The History of Bouillon Cubes

How colonialism and convenience made bouillon cubes a popular ingredient in kitchens around the world.

"Every home kitchen, every abuelita uses bouillon," says Mexican-American chef Edgar Rico of Nixta Tacqueria in Austin, Texas. "Just like you would find dried chile, avocados, onion, and garlic inside a pantry, bouillon cubes are in both my grandmothers’ pantries. It’s always the Knorr brand, the little baby cubes."

In Mexico, like much of Latin America, Knorr's "caldo con sabor de pollo" is the preferred brand of bouillon, easily spotted thanks to its iconic yellow-and-green packaging with a chicken on the front. Rico's grandmother uses it for mole, braised pork with chile verde, and soups.

Elsewhere in the world, other brands of bouillon may reign supreme, and their products may instead be labeled "stock cubes" or "broth cubes," but oftentimes the MSG-heavy concentrate is no less a pantry staple. Thanks to its relatively low cost, ease and speed of use, and intense flavor, bouillon is a popular ingredient in kitchens on virtually every continent, where powders and cubes are used to season soups and stews, and in some cases, are even sprinkled directly over cooked plates of food.

The Timeless Practicality of Broths and Soups

To understand how bouillon achieved such international popularity, you have to consider the central role that broths and stocks have played in human history. Using water to stretch ingredients into a full, and filling, nutritious meal is a survival-based innovation that has come to define culinary traditions around the world. In Japan, the term for a classic teishoku meal, ichiju-sansai, literally translates to "one soup, three sides." Elsewhere, soup is an essential side dish, like the small bowl of broth always served with Hainanese chicken or Thailand’s khao man gai. And while soup is more commonly a lunch or dinner in some countries, it's also still a common morning meal in many others: pho in Vietnam, menudo in Mexico, and lablabi in Tunisia to name just a few. And in previous centuries, it was also a fixture of military campaigns everywhere. French military leader Napoleon Bonaparte once said "an army travels on its stomach. Soup makes the soldier." The peace treaty in Switzerland in 1529 between the Catholics and Protestants concluded with soldiers from both sides sharing a "milk soup" from the same pot. For centuries, daily pots have simmered over fires and stoves around the globe.

It was out of this ubiquity that the bouillon cube was born.

A Brief History of Concentrating Soups

Humans have been attempting to make soup into convenience food for millenia, and portable soups—essentially concentrated stocks—were a feature of nomadic cultures for thousands of years. In the 14th century, the Magyar warriors of Hungary boiled salted beef until it fell apart, cut it into pieces, dried it in the sun, ground it into a powder, and carried it around in small bags—something of a forerunner to the packets of Lipton’s Cup-o-Soup. Early British cookbooks included recipes for homemade dehydrated soups, like the "veal glew" in The Receipt Book of Mrs. Ann Blencowe from 1694, and a beef-leg version in Hannah Glasse’s 1747 The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy. In the late 18th century, Benjamin Thompson, also known as Count Rumford—a British loyalist who fled New England—invented a forerunner to the bouillon cube: solidified stock of bones and meat trimmings to feed the Duke of Bavaria’s army. He later established meal centers for the poor where he served his mass-produced dehydrated stocks, adding grain for a hearty meal, essentially creating "soup kitchens."

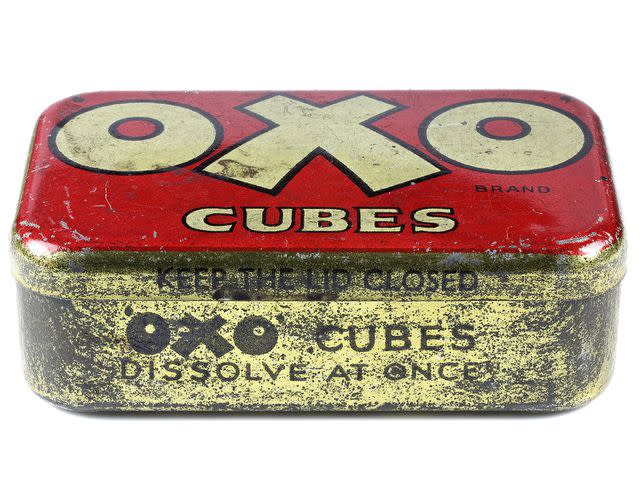

The invention of the bouillon cube as we know it took place at the turn of the century in Europe, with three companies—Maggi, OXO, and Knorr—puzzling through how to create inexpensive portable soups. In 1847, the German chemist Justus von Liebig developed an industrial method for concentrating beef solids into an extract, but the cost of European meat made it too expensive for commercial production. After locating cheaper meat sources in Uruguay, his company, Liebig's Extract of Meat Company, came out with a liquid bouillon under the brand name Oxo in 1899. Meanwhile, in Germany, food manufacturer Carl Heinrich Theodor Knorr, who was experimenting with dehydrated foods, launched dried soups in 1873.

