Midwife's arrest shines light on rural America's home-birth 'crisis'

When Elizabeth Catlin gave birth to her first child in a hospital over three decades ago, she was pushed into what she felt was an unnecessary C-section, and it sparked in her a new passion: home birth. She went on to have all but four of her children — 14 in total — at home, and in between having her own babies began working as an assistant to a local home-birth midwife. As Catlin’s daughters became adults, one told her, “Mom, we’re going to want you to catch our babies,” and it prompted her to take her passion a step further — by working toward national certification and formalizing her knowledge through a four-year Idaho-based midwifery college.

Catlin became what’s called a certified professional midwife (CPM) through the program, and eventually began serving not only her daughters, but many other local women, as a trained birth attendant.

“I had intended to work with my daughters,” says Catlin, 53, speaking with Yahoo Lifestyle in early February at her peaceful home in Penn Yan, N.Y., a scenic sweep of upstate farmland hugging the northern tip of Keuka Lake. “And then the Mennonites started calling me.”

There are approximately 700 Mennonite families in and around Yates County — and Catlin (who is not Mennonite) has caught most of their babies. By her own estimate, she has attended more than 500 births.

So it was a crushing blow not only to herself and her family but also to the community at large when Catlin was taken away in handcuffs and put in jail, for practicing midwifery without a license.

She was arrested at her home, twice, in late 2018 — first in November, for practicing without a license (a felony), after she was reported to authorities by F.F. Thompson Hospital in Canandaigua, N.Y., where she had transferred a Mennonite woman having a difficult labor, and where the baby was born and, shortly thereafter, died.

Catlin was then arrested again in December, just a few nights before Christmas, on related felony charges, for allegedly continuing to practice. Her 8-year-old daughter watched her get handcuffed and then led away into the dark. Catlin spent the night in jail and was then bailed out by many in the Mennonite community, who quickly raised about $8,000.

“Everybody flocked towards her,” Rosalyn Sauder, a mom of two who was one of Catlin’s first clients, tells Yahoo Lifestyle in a recent interview at her family’s farmhouse, a snowstorm swirling outside. “She has such a good personality and is compassionate, and word of mouth spread. She never advertised.” Her sister Brenda Zimmerman, also a mom of two, adds, “She wasn’t just our midwife, she was our great friend also. It wasn’t like she was just delivering our babies. She was like a mom to a lot of us.”

Both are Mennonites, adherents to the Old Order culture who, similar to the Amish, reject military service and political office, and avoid most modern conveniences — including the internet, TV, radio and automobiles (with some but not all orders relying on horse-drawn buggies) and unnecessary medical interventions, especially when it comes to birth. By all accounts, the women of the community deeply love and trust Catlin. And despite the quiet stoicism that’s the norm for women in their culture, they have been speaking up loudly in her defense.

Although Catlin is experienced and professionally certified, she is not licensed to practice midwifery in New York — a particularly complicated state within the country’s complex pastiche of midwifery laws. New York offers a clear path to licensure for only two types of midwives: certified nurse midwives (CNMs), who are licensed in all states and must earn a master’s degree, maintain an active registered nursing license and graduate from a CNM education program; and certified midwives (CMs), a relatively new class of provider, who must also earn a master’s degree, follow a specific non-nurse educational preparation and then take the CNM-equivalency exam. There are approximately 10,000 CNMs in the country, and while many do attend home births, the majority practice in hospitals, often alongside obstetricians; there are fewer than 100 CMs in the U.S., mostly in New York (which created the certification), though they are also recognized in Maine and Rhode Island.

Certified professional midwives (CPMs), meanwhile, like Catlin — of which there are nearly 3,000 in the U.S., almost all of whom attend births at their clients’ homes — become nationally accredited either through an apprenticeship or educational program, or a combination of the two.

While CPMs are licensed to practice in 31 states, New York is not one of them.

There was once a mechanism for granting an exception, based on comparable education and the passing of an exam, but that changed in 2011. Now midwives like Catlin, despite their knowledge and experience, cannot take the exam because they don’t have a master’s degree. And some birth activists believe that the way the law has been implemented is not in keeping with its original intent.

“Liz would’ve had a license but for the failure of the midwifery board and the education department to implement the statute the way it was written in 1992,” contends Susan Jenkins, legal counsel for the Big Push for Midwives, a national lobbying effort for CPM licensure. Also, she notes, “There is a section of the New York Education law that allows the Board of Regents to waive the exam requirement with a showing of good cause.”

In January, Vicki Hedley, president of the Midwives Alliance of North America (MANA), wrote an open letter calling for other midwifery organizations to support Catlin and more inclusive regulations in New York. “There is no legal justification for limiting the practice of midwifery in New York to Certified-Nurse Midwives and Certified Midwives,” it read in part.

