Lenny Kravitz's Guide to Immortality

ONE THING LENNY KRAVITZ has been trying to tell us all along is that another world is possible—a better world, a world guided by love and not by fear, where people choose unity and peace over division and self-destruction. In a world more like that one, the past few months might have gone very differently for almost everyone, including Lenny Kravitz. He might have spent spring and summer as he’d originally intended, playing a run of concerts in Australia and New Zealand and then everywhere from Lithuania to Lisbon, in support of his 2018 album, Raise Vibration, a record that, like most Lenny Kravitz albums, seems to summon gyrating supermodels out of thin air every time you play it, an album that opens—as his recent shows usually have—with Lenny singing the Prince-goes-to-“Kashmir” anthem “We Can Get It All Together,” asking to be delivered from his loneliness and selfishness and brokenness so that he can join hands with the rest of humankind.

Instead, in early March, as the spread of COVID-19 picked up speed, Kravitz left his house in Paris and caught a flight to the Bahamas, thinking he’d hang out at his place on the island of Eleuthera for a few days until things went back to normal. His tour luggage had already been shipped to Australia; he landed in the islands with a few pairs of jeans in a weekend bag. “And I’ve been living out of this weekend bag,” Kravitz says, “for almost five and a half months.”

In Eleuthera, in the one-room house he finally got around to putting up after sleeping on the beach in an Airstream for years, he is alone, except for Leroy and Jojo, the potcake dogs—Caribbean mutts, both adopted off the street, boon companions even though they don’t talk (although at this point, Kravitz says, “I’ve been here so long, I’m starting to hear words”). In the photos on Lenny’s Facebook feed, it looks like a pretty idyllic exile experience, all things considered. Here is Lenny, shirtless and barefoot, changing a tire on an old Volkswagen Bug. Here is Lenny playing guitar by a calm blue ocean. Here is Lenny carrying home his banana crop in two overflowing baskets. Here is Lenny, no more immune than any of us to the cumulative psychic weight of the past few months, just sitting in a corner feeling it all (photo caption: “Feeling it all”). The photos depict a man living sparsely, thoughtfully but not unhappily alone.

Which is not to say Kravitz is averse to owning things. He’s still got the place in Paris’s upscale 16th Arrondissement, a four-story 1920s townhouse with a speakeasy in the basement, Warhols and Basquiats on the walls, and room for a collection of mementos that once belonged to myriad heroes—Prince’s guitar, John Lennon’s shirt, a closetful of James Brown’s dancing shoes, and a pair of Muhammad Ali’s boots complete with a tiny dried fleck of Ali’s actual blood.

Contemplate the yin-yang of Paris Lenny and Eleuthera Lenny long enough and a unified theory of Kravitz presents itself: He’s the last mass-cultural rock star standing, because no one else is willing to unselfconsciously embody all the contradictory archetypes of the profession, from sensualist/maximalist decadence to antimaterialist beach-bummery. He lives up, at all times, to our dream of what Lenny Kravitz might be doing at any given moment, because in an age of live streamers, he remains a performer, which is something different. That’s true even now, on this island—someone is framing and taking these man-alone photos he’s posting on Facebook, after all, and it’s probably not the dogs.

Today, a pixelated Kravitz bobs into view on a Zoom call, wandering that house in search of a more favorable wireless signal. His image comes into focus, then freezes, becoming an accidental selfie of the rock star as castaway—jean shirt buttoned south of his sternum, a chunk of green mineral around his neck on a piece of rope, hexagonal silver shades reflecting jungle and a strip of white sky. He turned 56 in May, but only the dusting of gray in his stubble gives that away; add a soul patch and he could pass for Lenny at 25. The most effective way to stay perennially cool is to never visibly age, if you can pull it off.

He finds a signal and a seat and begins to talk about the island, where confirmed cases of COVID-19 are low but everyone is being very careful. You can leave your property to buy food, but only on certain days. And yet this life doesn’t feel like deprivation. It never does. “When I’m here, I pretty much live that way anyway,” he says. “It’s a beautiful thing to really realize what you don’t need. If I have to stay here another five months, five years, I’m good.”

