While traveling abroad, this woman needed an emergency hysterectomy

When people hear that I gave up my home to travel the world and work remotely for five years, they think I’m either nuts or “living the dream.” The truth is somewhere in the middle.

But romantic as that choice might seem, life doesn’t just stop when you decide to explore the world. Money problems, health issues, personal strife — they happen to us all, no matter where we go. When I began my journey abroad in 2015, at the age of 42, I prepared for some worst-case scenarios. One of those was the potential for health issues — but I also figured that was what insurance was for.

My first two years abroad were not struggle-free, but my health held steady. My father died just before my first anniversary as a nomad, and when that happened, I went home to Canada for a visit. While home, I took the opportunity to visit my gynecologist for a complete physical — just to make sure I was healthy before I headed back into the world. My mother had died of uterine cancer years before, and I was always extra-cautious about my gynecological health.

The timing was poor, and my internal exam couldn’t be completed. After five dry months, I had my period before leaving home. My doctor and I discussed my bloodless months, but we both thought nothing of it — stress and travel can disrupt flows. But as I resumed traveling in Europe and the weeks and months wore on, my period didn’t stop. Light spotting hounded me as I moved through the Czech Republic and Hungary, and into Greece.

My second-to-last night in Greece brought extremely heavy bleeding. The next day was my last before heading to Africa for a month in Morocco. I consulted a pharmacist and told them about my travel plans, and they insisted I visit an Athens ER. This was the last thing I wanted to do, but I thought of my mother and her illness, and knew I needed to go to the hospital.

After eight hours of testing, I was told that I’d need an outpatient procedure called an endometrial ablation. The doctor who saw me suggested that I could stave off bleeding during Morocco with progesterone tablets, then return for the ablation, which had a four-day recovery period. I took the pills and headed to pack for my flight.

Morocco began uneventfully, but I felt awful. Three weeks in, things climaxed with a terrifying night of blood loss. I went through a whole pack of pads in one night, changing them every 30 minutes. Was I hemorrhaging internally? It wasn’t just heavy bleeding, it was a horror show.

The next morning, I sobbed while telling my German innkeeper of my terrifying night. She and her housekeeper headed out to pharmacies on my behalf and brought back copious thick pads and more progesterone. I was popping the pills I’d gotten in Greece like candy, and they’d begun to work. My flow finally became somewhat manageable.

But my fear intensified. The bloody horror show suggested that I had been misdiagnosed in Athens, and my thoughts once again circled back to my mother and the uterine cancer that had killed her. A doctor in Canada had once told me that because of my genetics, I had a high risk of developing uterine cancer myself. What if that was what was going on? What if I required far more than an outpatient visit?

I sat in my Moroccan inn thinking over the options. Returning to Canada was out. The 12-hour flight, the likely wait of weeks for a diagnosis and then potentially months for surgery, the many thousands it would cost me to fly there and then rent a home in which to recover — it seemed easier and more affordable to find a solution abroad, where the cost of living was far lower.

