How Robbie Robertson's hidden Indigenous and Jewish heritage influenced The Band's mournful songs

The word "mythic" appears in nearly every appraisal of the recently deceased Robbie Robertson's immense contribution to popular music. As the New York Times phrased it in the announcement of his death Wednesday, "The chief composer and lead guitarist for The Band offered a rustic vision of America that seemed at once mythic and authentic." Robertson's music with The Band, featuring Levon Helm on drums and vocals, poured the foundation for the construction of the genre with the awkward name Americana. Everyone from Bob Dylan, who briefly employed The Band as his backup group, to Lucinda Williams cites The Band as essential to their musical formation. Robertson was Canadian, and yet his exploration of America's diverse musical terrain – rock and roll, gospel, blues, country, jazz – emerged as one of the most definitive.

The irony does not end with Robertson's Canadian origin. During his most influential years with The Band, Robertson was living his own myth. "I never talked about my heritage much," Robertson told an interviewer in 2017 while promoting the publication of his memoir "Testimony." His mother was Indigenous, having spent her childhood years on a Six Nations Reserve outside of Toronto. She told her son, "Be proud that you're an Indian, but be careful who you tell." Having spent time in a school – not a residential one, but still oppressive – that tried to "take the Indian out of the Indian," Robertson's mother was painfully aware of the threat of racism. She indicated to Robertson that outwardly expressing his Indigenous ancestry would invite hatred, harassment and eventually lead to his exclusion from institutions and networks crucial to mainstream success.

To complicate matters, Robertson would also learn that he was Jewish. His mother confessed that the man he believed was his biological father was actually his stepfather, and that his birth parent was a professional gambler who died in a hit-and-run accident. Throughout his childhood and early adulthood, Robertson suffered through, what he called, "an undertoned racism and antisemitism" – hateful remarks from people who did not know his heritage, and disrespectful "jokes" from those who did. His most beautiful memories of infancy and adolescence involved routine visits to the Six Nations Reserve with his mother. A "great joyous feeling of connection" electrified those visits, and it allowed him to observe relatives, most especially his mother, who could "enter and leave two different worlds."

Robertson largely kept these memories as secrets, acting on his mother's practical advice to never trust easily and to preemptively guard against the slings and slander of racism.

The search for home and the struggle for belonging surges through the best of The Band's music. Their most iconic song, "The Weight," depicts a wayfarer's travels through Nazareth, Pennsylvania, and makes the most of the town's eponymous replication of the city in Israel where many Biblical scholars believe Jesus Christ spent his formative years. Like Mary and Joseph seeking shelter for their child, the singer of "The Weight," whether it is Levon Helm or, in cover versions, Mavis Staples or Aretha Franklin, hopes to find relief from the weight of the world; hopes to find home.

Robertson's rollicking guitar struggles for sonic space over the Dixieland jazz of "Ophelia," The Band's broadcast of nostalgia for a home that is lost. "Ashes of Laughter / The ghost is clear / Why do the best things always disappear," Helm sings with emotive enunciation of Robertson's mournful lyrics.

Levon Helm's vocals are at their most plaintive and resonant on "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down," a now controversial song that aches with sadness and loss. It tells the story of a poor white Southerner during the last year of the Civil War. While it never glorifies slavery or secession, it exorcises a spirit of mourning. Robertson's lyrics, with Helm's soulful delivery, sketch a man whose brother died in a battle, and who questions his community's future after witnessing the wreckage of war. "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" manages to capture a universal feeling of grief. Joan Baez, Jerry Garcia, soul legend, Solomon Burke, and other progressives committed to the cause of racial justice, performed the song without pangs of contradiction. The song's universality emanates out of Robertson's placement of home – its power and destruction – at the center of its lyrical and emotional world.

"The Weight," "Ophelia" and "The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down" are three of many songs that will forever live in the annals of rock and roll history, and continue to inspire singer/songwriters, especially in the Americana genre that Robertson helped to invent. One cannot help but wonder what might have happened if Robertson ignored his mother's advice and wore his Indigenous pride on his sleeve.