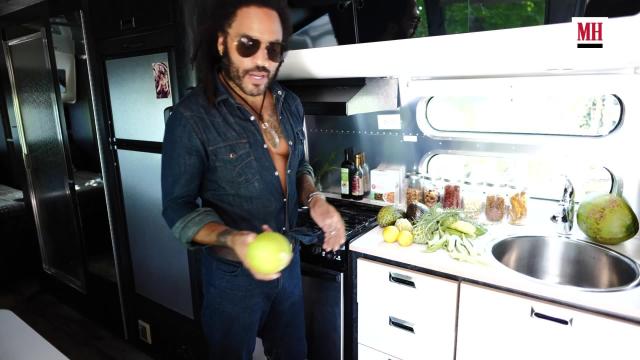

MOST DAYS out here he’ll wake up and check his crops—it’s the dry season, but he’s got some things growing on his land. Cucumbers, okra, watermelons, passion fruit, sugar apples, soursops, pomegranates, coconuts, mangoes. Herbs, too—lemon grass, five-finger grass, moringa, cerasee. Bush medicine, his grandparents used to call it: “You’re feeling this. Go pick this. Make a tea.”

His roots in this part of the world go deep. His grandfather Albert Roker was born on Inagua, down by Cuba and Haiti at the southernmost point of the Bahama island chain. “He lived up until his 90s, but even up into his 80s, he was ripped,” Kravitz says, shedding light on his enviable genetic legacy. “Black island man. Like iron. He had a workout that he would do in the backyard that consisted of a tree and a leather belt and, like, a broom handle. All resistance.”

Since the late ’90s, Kravitz has worked with Miami-based trainer Dodd Romero, whom he credits with helping him maintain a slinky silhouette and the stamina to play three-hour concerts well into his 50s. The routine is targeted—fasted cardio in the morning, cardio before bed so he’s burning all night, weights throughout the day. These days, they work together via FaceTime, Kravitz says, “and we always have a goal in front of us. My best shape is not behind me. It’s in front of me right now. We keep moving that bar as we get older.” But in Eleuthera he’s had to improvise a little, Albert Roker style. He’s found trails on his property, runs through the bush on grass and dirt. “That’s been my cardio,” he says, “and then I moved some hand weights over next to a coconut tree that basically comes out of the ground sideways, so that’s now my bench, and I lift weights on this coconut tree. I’m doing a complete jungle workout.”

What he hasn’t been doing is recording. Gregory Town Sound, the concrete--bunker-like studio where he recorded his past three albums, survived without a scratch when Hurricane Dorian pounded the Bahamas in 2019 but has been out of commission since last year due to flooding. “A piece of PVC pipe about this big,” Kravitz says, holding up his thumb and finger to indicate something half the size of a doughnut, “under the bathroom sink, burst one night and took out my entire studio.” Not being able to make records this year has been tough, because Kravitz has a few things on his mind.

Back in 2011, Kravitz released a buoyant, funk-infused album called Black and White America. It’s a pure product of Obama-era optimism; the cover photo is a preteen Lenny with a peace sign painted on his forehead, and the title track contrasts the world in which his Black mother and white, Jewish father met and married—“And when they walked down the street, they were in danger”—with the new reality seemingly heralded by the election of America’s first Black president:

There is no division, don’t you understand

The future looks as though it has come around

And maybe we have finally found our common ground

“Isn’t it amazing,” Kravitz says, laughing, in 2020, “that we thought that’s what was coming?”

ANOTHER WORLD is possible, but it begins with pointing out what’s wrong right here. Although he has a not undeserved reputation for patchouli-dipped utopianism, Kravitz has been writing about systemic racism since his very first album, 1989’s Let Love Rule—“Mr. Cab Driver” is about how a dread can’t get a ride uptown. He wrote “Bank Robber Man,” a borderline--punk rager from 2001’s Lenny, after being arrested and cuffed on his way to the gym by Miami police who’d mistaken him for a suspect. And when Minneapolis police officers killed George Floyd in May, touching off a summer of insurgency in cities across America, Kravitz reached back to Let Love Rule again, posting “Does Anybody Out There Even Care”—a Beatlesque lament that mentions lynching as well as “riots in the streets”—on his Facebook page.

