Remarkable things you probably didn't know about medieval London

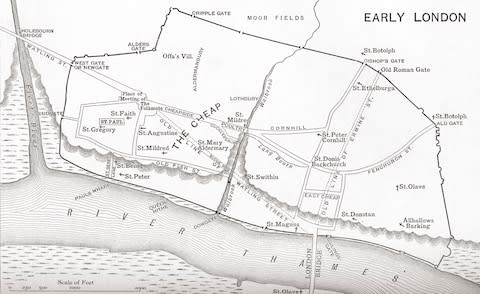

London in the Middle Ages was both fascinating and terrifying in equal measure. A deafeningly loud and increasingly crowded city crammed inside barely one square mile.

Here are a few of the most remarkable facts about medieval London – plus tips on where to find the remnants of this period in the modern capital.

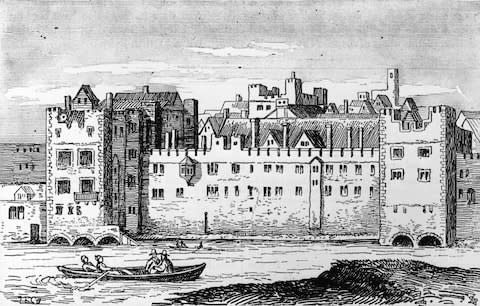

1. The Tower of London had two siblings

The Normans actually established three castles in London to help subdue the locals and keep the Vikings at bay.

Baynard’s Castle, named after the nobleman Ralph Baynard, stood where the Thames and Fleet rivers once met - close to what is now Blackfriars Tube - for more than a century. King John had it torn down in 1213, but a second property with the same name was built in the 14th century. It became a royal palace and was where both Edward IV and Mary I were crowned, but didn’t survive the Great Fire of 1666. The name lingers, however. Castle Baynard is one of the City’s 25 wards, there’s a Castle Baynard Street, and the Brutalist Baynard House is occupied by BT.

Montfichet's Tower, meanwhile, was built on Ludgate Hill, overlooking the Fleet river, a stone’s throw to the north (it was also demolished by John in 1213). These twin fortifications ran along what is now the Old Bailey road, hence the name.

2. There were rivers everywhere

There still are – but they are hidden from sight. The Fleet river, mentioned above, now reduced to a trickle in culvert, was once a significant geographical feature. It was also notoriously filthy, and filled with “the sweepings from butchers’ stalls, dung, guts and blood,” according to Jonathan Swift. Evidence of its size can still be seen. “Mysteriously steep Pentonville Rise make sense when seen as the sides of the Fleet Valley,” explains Tom Bolton, writing for Telegraph Travel. “Holborn Viaduct is a bridge with no river built on the site of an ancient Fleet crossing. The Hampstead and Highgate Ponds are former reservoirs created by damming two streams that form the Fleet.” Find out more about London’s fascinating lost rivers (there are 21 in total).

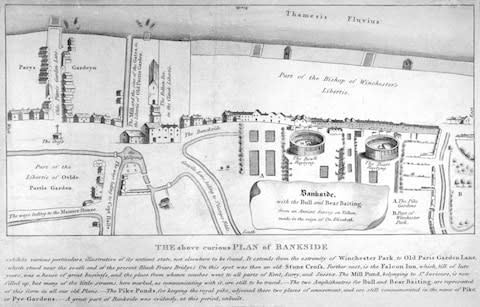

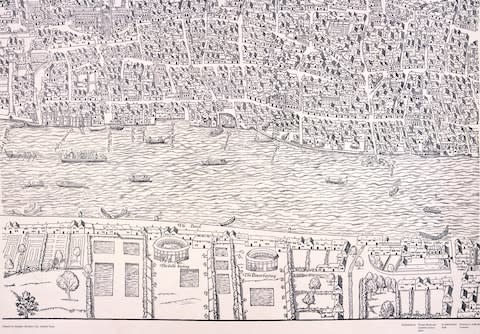

3. And bear-baiting arenas

Medieval London was a pretty grim place. In addition to the rivers filled with dung and guts, animal cruelty was considered fantastic entertainment, and the south bank was home to a pair of arenas used to bait bears and bulls (and goodness knows what else) with fighting dogs. They can be seen on a 1560 map of London. “A rude and nasty pleasure,” was Pepys’ assessment.

