A thrilling, frustrating George Benjamin premiere at the Proms, plus the best of August's classical concerts

Proms, Mahler Chamber Orchestra/Benjamin, Royal Albert Hall ★★★☆☆

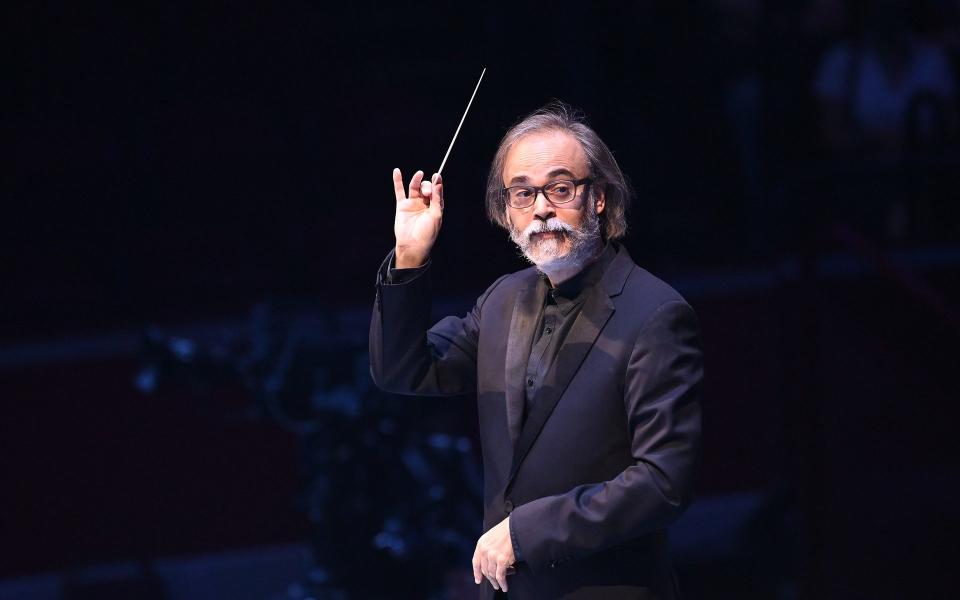

On Monday night, the Proms hosted its sole overseas orchestra of the season, the Mahler Chamber Orchestra. Why this particular exception from the very understandable decision not to invite any foreign orchestras at the tail-end of a pandemic? Partly its small size, which makes it a more manageable risk. But the touring orchestra (which is also the core of the Lucerne Festival Orchestra) was also the perfect match for George Benjamin, the painstakingly perfectionist composer and conductor whom the Proms wanted to salute in his 60th-birthday year, and who says he “adores” working with the MCO.

Benjamin led the orchestra in a programme of glittering and dusky aural magic, with two brand-new pieces of his own alongside Ravel’s much-loved piano concerto, and to begin with an eight-minute potpourri of orchestral mood-pictures by the late Oliver Knussen, Benjamin’s friend of 40 years. Entitled The Way to Castle Yonder, it conjured scenes from Knussen’s second operatic collaboration with famed children’s author Maurice Sendak, in tones of sly Ravel-flavoured nostalgia and mock-sinister magic, all caught to perfection by the orchestra.

There was more aural seduction in Benjamin’s new Three Consorts, which are arrangements of three of Henry Purcell’s fantasias for stringed instruments. You might say that was inappropriate, given that in their original form these fantasias are deliberately monochrome, to focus our ears on Purcell’s austere and technically ingenious interweaving of melodic lines. But there’s mystery too in the music’s spicy harmonic clashes, and poetic melancholy. Benjamin’s subtle additions of muted horn and layerings of orchestral colour gently heightened all this, without losing the music’s essential muted gravity – a remarkable feat of artistic empathy as well as skill.

In the concert’s second half, the level descended somewhat, with wonderful moments interspersed with puzzlement. Ravel’s piano concert was etched with careful precision by Benjamin and the orchestra, almost as if they wanted to eliminate all trace of Gershwin-like pizzazz. Soloist Pierre-Laurent Aimard was similarly unsmiling, and strangely effortful and hard-toned in the long, arching melody of the slow movement.

Then came the evening’s main event, Benjamin’s new Concerto for Orchestra. The title suggests an exuberant showpiece for every player, and Benjamin tells us he hoped to summon up the “energy, humour and spirit” of his old friend Knussen, in whose memory the piece was written. What we actually heard was too dark to be humorous and too nervously changeable to be exuberant.

Benjamin is known as a maker of aural magic and harmonic sumptuousness but, as this piece reminded us, what really obsesses him is creating a compelling narrative that is full of surprise and yet by the end feels inevitable, like fate. The difficulty is that when caught up in this lava-flow, the melodies and harmonies have no chance to take shape. One’s left grasping at half-perceived shapes as they speed by. It’s frustrating as much as thrilling, but the intensity of thought and feeling in those knotted gestures was moving in itself, and worth more than any number of those facile, one-dimensional premieres we’re so often faced with on these occasions. IH

Hear this Prom for 30 days on the BBC Sounds app. Proms tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Prom, The Carnival of the Animals, Royal Albert Hall ★★★☆☆

On paper, this family Prom was a tantalising family affair. The Kanneh-Masons are Britain’s first musical family, thrust into the spotlight three years ago when the then 19-year-old cellist Sheku almost stole the show from Harry and Meghan at their own wedding. The family are now known for having produced not just one ridiculously talented musician but seven, and each one, alongside seven further musicians, was on stage for this centenary performance of Saint-Sa?ns’s evergreen zoological fantasia, having recorded it with brightly coloured vigour alongside Michael Morpurgo for Decca last year. All the greater pity then that, through no fault of their own, the Kanneh-Masons struggled to dominate their own event.

Family Proms are always a little bit chaotic, if charmingly so. But you can hardly blame young legs in the audience for becoming prematurely restless when they’ve been subjected first to the 20-minute opening Revel – a four-part world premiere by British composer Daniel Kidane describing a day in the life of a young Mancunian (narrated with strenuous larkiness by the actor EM Williams) as they attend a carnival.

You waited for the music to generate precisely the promised primal excitement and ecstasy of carnival; instead, you got one piece conveying the jostle of a commute; another evoking the rain. Meanwhile, Lemn Sissay popped up from a sofa to read out self penned poems about the weather. What a mishmash, failing both to dramatise its own subject matter and make any meaningful sense to children. My eight year old spent most of it kicking the chair in front of her.

