. Dyson and Jones fall together while the wide receiver extends his right arm—and the football—toward the goal line.

The ball is less than a yard short as Dyson’s body hits the turf, and the clock—and the Titans’ title hopes—run out.

“It’s the single-most exciting last play of any Super Bowl,” Schefter says.

6. The Miracle at the Meadowlands

Two-thirds of the way into the 1978 season, the Eagles head to Giants Stadium at New Jersey’s Meadowlands Sports Complex to face their archrivals in an important division matchup.

The Giants take control of the game early on the strength of two touchdown passes by quarterback Joe Pisarcik. One of those passes burns Eagles cornerback Herm Edwards.

The Eagles rally, but trail, 17-12, with less than a minute to go in the game. With Philly out of timeouts, the Giants need simply to run out the clock.

As the TV audience at home watches the credits roll over the screen, Pisarcik takes the snap and botches a handoff to fullback Larry Csonka.

The ball hits the turf and Edwards picks it up on one hop at the Giant 27 and hustles all the way into the end zone with the game-winning score.

Says Edwards, now an ESPN NFL analyst: “That was nothing that you could ever draw up. When opportunity knocks, you better be ready. That time it just happened to be me, so I scooped up the ball and ran with it.”

5. The Horse Rides Home

The Baltimore Colts and New York Giants are in an epic struggle for the NFL Championship at Yankee Stadium in 1958. After trailing for most of the game, the Giants go up by three points early in the fourth quarter.

New York is able to keep Baltimore from scoring on its next two drives, and with just over two minutes to go, the G-Men need just one more first down to secure a victory. But Frank Gifford’s run is short and the Colts get the ball back, setting up a miraculous game-tying drive by Johnny Unitas.

What follows is the first sudden-death overtime game in pro football playoff history.

The Giants win the toss and get the ball, but the Colts hold them. Unitas and company pick up where they left off in regulation, picking apart New York’s defense. Facing a third-and-goal from the 1, Colts running back Alan “The Horse” Ameche gallops into the end zone for the win.

The thrilling finish earns the match the title of “The Greatest Game Ever Played,” and for good reason: Ameche’s run “put pro football on the map,” says ESPN’s Chris Berman.

“The game was never the same after that. It was on its way to becoming America’s most popular sport.”

4. The Music City Miracle

The first game of the 1999 playoffs sends the fifth-seeded Bills to Nashville to face the No. 4 Titans. Buffalo is completely outplayed in the first half, netting a paltry 20 yards of offense.

But Buffalo rights itself in the second half and, thanks to a Steve Christie 41-yard field goal with 16 seconds to play, appears poised to sneak out of Music City with a 16-15 victory.

Good downfield coverage on Christie’s ensuing kickoff will practically guarantee a win—but there are no guarantees in sports.

The kick is caught at the 25-yard line by Titans fullback Lorenzo Neal, who passes it off to tight end Frank Wychek. Wychek scampers to his right for a few steps before surprising everyone by planting his front foot and turning to throw the ball back across the field to wide receiver Kevin Dyson.

The throw is low, but Dyson scoops it up and rumbles down the sideline for the improbable game-winning touchdown. Many thought the throw from Wychek was an illegal forward pass, but referee Phil Luckett decides there isn’t enough evidence in the replay to overturn the ruling on the field.

The rest is history.

“I’ve seen that play attempted 1,000 times since, and it always ends up in futility. It may be one of the greatest executions of a desperation return in NFL history,” says Jon Gruden.

3. The Flee to Tyree

The 2007-2008 New England Patriots are perfect. After playing 18 games in 150 days, they have won them all.

All that’s left between them and the undisputed title as greatest team in NFL history is quarterback Eli Manning and the New York Giants, in Super Bowl XLII.

Unfortunately for New England, David Tyree’s helmet isn’t ready to anoint the team just yet.

Down 14-10 with 1:15 left in the game, the Giants have a crucial third-and-5 from their 44-yard line. Manning takes the snap, and the Patriots’ pass rush is on him immediately.

But Manning spins through and shirks off the tacklers, finding just enough time to chuck it up for Tyree, who is waiting 32 yards down the field.