“I’ve been talking about this stuff,” Kravitz says. “I would have thought we’d be in such a better place than we are now. That we would have evolved. Not that it would have been anything close to perfect.” Raise Vibration, so far the only Kravitz album released during the Trump era, felt like a hopeful soundtrack to resistance—a syncopated protest march that might end at a rooftop party. Given everything that’s happened since, I ask Kravitz if he has any plans to address this comparably grim American moment. “That’s what I can feel is coming, obviously,” he says. “There’s things to say. There’s a lot of things to say.”

In the meantime, he’s been practicing—playing his own songs, sometimes, but also mastering tiny hidden details on records he thought he knew by heart. Zeppelin, Hendrix, Marley, Pink Floyd, Chuck Berry—the classic rock on which he’s built his church. Kravitz is getting ready to publish a book, too, also titled Let Love Rule, which among other things is a memoir of those influences and how they changed him. In junior high he gets stoned for the first time and his friend throws in a cassette of Zeppelin’s “Black Dog,” a moment Kravitz compares to the light-speed jump from Star Wars. “It opened up a whole new world for me,” he says, “in sound and attitude and music and songwriting and guitar.”

In the book, Kravitz is born in New York in 1964 to the Obie-winning theater actress Roxie Roker and Sy Kravitz, an assignment editor at NBC News; moves from Manhattan to Los Angeles when Norman Lear casts Roker on The Jeffersons as Helen Willis, George Jefferson’s neighbor and part of the first interracial couple on prime-time TV; acclimates by learning to skateboard and get high; and settles into the well-to-do Black neighborhood of Baldwin Hills.

He sings with the California Boys’ Choir at the Hollywood Bowl; finds God when a friend invites him to pray at choir camp; finds Prince, whose mix of R&B chops and guitar firepower opens another portal; and trades his Afro for a Jheri curl. He starts his first band; decides “Lenny Kravitz” sounds “more like an accountant than a rock musician”; and temporarily rechristens himself “Romeo Blue.” He turns down big-break-ish record deals with companies wanting something different from Romeo Blue than Kravitz wants from himself, forgoing these opportunities even while living in a Ford Pinto he rents for $4.99 per day.

He passes, for example, on a chance to record his friend Kennedy Gordy’s song “Somebody’s Watching Me,” which becomes an R&B hit when Gordy records it himself under the name Rockwell. “I turned things down,” Kravitz says, “because my spirit wouldn’t allow me to do it. And I wouldn’t be here now, talking to you, if I had taken those opportunities.”

Kravitz describes the book as “an enormous therapy session.” The strongest force in it, apart from Kravitz’s own will, is his father, Sy, a disciplinarian ex–Green Beret and Korean War veteran who Kravitz says “enabled me to become who I needed to become, through our conflicts.” Eventually, Kravitz discovers that his father has been cheating on his mother. As Sy is walking out the door with suitcases in hand, Roker tells him to say something to his son, and after a long pause, Sy looks at Lenny and says, “You’ll do it, too.”

“Those four words, man,” Kravitz says, “affected me more than I knew.” He acknowledges that they have shaped how he’s acted in relationships and his approach to fidelity. “There were times in my life where that was very difficult, and I didn’t understand why,” he says. “I love my father, and we made peace before he died, but I held on to some things that had affected me in our relationship, and through writing the book . . . I was able to strip away some of the judgment that I had held on to and got to just see him as a human being.”

In the mid-’80s, after a chance meeting in a backstage elevator at a New Edition concert, Kravitz and The Cosby Show’s Lisa Bonet became friends, then close friends. She was a rising star and would soon be leading the cast of a college-set Cosby spin-off, A Different World. Kravitz was a wannabe rock star who sometimes lived in a midsize hatchback. They married in 1987, at the Chapel of Love in Las Vegas on Bonet’s 20th birthday, and spent time in the Bahamas, where Kravitz fell in love with Eleuthera. Then Bonet found out she was pregnant with their daughter, Zo?. Bonet was married; Denise Huxtable was not. Decades before the revelations that led to his sexual--assault convictions, Bill Cosby still had an image to maintain. He refused to write this real-life plot twist into A Different World’s second season and pulled Bonet from the cast.