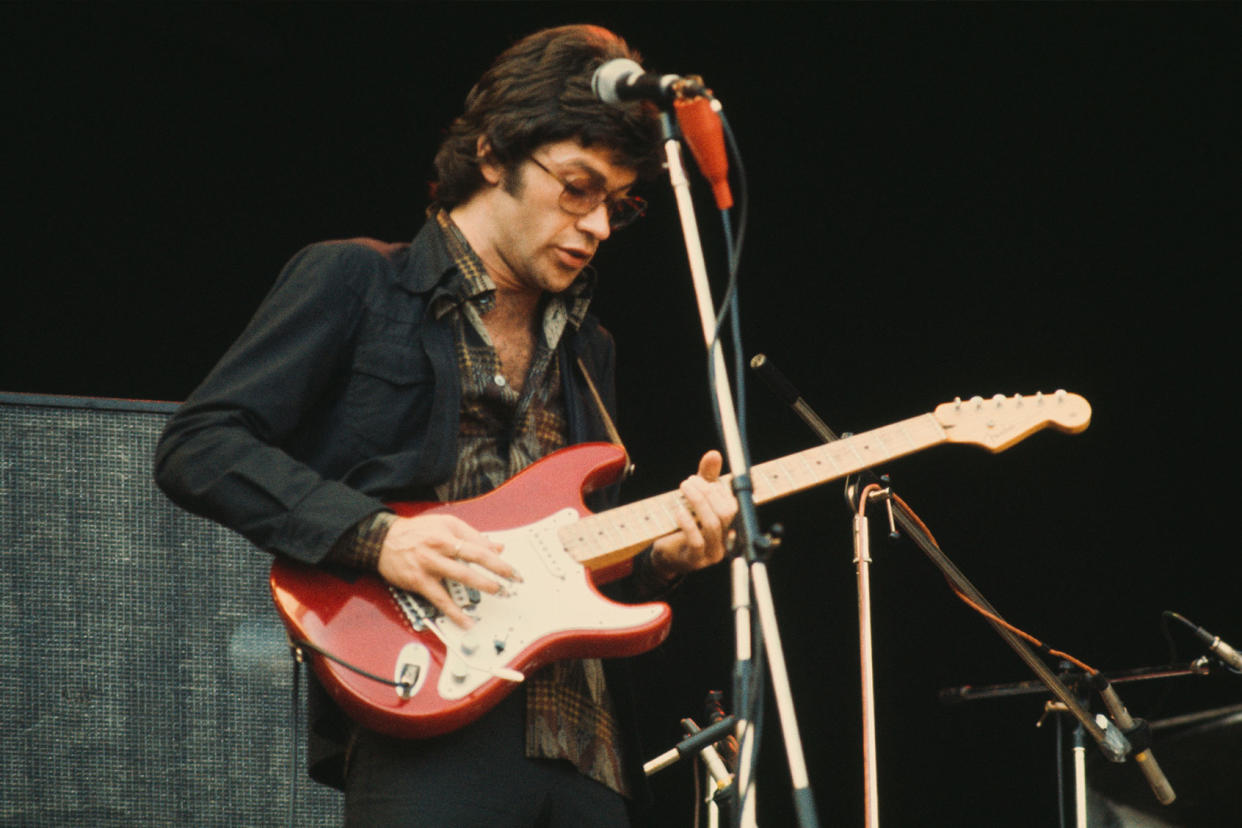

Garth Hudson, Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm, Richard Manuel and Rick Danko of The Band pose for a group portrait in June 1971 in London. (Gijsbert Hanekroot/Redferns/Getty Images)

The 1960s and '70s all-Native band, Redbone, did not produce music as brilliant as The Band, but they were talented musicians with an ear for a hit melody, as they demonstrated with the successful single, "Come and Get Your Love." In 1973, they released as a single, "We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee," a protest song depicting the massacre of Lakota Sioux Indians in 1890. It was a hit in Europe, but failed to chart in the US. Many radio stations banned the song from the airwaves.

Given the severity of racism and antisemitism in the 1960s and '70s, it is likely that if Robertson wrote songs like "We Were All Wounded at Wounded Knee," he would not have anywhere near the success or influence that has led to every major publication paying tribute to his undeniable artistry after his death. Many of the ongoing conversations about representation in popular culture that provoke whines of so-called woke tyranny from right-wing propagandists neglect to acknowledge the repression pervasive throughout major industries only a few decades ago. Mothers advised their children to conceal their Indigenous heritage, LGBTQ artists often had no choice but to remain in the closet for fear of bankruptcy, and Black, Asian and Latino artists had to proceed with caution so as not to seem "too Black," "too Asian," or "too Latino." The actor Martin Sheen regrets taking the career advice of managers, agents, and publicists who convinced him to drop his "too ethnic" birthname, Rámon Antonio Gerardo Estévez.

Robbie Robertson, in song and eventually in activism, did not know how to remain silent.

