'Blonde' Isn’t Mere 'Fictionalization' of Marilyn Monroe’s Life. It's Negligence.

Spoilers below.

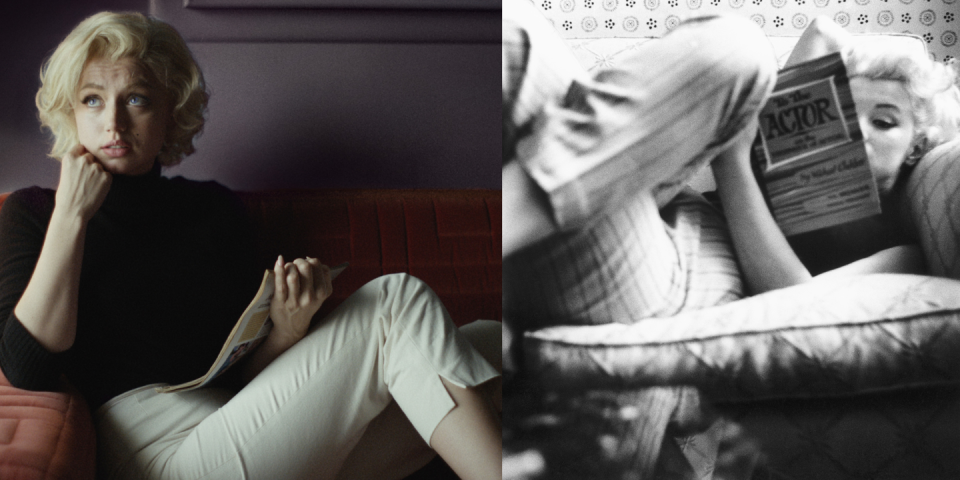

Imitation, a flattery, should not always be met with ire. Sometimes mimicry is powerful, even transcendent; this is occasionally the case with Ana de Armas’ all-consuming performance as Marilyn Monroe in Andrew Dominik’s much-derided new film, Blonde.

But it is in this power that a certain responsibility resides in the hands of the imitator—and, in this case, the one directing the imitator. To approximate a real person is to approach a sacred image; to twist and warp it is a risky calculation. To twist and warp it without empathy or precision? That’s negligence.

This is where the defense of Blonde as a “fictionalization” of Monroe’s life falls apart. The film, based on a very-much-fictional novel by Joyce Carol Oates, does not purport to be a biopic that traces the steps of Monroe’s biography with care. Instead it evokes the shroud of a tall tale, in order to justify whatever choices Dominik deemed appropriate for a singular interpretation of a singular star. Blonde’s status as fiction, by that measure, necessitates wild deviations and omissions from Monroe’s real life: The film includes multiple graphic scenes of rape, abortion, and oral sex; CGI close-ups of a talking fetus and a cervix pulled open via speculum; the gurgling sounds of a young girl nearly drowned in a bathtub; the inclusion of the words “baby,” “daddy,” and “slut” in claustrophobic proximity.

But to deny that Monroe was a tragic figure is to manufacture another fiction. The Gentlemen Prefer Blondes star’s story is uniquely, oppressively sad—many of the most widely recognized portions of her biography are indeed painful—and to ignore this in a film would be similarly negligent. But to deny Monroe most, if not all, of her joy, her wit, her friendships—not to mention the scraps of autonomy she wrested out of a white-knuckled industry—is an offense to Monroe and to the woman playing her. De Armas does the best she can to embody a real human being in Blonde’s more introspective moments: When given the opportunity, she soars within the film’s spellbinding cinematography and uncanny replications of real-life Monroe images. But there are too many scenes in which she’s asked merely to sob, to shrivel and bleed and vomit as she’s dragged and batted between set pieces, and so the image audiences are left with is one of Monroe as little more than a doll. How horrific, to be remembered only for one’s darkest moments, not a pinprick of hope cast over your corpse.