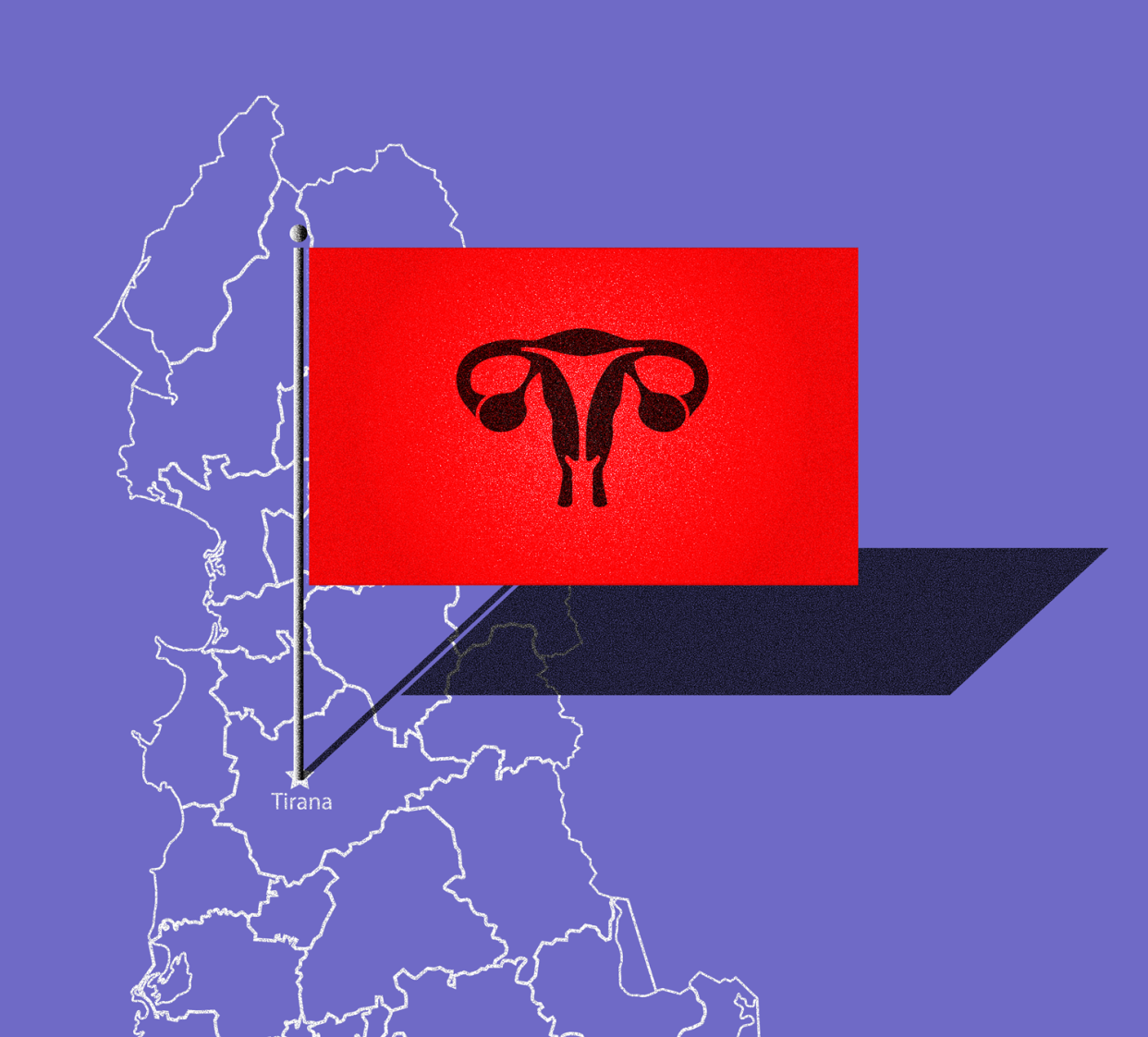

I began researching gynecological services throughout Europe, from Scotland to Croatia to Hungary. Ten days later I boarded a flight for Albania, to visit a private but budget-friendly American-style hospital. It was scary, and I was going in blind. But it felt like my best option.

As soon as I arrived in Albania, all of my fear disappeared. The Albanian hospital was a model of efficiency. Within 96 hours of landing, I had a battery of tests and went under the knife for a hysterectomy — more than 5,800 miles from my former life in Vancouver.

It was Dr. Zef who broke the news to me that a hysterectomy was needed. He understood English very well but was too proud to bungle his words, so he’d speak Albanian to his nurse, and she’d translate. When I started sobbing about my mother and my associated cancer risks, Dr. Zef stood up, rounded his desk, and squeezed me like a grandfather would. Shushing me, he wiped my tears away.

“Is OK, all be OK,” he promised, before chuckling affectionately and squeezing my cheeks. His warm smile and sparkling eyes have stayed in my memory — I’ve never had such a kind face console me in a moment of need. My fear dissipated. The world needs more cheek-pinching mirthful surgeons.

I thought surgery day would terrify me, but waking that morning, knowing that surgery was critical, I found strength. I was exhausted and in pain. I reflected on the days before my mother’s hysterectomy. She seemed so resigned and cool. Now I understood why.

Hysterectomy surgery is routine, but much can go awry. In the year since my surgery, a friend’s hysterectomy required an emergency bowel resection soon after. And, of course, it was my mom’s “routine” hysterectomy that revealed her cancer. She was dead six months later.

The hysterectomy itself, though, is almost easy. It’s recovery that’s hard, it’s recovery when things can go wrong. For eight weeks after surgery, extreme caution is needed when lifting things. For the first four weeks, it’s advisable to lift only three to eight pounds at a time. This was not conducive to my solo nomadic life, which regularly required carrying around a 50-pound duffle bag.

I couldn’t just agree to surgery; I needed a recovery plan. We delayed surgery for 72 hours so I could prepare for my weeks ahead.

Despite terrific abdominal pain, I got an Airbnb sorted out so that life in my makeshift home could be lifting-free — anything I needed would be at waist height. I cooked and filled my freezer with soups that Dr. Zef insisted would be best for recovery. I stocked up on everything from toilet paper to bread and coffee.

In a stroke of luck, my Airbnb host’s stepmother had been a surgical recovery nurse for 25 years. I hired her to visit me twice daily for the first week. She brought prescriptions and fruit, checked my incision for infection, and helped me clean my dressing.

For the weeks of my recovery, Tirana, Albania, was my home. Initially, it was a cheap surgery destination filled with ugly communist-era construction and decaying roads. But by the end of my stay, it had stolen my heart.

Tirana taught me that kindness transcends language. It convinced me that old-world medicine should go hand-in-hand with modern practices. It taught me that we only learn how strong we are when life forces our hand.

And it taught me about besa, a code of honor centuries old that Albanians live by even today. Basically, friend or foe, when you’re an Albanian’s guest, they will die to protect you. What better place to recover from surgery?

Nearly a year later, leaving my uterus in Albania has made my travels better — and obviously my health better too. Having a hysterectomy in Albania was never a part of my life plan, but it is what happened. And it reinforced my faith in myself and in the kindness of strangers. It also taught me that home can be found in the most unexpected of places.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.