In the early 1880s, Swiss food manufacturer and miller Julius Maggi, whose company also produced packaged soups, used a process known as acid hydrolysis to extract meaty flavors from wheat. Adding hydrochloric acid to plant matter at a warm temperature breaks it down and separates free amino acids, resulting in an ingredient called hydrolyzed vegetable protein, or HVP. One of the amino acids in HVP is threonine, which imparts the flavor of meat at a lower cost than meat itself. Maggiwurtz, Maggi’s readymade soups and sauces, were the first to use it. He then used HVP to invent bouillonwürfel, the bouillon cube, which also included a meat extract, likely beef, and introduced it commercially to Europe in 1908.

That very same year, in Japan, chemist Ikeda Kikunae, inspired by his wife’s miso soup, derived monosodium glutamate (MSG) from kombu—a building block of the Japanese stock, dashi— and also used acid hydrolysis to extract amino acid from soy beans around the same time. Kikunae coined the term "umami," a portmanteau of the Japanese words "umai" (delicious) and "mi" (taste), for the flavor derived from the amino acids, including glutamate and threonine, in meat, mushrooms, and fermented foods.

In 1910, the British company OXO introduced its bouillon cube, as did Knorr (which today uses a combination of autolyzed yeast extract, which frees amino acids using its own enzymes, and MSG) in the French market that same year, following with a liquid bouillon extract in 1912 in Switzerland—all of those bouillon products chock full of umami.

Shutterstock

It wasn’t long before these European bouillon cubes started proliferating in countries around the globe, penetrating indigenous foodways in the process. During World War I, OXO provided 100 million bouillon cubes to the British armed forces, and launched one of the world’s first global marketing campaigns, with the foil-wrapped cubes spreading throughout colonized countries in the early 20th century. Early advertisements, boasting that they would "improve meat dishes" and "made good dishes better," also claimed that "digestion is assisted" and "development of a healthy physique and an active mind is promoted." Today, Knorr sells 600 bouillon cubes per second globally, with 10 of those in the US. During the 2020 coronavirus pandemic, bouillon cube sales jumped by 70 percent, according to Knorr, between February and March.

Bouillon Cubes Across the Globe

Perhaps the bouillon cube has had no greater success than in the Central and West African market, where Maggi, which is also a top seller in Brazil, India, Germany, and the Middle East, has become synonymous with classic dishes from the region, like jollof rice and poulet braisé. The company has tailored its product to cater to local preferences, with different flavors (a C?te d’Ivoire cube incorporates cassava) and textures (in some countries, the consistency is made so that cooks can crumble it over dishes while cooking), and today sells more than 100 million cubes in Central and West Africa daily.

"As far as I can remember, there was always a jar full of red and gold wrapped cubes in most of the West African kitchens that I’ve visited," says Dakar, Senegal native Pierre Thiam, who owns the Brooklyn-based West African food company Yolélé. "They are so popular that I’ve even seen people crumbling bouillon cubes directly on their plates for added flavor." He’s dubbed the prevalence of Maggi "cubism," with the bouillon cube mixed into the national Senegalese dish, thieboudiene, a fragrant rice and vegetable dish with fish stuffed with a piquant parsley mixture called "rof," and yassa, charcoal-grilled chicken or fish smothered in a caramelized onion and lime sauce. Maggi has aggressively advertised in Senegal, using popular wrestling champions—wrestling is more popular than soccer there—on billboards, alongside the country’s national dishes.

It’s a similar story in Nigeria, where Maggi markets its products to busy working women like it did in post-industrial Europe, and has made its way into restaurants, home kitchens, and cooking blogs. "The Maggi is more widely available than iru," says Simileoluwa Adebajo of Eko Kitchen in San Francisco, referring to the fermented locust bean paste used by the Yoruba and Edo people. "The capacity of a company like Nestlé [which owns Maggi] or Unilever [which owns Knorr] to distribute cross-country, you can go to the most remote part of Nigeria and still find someone selling Maggi cubes. If a company is making enough money in a country no matter how underdeveloped it is, they will get their product to every single corner of that country."