Alas, it is fiction. And fictionalization is fine, even effective, when audiences have the tools to discern between reality and fabrication. This is especially true when common knowledge of a figure is substantive enough to easily oppose a fictionalization. But all too often, audiences lack these tools; and in the case of Monroe in particular, the details of her life and death are already the subject of decades-spanning debate. Few, especially those of younger generations, might know the real Monroe beyond Andy Warhol’s famous portrait, or perhaps her much-discussed performance of “Happy Birthday, Mr. President.” (Especially after Kim Kardashian wore the late star’s dress to the Met Gala.) Therefore, an audience’s question when watching Blonde might not be, “What goals necessitated a narrative change from real-life events?” but instead, “Is this what really happened?”

It is also essential that fictionalization be intentional, and at times even deferential. It cannot be used as reasoning for exercising complete creative freedom over a real person’s life. Dominik has attempted multiple defenses for his treatment of Monroe in Blonde: In a viral interview with Sight and Sound writer Christina Newland, he argued the film represents “the feeling of being inside somebody’s anxious thought process,” that it’s “supposed to leave you shaking.” But perhaps most telling is when he says, “She killed herself. Now, to me, that’s the most important thing. It’s not the rest. It’s not the moments of strength.” (In a separate interview with Vanity Fair, he says, “There’s nothing sentimental here. Seeing the raw trauma in the film humanizes her.”)

But then he seems to contradict his own point (that witnessing Monroe’s trauma—and only her trauma—is “important”) by adding, “People who make films tend to think they’re incredibly important. But it’s just a movie about Marilyn Monroe.”

This is such a nihilistic perspective on the treatment of a person’s life that it seems manufactured to elicit rage. (And, on Twitter, it certainly did.) I have no issue with the provocative nature of Blonde, only in how it eschews humanity to be provocative.

Perhaps critic Bilge Ebiri was correct when he wrote, in his Vulture review of Blonde, that—because the film is fictional—“it’d be hard to come up with any biographic timeline from it. (And if one did, it’s likely be incorrect.)” Most accounts of Monroe’s life are incomplete, if not outright speculative. But it seems crass, in the wake of Blonde’s release on Netflix, not to address some of the questions about the real-life Monroe that a shaken audience might be left wrestling with. That seems, at the very least, a dignity she was not afforded in the film. Below, some of Blonde’s most pertinent plot questions—and how they compare to the real Norma Jeane Mortenson’s story.

Was Marilyn Monroe’s mother abusive?

The child known as Norma Jeane Mortenson was born to Gladys Pearl Baker nèe Monroe in 1926, in Los Angeles, California. She never knew her father, whom DNA testing later revealed to be the Consolidated Film Industries employee Charles Stanley Gifford, whom Baker had a relationship with while working as a film negative cutter.

Through much of her young life, Monroe lived in foster homes and orphanages, particularly after Baker suffered a mental break in 1934, was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, and was committed to a state hospital. (The circumstances around this breakdown were complex, but it seems likely that the loss of Baker’s son and grandfather in quick succession contributed to her mental state.) There is no concrete evidence that Baker abused Monroe in the manner depicted in the film (attempted drowning, etc.), but it is true that Baker was unstable and that her relationship with Monroe was forever one tinged with pain and abandonment.

It has also been reported that, during her time staying with family friends and foster parents Grace Goddard and Erwin “Doc” Goddard, a young Monroe was sexually abused. Film became Monroe’s escape, as she told Life in 1962: “Some of my foster families used to send me to the movies to get me out of the house, and there I’d sit all day and way into the night.”

Was Marilyn Monroe in a threesome?

In Blonde, Monroe engages in a threesome with Charlie “Cass” Chaplin Jr. and Edward “Eddy” G. Robinson Jr., a group which refers to themselves as “the Geminis.” Although these men both existed in Monroe’s real circle, the inclusion in Blonde serves mainly to elicit lurid fascination, and there’s no evidence Monroe participated in a similar threesome in reality. A brief affair between Chaplin Jr. and Monroe was rumored and discussed in both the biography Goddess: The Secret Lives of Marilyn Monroe and Chaplin Jr.’s own book, My Father, Charlie Chaplin, but there is no evidence that Monroe’s supposed relationship with Chaplin Jr. overlapped with a romance with Robinson Jr., and certainly not that the three participated in an affair together. (Nor was an alleged romance with Robinson Jr. ever confirmed.)

