My French expat dream was sullied by villainous locals

For me being an expat was always about finding somewhere to call home, that elusive thing I lost when my mother died. This was compounded when dad – who remarried a few months later – sold the house I grew up in and moved overseas.

With its rain-weeping skies, gastro pubs and endless reruns of Benny Hill on TV, the UK wasn’t ‘it’. Nor – however much I loved it – was The Netherlands, that windmill-spiked country with its salty dropjes sweets, pancake-flat polders and straight-talking (sometimes to the point of rudeness) inhabitants where my Dutch mother grew up.

A few years after mum died, I fell for a Frenchman while on holiday in Crete and moved to Versailles. In the 90s, the famous chateau town was so dull that – as they say in French slang – ca puait le moisi (it stank of mould). Seeking a new life, we moved out of my partner’s cosy heated apartment in a bouji part of town and into his family’s holiday home in the rural backwaters of southwest France.

It was a centuries-old coaching house where we slid on socks across wooden floors so ancient they shone like cobbles, huddled around a cavernous fireplace whose flames threw strange shadows on the huge oak rafters high overhead, and slept snug on a straw-stuffed mattress in a lit bateau – boat bed – shaped like a giant Dutch clog.

Having left our jobs – his at the Palace of Versailles, mine in stand-up comedy – we had no income and lived on a diet of tomatoes served up in salads, soups and flans, supplemented by pails of fresh milk from the local farmer’s cinnamon-coloured Charentais cows.

It was so warm we swam most days in icy rivers and sunbathed beneath cornflower-blue skies. When the first snows fell in early January, kindly neighbours – who’d known my partner since he was in nappies – gave us cabbages and potatoes from frozen gardens, and we kept the home fires burning with rotten tree trunks that we dragged back from the surrounding woods and carved up with a blunt-toothed hand saw.

During the long winter months huddled by the smoking log fire we applied for one of the grants that were being handed out to people who were foolhardy enough to want to set up a business in rural France. Against all odds – and after negotiating an inordinate amount of red tape – we were awarded one to create a chambres d’hotes (guesthouse), which allowed us to get a loan to buy – and convert – a sprawling 20-room farmhouse next to a shallow river shaded by weeping willows in a neighbouring village.

To furnish our guesthouse we attended auctions in the neighbouring town of Angouleme. With lino and formica all the rage in rural France at the time we were able to buy sturdy walnut beds, ornate mahogany cupboards – and an oak farm table big enough to seat 20 people – for centimes. “What do you want with that old rubbish?” our neighbours would cry as we returned with our latest buys.

Their incomprehension didn’t stop there. In a village of 300 inhabitants – most of whom were in their 70s – two 20-somethings opening a business and hoping to attract tourists was incomprehensible. “But there’s nothing to do here,” they’d say as we endeavoured to explain the charms of long hikes in the forest, swimming in fern-fringed lakes, and then returning to lazy meals beside a flickering log fire in the minds of jaded city dwellers.

Shortly before opening for business we decided to clear the jungle-like undergrowth covering the opposite bank of the river, only to discover a boa constrictor-sized pipe leaking raw sewage beneath.

Our efforts to fix the problem led to a run-in with the local mayor. “Townies coming here to change things,” he roared when we tried to broach the issue. He made it clear that, as far as he was concerned, a couple of articulate “foreigners” could only spell trouble – they had to leave.

A few years earlier I’d read about how Formula One driver Alain Prost had been forced to flee his home near Saint Etienne and move to Switzerland in the 1980s after an angry mob of Renault workers came to his home and burnt his Mercedes, a response to his ongoing spat with Rene Arnoux, one of France’s most popular drivers. At the time I’d found the tale hard to believe. That changed when the harassment began – people staring and whispering when we entered the local shops; an elderly farmer spitting at us on a crowded street; kids, urged on by parents and grandparents, throwing stones at our dog (and, on several occasions, us).

It wasn’t all doom and gloom. Our guests, who came from as far afield as Buenos Aires and Los Angeles, loved the guesthouse and – thanks to the clever use of plants, perfume and masking tape – remained blissfully unaware of our battle to stem the village’s faecal tide. When not working, we spent hours in the woods foraging for mushrooms or gathering chestnuts; we kept chickens and ducks, and there were long summers when we swam in the nearby lakes and picnicked in the gloom of abandoned churches.