At least Saint-Sa?ns’s suite – 14 short movements, each devoted to a different animal – is pretty indestructible. Morpurgo was on hand to deliver his poems, which have the same vivid gestural quality as the pieces they accompany. My daughter enjoyed trying to guess which animal was being evoked, with individual details sparkling: piano chords bubbled with eerie beauty on Aquarium, xylophones scuttled madly on the irresistible Fossils, Sheku delivered a sublime solo swan. Young children, including mine, danced along in their seats.

Yet one wishes Saint-Sa?ns and the Kanneh Masons had been allowed simply to get on with the job of animating the animals. There is so much pictorial detail and tonal variation, so many irrepressible dynamics, the individual works scarcely need any accompaniment. Instead, there was an ill-conceived attempt to dress up the whole thing as a performance. Not necessarily a problem in principle, but if you want to go down that route, you need a dramaturg of sorts to pull it all together.

Instead, what we got felt frustratingly diffuse. The increasingly wearisome Williams appeared first wearing a lion’s costume, then used a helmet to depict the tortoise and ping pong balls for chicken eggs, but after that appeared to abandon animal role-playing altogether, presumably leaving those children who had come dressed as animals wondering why they’d bothered. An audience call and response for the cuckoo seemed to go on and on for ever.

Several awkward breaks, prompting unnecessary audience applause between pieces, added to a general sense of disconnect. And it was a crying shame no one thought it a good idea to introduce the individual members of the Kanneh-Masons to an audience full of children, given that the youngest, the cellist Mariatu, is just 11.

“Hmm,” said my daughter after it had finished. “I didn’t really enjoy that very much.” We went home and found the Kanneh-Mason recording on Spotify, and immediately felt much better. CA

Hear this Prom for 30 days on the BBC Sounds app. Proms tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Proms, BBC SSO/Volkov, Royal Albert Hall ★★★★☆

One of the most important commissions at this year’s Proms, George Lewis’s new work Minds in Flux will probably prove the most imposing. It’s not only a substantial 30-minute score but a piece that deliberately takes on the vast spaces of the Royal Albert Hall: mixing orchestral forces with digital electronics, it actually harnesses all the surfaces in the auditorium rather than (as so often in his acoustic) fighting against them.

Turning 70 next year, Lewis counts among America’s senior composers, and has long been a pioneer of experimental music. He has also always been politically engaged in his writings about the “creolisation” of classical music: he speaks from experience, then, when he describes Minds in Flux as a “sonic meditation on what processes of decolonisation might sound like”.

But though this brilliantly performed premiere, given by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra under Ilan Volkov with sound realisation by Damon Holzborn and Sound Intermedia, certainly lived up to the “flux” of the title, Lewis’s actual programme would have been difficult to discern without that signpost. It’s hard not to think of Penderecki’s music for his famous Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima – abstract before the composer added the emotive title. Lewis may be imagining the future, but his work is in some ways a journey back to a past era of musical modernism.

Lewis also quotes the great Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe’s “No Longer at Ease”, yet for all the evocation of anxiety the soundscapes are frequently awe-inspiring. Opening from a cosmic rumble, answered by lonely shrieks, the score takes off in all directions, and with the orchestral principals mic'd up their sound is thrown around the hall. Textures are often busy – and the playing virtuosic – even when the basic pulse feels slow, and the music becomes more energised before disappearing into quiet convulsions. A champion of the new and challenging, Volkov conducted with authority.

Pairing new music with an all-Beethoven second half, Volkov made the case for Beethoven as always sounding modern. Even though the concert aria “Ah! perfido” looks back in a way, drawing its recitative from the 18th-century poet and librettist Pietro Metastasio, there was nothing old-fashioned about its raging at a faithless lover – or about this performance, with soprano Lucy Crowe finding heartfelt depth and signing with glowing, incisive attack.

The accompaniment was lean and alert, a mood carried over into the Second Symphony, in which Beethoven wrangled in the most upbeat way with his growing awareness of encroaching deafness. Volkov drove his responsive players towards a blazing and affirmative close. JA

Hear this Prom for 30 days on the BBC Sounds app. Proms tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Edinburgh International Festival, Ariadne Auf Naxos, Edinburgh Academy Junior School ★★★★☆

In many ways, the Edinburgh International Festival has been one big experiment this year: with hangar-like open-air venues (dubbed “polytunnels”) for chamber and orchestral music; with al fresco opera (Scottish Opera’s rather lacklustre Falstaff) reconfigured to work indoors; and, as the festival nears its end, with proper full-scale, full-length opera (okay, a modest one) in the open air.

And, although director Luisa Muller could hardly offer a full staging of Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos within the EIF’s biggest polytunnel, in the grounds of Edinburgh Academy Junior School, what she presented was lithe, snappy and highly effective, sung off book and in costume in front of the Royal Scottish National Orchestra – which gave a wonderfully stylish, richly glistening account of Strauss’s intricate score under supple conducting from Lothar Koenigs, standing in for an indisposed Andrew Davis.

That was in the opera’s first half, at least. Thomas Quasthoff – in town with his jazz quartet, and also giving a couple of vocal masterclasses at the weekend – was luxury casting in the speaking role of the Major-Domo, nicely dry and officious in delivering his master’s diktat that the two entertainments booked for his high-class soirée – an opera and a slapstick comedy – should happen simultaneously. Edinburgh’s own Catriona Morison was a revelation as the wronged Composer, capturing the lofty musical ideals that s/he’d now have to compromise in a voice of buoyant beauty, effortlessly floated and full of persuasively visionary wonder.

Though her vocal prowess was never in doubt, Brenda Rae was surprisingly subdued as the flirtatious Zerbinetta, but Dorothea R?schmann commanded the stage in her brief entries in the opera’s title role, capturing the singer’s fragile ego brilliantly. All hurried entries and sudden exits, Muller’s light-touch staging found just the right blend of farce and fluidity within the limited means at her disposal.

So far, so good. So far, so captivating and revelatory, in fact. But where there’s usually an interval, Covid rules dictated that the performers plough on immediately with the opera-plus-sideshow, and things went somewhat awry – not only because of the break-less evening of more than two hours, and the constant trickle of punters making a dash for the portaloos. No, most bewildering was the absence of opportunity to reset psychologically, and to move mentally from the story’s behind-the-scenes bickering into the auditorium itself. The result was that, after the frenetic activity of the prologue, the opera within an opera felt sluggish by comparison, offering Muller little by the way of the quick-change scenes she’d engineered so deftly earlier on.