Did Marilyn Monroe have miscarriages?

Monroe’s troubled attempts to become a mother are well-documented, and it is true that she experienced multiple miscarriages and an ectopic pregnancy, likely due to her endometriosis. However, the miscarriage depicted in Blonde—in which she stumbles on the beach, falls on her stomach, and miscarries—is fictional.

Did Marilyn Monroe have abortions?

There is no confirmed report that Monroe had an abortion, let alone two abortions forced upon the non-consenting actress, as depicted in Blonde. It is, of course, very possible that Monroe might have actually chosen to undergo abortion procedures that went unreported; these procedures were commonplace enough in 1920-50s Hollywood that an anonymous actress referred to them as “our birth control,” per Vanity Fair.

During these years, Hollywood pregnancies—especially those experienced by bombshell actresses—were considered a detriment to studio profits, and therefore studios introduced “morality clauses” into their contracts with actresses. These clauses meant that pregnancies would violate studio policy, which in turn led to abortion becoming practically commonplace in Hollywood’s most storied halls.

As VF reported, “In the heyday of the Hollywood studio system, women were at their most desirable and their most powerful—but it still didn’t afford them the right to choose when it came to governing their bodies. Hollywood’s production codes extended to women’s reproduction.” It’s a shame that what was (and is) such a pertinent women’s rights issue in Hollywood is examined with such little nuance in Blonde.

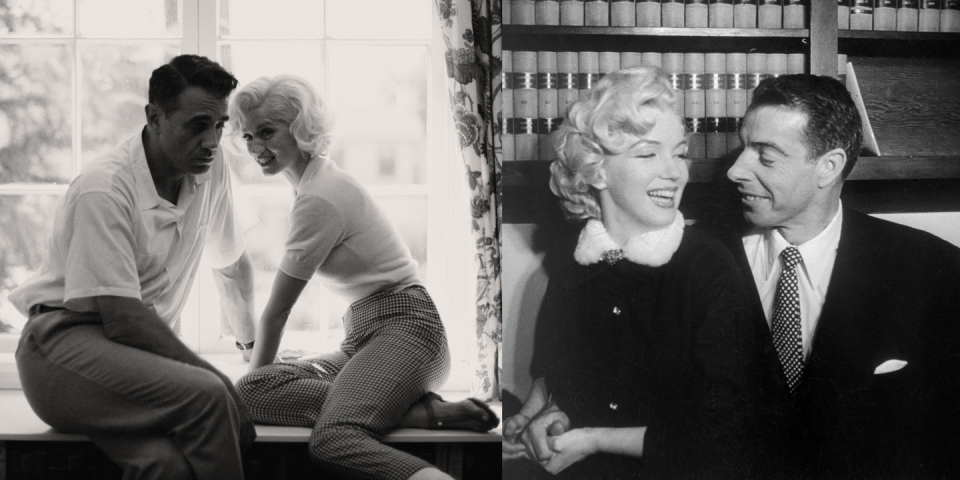

Did Marilyn Monroe’s husband, Joe DiMaggio, abuse her?

This is perhaps one of the areas where Blonde adheres most to fact, in that numerous reports confirm Monroe’s second husband, the baseball star Joe DiMaggio, was jealous and abusive. He disliked his wife’s image as a sex symbol for public consumption, but he also expected her to stop working and become a full-time housewife. According to Monroe’s friend and fellow actor Brad Dexter, she told him, “[DiMaggio] doesn’t want to know about my business. He doesn’t want to know about my work as an actress. He doesn’t want me to associate with any of my friends. He wants to cut me off completely from my whole world of motion pictures, friends, and creative people that I know."