4. There were vineyards in the city

Londoners loved a few tankards of wine. In fact, they were rarely sober. It was imported from France, of course, but also home-grown. The Medieval Warm Period, which lasted from around 950 to 1250, made viticulture viable. Vineyards existed outside the city walls - but also within. Vintry, another of the City’s 25 wards, was once the main district for wine growing. Learn more about it all on a medieval wine tour, run by Dr Matthew Green.

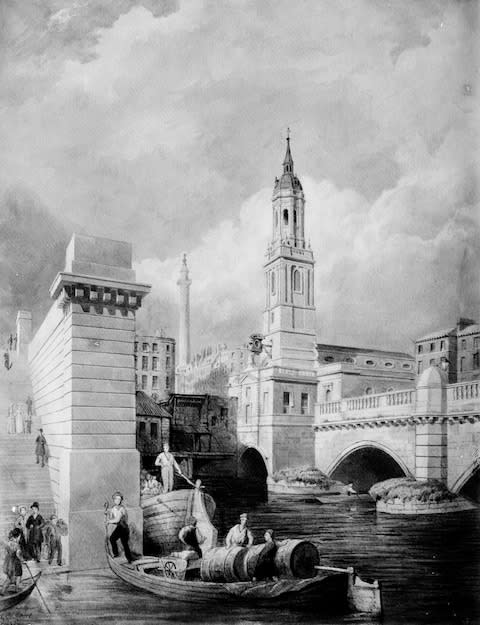

5. London Bridge was further downstream – and lined with shops

Old London Bridge, which stood from 1209 until 1831, was - for centuries - London’s only Thames crossing. Despite being just eight metres wide (compared to the modern London Bridge, which is 32 metres across) it was, by 1358, already crowded with 138 shops. By the Tudor period there were around 200 buildings on it, some seven stories high, including the palatial Nonsuch House, the earliest documented prefabricated building.

It was sited a little further east than its modern replacement, with the church of St Magnus the Martyr once overlooking its northern entrance (remnants of the old approach to the bridge can still be seen in the churchyard).

The southern gatehouse was notorious for displaying the severed heads of traitors, dipped it tar and impaled on spikes. The noggins of William Wallace and Thomas More were among those given the macabre treatment.

To glimpse something of Old London Bridge, head to Victoria Park in Hackney, where a surviving fragment has been turned into a pedestrian alcove.

6. But crossing it was a nightmare

All those shops and homes left just four metres for pedestrians and coaches to pass, which made crossing London Bridge a laborious experience. Indeed, it was usually quicker to take a water taxi. Ferrymen once lined the river offering their services. And if you look closely, there’s evidence. Not far from the Globe Theatre there’s a stone perch carved into a wall, a pint-sized alcove where a ferryman once waited for business. Where exactly? Bear Gardens, which takes its name from one of those aforementioned bear-baiting arenas.

7. The city was filthy

This isn’t exactly shocking. Environmentalism and civic duty don’t really matter when the life expectancy is 35. But London in the Middle Ages was a wondrously dirty city. The place names told the full story – there were more than a dozen Dirty Alleys, Dirty Hills and Dirty Lanes, as well as an Inkhorn Court, a Deadman’s Place and a Foul Lane.

Mount Pleasant (a street name that survives) was the tongue-in-cheek name for a medieval dumping ground, while Sherbourne Lane was formerly known at Shiteburne Lane – the street was a longtime public privy.

