At Eternity’s Gate review: Willem Dafoe’s overdone van Gogh biopic is as mad as the man himself

Dir: Julian Schnabel. Cast: Willem Dafoe, Rupert Friend, Oscar Isaac, Mads Mikkelsen, Mathieu Amalric, Emmanuelle Seigner. 12A cert, 111 min

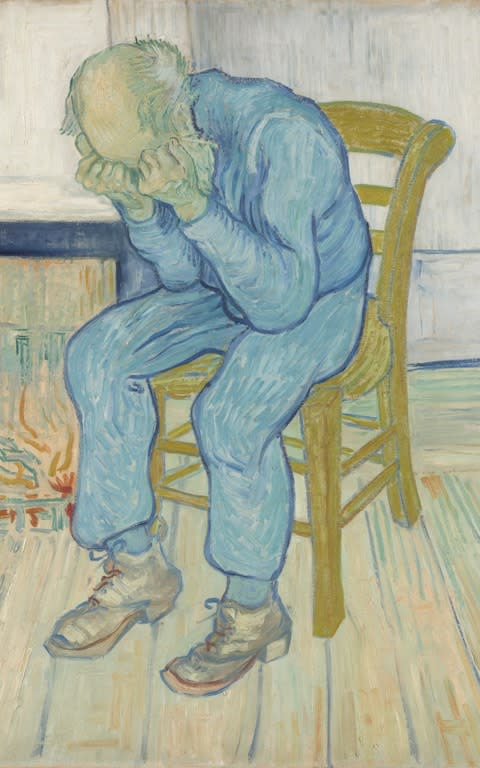

When one artist examines their debt to another, it can pay dividends – sometimes. In At Eternity’s Gate, the painter and filmmaker Julian Schnabel has Vincent van Gogh in his sights, and the film is full of thrusting, headlong artistry, as if trying to collapse any meaningful distance between portraiture and subject.

Early in the picture, Vincent (Willem Dafoe) is seen sprinting towards a sunset in an empty field near Arles, while the camera – manned by veteran French cinematographer Beno?t Delhomme – wobbles right up behind him. There’s no sound except for a dissonant piano score, as Vincent lies down at dusk and sprinkles soil between his fingers, letting it fall on his face with an expression of rapt concentration. Is this incipient madness? Genius? Both? It’s too soon to say.

There are all sorts of questions the film could ask about van Gogh’s mental state in this fruitful twilight of his life. Schnabel roughly begins with an exhibition in 1887, inside a cramped restaurant in Montmartre, where Vincent exhibited alongside a number of other artists and first met Paul Gauguin (Oscar Isaac).

For the next three years, beset by worsening inner torment, he withdrew to Arles, where Gauguin visited at the behest of Vincent’s brother and financial supporter Theo (a worried Rupert Friend). The two painters argue passionately about the state of their art as they walk along sunkissed hilltops, or consult in a gloomy brasserie.

This is all standard fare for van Gogh biopics, going all the way back to Vincente Minnelli’s resplendent Lust for Life (1956), for which Kirk Douglas earned an Oscar nomination – just as Dafoe did for this film. The forceful melodrama of that earlier portrait makes it easy for Schnabel to disdain; “I used to love it as a child, but it’s got every cliché”, he says, calling it “kind of the opposite of the film we have made”. This is exactly the hauteur that infects his film from top to bottom.

Schnabel wants to hoist himself above your usual biopic, right up to van Gogh’s creative plane, by using Delhomme’s camera in a splashy, intuitive way as if it were one of Vincent’s paintbrushes. It dives in for a blurry close-up here, or whip-pans back and forth. But the confusion of the two media creates a mess. We’re eternally aware of what the camera is doing, because Delhomme has been encouraged to throw all considered technique in the bin.

“The painters I like all paint fast, in one clear stroke,” van Gogh says in voiceover, as if to justify the aesthetic that Schabel wants. But a riposte from dissatisfied Gauguin, looking at a portrait of Vincent’s landlady (Emmanuelle Seigner), is more revealing. “You paint fast and then you overpaint – the surface looks like it’s made out of clay. It’s more like sculpture than painting…”

Schnabel overpaints. His clotted method gives us no clear view of van Gogh and a rather befuddled appreciation of what Dafoe – a striking physical match for the artist – is trying to do, because his acting has to compete with all the “spontaneous” friskiness on screen. Delhomme, for instance, uses a split diopter to blur the bottom of the frame when we see things from Vincent’s point of view, an effect Schnabel wanted to reconstruct after he tried on a pair of faulty bifocal glasses. It’s a madly arbitrary way to represent the man’s fracturing psyche.

Wary, presumably, of doing a Minnelli by showing van Gogh cutting his ear off, Schnabel skips right past that legendary event to the bandaged aftermath. The film becomes a series of tête-à-têtes in tight close-up – with “docteur Rey” (Vladimir Consigny); a priest (Mads Mikkelsen); a tattooed madman in an asylum (Niels Arestrup); the physician Paul Gachet (Mathieu Amalric). There’s something of the therapy session or confession booth about these scenes.

Dafoe, much more affecting in The Florida Project, does strain thoughtfully to make sense of van Gogh’s existential pain, and at least the shot/reverse-shot editing forces the camera to settle down. But everyone’s fighting a script, credited in part to Bu?uel’s great collaborator Jean-Claude Carrière, that is chronologically antsy to an alienating degree. Characters start conversations in French – not Dafoe’s forte, I’m afraid – then switch to strangely stilted English in a variety of accents.

The more the film speaks, the less it says, wandering with an ever-wider bifocal blur towards the Proven?al horizon. Van Gogh manhandles a peasant woman so that he can sketch her in a particular pose, and Mikkelsen, in a scene of deadly flat-footedness, asks him if he ever molested a child, and if he’s a painter (!) and why he thinks he is given he has such “unpleasant” work to show for it. (Vincent’s response is to compare himself with Jesus, and the priest with Pontius Pilate.)

The nadir comes with van Gogh and Gauguin bromantically urinating side-by-side into a radiant valley, while they pick apart the Impressionists. “I still think Monet’s pretty good?”, Dafoe wavers, the accent never less of a friend to him. The point with van Gogh is that he produced mind-boggling art while stricken with doubt that he’d failed all his life. This film is his spiritual antithesis – so recklessly confident that it paints right over him.