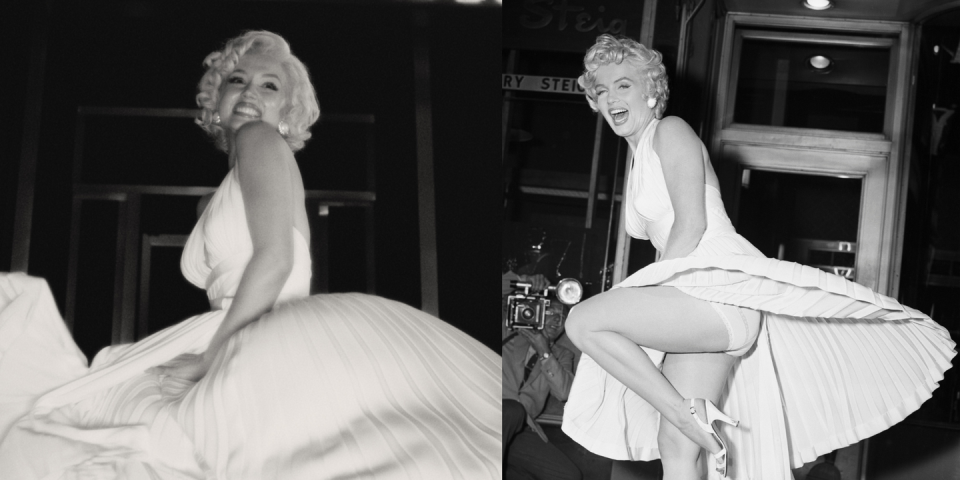

When she participated in a famous publicity stunt for her film The Seven Year Itch—in which Monroe stood above a subway grate for a several-hour photo shoot, attracting an audience of thousands—DiMaggio was livid, and within months the couple divorced.

What about her third husband, Arthur Miller?

Monroe met the famous playwright Arthur Miller in the early 1950s, but their relationship only became serious after Monroe’s divorce from DiMaggio was final and Miller had separated from his own wife. At the time, Miller was under investigation from the FBI for supposed ties to communism; he had been a vocal opponent of the Vietnam War as well as a supporter of civil rights. A 1951 FBI report identified Miller as an informant “under Community Party discipline” in the 1930s, according to The Associated Press, and a Party member in the 1940s. Miller denied this report, saying that in 1940 and again in 1947 he was “sufficiently close to Communist Party activities so that someone might honestly have thought that I had become a member.”

Regardless of the extent of Miller’s involvement, the attention—during the height of McCarthyism—led studios to urge Monroe to end her relationship with Miller. She refused, choosing instead to support Miller (an action that “helped to keep him out of prison,” per The Guardian), and so the FBI opened a file on her as well. The bureau ultimately found that “the subject’s views are very positively and concisely leftist; however, if she is being actively used by the Communist Party, it is not general knowledge among those working with the movement in Los Angeles.” The couple had a Jewish wedding ceremony, and Monroe converted to Judaism. They were captivated with each other’s minds; The Guardian reports that Miller saw Monroe “as a revolutionary idealist.”

Little to none of this is depicted in Blonde. What is depicted is Miller’s fascination with Monroe as a muse, her miscarriage—or at least a version of it—and his co-opting of her words and likeness for his writing.

Did Marilyn Monroe call men “daddy”?

Perhaps one of the most cringe-inducing narrative choices Blonde makes is the decision to have De Armas’ Monroe call every man in her life “daddy,” an on-the-nose allusion to her daddy issues. There is some reported truth to this depiction, however; the book Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life reports that Monroe called her first husband, James Dougherty, “Daddy,” and that DiMaggio signed his letters to Monroe as “Pa.” In Miller’s obituary, The Guardian similarly reports Monroe called her second husband “Papa.”

But Blonde extends this trend to other men, including her talent agent, suggesting that her childlike helplessness diminished her in the presence of any male in her orbit. Perhaps this choice would not have seemed so egregious, had Blonde depicted more than a couple incidents of her toe-to-toe sparring with studios, and had Blonde not entirely conjured the story of Chaplin Jr. posing as Monroe’s absent father.