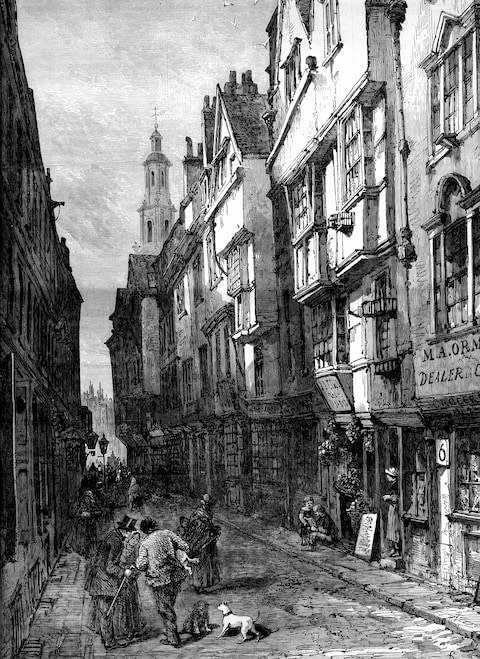

8. And noisy

So noisy, in fact, that the din could be heard from the Surrey Hills. That’s according to Peter Ackroyd’s London: The Biography. “London rang with the hammers of artisans and the cries of tradesmen and in certain quarters, like those of the smiths and the barrel-makers, the clamour was almost insupportable,” he writes. “In the early medieval city, the clatter of manufacturing trades would have been accompanied by the sound of bells, among them secular bells, church bells, convent bells, the bell of the curfew and the bell of the watchman.”

9. There was a curfew?!

Indeed. At 9pm in the summer, but earlier in winter, the bells of St Mary-le-Bow, St Martin’s, St Laurence and St Bride’s rang to signal the start of curfew. Taverns were cleared and the city’s seven gates were bolted. Anyone found roaming the streets after this time faced being arrested as a “night-walker”.

10. The Tower of London had a menagerie

King John was the first to keep wild animals at the Tower, with records showing payments made to lion keepers. Later additions to the Royal Menagerie included leopards (a gift from Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II), a polar bear (courtesy of Haakon IV of Norway), and an African elephant (thanks due to Louis IX of France). The elephant died, possibly after being given red wine.

The menagerie was opened to the public in the 18th century – admission cost three half-pence or the supply of a cat or dog to be fed to the lions.

There was also once a Royal Aviary, built in the 17th century on the southern side of St James’s Park - hence the name Birdcage Walk.

11. There wasn’t much beyond the city walls

Except for rolling hills, that is.

When Roman rule collapsed in the 5th century, the walled city was effectively abandoned. Alfred the Great is credited with “refounding” London in 886, and reviving trade and life within the old Roman boundaries. For centuries, until the Tudor period, the vast majority of London existed within this ancient fortification. Hackney, Tottenham, Islington, Chelsea, Battersea, Fulham and St Pancras, were tiny villages surrounded by unspoiled countryside.

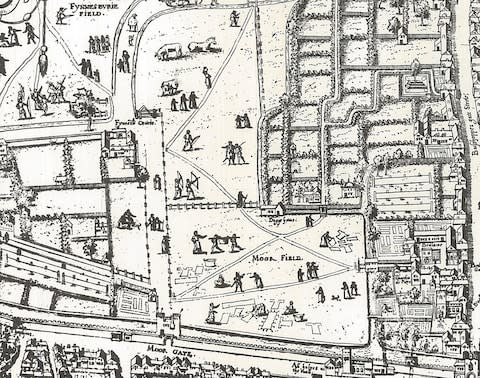

Moorfields, now in the heart of the concrete jungle, was open land. A 1560 map shows Londoners using it to dry their washing and practice their archery.

Smithfield was a grassy area known as “Smooth Field”, beyond the wall and with easy access to grazing and water (from the Fleet river) – making it a logical location for a livestock market. It remains a meat market today (though that grazing land is long gone).

12. Highgate and Hampstead were part of an immense forest

The Forest of Middlesex once stretched for 20 miles from the city walls at Houndsditch to the north. William Fitzstephen described it as a “vast forest, its copses dense with foliage concealing wild animals – stags, does, boars, and wild bulls.” Harrow Weald Common, Highgate Wood, Queen's Wood (also in Highgate) and Scratchwood (in Barnet) are among the only surviving fragments.