But Susan Stone, the president of the American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM), the professional organization for nurse-midwives, says that getting involved in an active case “would not be right.” Still, she tells Yahoo Lifestyle, “Nobody — nobody — wants to see midwives arrested for practicing, especially a certified midwife,” and emphasizes, “ACNM does support licensure for CPMs.”

The situation is multilayered, politicized and confusing. And Catlin is just the latest to find herself caught in the middle of it all.

Now many alternative-birth advocates and practitioners, in interviews with Yahoo Lifestyle, say they are looking at Catlin’s arrest as a symbol of an American home-birth culture in crisis, maintaining that overregulation, misconceptions about midwifery, and biases from the medical establishment continue to restrict women’s access to having the safely attended births of their choice — only making home birth less safe, they say, by driving some midwives underground. (The New York State Education Department’s Office of the Professions midwifery unit, did not respond to Yahoo Lifestyle’s requests for comment.)

Also adding an element of danger is the lack of integration between home-birth midwives and hospitals — something Kate Finn, an Ithaca, N.Y., licensed midwife and board member of the New York State Association of Licensed Midwives, targeted when she helped craft evidence-based guidelines for safe, compassionate transfers from midwife to hospital, free of threat to the midwife. Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester signed the agreement and was to have the smaller F.F. Thompson Hospital (where the laboring woman was transferred) follow suit; Finn is unsure whether that ever happened. “It’s an ethical issue,” she says. “The same quality of care should be offered to every woman coming through the door, regardless of the provider with her, and without endangering the provider.”

Beyond stating that Catlin was not a member of any hospital medical staff and “did not practice here in any way, shape or form,” neither hospital would comment on the case for Yahoo Lifestyle, citing the federal law restricting the release of medical information.

Catlin’s arrest has galvanized the Mennonite community she served like nothing before — inspiring scores of the women (and many men), unaccustomed to protesting or making a scene, to rally in her defense at court dates and through a flood of letters sent to local papers, as well as by fundraising for her bail and other legal costs (including through a GoFundMe page). When investigators suggested that Catlin had been tricking Mennonite women for years, the women angrily denied the idea in local reports. “She was always upfront with us,” Sauder tells Yahoo Lifestyle. “She was not fooling or exploiting us.”

The case has also fired up a national network of alternative-birth advocates, who believe fiercely in the right of women’s access to home births attended by midwives — who approach birth not from a medical perspective, as physicians do, but as a normal physiologic event, following the woman-led Midwifery Model of Care, and transferring high-risk pregnancies to obstetricians.

“Criminalizing women for helping other women have babies tells us all that women still are not free to make our own health care decisions, even about something so extremely personal,” says Cristen Pascucci, founder of the birth-rights organization Birth Monopoly and director of Mother May I, a forthcoming documentary on institutional abuse in maternity care.

“The punitive treatment of women helping other women related to their health — and the narrowing of women’s options as a result — goes back a very long time,” she adds, referring to the marginalization and systematic eradication of traditional midwifery from the U.S. health care system starting in the early 1900s, largely the result of anti-midwife campaigns by the medical establishment, as well-documented in histories including Mainstreaming Midwives: The Politics of Change by Robbie Davis-Floyd and Christine Barbara Johnson.

“In 2019,” notes Pascucci, “women’s health is still not in our own hands.”

For now, as Catlin awaits the next step in her case — a decision on whether she’ll be indicted by a grand jury or see her case handled by a judge, or dismissed — she is barred from practicing.

“I feel antsy and anxious and out of my element right now,” she says, sitting at home with her 8-year-old.

The expectant mothers in the area, already underserved when it comes to home-birth midwives or even ob-gyn services, are in a state of shock, with some planning to use the services of less-qualified, uncertified birth attendants who practice discreetly in the area, and others completely unsure of what they’ll do, remaining hopeful that Catlin will return. At least two women have reportedly had unattended home births since her arrest. And according to several Mennonite women, a group of four CNMs from the Rochester area (one of whom Yahoo Lifestyle reached out to several times, with no response) have sent around letters offering their services at a discount — although women say that the offered price, which would be paid out-of-pocket, is at least double what they paid Catlin, and thus unfeasible.

“This illuminates a situation in New York state, especially in rural communities, where there is no OB care available in that county. There are growing numbers of women everywhere choosing out-of-hospital births, and there is no option, but a growing demand,” says Linda Schutt, a retired licensed midwife and former chair of the New York Board of Midwifery who, following Catlin’s arrest, was able to briefly take over her heavy prenatal client load — around 40 Mennonite women. “The [unlicensed certified] midwives are trained and experienced to attend happy, normal births at home, and yet they have no mechanism to practice.”

Ivan Martin, a Mennonite elder and de facto community spokesperson (and father to 13, most of whom were born at home) sees the fight for women to birth their babies as they choose not as a Mennonite or religious-freedom struggle, but as a civil rights issue.