Nonetheless, attention sharpened noticeably with the arrival of David Butt Philip’s powerful Bacchus and the opera’s rapt closing duet, during which R?schmann seemed to transform physically in body and posture, inspired by love and hope. Despite its tonal inconsistency, it was a brave, ambitious performance. And alongside its admittedly risky experimentalism, as the sun cast a dying glow over a pleasantly balmy Edinburgh opening night, and a gentle breeze wafted through the polytunnel, it felt like a unique, almost certainly one-year-only experience, and one therefore to be cherished. DK

The EIF continues until Aug 29. Tickets: 0131 473 2000; eif.co.uk

Proms, The Eight Seasons of Buenos Aires, ASMF/Bell, Royal Albert Hall ★★★☆☆

It’s just as well that Astor Piazzolla was born in 1921, not 1920. Fans of the tango composer, not to mention anniversary-loving programmers, would have missed their chance to celebrate him at the Proms, but at least this year’s programme – albeit a scaled-back one – has managed to mark his centenary. Pinning Piazzolla’s Four Seasons of Buenos Aires to the original and enduringly popular Four Seasons of Vivaldi created enough demand for the Proms to add this extra, afternoon performance as the curtain-up to the initially scheduled evening show.

Jumping on the bandwagon, if not the bandoneón, were the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, who with their music director Joshua Bell as soloist nearly succeeded in turning the Albert Hall into a tango bar. This was, for those keeping a tally of such things, Bell’s 21st appearance at the Proms, and though the Indiana-born violinist may often seem more of a cool cucumber than a torrid tanguero, Piazzolla sounded reasonably authentic in South Kensington; perhaps more authentic indeed than Vivaldi, since the clean playing of the ASMF lacked Italianate spirit, giving us Venice as viewed from a cruise liner.

In fact, Piazzolla was a proponent of “nuevo tango”, applying his style to a mix of forms – not least in María de Buenos Aires, the intimate opera that has done well in these pandemic (and centenary) times. Though born in the Argentinian resort of Mar Del Plata, he had Italian blood on both sides of his family, which perhaps comes through in his homage to Vivaldi. Not that his Cuatro Estaciones Porte?as, or Four Seasons of Buenos Aires, were originally planned to be played alongside the Quattro Staggione: they were written for his bandoneón ensemble and arranged only later (by the Russian composer Leonid Desyatnikov) for chamber orchestra to make a clearer connection.

To avoid the seasonal dislocation of a foggy Venetian day bumping up against a sultry Buenos Aires night, the hemispheres were mostly brought into line, with only Spring split to frame the sequence – Vivaldi’s to start, Piazzolla’s to close. The contrast between countryside and city was still felt, and nature did burst through in the opening Vivaldi concerto. Yet most of the highlights came in the Piazzolla pieces: his Summer was played with attack, if not dangerous edge, and his Winter evoked wistful desolation. If nothing else, eight contrasting seasons in one short concert made this a programme for modern, climate-change times. JA

Hear this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Edinburgh International Festival: Joyce DiDonato and Il Pomo D’Oro ★★★★★

It is a sign of our times that on Monday evening, the great American mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato thanked the Edinburgh International Festival effusively for inviting her to sing in what is, in effect, a gazebo in a field.

To be fair, the vast, temporary auditorium the Festival has erected in the handsome district of Inverleith, in the north of the city, is impressive enough to host the grandest of weather-threatened royal garden parties. However, no one could claim that the makeshift venue, which sits on the considerable playing fields of Edinburgh Academy Junior School, has the acoustics of a great opera house. Not that this mattered to DiDonato, who spoke passionately about the social importance of the return of live music at a time when calamitous news headlines threaten to overwhelm “the light” that the art form brings us.

DiDonato, who is Irish-American and from Kansas (the Italian surname comes from her first marriage), was joined by the extraordinary Italian period instrument ensemble Il Pomo D’Oro, singing a rich and diverse selection of her favourite arias from the Baroque operas. The concert opened with the ensemble offering a virtuosic and dynamic rendering of Sinfonia grave à cinque voci by Salamone Rossi. Then, DiDonato came on stage, resplendent in a startling pink gown, to the unmistakable strains of Monteverdi’s ‘Illustratevi o cieli’ from Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria.

Does the music of any composer, apart from JS Bach, come closer to expressing the voice of God than that of Monteverdi? To hear DiDonato perform from the operas of the great innovator of the Italian Baroque was to be transported to the outer edges of human experience. Il Pomo D’Oro, for their part, delivered the music with an energy and zest that spoke to the predominant youth of the ensemble, and to a skill that belied it.

When DiDonato sang of spiritual self-realisation, as she did in Johann Adolph Hasse’s Antonio e Cleopatra, she was gloriously exultant. When, by contrast, Monteverdi transported her to bitter sadness, as in L’incoronazione di Poppea (“Farewell, Rome... farewell homeland friends, farewell! Though innocent, I must leave you”) her anguish was devastating.

One often hears singers talk of their voice as their “instrument”. A truly great singer, such as DiDonato, proves that, no matter how splendidly tuned that instrument is, it grips the soul only when it is coupled with a deep and intelligent emotion.

This was made abundantly apparent in her performance of ‘Dopo notte’ from Handel’s Ariodante. By the time, in lines that express her socio-artistic creed, she had sung the Italian words that translated as, “For in the midst of a violent storm my boat was almost sunk, but it grasps the shore as it returns to port”, the grateful audience was cheering her to the temporary rafters. MB

The EIF continues until Aug 29. Tickets: eif.co.uk

Proms, LSO/Rattle, Royal Albert Hall, London SW7 ★★★★☆

Having decimated much of the musical world over the last year and a half, the pandemic is now leaving its mark on those concerts that are happily going ahead. Few of this year’s Proms show much of the old programming flair, though the compromises that have been made are perfectly understandable. All the more reason, then, to welcome such a carefully crafted programme as this all-Stravinsky concert by the London Symphony Orchestra under Simon Rattle, an event that truly belonged in the 2021 season, marking as it did the 50th anniversary of the composer’s death.

Although Stravinsky played fast and loose – sometimes very loose – when using “symphony” as a title, the focus here on three of his Symphonies traced a fascinating arc across a sizeable chunk of his output, all in the space of a compact concert given without an interval. True, we didn’t get the early Symphony in E flat, nor the blazing masterpiece that is his Symphony of Psalms, yet there was real rigour in the sequence heard here.

Most of Stravinsky’s symphonic essays date from his neo-Classical period, but his earlier Russian idiom informs the Symphonies of Wind Instruments, with its echoes of Petrushka and Rite of Spring. There’s a pungency about this music that was superbly caught in Rattle’s conducting, always alert to the sense of ritual.

Performing the original version, premiered in London a century ago, the players – woodwind and brass – summoned up powerful depths and strident shrieks, as if creating the musical equivalent of a Constructivist painting. And the lugubrious chant heard at the end was a reminder of the original meaning of “symphonies” as a “sounding together”.