Did Marilyn Monroe really receive letters from a man posing as her father?

In Blonde, Monroe receives letters throughout her career from her “Tearful Father,” claiming that he is watching from afar and that they will finally meet soon. Father and daughter never do meet, however, and it’s eventually revealed that Chaplin Jr. has been writing these letters to Monroe since the Geminis’s breakup. In a posthumous confession, he admits to Monroe that it was all a sick joke: There was never any “Tearful Father.” A distraught Monroe overdoses soon after.

There is no evidence that anything similar ever took place in Monroe’s real life. She was certainly plagued by abandonment issues—and so-called daddy issues—but Blonde’s treatment of these insecurities (both in the book and in the film) is particularly cruel.

Did Marilyn Monroe have a sexual relationship with President John F. Kennedy?

The exact nature of Monroe and President John F. Kennedy’s relationship remains the subject of feverish debate to this day. (Some conspiracy theorists posit that the actress’s overdose was orchestrated by the Kennedy family as a cover-up for her involvement with JFK; his brother, Robert; or both). This article won’t concern itself with all the details of these allegations, but suffice to say that plenty believed the two had a romantic relationship. And yet the likelihood that it played out in such a demeaning manner as depicted in Blonde—Monroe is referred to as a “dirty slut” while she performs forced oral sex—is low.

Although such an encounter was never confirmed outright, the biographer Donald Spoto wrote in Marilyn Monroe: The Biography that the couple shared one weekend together at Bing Crosby’s Palm Springs home in March 1962, and that Monroe had no desire to continue the relationship beyond that. As Susan Strasberg—friend of Monroe’s and daughter of her acting coach, Lee Strasberg—said, according to Spoto, “Not in her worst nightmare would Marilyn have wanted to be with JFK on any permanent basis. It was okay for one night to sleep with a charismatic president—and she loved the secrecy and drama of it. But he certainly wasn’t the kind of man she wanted for life, and she was very clear to us about this.”

Did Marilyn Monroe abuse pills?

This much, as depicted in Blonde, is true: During the course of her career, Monroe became addicted to prescription drugs, which she often took with alcohol. (She struggled with numerous ailments, including insomnia, anxiety, endometriosis, gallstones and depression.) She overdosed multiple times in her life, including the final overdose that led to her death.

How did Marilyn Monroe die?

On August 5, 1962, Monroe was discovered unconscious in her Brentwood, Los Angeles, bedroom. She was 36, found with her hand outstretched to her telephone and multiple empty prescription bottles next to her bed. Her death was ruled a probable suicide due to the number of drugs discovered in her system.

What of Marilyn Monroe’s life is left out of Blonde?

So much. We barely get to watch her impressive career play out, nor her devotion to the craft of acting—only the moments in which she decries “Marilyn Monroe” as a fiction. We never see her first marriage to James Dougherty at the age of 16, nor her relationships with numerous friends and co-stars, particularly female ones including actress Jane Russell and mentor Natasha Lytess. Blonde includes no mention of the film production company Monroe founded in 1954, nor does it acknowledge the ways in which Monroe crafted and executed her own image. It depicts her mental health issues—and eventual suicide—as “the most important thing” about her, as Dominik revealed in interviews, therefore condemning her as the eternal victim. No one can deny Monroe was a victim, at numerous times and in numerous ways. But to suggest she was never anything more is itself a fiction.

“I think that, when you are famous, every weakness is exaggerated,” Monroe told Life, mere days before her death. “This industry should behave like a mother whose child has just run out in front of a car. But instead of clasping the child to them, they start punishing the child.” Blonde is the punishment of a negligent parent, dragging Monroe’s image through all her real-life horrors (and several fabricated ones) in the name of an abstract truth Dominik seeks but never realizes in his film. “Woman, traumatized” is far from a new genre, but nor is it one automatically condemned to mistreat its subjects. Monroe, as in life, deserved a kinder touch. But as Marilyn: The Passion and the Paradox author Lois Banner wrote, “In the case of Marilyn, people believe what they want to believe.”

You Might Also Like