“It’s odd to me that, culturally speaking, we have people that argue for ‘death with dignity’ and the rights of abortion — mother’s rights, a woman’s right, ‘hands off my body’ and that whole thing,” says Martin, speaking to Yahoo Lifestyle in his kitchen, a piano accordion at his feet (he repairs the instruments) and his wife, Anna, working at her sewing machine in the next room.

“So, it’s not so much that I agree with those particular points — but if that’s a concept that has any validity, should it not apply here, when it has to do with the beginning of life?” says Martin, who added, “It’s something that I would think all civilized people should see as a precious thing.”

Catlin’s case: ‘The illegal part is calling yourself a midwife’

Home birth, to put it in context, is not common in the U.S., accounting for not quite 1 percent of all births. But while the percentage is small, the actual number is substantial, nearly 39,000 and rising, the result of more women wanting to avoid medical interventions (sometimes used through coercion or even force) such as induced labor, epidurals, cesarean sections and episiotomies, or simply wanting to birth on their terms, for whatever reason, whether because of a deeply held belief or a want of convenience.

As Catlin’s early client Sauder explained on behalf of her Mennonite community, “This is one of God’s special miracles that your body is designed to do naturally.” Occasionally, when complications arise, she says, is when you’d go to the hospital.

Although the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the country’s leading ob-gyn professional organization, “believes that hospitals and accredited birth centers are the safest settings for birth,” noting higher at-home risks of perinatal death (3.9 out of 1,000, according to a recent New England Journal of Medicine study), neonatal seizures and neurologic dysfunction, it also notes in its committee opinion on planned home births that “each woman has the right to make a medically informed decision about delivery.”

Of the many studies out there on home vs. hospital births, a 2014 landmark analysis of 17,000 home births, the largest ever, showed that among low-risk women, planned home births resulted in healthy outcomes, including excellent birth weights, high rates of breastfeeding and, following hospital transfer, just a 5.2 percent C-section rate — just a fraction of the national rate of C-sections, which stands at 32 percent.

But the demand for home births outweighs the available midwives in upstate New York (as in many other parts of rural America); the one CNM who had served the community for years died just this month after a long illness. Anyone else certified (or otherwise) in the immediate area is unlicensed, and among the licensed CNMs operating in New York, all but four serve the New York City and nearby Hudson County area.

And, notes Elma Risler, a Mennonite woman whose three children were born at home with Catlin’s aid, even if many of the Yates County women would consider heading to the hospital in Canandaigua, “The hospital is not equipped to handle 200 more births a year.” She adds that the bigger hospital, in Rochester, “is up to two and a half hours away for some, and not feasible,” but that home birth, in any event, “is a personal preference, and the way it was always done.”

Indeed, some unlicensed and formerly unlicensed CPMs in New York, speaking anonymously, tell Yahoo Lifestyle they feel they’d been given tacit approval by authorities because they’d been openly serving rural communities for years. And it’s not unusual for CPMs to practice without a state license, National Association of Certified Professional Midwives president Mary Lawlor tells Yahoo Lifestyle, as the profession itself “grew out of a grassroots movement to reclaim normal birth,” and so many feel that pull of activism, and are compelled to assist where they’re needed. “Because even in states that have no licensing, that doesn’t mean there aren’t people having babies at home who need the service.”

And the midwives who are getting licensed are simply not moving to rural areas, whether because they are hospital-trained, need higher salaries in order to pay off education debts.

Katherine Hemple, campaign manager with the Big Push for Midwives, tells Yahoo Lifestyle, “Until this case happened, there was a feeling of recognition, in general, that CPMs were OK to practice; there wasn’t motivation to change the law.”

Catlin’s case, though, is providing fresh motivation.

“I received a complaint from F.F. Thompson Hospital, Canandaigua, NY, executive staff, in mid-October 2018,” investigator Mark Eifert, who arrested Catlin, tells Yahoo Lifestyle via email. He is leading the investigation, with the input of a representative of the New York State Education Department Office of Professional Discipline. Eifert says he was told that Catlin, “acting as a midwife, had brought a pregnant woman to the hospital’s Labor and Delivery department, after prolonged labor. The baby was born septic and died hours later, after being transferred to Strong Memorial Hospital, in Rochester NY.”

Thompson is not being investigated for the death, Eifert says. “Through my investigation,” he says, “it is apparent that the mother and baby were brought to Labor and Delivery, both already suffering from serious medical problems, as a result of prolonged labor.”

Now Catlin finds herself facing possible prison time for four felony charges — one for practicing midwifery without a license, and three related to her allegedly bringing a blood sample to a lab: falsifying business records, criminal possession of a forged instrument in the second degree, and identity theft.