The Symphony in C, unheard at the Proms in 30 years, made a welcome and attractive centrepiece. Rattle and his orchestra caught the gentle agitation of the opening, and the smooth polish of the strings (with the masked string players sharing desks) gathered edge and intensity as the first movement unfolded.

For all its implied neo-Classical clarity, the piece is built on constantly shifting ground and Rattle controlled things firmly while allowing the music to create a free-flowing impression. Similarly, the finale’s transformation from throbbing energy into an eventual clearing of the air was magically handled, creating a sense of arrival in more ways than one, since the work was begun in Europe but completed only in 1940 after Stravinsky’s arrival in America.

By contrast, the Symphony in Three Movements was Stravinsky’s first American score, and it packs a big, brassy punch. Yet the prominent piano and harp parts lend the work subtle sonorities, too, which create the impression of fluidity even if in the best performances – this one included – they are tightly controlled. Conductor and orchestra were at one as they drove the restless, relentless finale towards an exciting conclusion. JA

Hear this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Edinburgh International Festival: The Soldier's Tale ★★★★☆

The Soldier’s Tale seems to have found a comfortable home in many ensembles’ concert programmes – whether live or online – over the past 18 months. You can see why. With opera thin on the ground, this work about a violinist trading his instrument with the devil inreturn for untold riches, offers a pint-sized music theatre experience using just seven instrumentalists and a couple of actors. Social distancing is a breeze. But the work’s origins in trauma and turmoil give it a particular resonance in our own pandemic times, too: stranded in Switzerland following the Russian Revolution, Stravinsky conceived it with writer CF Ramuz in the wake of the devastation of the First World War, and it’s a world apart from the lavish decadence of his earlier music. A planned 1918 tour had to be cancelled because of the ‘Spanish’ flu pandemic.

The Edinburgh International Festival’s performances formed the final panel in a triptych of concerts featuring violinist Nicola Benedetti. Truth be told, though, and despite a brilliant scarlet dress setting her apart from the other instrumentalists, Benedetti was here very much first among equals, joined by an ad hoc ensemble drawn from Scottish and London orchestras.

It felt, however, as though the septet had been performing together for years: their playing was perky and propulsive, their ensemble so sharp you might cut yourself on it, and their evident delight in cueing each other and swapping ideas back and forth only added to the sense of theatre. BBC SO principal Philip Cobb’s cornet, in particular, was a joy to experience, and you could hear his years in brass bands from his gloriously rich, vibrato-laden tone. Benedetti came into her own, too, in the three dances with which the Soldier wakes a slumbering princess, each beautifully characterised: a raw, gutsy tango, fluttering waltz and brittle, clipped ragtime.

The more conventional theatre, however, took place out front, led by assured narration from Sir Thomas Allen, erstwhile star of opera stages, now a respected director, and here also responsible for the show’s modest though effective staging: a table, a chair, and a bit of movement from Anthony Flaum as the homecoming Soldier and a redoubtable Siobhan Redmond as the Devil who tricks him. Flaum balanced bravado and vulnerability nicely as the naive recruit, though in truth he doesn’t get much to go on, even in the still witty 1950s English translation by Michael Flanders and Kitty Black. Redmond, on the other hand, began in gleeful mischievousness but revealed ever darker levels of menace as the show progressed, a mere flick of her finger leaving nobody in doubt as to who was in charge.

There was, however, a problem with amplification. No doubt because of Benedetti’s pulling power, the Festival had plumped for its biggest outdoor venue – used elsewhere for its orchestral concerts – for the performances. On a particularly dreich, drizzly Edinburgh afternoon, however, it wasn’t easy to discern the dialogue from row F, let alone from 20 rows further back. Thank goodness for the overhead supertitles.

But this is a far from conventional year, of course, and audiences are happy to make allowances. Sound issues aside, this was a gloriously vibrant, thoroughly committed yet nicely knowing performance, and Allen’s simple staging provided just the level of theatricality that this unconventional work demands. You could scarcely hope for a more spirited, energetic musical backdrop, though even the instrumentalists’ playing grew more sober as the tale headed towards its concluding moral. Don’t try to get back what you once had, intoned Allen’s suddenly serious narrator, and be happy with what you have today. There was a lesson there in 1918, and there is a lesson for us today too. DK

The Edinburgh Festival continues until 29 August; eif.co.uk

Mozart’s Requiem, Proms, review ★★★☆☆

Grab the audience by the scruff is the first rule of show-biz, and the Proms certainly obeyed it last night. The first sounds we heard were a howling gale and the crash of thunder, summoned by the percussionists of the Britten Sinfonia on thunder-sheets and wind-machines. Was a musical storm in the offing? No, it was just to give a bit of extra drama to a couple of rustic dances lifted from the 1739 tragedy Dardanus by Jean-Philippe Rameau.

This was the first item in a sequence of pieces by the great French Baroque composer performed by the Britten Sinfonia under David Bates. Heightening the latent drama of music is always Bates’s aim and he uses the most extraordinary range of bodily gestures to achieve it, at one point standing arms pinned to one side and shaking his whole body, to give an effect of energy constrained before being released.

In the first part where the music was all on the small-scale of “character” pieces, Bates’s approach worked well. Rameau’s dances had a thrilling rhythmic bite and tangy orchestral colour, and the performance of the Second Symphony by Joseph Bologne Chevalier de Saint-Georges, one of the first black composers in history (the Chevalier’s mother was a slave in the French colony of Guadeloupe) also leaped into vivid life.

It was fascinating to hear Bologne’s piece side-by-side with Rameau’s music: one could catch lingering echoes of the Baroque courtliness of the latter’s worked echoed in the former’s, mingled with the new forward-moving dramatic Mozartian style of his own age.

Alongside the dances were two tragic arias from Rameau’s operas, sung with affecting but somewhat small-voiced tenderness by soprano Samantha Clarke and tenor Nick Pritchard. One’s ear was drawn more to the lovely bassoon accompanying parts, eloquently played by Sarah Burnett and Shelly Organ.

After the interval the charming magic and make-believe of Rameau was set aside for something on a different level of seriousness, Mozart’s Requiem. The orchestra was joined for this by the National Youth Choir, and two more soloists, the contralto Claudia Huckle, whose creamy voice was a pleasure, and bass William Thomas, who was much the most characterful of the soloists. His splendid opening flourish in the Tuba Mirum was the performance’s highlight.

