Listen to Survivors, It's the Only Way This Gets Any Better

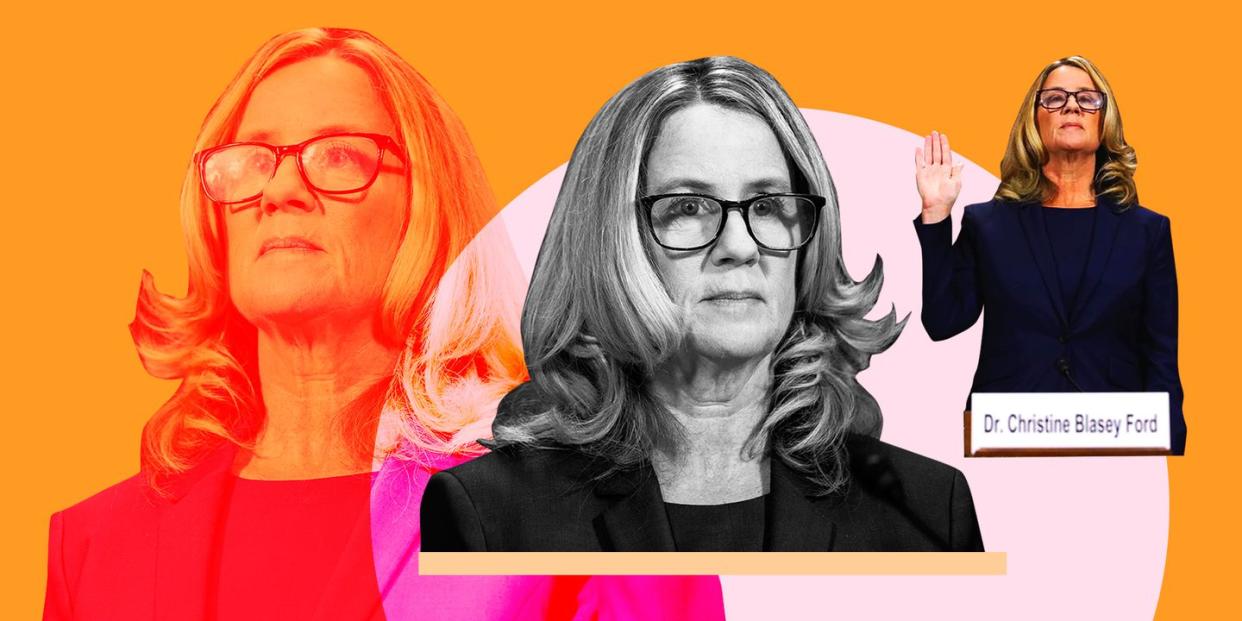

Over the course of four hours on Thursday, the country watched as Christine Blasey Ford politely and calmly answered questions about one of the most painful moments of her life: an alleged assault by Supreme Court nominee Brett Kavanaugh that she says took place 36 years ago, when she was just 15.

Ford publicly identified herself earlier this month as the woman behind previously anonymous allegations that a young Kavanaugh got "stumbling drunk" at a high school party, corralled her into a bedroom, pinned her down, attempted to remove her clothes, and held his hand over her mouth when she tried to scream.

Since then, the past two weeks-and Thursday in particular, as Ford voluntarily allowed prosecutor Rachel Mitchell to question every detail of her 36-year-old memory-have served as a collective dredging of repressed assault stories. Survivors of assault are sharing their stories online, in broadcast calls to C-SPAN, at rallies, with reporters, in texts, with anyone who will listen. Who will listen?

We are drowning in each other's stories, as political consultant Jess McIntosh pointed out, many of which have been percolating beneath the thick haze of trauma for decades, and are only resurfacing now. It's both powerful and overwhelming, and leaves a lot of people feeling understandably helpless, because there's nothing you can really say to undo or fix someone else's pain. But what so many survivors want as they recount stories is something very simple: to be heard.

The constant consumption of other people's pain-pain that's often very similar to your own-is traumatic in its own right. In a 2017 story for Cosmopolitan.com, Larisa Pham, a trauma response worker, referred to the phenomenon as "vicarious trauma," or "a heightened state of tension and preoccupation directly as a result of taking on other people’s emotional pain." In the onslaught of new stories of sexual harassment and assault, survivors were finding it difficult to simply be online.

That same thing is happening now, as Ford and Kavanaugh dominate the news cycle. As Pham noted, it's good that allegations are being heard, and rising to a space where it seems like they might actually bear serious weight. It's good that Ford was allowed to testify. But as survivors see elements of their own pain in Ford's story, and as their own trauma comes flooding back in unexpected ways, they may also feel the same invalidation Ford faces as Senate Republicans and others seem to suggest her story doesn't matter.

In the recesses during the hearing, C-SPAN aired phone calls from survivors who recalled assaults remembered by watching the Ford hearing. In many of their stories was the sort of built-in defense so many survivors offer, knowing the likelihood they won't be believed. "I was the victim of abuse when I was 13 and I came out close to 30 years old," said one called. "It does not make you less credible because you come out 17 years later. It can take a lot of time to process these things that happen to you when you are underage."

The common thread among the C-SPAN callers, and the innumerable survivors who've shared their stories the past few weeks, is a desire to be heard. And as someone consuming these stories, as you're able, the kindest thing-the most important thing-you can do now is listen. RAINN advises that "often listening is the best way to support a survivor." In an essay about the deluge of women speaking up about experiences with sexual misconduct in the era of #MeToo, Jia Tolentino writes that "being heard is one kind of power" for survivors. And implied in the call to #BelieveSurvivors is the necessary first step of listening to them.

From the very beginning, Ford has said she was reluctant to come forward because she didn't want to put herself through this process for nothing. "Why suffer through the annihilation if it’s not going to matter?" she told the Washington Post when she first attached her name to the allegations.

While it remains to be seen if Ford's testimony affect's Kavanaugh's confirmation, for survivors, it does matter. It opened up a space for them to speak. Now what we have to do is listen-listen to how many stories there are, listen to the ways survivors defend their stories as if they're on trial, listen because it's often the only thing a survivor telling you their story wants you to do. There's no fixing something that's already happened. But there is forward motion, and there's momentum in the swell of survivor stories, and the power of watching Ford on the Senate floor.

Follow Hannah on Twitter.

('You Might Also Like',)