13. Guilds ran the show

London’s guilds controlled how trade was conducted and, to all intents and purposes, ran the city, with members appointed to influential positions in the community. Each had (and in most cases, still has) its own hall and coat of arms, and the extensive list offers an insight into the occupations available to medieval Londoners. There were guilds for bakers, cutlers, saddlers and plumbers, weavers, masons, butchers and brewers, skinners, salters, goldsmiths and barbers, fishmongers, carpenters, blacksmiths and dyers.

Modern street names still offer an inkling as to the sort of businesses once found there: Poultry, Milk Street, Cornhill, Threadneedle Street and Bread Street all hark back to the medieval period.

Then there was Guildhall, where representatives from each of the various guilds would meet. Still the administrative centre of the City of London today, Guildhall’s construction began all the way back in 1411. But this corner of London has been significant for far longer. During the Roman period, it was the site of an amphitheatre, the largest in Britain, after which it may have been the site of an earlier Anglo-Saxon Guildhall. Trials to have taken place in Guildhall include those of Lady Jane Grey, Francis Dereham and Thomas Culpeper (lovers of Catherine Howard) and Thomas Cranmer.

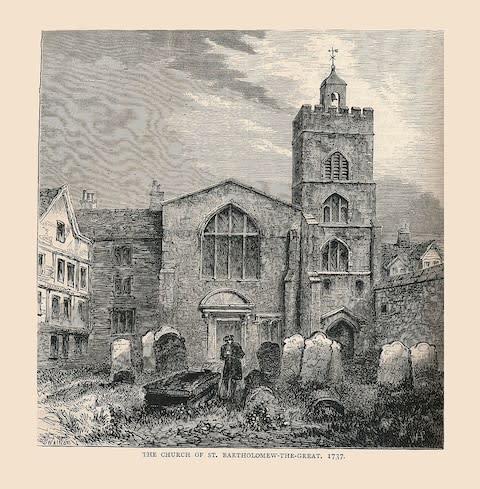

14. There were more than 100 churches inside the city walls

More than any city in Europe. In 1893’s The History of London, Walter Besant notes that “there was no street without its monastery, its convent garden, its college of priests, its friars, its pardoners, its sextons and its serving brothers”. A slight exaggeration, perhaps, but medieval London did contain more than 100 churches, seven large friaries (including Grey, White and Black), five priories, five priests’ colleges and four nunneries.

Among the few churches to have survived the Great Fire are St Giles-without-Cripplegate, St Andrew Undershaft, St Ethelburga's Bishopsgate, St Helen's Bishopsgate and St Olave Hart Street. St Bartholomew-the-Great, founded as a priory in 1123, also lives on. An extensive list of London’s many monastic houses, past and present, can be found here.

15. The Strand was where wealthy landowners lived

The road linking the city with Westminster was, suitably, where many of medieval London’s mansions were located. They backed onto the Thames (“Strand” comes from the Old English “strond”, which means “edge of a river”) and included Savoy Palace (destroyed in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381) and Arundel House. The addition of the Thames Embankment pushed the river back in the 19th century. Head to Victoria Embankment Gardens to see just how much of it was lost. York Water Gate, which was built in 1626 as York House’s entrance to the Thames, is all that survives of the mansion – but now stands some 100 metres from the water.

16. London fell to the French

The last time London was occupied by a foreign force wasn’t 1066 but actually 1216. Rebel nobles, angry with King John, invited the future Louis VIII of France to come and claim the throne. The First Barons’ War saw Louis seize much of the south-east, including London. He was welcomed by the citizens of London and proclaimed (but not crowned) king at St Paul’s Cathedral. The death of John, however, saw his support dwindle, and the following year he accepted a truce and returned to France.