There was also plenty of light entertainment provided by a kooky Belgian pop star – famed for singing her (only) hit song on live TV dressed in a negligée whilst eight months pregnant – who bought and renovated the large stone house next door. After hiring and firing several architects she decided to work to her own plans. When the house was finally finished and the shutters and doors painted Barbie pink, she decided she wanted a wine cellar under the bedroom. A few days after digging commenced there was a boom like a bomb exploding. When we ran out into the street it was filled with rubble from the house which had collapsed, luckily without her in it.

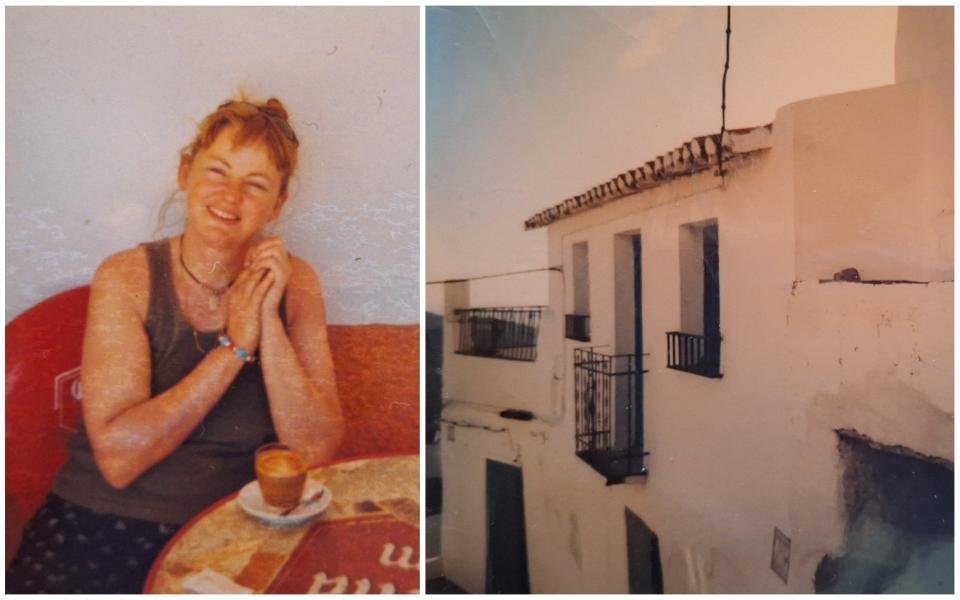

We stuck it out in La Charente for seven years and then, still seeking a place to call home (along with a lot more sunshine) we sold up for a good price and moved to a mountain village near Velez Malaga in southern Spain.

We loved almost everything about Andalusia – the music, the heat, the brine-fresh seafood tapas. The only problem was noise. Because, as we soon learnt, Andalusians never sleep. Whenever we returned to our charming casa along one of the pueblo blanco’s narrow streets – whether it was dawn or midnight – there would be children playing football, elderly neighbours having a good old chinwag and mopeds with souped-up exhausts farting over the cobbles.

Reluctantly, after six happy but exhausting years we sold up and bought a plot of building land in a remote spot higher up the mountain. By the time we’d got the foundations in, however, our peaceful plot with panoramic sea views was surrounded by illegal buildings that would soon be our only view. When we sold up this time, we took time out from our relationship and I spent several years hopping between countries – working for a newspaper in Cambodia; training to be a gaucho in Argentina; learning about ayurveda in Kerala – and still seeking that elusive place I could call home.

Together again in 2011 we decided to return to Crete. After travelling around the island for several months we stumbled across an old stone house surrounded by citrus groves and olive trees. It was the home I’d always dreamt of.

After 15 years here we speak Greek, make our own olive oil and have lovely neighbours who regularly invite us around for meals of vlita (wild greens) pies, xochloi snails and other meze snacks. From March to mid-December we swim from near-deserted beaches or have dinner up on the roof terrace watching the griffon vultures returning from foraging in the surrounding mountains.

These days when I return to the UK it’s like visiting a foreign country, and I do all the touristy things: searching for overpriced tat in Camden Market; paying an arm and a leg to ride The Eye. Last month, for the first time in my life, I even slogged up 334 steps to visit Big Ben.

Friends often ask if I miss anything from back home. In the words of Edith Piaf I reply, “Non, je ne regrette rien”, although I do have the occasional craving for bacon cooked properly and a greasy bag of fish and chips.