It’s true the Requiem has its most moments of drama as in the Dies Irae, and Bates made these maximally vivid, with sudden surges and retreats in dynamics. The problem was that he applied this small-scale approach across the whole piece, with the result that the music lost much of its breadth.

The magnificent rising melody of the Lachrimosa should feel like a continuity, despite the breaks in the line. Here it felt like a series of small explosions. The singers of the National Youth Choir sang their hearts out, but I couldn’t help feeling the piece was inappropriate for their light bright sound. Youthful lightness has its charm, but sometimes the gravity of adult voices is indispensable. IH

Hear this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Proms, Nubya Garcia, Royal Albert Hall, London SW7 ★★★★★

There's no surer way to test a new friendship than to mention you’re into jazz. Confess a penchant for late-period Charles Mingus at a party, and you’ll either have made a bosom-buddy for life. Or – more likely – you’ll watch as your acquiance darts panicked glances at the exit and mutters, “I’m just going to get another drink.”

For those constitutionally averse to tooting and parping, I’d suggest one cure: Nubya Garcia. Jazz can feel cold, remote, affectless. Not hers. Making her Proms debut on Wednesday night, the 30-year-old British saxophonist played music that was joyous, soulful and actually made you want to get up and dance.

Garcia is at the forefront of a generation of young musicians who are making London the most exciting place in the world for jazz-heads (and agnostics). She exemplifies its alchemy. Whether working with her pioneering all-female collective Nérija, or in residence at Jazz re: freshed, the heartbeat of this movement, her music draws on American traditions, the capital’s home-brewed grime and garage, and her Guyanese-Trinidadian roots. Imagine the smoky smoulder of a New Orleans bar spiked with the frisky energy of a Peckham block party.

She began her set with Source, the title track of her Mercury Prize-shortlisted debut album, released last year. A jittery, questing beginning, slightly swamped by overly assertive drums, led to a series of huge cries from Garcia’s sax. Then came a spectacular piano solo from Joe Armon-Jones: switching between a baby grand and keyboards, he zapped up and down like he was wrestling an electric eel. This, it was clear, was not your granddaddy’s jazz.

The next two tracks – The Message Continues and Pace – eased off the gas. The slow, sunken beauty of The Message Continues was led by a languorous dialogue between the double bass, piano and sax. Pace, meanwhile, began with a gorgeous solo from Daniel Casimir’s double bass. Spot-lit, the massive auditorium utterly still, he moved as though he was playing only to himself. Garcia and trumpeter Sheila Maurice-Grey brought things to a stomping, furious conclusion.

“This song is for anyone who is grieving. I hope you feel less alone after it,” Garcia introduced Together Is a Beautiful Place to Be, a tribute to a friend who had died. Her sax was sombre, gentle, easing its way into the vast spaces left by loss. It reminded me of Alice Coltrane’s exploratory style or Sun Ra’s woozy, far-out rhythms. But after mourning, celebration: Garcia led her band in a swell of pure joy that got the audience dipping and diving. “I never thought I’d see people skanking in the Royal Albert Hall,” beamed my companion.

But dancing was hard to resist on the final song, La cumbia me está llamando, a hip-shaking fiesta of Latin American beats. “I still can’t believe I’m here,'' concluded Garcia, with a grin. "But I’m getting used to it.” And so she should. If this is the future of jazz, then everyone needs to be listening. AD

'Source' is out now. Hear this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Royal Scottish National Orchestra/Edinburgh International Festival ★★★☆☆

I may as well confess it; the Edinburgh Festival’s newly built, Covid-safe, marquee-style stage at the Academy Junior School has lost its charm. Perhaps it’s the peculiar amplified sound, devoid of real resonance but with a disconcerting virtual-reality sharpness, which works well for the bright sounds of winds and percussion but wasn’t at all good for the softer all-strings sound of last night’s concert. Perhaps it’s the way the temperature seems to plummet just as the music gets under way. Perhaps it’s the freshening breeze tugging at the tent’s rigging, making all manner of odd creakings and flappings. This must have been how musical entertainments sounded on an Atlantic clipper.

Concentrating on the music in such circumstances isn’t easy, and one couldn’t be sure that a muddy-sounding texture or halting rhythm wasn’t due to lapse in one’s concentration rather than the music-making. But it’s fair to say the performances from the Royal Scottish National Orchestra didn’t always shine. I haven’t mentioned a third factor that militated against clarity of sound and expressive intent: the peculiar conducting style of star Russian conductor Valerie Gergiev. Those curious fluttering hand gestures seemed more puzzling than ever, and sometimes it sounded as if the players were as bemused as I was.

Still, Gergiev is an interesting musician who rarely gives a dull concert. The programme consisted of three Russian pieces, two of which had the full-blooded expressivity and sharply-etched contrasts which suit his temperament. He certainly found some fresh angles on Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings, particularly in the Waltz which he took at an unusually reflective pace, making the pauses so long that time for a moment seemed to stand still. It gave the music a kind of rapturous nostalgia.

In the second piece, Shostakovich’s sardonic Concerto for Piano, Trumpet and Strings, Scottish pianist Steven Osborne (standing in for Russian virtuoso Daniil Trifonov) and the orchestra’s principal trumpeter Christopher Hart took centre-stage. Hart’s moment to shine was in the second movement, where he moulded the peculiarly bitter-sweet melody with lovely eloquence. Osborne by contrast seized the ear whenever Shostakovich’s strutting, sarcastic vein took over, playing with exactly the heartless brilliance the music needs. At the end he and Hart and the orchestra drove onwards to a truly manic pace, exciting because it was almost out of control, but not quite.

Those two pieces are robust creations, which can tolerate the happenstance of a breezy Scottish evening. Stravinsky’s ballet Apollon Musagète (Apollo Leader of the Muses) is by contrast a quintessentially indoorsy piece, a hyper-sophisticated refraction of the manners and gestures of the French Baroque through a modern sensibility. It needs perfectly quiet surroundings and a performance of delicate grace, with plenty of air and space in the innumerable long-short rhythms. Alas those rhythms felt stodgy here, and in the radiant and moving Apotheosis, where Apollo “wrests his lyre from the Muses and raises his song heavenwards”, Gergiev’s vague flutterings actually caused the performance to come adrift. It wasn’t his or the RSNO’s finest hour.

The Edinburgh Festival continues until 29 August; eif.co.uk

Edinburgh International Festival, Chineke!, Edinburgh Academy Junior School ★★★★☆

When Britain’s first black-majority orchestra Chineke! was founded by famed double-bass player Chi-chi Nwanoku in 2015, it seemed quite cautious. Proving its credentials in the orchestral mainstream and reviving historic black composers such as Samuel Coleridge-Taylor appeared to be its chief aims.