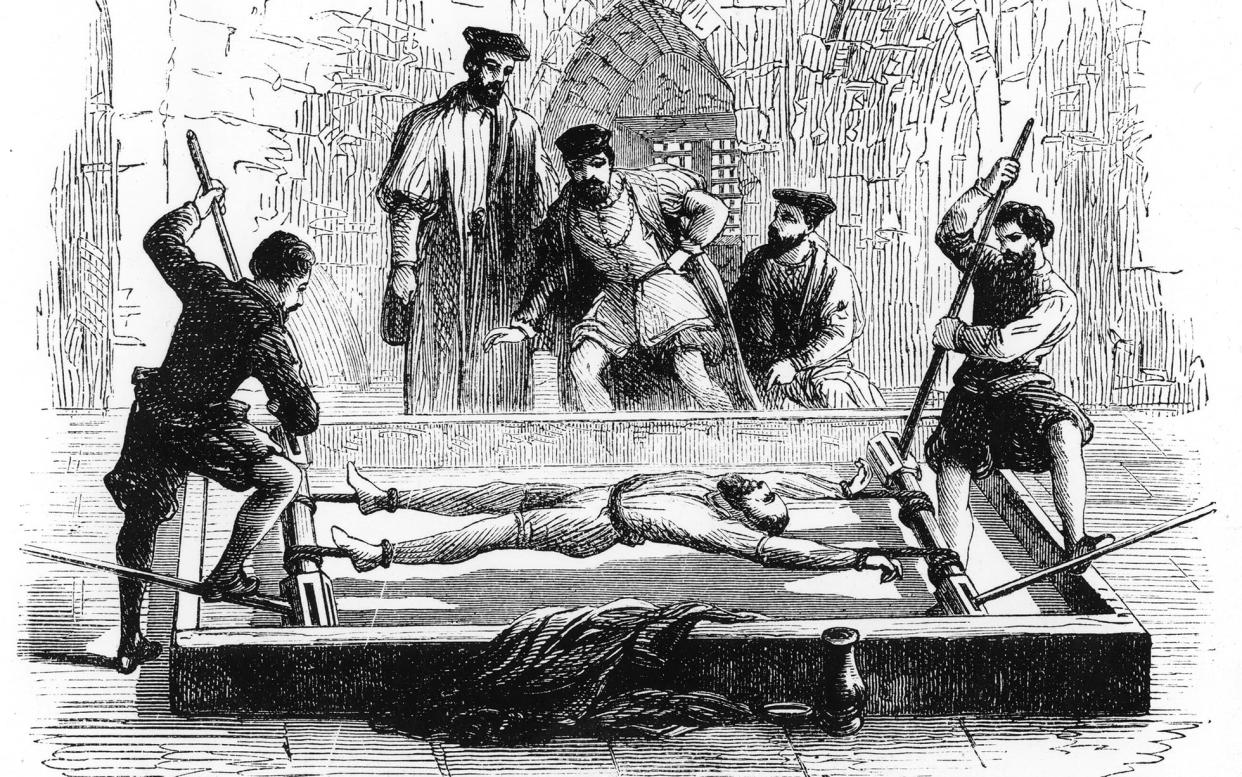

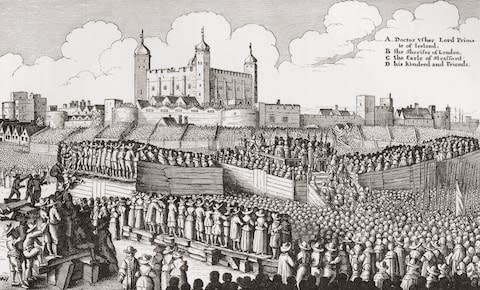

17. Public executions were rather frequent

London has a clutch of execution sites, among the most notorious being Smithfield (William Wallace), Tyburn (now close to Marble Arch, one of central London’s busiest corners), Tower Green (Anne Boleyn, Lady Jane Grey and Robert Devereux), Tower Hill (Thomas Cromwell and Sir Thomas More), Execution Dock (for pirates, smugglers and mutineers) and Kennington Common.

18. And prison life wasn’t much fun

London’s most notorious medieval jail was Newgate, whose former inmates include Casanova, William Kidd and Daniel Defoe. Ackroyd writes that “during the coroner’s inquests of 1315-16, 62 of the 85 corpses under investigation were taken from Newgate Prison. It was essentially a house of death.”

The building was gutted in 1666, rebuilt six years later and finally demolished in 1904. The Old Bailey occupies the main site, but head to the church of St Sepulchre-without-Newgate to see the old jail’s execution bell; Amen Court, which is home to a surviving wall; or The Viaduct Tavern, where five former cells of a neighbouring lock-up are visible in the basement.