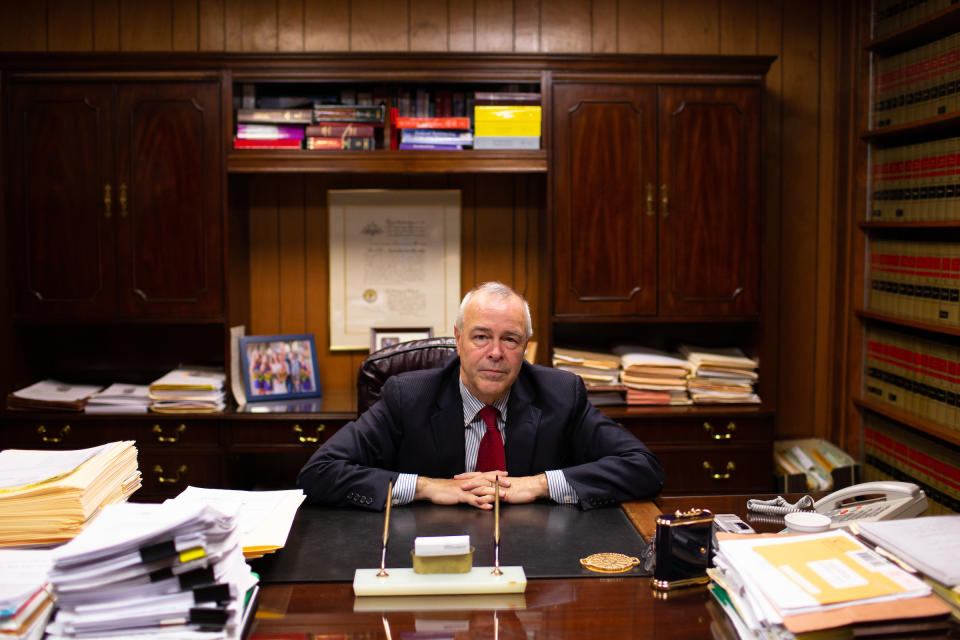

“To assist somebody else as a favor, she dropped off the blood samples. It’s as simple as that,” Catlin’s attorney, David Morabito of East Rochester, tells Yahoo Lifestyle about the three charges related to the lab work. He believes the number of felonies issued was heavy-handed.

“They really overkilled everything,” he says, adding that he’s “very comfortable” defending Catlin on all charges. The “simple defense in a nutshell,” Morabito adds, is that she didn’t “intend” to violate the laws, and that she believed her certification “was appropriate” for her to practice as a birth attendant.

As home birth is legal in New York state, and the birthing mother is entitled to invite anyone she’d like to attend the birth, it seems as if much of the case comes down to semantics.

“The illegal part is calling yourself a midwife,” explains Melissa Carman, a home-birth advocate lobbying for the licensure of CPMs in New York as the president of the nonprofit NY-CPM. “A rule change is the best solution. We are rewriting the rules and intend to meet with the Board of Midwifery.” Regarding the situation in upstate New York, she adds, “We have a huge, huge crisis going on here. People are scared.” Not only moms-to-be, she says, but also the midwives who want to serve them.

As Hemple explains, “CPMs are the specialists in out-of-hospital maternity care. There’s a distinct skill set involved in out-of-hospital settings, sometimes when there is no electricity, no running water. And recognizing that has been a trend in other states.” Further, she says, New York is out of step with much of the rest of the country by using prosecution, rather than looking to change the statute.

“Fundamentally,” Hemple says, “it’s an ignorance of what a CPM does, how she’s trained and why families are choosing this option, which can be for religious, cultural, financial — a range of reasons, including reactions to having experienced substandard hospital care.”

Catlin, though, is far from the first midwife to be arrested in the U.S., with recent incidents of prosecuted midwives occurring in Indiana (most recently within the Amish community there), Missouri, Alabama, North Carolina and Baltimore.

“The problem is that when there is no regulation,” explains Lawlor, “the only recourse for complaints, whether valid or invalid, is the criminal system. So, in theory, if someone has a bias against home birth and they want to come down on somebody who transferred [a laboring woman to the hospital], they have the criminal route available. If there’s licensing, they can’t do that.”

Still, the mere idea of arresting a midwife is a hard one for many to swallow.

“It becomes visceral, because it’s so personal when you are arresting someone who is basically risking her life and her livelihood for the people in the community who she’s serving,” Hedley explains. “And so especially for us as midwives, who have historically been marginalized, it just makes us take a deep breath and realize how vulnerable we are to the system that we have to be a part of — a system that doesn’t even know what we do.”

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

Pregnant with breast cancer: ‘I couldn’t wrap my head around it’

Illegal midwives and border babies: The determined fight for home birth in Alabama

Follow us on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter for nonstop inspiration delivered fresh to your feed, every day.