Since then, the orchestra has spread its wings, venturing into contemporary music and commissioning new pieces from black composers, sometimes with a sharp political edge. Tuesday night’s concert at the Edinburgh Festival offered the latest of these new pieces, alongside a 20-year old piece by the sixtysomething Scottish composer and Master of the Queen’s Music, Judith Weir. But there wasn’t a single note of protest or anger to be heard. Instead, the whole seventy-minute concert breached a warm humanity, suffused with humour and wit and generosity, which chimed beautifully with the warm evening sunshine all around the marquee venue in which the concert took place.

First off was the evening’s new piece Blush, a ten-minute orchestral workout from a musician better known as a singer-songwriter who often accompanies herself on the cello, Ayanna Witter-Johnson. She described her piece as “inspired by the excitements and the ups and downs of young love,” but judging from the lithe music there were more ups than downs. Little scraps of bright melody danced over repeating basses and Latin-flavoured percussion, with the occasional harmonic and tempo shift to keep us on our toes. The sheer morning-run-in-the-park lightness of this piece about love came as a shock, but that may just reflect my long immersion in romantic song-cycles, where love isn’t really love unless it’s suffering and unrequited.

In Witter-Johnson’s piece, lightness seemed merely light, though in a charming way. Judith Weir’s Woman.life.song, originally composed for famed African American soprano Jessye Norman, was a different matter. The piece launched off in a similarly weightless vein, in fact the bright, guitar-and-celeste sounds all perched in the treble region with no bass at first seemed like a continuation of Witter-Johnson’s piece. But over time this meditation on the different seasons of a woman’s life from childhood to adolescence to maturity developed real gravity and a power to move.

Much of that power came from the extraordinary poems on which the songs were based, which were sometimes funny (Clarissa Pinkola Estés long poem on a prepubescent girl’s excited anticipation of her breasts raised some laughs) but more often were filled with an immense archetypal gravity, a quality seized on by the evening’s soloist Andrea Baker. She may not have had Norman’s burnished magnificence of sound, but she was more expressively flexible, able to switch instantly from the impatience of young love to humour to a prophetic, gospel-ish eloquence.

Underpinning everything was Weir’s tellingly enigmatic music, revealed in the beautifully poised playing of the orchestra under William Eddins. These elements cohered into something mysterious and direct, intimate and vast, all at once. It felt like a real masterpiece, and Chineke! are to be congratulated for giving Weir’s piece a new lease of life. IH

The EIF continues until Aug 29. Tickets and details: 0131 473 2000; eif.co.uk

Víkingur ólafsson, Proms, review ★★★★☆

The Proms has turned a corner. The first two weeks felt a bit forlorn, with the Royal Albert Hall half empty. Last night it was packed, and once more we could feel that special Proms electricity in the air and hear it in the music-making.

However, the pandemic still cast its baleful shadow over the proceedings. The back row of violinists and cellists were perched oddly in the stalls, to achieve proper social distancing. And the Philharmonia’s new principal conductor, Santtu-Matias Rouvali, couldn’t make what was supposed to be his Proms debut, owing to quarantining issues.

His stand-in, the hugely experienced chief conductor of Zürich’s Tonhalle Orchestra, Paavo J?rvi, was a more than worthy substitute. He can communicate rhythmic energy with a mere flick of the wrist, and we saw much of that flick in the opening piece, Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony. This ought to have been a perfectly formed piece of pert toy-box neo-classicism, and often it was. But if there’s one rule in concert planning it’s that you shouldn’t start with this piece. It sounds light and easy, but is actually really hard. Unless wrists and fingers are warmed up the piece will emerge as it did here, with edges occasionally smudged and the en pointe melody of the 2nd movement sidling in too gingerly to smile as it should.

From that point the concert was an unalloyed joy. After the Prokofiev there loped onto the stage the long-legged, boyishly bespectacled figure of pianist Víkingur ólafsson, to play Bach’s F minor keyboard concerto. Despite the boyish looks he’s actually 37, and before he hit the big time honed his art slowly during years of obscurity in his native Iceland. That was evident in his deeply pondered performance of Bach’s concerto which on the surface seemed almost penny-plain.

He took the first movement at an unusually deliberate pace which allowed him to give the tiny echoes of the orchestra’s phrase a massive weight. He didn’t load the melody of the slow movement with ornaments as some players do, instead playing it with daring, hushed simplicity. One felt the audience leaning forward to savour its fragile, limpid shapeliness, the orchestra tip-toeing alongside him in perfect harmony.

By this time one had the impression that ólafsson’s specialism is spinning a melody as perfectly distinct and glowing as a string of pearls. But in the final movement he summoned a completely different sound for his rapid-fire alternations with the orchestra, massive yet graceful like a dancing giant. The same amazing variety of touch and musical intelligence was evident in his performance of Mozart’s melancholy and severe 24th Piano Concerto. As with all really fine musicians, ólafsson’s numerous expressive touches were anchored in the music’s form.

While his right hand shaped a melody with exquisite sensitivity, his left hand would help us to grasp the harmonic movement, becoming more assertive when an important harmonic destination hove into view. He forswore the now habitual ornamenting of Mozart’s melodies to achieve a telling simplicity, but also invented some brilliantly insightful linking passages, and his cadenza (solo spot) in the first movement was striking in its angry taut concision - was it possibly his own?

I could devote a page to ólafsson’s numerous subtleties, but J?rvi deserves some space too for his brilliant handling of Shostakovich’s apparently humorous but ultimately enigmatic Ninth Symphony. And the orchestral players also deserve praise: clarinetists Mark van de Wiel and Jennifer McLaren for their beautifully nostalgic duet in the second movement, bassoonist Emily Hultmark for the desolate lament of the fourth, and the teamwork that made the uproarious finale such a joy. IH

Hear this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Proms 2021, LPO/Jurowski, Royal Albert Hall ★★★★☆

Just as big-name pop bands can always manage one more farewell tour, so big-league conductors can always give one more farewell concert. Back in June, Vladimir Jurowski conducted what was billed as his swansong as the London Philharmonic’s Principal Conductor, at the Royal Festival Hall. On Thursday night, they were reunited for a Prom.

One could only be grateful for the second chance – especially as we could also enjoy the moment at the end of the concert where Jurowski was awarded the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society. No other conductor offers such a vivid demonstration of the way grace and utility go together, in fact they’re two sides of the same coin. Jurowski’s balletically graceful gestures are also supremely effective in conjuring playing of beautiful rhythmic poise, as this Prom showed.