Bonet cowrote two songs on Let Love Rule; Kravitz says her creative influence helped him realize that the world needed Lenny Kravitz, not Romeo Blue. “The voice I was looking for, the name, the image, was already there,” he says. “It was the first time I’d opened up like that, and had known love like that, and freedom. And watching her do what she did, how she maneuvered, in her artistic life—it was that last thing I needed, on this road. This sound, this message, this movement that I was looking for—I heard it in my head. That’s the way I still work to this day. I wait until I hear it in my head. That takes my ego out of it. It may not be what you thought you were looking for, but it’s what you get.”

Largely self-produced and almost entirely self-performed, Let Love Rule crossbreeds Curtis Mayfield and John Lennon and Jimi Hendrix in what we now recognize as classic Kravitz fashion, but the songs were anything but a hot commodity at first. After countless A&R types told him his music was either too Black or too white to sell, he signed with Virgin Records, then had to talk them out of releasing a slicked-up version of the album remixed to compete on the radio with the likes of Bon Jovi. By the early ’90s, thanks to everything from the bubblegum oldies on the Reservoir Dogs soundtrack to Beck playing folk music in corduroy flares, the ’70s would become a totemic hipster reference point, but in the late ’80s, Kravitz’s retro affinities made him a man without context.

“As if compelled to self-destruct, Kravitz courts artistic disaster by continually evoking his betters,” Rolling Stone sniffed, before acknowledging his guitar tone, his ear for sonic detail, and his way with a groove. The record peaked at number 61 on the Billboard charts but eventually caught fire in Europe, where Kravitz is still huge. He’s been triumphantly out of step ever since; he walks down to that concrete studio by the water, plugs in, and makes rock records that exist outside of time. “He’s not an early bird,” says Kravitz’s Eleuthera neighbor Craig Ross, who’s toured with him since 1991 and played on every album since 1993’s Are You Gonna Go My Way. “And when that happens, I go, ‘Oh, he must have dreamt a song last night and he wants to get it out.’ Otherwise he’d call me in the afternoon.”

The book ends with Kravitz married and on his way to stardom at the age of 25, leaving off before 1991’s Mama Said—Kravitz’s breakthrough album, the source of “It Ain’t Over ’til It’s Over,” an aching megahit addressed to Bonet. They divorced in 1993, when Zo? was four; she grew up primarily with Bonet in L. A., then moved to Miami at 11 to live with her rock-star father. Kravitz says his daughter has grown up to be “the most real person I know,” noting that her path to independent success as an actress and producer can’t have been easy. “Just having two parents who were known in the world. The comparisons. She didn’t let any of that hinder her in any way.”

These days, Kravitz is close to Bonet and seemingly even closer to her new husband, Aquaman star Jason Momoa. “People can’t believe how tight Jason and I are, or how tight I still am with Zo?’s mom, how we all relate,” Kravitz says with a shrug. “We just do it because that’s what you do. You let love rule, right? I mean, obviously, after a breakup, it’s work—it takes some work and time, healing and reflection, et cetera. But as far as Jason and I? Literally the moment we met, we were like, ‘Oh, yeah. I love this dude.’ ”

There is nothing in the book about any of this, nor about the time Kravitz split his leather pants onstage in Stockholm, inadvertently revealing his penis to the crowd and subsequently to the entire Internet. “I don’t even think about it,” Kravitz says about his big reveal. “Y’know, John Lennon was [naked] on the cover of that Two Virginsrecord. If he could do that, then it’s whatever.” The book is essentially about a young man following his heart, refusing to bend for commercial exigency, and falling in real love for the first time ever. I ask if the Kravitz we’d meet in a hypothetical second volume would be a more complicated character, perhaps even an antihero. Lenny laughs. “Oh, it gets real messy,” he says. “It gets really interesting. Things turn upside down.”

This story appears in the November 2020 issue of Men's Health.

You Might Also Like