Likewise, in Mexico, Rico told me that in his grandparents’ small villages in San Luis Potosi, where most people have their own gardens and chickens, cows, and pigs, there are no grocery stores, but there are little convenience stores, and they always keep the cubes in stock. Even when his grandmother made chicken stock from scratch, "she would always want more flavor from it so she would add a couple cubes of that to her chicken stock just to give it a deeper flavor in the mole," says Rico.

While Rico nixtamalizes corn for the handmade tortillas at Nixta Tacqueria, he’ll also "bust up" a Knorr cube at home when cooking for himself and his girlfriend. "MSG works wonders and it does what it’s supposed to. That whole Chinese Restaurant Syndrome is bullshit," he says, referring to the myth that the flavor enhancer, which is the second ingredient in a Knorr bouillon cube, causes adverse health effects. "It’s racism in a way. [MSG] just makes things more delicious."

West African–made bouillon cubes, like Doli, Adja, and Bongou, are also growing in popularity in their home countries. But in previous generations, a wide variety of fermented pastes provided the umami flavor to West African cooking, including iru (also called dawadawa or nététou or sumbala), yett (fermented conch), toufa (fermented sea snail), guedj (dried fermented fish), ogiri (fermented bean paste), among many others. Unlike the odorless bouillon cubes, these indigenous products have a strong, pungent smell, and preparing them can be a "process on its own," including soaking and cleaning, according to Adebajo. "Sadly, the convenience of cubes has come to the detriment of these wonderfully funky ingredients which are now threatened of disappearing," says Thiam.

Adebajo believes there’s a generational difference attributed to multinational corporations socially conditioning consumers into thinking "that they need the cube," with marketing campaigns like the YouTube show Yelo Pepe, which follows the lives of five women for recipes and "drama." "A lot of older women in Nigeria don’t like Maggi cubes in their food," she says. "The older generation that prefers that natural indigenous flavor, and the younger generation that just wants the meals to be ready in the next 45 minutes." Her grandmother was upset upon learning that Adebajo was using bouillon cubes in ayamase, a local stew from her village of Kenar, until Adebajo tracked down some people to bring her iru and ogiri from Nigeria to replicate her grandmother’s method. Still, she concedes that "the maggi cubes are great for beginner cooks" who are just dipping into Nigerian recipes, which often employ time-consuming techniques.

In addition to displacing traditional umami products, there’s also the question of salt content. "Unfortunately, the general thinking for many is that the more bouillon cubes there are in the pot, the more flavorful the dish," says Thiam. "However, bouillon cubes generally have a high sodium content. There needs to be more education on how bouillon cubes abuses can be detrimental to our health." In 2017, Senegal did just that by limiting the salt content of all cubes to 55 percent. And that may be the key with the concentrated umami seasonings: restraint.

Maggi started importing to China in the 1930s, and Knorr has also established itself in other parts of Asia, as well as its diaspora; Lee Kum Kee is also known for making a bouillon powder. "For me, I thought of it as an immigrant thing," says chef Thomas Pisha-Duffly of Gado-Gado in Portland, Oregon. "Everyone was using bouillon in the '50s. When we moved here, that’s what they had. I don’t think of bouillon cube as an Asian ingredient. I guess it’s colonialism." His grandmother, like Rico’s, incorporates it in traditional Indonesian dishes: "any chicken dish, and her perkedel, her fritters, all have bouillon in it." While Indonesia is now the top market for Knorr bouillon cubes, Pisha-Duffly’s grandmother only discovered it once she immigrated to the US. When he recounted making stock with beef bones, his grandmother would react in astonishment, "she says, ‘Thomas, that’s crazy, who has time to do that? We used to do that when I was a kid when we were poor but now you can just buy this thing that tastes better.’"

Many Indonesian dishes just don’t taste the same without it, says Pisha-Duffly, echoing a common refrain around the world where bouillon cubes have been adapted in classic dishes. But Pisha-Duffly, who enthusiastically maintains that even a perfectly made dashi is improved with a touch of MSG, doesn’t see a problem with that. "If I’m going to make my grandmother’s babi kecup, which is pork braised in sweet soy, we’ll take the time to make a really nice pork stock," he says. "But then we’ll augment it with bouillon."

July 2020

Read the original article on Serious Eats.