Another reason to welcome this second swansong was that, unlike the first, it showed off Jurowski’s adventurousness in concert programming, which during his 14 years at the LPO has been second to none (another reason he so deserved that Gold Medal). He launched off with what is perhaps Stravinsky’s least-played ballet score, Jeu de Cartes (A Game of Cards), in which the perfidious joker helps the other cards to win the first two “deals”, but is finally defeated in the third. The ballet flashes by in a dazzling sequence of pert little marches, can-cans, polkas and waltzes, laced with near-quotations (including an outrageous steal from Rossini) and scraps of finely shaped melody.

In previous performances I’ve found its relentless brilliance a bit wearisome; on this occasion it was a joy, because of the fabulous tautness of the playing, the shapeliness of those little scraps from the LPO’s wonderful principal players – and the way they caught the violence of the ending, which for a moment recalled The Rite of Spring.

Frankly, that performance alone would have been worth turning out for, but there was much more. In Walton’s autumnal Cello Concerto, the orchestra found a miraculously different sound, full of nocturnal sultriness and mystery. Cellist Steven Isserlis played the solo part as if to the manner born. He caught with perfect exactness the piece’s strange moon-struck quality, the way Walton’s surging virtuosic leaps trail off in an atmosphere of indefinable yearning coloured with the sounds of a Mediterranean night.

The next piece was at the opposite pole of aloof, abstract pattern-making, made by music’s greatest master of counterpoint, JS Bach. In 1975, a set of fourteen canons by him were discovered, and two years later they were orchestrated for a brightly coloured group of 14 players. In this performance, the dancing melodies, engaged in ingenious “follow-my-leader” games of ever-increasing complication, shone out with lovely, na?ve clarity.

Clarity was also a key note in the performance of the final piece, the Symphony Mathis der Maler by Paul Hindemith. This homage to the painter Matthias Grünewald, which leads to a final affirmation after nightmarish spiritual travails, has always struck me as deeper in its aspirations than in its actual musical substance. On this occasion, the tremendous expressivity of the playing made me think I was wrong, and that it really is a masterpiece. You can’t ask more of a performance than that. IH

Hear this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Edinburgh International Festival Opening Concert, Edinburgh Academy School ★★★★☆

After a silent year, live music is back at the Edinburgh International Festival. That’s something worth celebrating, and the Lord Provost of Edinburgh, the Scottish Culture Secretary Angus Robertson and a full house were there to witness the opening concert, given by the BBC Symphony Orchestra. However, the pandemic still casts a shadow. The festival director Fergus Linehan took the decision to forswear the splendid Usher Hall, the normal venue for concerts, as social distancing couldn’t be guaranteed there. Instead we were in one of three specially constructed International Festival venues, a large rectangular tent open to the winds set in the grounds of Edinburgh Academy School.

Fortunately, the threatening grey weather didn’t turn nasty, and only the occasional disconsolate squawk from a seagull spoiled the calm. Sound quality in such a venue is always a problem, but the array of more than 50 speakers around the hall magnified the sound so subtly that one was only subliminally aware of an extra silvery sheen on the glockenspiel and brass.

That was absolutely right for the music, which was chosen to lift the spirits and bring some Mediterranean sunshine into the traditional Scottish summer. The curtain-raiser was a newly commissioned piece from Anna Clyne, a one-time student at Edinburgh University and now a flourishing composer in New York. Its title, Pivot, made one expect something severely abstract but the piece turned out to be a witty homage to an Edinburgh pub once named the Pivot that is a well known centre for folk music.

With its opening brass fanfare, its tipsy evocations of Scottish dancing and occasional sudden turns to oboe-flavoured melancholy, it had all the ingredients of those jolly overtures that composers such as Malcolm Arnold were composing back in the Fifties. But the astringent sound-world, the startling switch-backs in the form and the intriguing rhythmic “kick” in the dance held that period cliché at bay. It takes real skill to compose something musically engaging that is also right for the occasion, and Clyne proved she has it in spades.

With the next piece, Botticelliana, astringency was swept away in sumptuously warm string trills, swirling harps and tinkling glockenspiels. Respighi’s homage to the great Italian Renaissance painter Botticelli needs playing of rapturous sweetness to come to life, which the BBC Symphony Orchestra under conductor Dalia Stasevska provided in abundance.

Astringency of a delightfully energising, tangy kind came back in the final piece, Stravinsky’s Pulcinella. It was performed in the complete ballet version with three vocal soloists who sing about happy shepherdesses, the agonies of love, and those scheming women who “keep a hundred men on a leash”. As people have noticed ever since the 1920 premiere, it’s impossible to discern a plot in this song-and-dance mélange, but when performed with such irresistible rhythmic élan as it was here one didn’t feel inclined to complain. Tenor Filipe Manu and bass-baritone Michael Mofidian were excellent as the pining lovers, but it was mezzo-soprano Rosie Aldridge’s heart-melting rendition of Se tu m’ami (If you love me) that stole the show. IH

The EIF continues until Aug 29. Tickets and details: 0131 473 2000; eif.co.uk

Proms 2021, CBSO/Gra?inyt?-Tyla, Royal Albert Hall, London SW7 ★★★★☆

The three pieces in this rich and thought-provoking Prom all rode under the banner of “symphony”, but that was almost all they had in common. First off was the Second Symphony by Ruth Gipps, an extraordinarily gifted musician who once took on the role of oboist, conductor and composer in a single concert. The orchestra on that occasion was the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, so it seemed fitting that this performance to honour Gipps’s centenary was given by the same orchestra, under the baton of its music director Mirga Gra?inyt?-Tyla who, during her tenure, has proved a real champion of neglected British composers both male and female.

This symphony, which the 25-year-old Gipps composed after the end of the Second World War, traced her emotional journey through the previous traumatic years. The piece began in a spirit of pre-war innocence, the music often in the shadow of Vaughan Williams’s pastoral idiom but with a distinct harmonic restiveness.

It was not so much a contemplation of nature as a vigorous walk through it, as if new heart-expanding vistas were constantly appearing over the brow of a hill. The calling-up of her husband to military service and the festive departure of the soldiers to the front were all depicted with touching naivety, a quality beautifully captured in this performance. Even the slow movement portraying the lonely wartime wife had no real shadows to darken its serene pastoral lyricism.

From that heart-on-sleeve music, we passed to a new symphony that seemed devoid of all heart. Thomas Adès’s Exterminating Angel Symphony is based on his opera that was produced at the Royal Opera in 2017, in which a bunch of rich, over-sexed dinner guests are trapped in a room by some unknown force. Their personalities and feelings are weirdly distorted as a result, a process mirrored in Adès’s sly twistings of musical idioms that in their original guise were packed with genuine feeling: a Ravel-flavoured waltz, a lullaby, an agonisingly slow descent in the strings where a ghost of some other composer was evoked, possible Sibelius.