A career special teamer, Tyree has caught just four passes all season. That doesn’t matter now, though, when he leaps for Manning’s ball alongside Patriots defender Rodney Harrison.

Tyree comes down with the ball, pinned improbably against his helmet, to keep the drive alive.

The rest is history: The Giants’ comeback culminates with a touchdown, and the Pats finish the season an imperfect 18-1—all thanks to Tyree’s classic catch.

“It was a remarkable example of determined resilience,” says Jarrett Bell, football writer for USA Today. ESPN’s Adam Schefter calls it “the greatest catch I’ve ever seen.”

Related: Eli Manning vs. The Haters

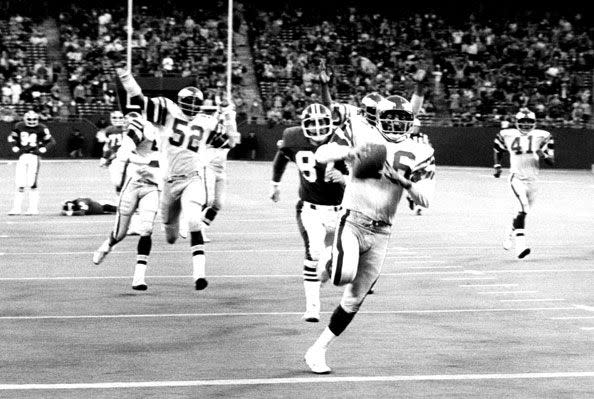

2. The Immaculate Reception

Trailing the Oakland Raiders, 7-6, with 22 seconds left in the 1972 AFC Divisional Playoff game, the hometown Pittsburgh Steelers face fourth-and-10.

Flushed from the pocket, Steelers quarterback Terry Bradshaw heaves a pass downfield toward John Fuqua. But intimidating Raiders safety Jack Tatum meets Fuqua as the ball arrives, popping the pigskin out of his hands.

While Oakland celebrates, Steelers rookie running back Franco Harris trails the play. At the Raiders’ 42-yard-line, he grasps the ball off his shoes—to some eyes, off the ground—and rumbles down the left sideline untouched for a score.

The Immaculate Reception, as the play will soon be called, will go on to be viewed more than the Zapruder film, thanks to pressing doubts about whether or not Harris actually catches the ball cleanly.

But make no mistake: The stunning grab kick-starts a Steelers dynasty.

“Harris’ catch is probably the greatest play in the history of pro football,” says ESPN's Chris Berman.

“The Steelers didn’t win the Super Bowl that year, but that was their first playoff win. This game put them on the map for four Super Bowls in six years. It was the start of something great in Pittsburgh for a franchise that had been horrible.”

1. The Catch

The drive that will lead to arguably the most memorable NFL play ever begins on San Francisco’s own 11-yard line.

Down 27-21 at home in the 1981 NFC Championship Game, the 49ers, led by coach Bill Walsh and a young quarterback named Joe Montana, hope to turn the page on more than a decade of futility.

Wedged in between the Niners and sweet victory, however, are 89 yards of grass—and the vaunted Dallas Cowboys, a.k.a. “America’s Team.”

The 49ers march methodically down the field, and stand huddling while the ball rests on the Dallas 6. It’s third down and 3 yards for a first down.

The play call? “Sprint right option,” remembers former NFL head coach and ESPN Monday Night Football analyst Jon Gruden. “Freddie Solomon’s covered and Dwight Clark’s working the end line. Joe Montana rolls right and makes one of the most clutch plays in NFL history.”

As Ed “Too Tall” Jones, the Cowboys’ 6-foot-9 defensive end, closes in on Montana, the quarterback pump-fakes, then sends the football sailing toward the back of the end zone.

The ball seems destined to end up in the bleachers, until the fingertips of Clark miraculously rise from a mass of defenders, securing the ball and a stunning San Fran victory.

The Niners squad rolls on to win that year’s Super Bowl and three more championships in the decade.

The Catch “was the turning point that created a dynasty,” says Jarrett Bell, football writer for USA Today.

Including the catch that created a dynasty.