In 1987, Robertson released his first solo record. Robertson explains that without the considerations of The Band to take into account, and with the realization that he had to "say something knew," he decided to write and sing about his history, and the history of his people. The song that closes the album "Testimony" sounds like an like enraged rendition of Peter Gabriel's "Sledgehammer." With gospel joy, a horn section and a raucous assembly of backup vocalists, including Bono, Robertson announces that he is ready to "bear witness," shouting that he has learned that "you have nothing to lose but your chains."

The songs that precede "Testimony" amplify protest against the injustices in Indigenous history. "Testimony," in that respect, is conclusive, but it also functions as a declarative preview. In 1994, Robertson would release, as soundtrack for a documentary history about Native history, "Music for The Native Americans." "Ghost Dance" mourns the genocide of Native people and the near extinction of bison, while "It is a Good Day to Die" celebrates Indigenous resistance, from the warriors of the 19th Century to the American Indian Movement of the 1970s. The soundscape of the record hovers between the past and the present. Robertson manages to deftly weave synthesizers, modern production techniques and rock and roll guitar with traditional Native instruments, chants and melodies – creating a musical representation of the ancestors he loved during his youth; those he described as entering one world and exiting another.

Robertson's musical experimentation and politics grew more radical on his next record, 1998's "Contact from the Underworld Redboy." The title derives its inspiration from a slur that bullies screamed at him as a child. A mesmerizing record, "Contract" advances the modern and traditional fusion Robertson began to cultivate on "Music for The Native Americans." At its core is electronica, and the rock guitar is only ornamental. Robertson sampled Native chants, interviews with Indigenous leaders and even the words of Leonard Peltier, an American Indian Movement leader who is in prison for the murder of an FBI Agent, but whom many legal scholars and Native activists believe is innocent.

A 2018 survey from The Reclaiming Native Truth project found that 40 percent of respondents believed that Indigenous people no longer exist. Echo Hawk, a consultant to the project, decried the results as illustrative of the dangers associated with "lack of representation." Reclaiming Native Truth also ridicules the tendency to treat Native peoples as dinosaurs – some species that once roamed the Earth, but no longer lives in the modern world. For decades, the only pop cultural examples of Natives were in stereotyping Westerns. Unlike contemporary television, with programs like "Reservation Dogs" and "Dark Winds," in earlier eras of entertainment, it was rare to see a Native character not riding a horse. Robertson's music paying tribute to Indigenous history and life made brilliant use of cutting-edge musical technique to place the Native struggle at the heart of modern society.

In the records that followed, up to and including 2019's "Semantic," Robertson continued to perform songs that honored and navigated Indigenous tradition, culture and spirituality.

Taking his testimony into libraries and classrooms, Robertson wrote a children's book in 2015, with illustrator David Shannon, "Hiawatha and the Peacemaker." The book tells the story of how the five Iroquois Nations of what would become known as North America laid down their arms, and made peace after many years of war. They not only found unity, but developed a system of governance that functioned as an inspirational model for Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson and the other Constitutional framers of the United States. "The Great Law will be more powerful than any man," Robertson writes, quoting The Peacemaker. His words would eventually echo in the voice of John Adams who envisioned the United States as having a "government of laws, not men."

Written with a profound, but accessible sense of poetry, Robertson measures the emotional and historical depth and significance of Iroquois peace treaty, and the aspiration for justice that succeeded before the arrival of white settlers and colonialists. "Peace, power, and righteousness shall become the new way," Robertson quotes The Peacemaker as proclaiming not once, but three times in his children's book. It is worth nothing that the story in Robertson's book is exactly the kind of history under assault in Florida, Texas, Tennessee and other states with Republican leadership.

During his own life, Robertson activated a promise of peace and righteousness beyond the arts, making contributions to the Indigenous struggle for water rights, return of land, and access to higher education through the American Indian College Fund.

Want a daily wrap-up of all the news and commentary Salon has to offer? Subscribe to our morning newsletter, Crash Course.

As explanatory of his coming into consciousness, Robertson would often quote his late friend, the radical Indigenous poet and activist, John Trudell. "Here we have people that the old world doesn't exist anymore — they've done everything in their power to kill the old world so they've taken that 90 percent away and got rid of it," Trudell told Robertson when reflecting on trauma among Native people, "Then you've got this people they don't fit into the new world and in some cases you're just not welcome. So here we have these people lost between two worlds."

Acting on his mother's advice to keep his Indigenous identity quiet, Robertson found success in the new world, but never lost his soulful and political affinity for the old world. Obsessed with the search for home, he made music, whether with The Band or as a solo artist, that improvised a map for vagabonds without a precise set of directions. He found his sanctuary in songs, spirits and poetry – in the sounds and words that haunt the mysterious in-between. His music acts as a tour for anyone who would like to visit.

Read more

about this topic