Adès proved once again he is the master of “shock and awe” in music; here a glistening, silvery bit of harmonic magic, there a sudden obliterating, ear-shredding explosion topped with shrieking piccolo. By the end it felt as if my feelings had been relentlessly worked over by a brilliant and somewhat sadistic rhetorician, who thinks stunning his audience is the same thing as moving them.

Does it really need to be said that the final piece, the Third Symphony by Johannes Brahms (a composer Adès famously despises) left the other two in the shade? Perhaps it does, in an era when musical judgement is apt to be swayed by ideology and special pleading. As always, Mirga Gra?inyt?-Tyla cast a well-known piece in an interesting new light, making this taut, tumultuous symphony seem mysteriously intimate and spacious. Even when the interpretation didn’t convince, it certainly stirred one’s emotional life. After the previous piece, that felt like healing balm. IH

Hear or watch this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Proms 2021, BBC Phil/Gernon, Royal Albert Hall, London SW7 ★★★☆☆

The best-laid human plans can be overturned by a mere microbe, as we are reminded every day. Already the Proms schedule, so carefully put together to tiptoe round quarantine and travel regulations, has been disrupted. On Tuesday night, the first of the BBC Philharmonic’s three Proms was deprived of its Israeli chief conductor, Omer Meir Wellber, and the premiere of the BBC commissioned piece from Israeli composer Elle Milch-Sheriff had to be abandoned.

Fortunately, the BBC Philharmonic’s Chief Guest Conductor Ben Gernon was able to step into the breach and lead a hastily reconceived all-Viennese programme of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Nothing wrong with that, you might say, especially with young German pianist and recent winner of a BBC New Generation Artist Award Elisabeth Brauss on hand to play Mozart’s brilliant and festive 23rd Piano Concerto.

The first piece, Haydn’s Drumroll Symphony, presents a question. Should that famous opening drumroll creep in from silence or explode like a thunderclap? Gernon went for the latter option, which is surely more authentic given that a thunderclap would have been needed to persuade an 18th-century audience to stop gossiping and pay attention.

That “authentic” beginning was appropriate for a performance which was light and fleet in what everyone takes to be the proper 18th-century manner, though for me it didn’t register the grandeur of the piece. There were nice touches such as the clarinetist’s gleeful ornamentation in the Trio, but overall the performance felt blandly efficient. Although the programme-note writer described the broad, smiling major-key melody of the variation movement as “fat”, which is a good word, this performance was definitely lo-fat. The leader Zo? Beyers’s delightful solo playing in the same movement was the best thing about the performance.

Then came that Mozart piano concerto, which passes from graceful pathos in the first movement to deep tragedy in the second. In Brauss’s performance, the first registered much better than the second. She wanted to take the slow movement to some lonely place to amplify its inconsolable quality with a sense of utter solitude. A good idea in theory, but it ignored the fact we were in the Royal Albert Hall, not some small gilded chamber in 18th-century Vienna. I doubt whether the people in the upper circle heard more than half of her tiny, silvery notes.

Some years ago, Maria Jo?o Pires proved in a solo recital that it’s possible to project to the back row of the Albert Hall and still create a sense of intimacy. Brauss is certainly gifted, and she caught the brilliance of the Finale, but has some way to go yet.

Then came Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony, and here the evening finally came to life. Not everything came off; the Trio felt rushed and as a result lost its smile. But the opening had the enticing feeling of mystery that the opening of Haydn’s symphony had lacked, and Gernon’s very fast tempo in the scherzo and the finale brought a sense of risk and excitement that elsewhere had been sadly lacking. IH

Hear or watch this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms

Proms 2021, SCO/Emelyanychev, Royal Albert Hall, London SW7 ★★★☆☆

Mozart’s last three symphonies are among music’s miracles. They have a balanced perfection that suggests the patient honing of years, but in fact they were dashed off in a few weeks in 1788.

Each has a different tone. The first of them, No. 39, is the hardest to pin down in a single phrase. It is grand and sturdy and sometimes a touch melancholy. No. 40 is the romantic and wildly tragic one. The last, known as the “Jupiter”, is in Mozart’s grand, aloof vein, with a brilliant finale that shows he could do complicated counterpoint as well as Bach.

Any of these Grecian vases makes a lofty and moving centrepiece to a concert. But is it really a good idea to play all three in a row, as the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and its young and very fresh-faced conductor Maxim Emelyanychev did at Sunday night’s Prom? There’s only so much sublimity the human frame can stand. The answer, says Emelyanychev, is yes, if your approach is to upset Mozart’s Olympian balance and poise and reveal the unruly energies lurking just underneath. That’s been his trademark ever since he burst on the musical scene some 10 years ago in his early twenties, and it’s won him many devoted fans. At times, I’ve been among them.

On Sunday evening, though, I wasn’t so sure, which isn’t to say all three symphonies didn’t have their wonderful moments. Emelyanychev has a way of making Mozart’s balanced phrases seem startlingly vivid, at first generating emphatic swells in dynamics and then retreating almost to a whisper – with just the tiniest hesitation in tempo at the close to set the next phrase in relief. He likes to do the repeats of whole sections that many conductors omit, just to give himself and the players the pleasure of doing things in a strikingly different way the second time around.

All this, together with his fleet, light tempos and the orchestra’s lively, pungent sound – authentic valveless horns and trumpets to the fore – really made one sit up and take notice. There were some entertaining moments too, such as the dialogue between the clarinet and flute in the Trio of the 39th Symphony, when the two players vied with each other in adding pert decorations to Mozart’s plain, graceful melody.

So what’s not to like, you might think? Simply that, taken as a whole, so many nervously energised tweakings started to seem over-wrought or even neurotic. And sometimes, they were actually self-defeating. It doesn’t make Mozart’s amazing, proto-modernist distortions of the melody in the finale of the 40th symphony more striking if you also distort the rhythm as well. In fact it robs that avant-garde moment of its power. These performances were a reminder that great performances aren’t made up of “striking moments”. In fact the greatest performances, like the greatest music, may have no striking moments at all. An unassuming, graceful performance won’t stop listeners (and critics) dead in their tracks, but that doesn’t mean it’s not truer to Mozart’s genius. IH

Hear or watch this Prom for 30 days via the BBC iPlayer. The Proms continue until September 11, all broadcast live on BBC Radio 3 and on the iPlayer. Tickets: 020 7070 4441; bbc.co.uk/proms